Category: All About Guns

The 1853 Enfield rifle-musket is thought to be the first modern infantry rifle and was one of the most influential guns of all time.

The venerable Pattern 1853 (P-53) Enfield is familiar to every Civil War reenactor, every shooting devotee of the Indian Mutiny of 1857, and every historian or novelist who dwelt in the bloody confines—mentally, at least—of that infamous conflict.

The 1853 Enfield rifle-musket was used by troops on both sides in the Civil War and was the most-used firearm after the .58 Springfield. Author Brett Gibbons believes the P-53 was the first modern infantry rifle, and it was, without question, one of the most influential guns of all time. Its range and accuracy irrevocably changed infantry tactics and the very way in which battles are fought. It not only changed the training required for infantrymen, but also altered society’s perception of the common soldier.

Contrary to folklore, it did not cause the Indian Mutiny, but it certainly provided the spark and a convenient excuse to avoid explaining the far deeper and more complicated reasons. The spark was not the rifle but its paper cartridge and, more specifically, the lubricant (grease) used to soften the blackpowder fouling.

The story of the P-53, its paper cartridge, and their joint influence on the course of history, ballistics, ammunition manufacturing and testing, rifle design, development and testing, infantry tactics and training, and, ultimately, military strategy is too vast and multifaceted to even attempt an explanation here.

Gibbons is one of those individuals to whom we should all be grateful. From all appearances, he has devoted his life to the study of the P-53 Enfield and its ammunition, and he has written it all down and published it in four books. These are The Destroying Angel, The English Cartridge, Fire and Powder, and a rewrite, in modern English, of the British manual of musketry from 1859. They cover, in order, the advent of the rifle-musket on the world’s battlefields in the 1850s, then a close study (and how-to manual) on the paper cartridge, and finally the making of (and how to make your own) blackpowder to emulate, if not quite duplicate, the superb gunpowder available in Britain through the late 1800s.

All four can be had for a little more than $30, and if you have any interest in any of the above subjects, you will never spend a better $30. They are available from his website at www.PaperCartridges.com.

Gibbons tells his stories exceedingly well and has certainly convinced me that the P-53 was the first modern infantry rifle. Other writers maintain it was among the last of the “old” infantry rifles—muzzleloaders were replaced by breechloaders by the late 1860s—and chronologically, this is certainly true.

When you read the full story, however, it becomes obvious that the final step to the self-contained metallic cartridge, loaded from the breech, was more the ultimate piece of the puzzle than it was a ballistic epiphany. In fact, the P-53 became Britain’s first service-issue breechloader (the Snider-Enfield conversion) and one man—Col. Edward Mounier Boxer—was pivotal to both.

Gibbons begins the story with the Battle of Balaclava, in which the famous “Thin Red Line” of the 93rd Highlanders repulsed a Russian cavalry attack. Granted, they did so with the P-53’s predecessor, the Model 1851, but it established the value of aimed rifle fire at 600 yards with rifles in the hands of carefully trained infantrymen.

For Americans, the greatest interest in the P-53 is its use by soldiers on both sides during the Civil War. Recent historians, studying every imaginable aspect of that conflict, have concluded that far from being horrific death-dealers, the rifle-muskets used had little or no impact on various battles and have been overrated. As Gibbons points out, however, this failure—if it can be called that—was a result of the soldiers not having sufficient training to really put the rifle-muskets to use.

After reading and studying all this information for more than 60 years, for the first time since I initially began trying to concoct my own gunpowder at the age of 10, I feel like I have at least an inkling of how it all works.

Better late, one supposes, than never.

What I call a good pattern

One mighty nice looking Ruger #1 Grumpy

One mighty nice looking Ruger #1 Grumpy

Heavily armed Ladies NSFW

Ya’ll stand something up and salute!

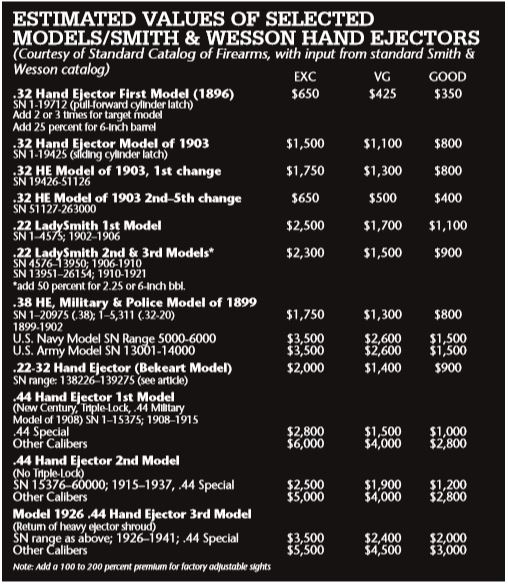

Introduced more than a century ago, the basic design of the Smith & Wesson hand ejector continues to define double-action pistols today.

What You Need To Know About Smith & Wesson Hand Ejector Revolvers:

- The first hand ejector model was the .32 Hand Ejector Model of 1896.

- Soon to follow was S&W’s first K-frame revolver—the .38 Military Model 1899 or .38 Hand Ejector Military & Police.

- The first Triple-Lock was .44 Hand Ejector First Model (New Century, Triple-Lock, .44 Military Model of 1908).

- For many, this hand-ejector model is considered to be the finest double-action pistol ever made.

Among the many contributions Smith & Wesson has given to the firearms industry, the most significant would have to be the Hand Ejector revolver. This series of solid-frame, double-action models with swing-out cylinders and manual case extraction has certainly stood the test of time. Introduced in 1896, its basic design is still in production, not only by Smith & Wesson, but also by many other gun manufacturers around the world. Author Jim Supica wrote in Standard Catalog of Smith & Wesson, “The Hand Ejector is the style of handgun that epitomizes Smith & Wesson.”

The focus of this column is on Hand Ejector models of the pre-World War II years with “Hand Ejector” in their official names. When referring to the basic design, all Smith & Wesson revolvers made since 1899 can be described as “hand ejectors,” but my plan here is to provide a bit of history on the original named models.

Toward the end of the 19th century, Smith & Wesson began work on a new-style revolver—one with a solid frame that would soon replace the popular top-break models the company had been known for since the 1870s. “Hand Ejector” is a reference to the loading and unloading procedure, whereby the shooter releases the cylinder to tilt out of the left side of the gun. This allows the cylinder to be loaded or for the fired cases to be “hand-ejected” by pushing back on the ejector rod.

Background: The .32 Hand Ejector

The first revolver to be given the name was the .32 Hand Ejector Model of 1896, its year of introduction. It was made on a new frame size called the I-frame, which had been designed for a new cartridge, the .32 S&W Long. Smith & Wesson lengthened the case of the .32 S&W by 1/8 inch to increase its powder capacity, and this required a slightly larger frame.

The Model of 1896—which would later be known as the .32 Hand Ejector First Model—was made for only seven years. It was not a big success on the civilian market, but a few major police departments, including Philadelphia’s, adopted the model as a service revolver.1

In 1903, the Second Model was introduced, along with several design improvements. The .32 Hand Ejector Model of 1903 remained in production until 1917, with a series of five changes over that time period.2 These differences were relatively minor for the first four model changes, with somewhat more significant variations internally with the fifth change.

The K-Frame Revolver

Another major contribution to firearms history from Smith & Wesson occurred in 1899 with the introduction of the first K-frame revolver—the .38 Military Model 1899 or .38 Hand Ejector Military & Police. K-frame models are still being made and are now well into their second century. They remain very popular; more K-frames have been manufactured than all other Smith & Wesson revolvers combined.3

At the same time the .38 Hand Ejector of 1899 was introduced, the most popular revolver cartridge of the 20th century, the .38 Special—or, to be precise, the .38 S&W Special—was introduced. Two of the most popular variants of this model with collectors are the U.S. Army and U.S. Navy models. These are marked “U.S. Army/Model 1899” or “U.S.N.” One thousand of each were made in 1900 and 1901.

The .32-20 was a popular cartridge in the late-19th and early-20th centuries and was another .32-caliber Hand Ejector. It went through six changes as the .32 Hand Ejector Model of 1902 and then, the Model of 1905.

The last variant remained in production until 1940. It was also made on the K-frame and could be considered the predecessor of one of the rarest Smith & Wesson models: the K-32 Hand Ejector First Model (K-32 Target). Chambered for the .32 S&W Long, only about 94 were made throughout the 1936–1941 period leading up to the beginning of World War II. Its rarity makes this version of the K-32 one of the priciest S&W collectibles.

The .22s

Several of the early Hand Ejectors were .22s. The first of these was the .22 Hand Ejector (LadySmith). Made on the tiny M-frame, it had a seven-shot cylinder and was chambered for the .22 S&W cartridge (which was the same as the .22 Long). It was in production from 1902 through 1921, with three model changes and serial number ranges.

Smith & Wesson resurrected the name, written “LadySmith,” in 1990 for a 9mm semi-auto and later for a J-frame .38 Special, which is still in the catalog.

The Bekeart Model

The .22-32 Hand Ejector had an interesting beginning. A San Francisco gun dealer named Philip Bekeart came up with the idea for Smith & Wesson to build on the .32 Hand Ejector I-frame a .22-caliber model with a 6-inch barrel and adjustable sights. He believed in the concept so much that he placed a special order in 1911 for 1,000 of these revolvers. These guns became known as Bekeart models and are highly collectible. Only 292 of the first 1,000 guns were delivered to Bekeart, and some went to other dealers. It was 1915 before Smith & Wesson put the model into regular production.

Bekeart models were not marked, so identifying them can be confusing. Serial numbers were included in the range of those for the .32 Hand Ejector (from 138226–139275), but there was a special and separate series of serial numbers stamped on the buttstock of the first 3,000, beginning with the letter “I.”4 Some collectors consider any .22-32 Hand Ejector with a letter showing shipment to Bekeart’s gun shop to be a Bekeart model. This revolver remained in production until 1941.

The N Size

The largest frame for Smith & Wesson revolvers for nearly 100 years was the N size. It was designed for a new cartridge, the .44 Special, and came aboard the S&W train in 1908. Based on a lengthened .44 Russian case, the .44 S&W Special could hold three more grains of black powder under a round-nosed, 246-grain lead bullet.5 (Some .44 Special fans might disagree with the statement that the cartridge was originally loaded with black powder, but six-gun guru John Taffin says so in Gun Digest Book of the .44.)

More Gun Collecting Info:

- The Walther PP Series

- The Quintessential 22 Pistol: The Colt Woodsman

- The Rocky History Of The L.C. Smith

- The Browning SA-22

- Colt Python: The Cadillac Of Revolvers

The Triple-Lock

The complete name of this revolver was quite a mouthful: .44 Hand Ejector First Model (New Century, Triple-Lock, .44 Military Model of 1908). Buried in the name is a feature that referred to the lockup of the cylinder; this feature became one of the nicknames of the model: the Triple-Lock. It was also often called the New Century.

In the Gun Digest Book of the .44, Taffin describes it as “the epitome of double-action six-guns: The New Century, alias the .44 Hand Ejector First Model, which would forever be known to its loyal followers as the Triple-Lock … In addition to enlarging the frame, two other improvements were made. A shroud was added to the bottom of the barrel to enclose the ejector rod, thus not only protecting the ejector rod, but also improving the looks of the S&W revolver. The second, unfortunately short-lived, improvement was the addition of a third lock, giving the Triple-Lock its unofficial name. Before, the .44 Hand Ejector First Model S&W cylinders locked only at the rear of the cylinder and at the front of the ejector rod. On the New Century, a third lock was brilliantly machined in the front of the frame at the yoke and barrel junction to solidly lock the cylinder in place.”

Interestingly, the Triple-Lock was in production only seven years. Apparently, in 1915, someone at Smith & Wesson decided that the third lock was too expensive to manufacture, and it was eliminated—as was the shroud around the ejector rod. Following the changes, the price of the revolver was reduced from $21 to $19.

About 15,375 Triple-Locks were made before the changes took place; most, but not all, were .44 Specials. A limited number was chambered in .38-40, .44-40, .445 Colt and .455 Mark II.

The .44 Hand Ejector Second Model—as it was now known—was made from 1915 to 1917, when wartime work called a halt to large-frame revolver production. The model returned to the S&W line in December 1920 and remained there until 1940.

The Third Model

Another popular .44 Hand Ejector model, called the Third Model or the Model of 1926, was added in that year. It was identical to the Second Model except for the return of the ejector rod shroud. Smith & Wesson received a large number of inquiries asking for the heavier barrel lug—many from law enforcement agencies wanting a slightly heavier revolver. The Third Model was a special-order gun until July 1940, when it was listed in the Smith & Wesson catalog shortly before it was discontinued. It was reintroduced in 1946, following the war.6

For more historical and technical information on these great revolvers, the books listed below in the footnotes are excellent sources.

FOOTNOTES

1, 6: History of Smith & Wesson, Roy G. Jinks, Beinfeld Publishing, 1977

2, 4: Standard Catalog of Smith & Wesson, Jim Supica and Richard Nahas, Gun Digest Books, 2004

3, 5: Gun Digest Book of the .44, John Taffin, 2006