Category: All About Guns

Australian Owen on Full Auto

The young lance corporal tucked the wood stock and clenched the pistol grip of his Lewis gun, a “light” machine gun he was all too familiar with from his time lugging one around during the First World War. His assistant gunner secured a magazine on top of the gun and gave his shoulder a quick tap, indicating he is loaded and ready to fire.

To the right and left of him, his fellow soldiers did the same with their Lewis guns. The anticipation was building, his heart began beating faster and faster. He felt anxious, but not like he did in the trenches during the war. This was a feeling of familiarity without the risk or sense of danger.

Someone off to the side of the firing line yelled, “Targets spotted, open fire!”. He pulled the trigger, the bolt closed, and the first round from his machine gun went off, producing a rhythmic symphony of automatic weapons fire. In the distance, several hundred meters ahead of him, the lance corporal could see his target plain as day: emus. A nice-sized group of them numbering 50 or more were scrambling across the Campion, Western Australia plains to avoid the snapping and whizzing of bullets being thrown at them at the cyclic rate.

Eventually, the mob of emu scattered, and the soldiers ceased-fire with no birds in sight to engage with their guns. As the lance corporal’s assistant gunner moved to replace the empty mag of his machine gun, he thought, I can’t believe we’re here to shoot emus. Nevertheless, his unit, the Seventh Heavy Battery, Royal Australian Artillery, spent the next month doing just that between November and December 1932.

The events described above may sound like a story someone’s grandfather fabricated to tell their grandkids. Still, one of the strangest chapters in history saw Australian troops deployed to Western Australia to assist local farmers with an overwhelming emu population.

Most have come to know this as the Emu Wars, but in 1932, it was simply a growing and aggravating nuisance to the farmers of Campion, Western Australia. Farmers already struggling to make ends meet after the rippling effects of The Great Depression now faced the threat of giant flightless birds ravaging their crops.

So, what were the results of this unique military action?

The answer may surprise some, but even with the abilities of a technologically advanced and far superior force, the deployment to quell the emu horde resulted in a failure.

For a month, the Army patrolled the countryside looking for emu, even enlisting the help of locals to lure them towards patiently waiting machine gun crews. But after the expenditure of nearly 10,000 rounds of ammunition, the military action only managed to produce roughly 950 dead emus—a dent compared to the estimated 20,000 thought to be out roaming Western Australia.

With the results of their actions seeing no significant improvement, the Army eventually left. It would appear that the Emu War was lost for the moment, giving those flightless birds free rein over farmers’ crops.

And with the Army gone, farmers still demanded the government develop a solution for emus and the destruction of their crops. Unfortunately, no such answer or solution would come immediately; however, years later, the government issued a paid bounty on emus that allowed farmers and locals to deal with the birds on their terms. The results proved very successful, with more than 50,000 emu bounties collected in less than half a year, thus bringing a triumphant end to the Emu Wars.

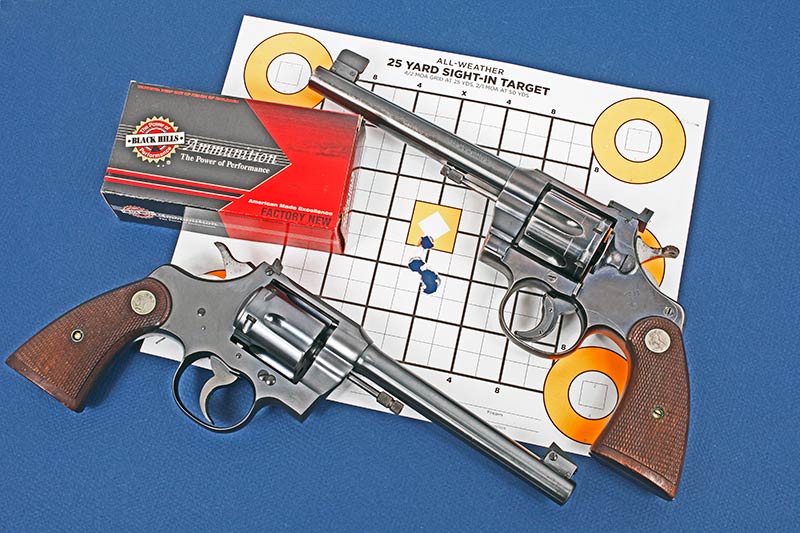

I sort of stumbled onto this .38 Special Colt Officers Model a couple of years ago. I did a favor for a friend and he asked if I wanted “Something in a box or some money?” Knowing this friend, I said, “Something in a box.” I chose wisely, as they say. The “something” I received is, from what I can discover, a “Third Issue” Officer’s Model Target, Heavy Barrel. The serial number range shows it was made in 1937 and it’s in great condition, well-used, but it times right and looks good. This was a target shooter’s gun for sure and shows honestly worn grips and back-strap blue wear typical of the sort.

The interesting bits are the front and rear sight changes, trigger shoe and hammer mod. At first, I thought it might be the work of Kings, who was the go-to source for target revolver work in those heady days of fierce firing line competition. But Kings always stamped their work and there was nary a Kings mark on this gun.

The front sight base is stock, so I think whoever did the sights installed a higher front blade to match the period-correct Micro adjustable rear. The hammer mod is that classic King design called the “Cockeyed Hammer” spur. There’s a bit of welded-on metal to the left side of the spur, then it was checkered and drilled to lighten it. It made single action cocking faster and easier, which was what was done in those days.

The SA pull is a feathery 1 lb. 10 oz. while the DA pull seems pretty stock. Accuracy is amazing, and using standard high quality 148-gr. target wadcutters from Federal and Black Hills the gun shoots 1″ at 25 yards pretty easily if I use my “good” glasses. I’ve never fired anything else through it and don’t plan on it. This is timeless, old-school cool stuff and it’s fun to re-live the 1930s.

Another Score

Then, talk about great luck, I was nosing around on a good friend’s site where he sells some amazing classic guns (www.sportsmanslegacy.com) and stumbled onto another Officer’s. This one is a Colt Officer’s Model, but factory stock — and in .22 LR! A quick serial number check revealed it began life in 1938 so I’d call it a peer to the .38. An interesting side note is the SA trigger shows 3 lbs. 10 oz. and that’s about right for dead-stock.

There’s a bit of magic at work here too. I have a blued Python and a blued Diamond Back in .22, so how on earth could I not have the parents to my more “modern” guns at-hand too? My charge card was glowing for a short time.

Smarter people than me know way more about these guns, but from what I gleaned, Colt introduced the first of these “medium-framed” models in 1904, calling it the Officer’s Model, catering to police business. Between then and about 1969, Colt produced several variations, with slightly different mechanicals and looks, but all based on the same idea of a medium-framed gun good for target shooting and even police duty use.

The Officer’s Model Target was offered beginning in about 1927 and was chambered in .22 LR, .32 Colt and .38 Special. The heavy barrel (like my .38) was made optional in about 1935. According to one source, only the 6″ barrel was offered post-war. The grips were checkered walnut with silver-colored medallions so mine seem to be correct.

In those days target shooting was pretty mainstream and these models ruled the roost. Guys like Fitzgerald of Colt honed these actions to within an inch of their lives, helping to assure the guns shot as well as humanly possible with the technology available then. As times changed, model designations changed from “E” frames (with the firing pin in the hammer) to “I” frames if the firing pin was in the frame, but the quest for quality always remained.

Living History

These guns were considered at the top of Colt’s revolver lines during their production years, and from the glass-hard, smooth actions on mine, I can see why. The stunning Colt Royal Blue — especially on the .22 here — needs no introduction. Yeah, I know, today’s guns are cheaper, “better” built, easier to make, offer more design options and run the gamut from simple to complex.

But when talented labor was cheap and hand-work the norm, the Officer’s Models were artistic mechanical marvels. They didn’t “need” to polish them the way they did, nor take the time to apply that ocean-depth blue or tune the actions so finely it’s hard not to shed a tear when you press the trigger. But they did, and the only reason for it is the pride and satisfaction of doing something 100 percent right. Not 98, or even 99.9 — but 100 percent right.

Look at the photos of the early guns here and you’ll clearly see the legacy the Python, Diamondback and even the Trooper proudly wear. Once introduced in the middle 1950s, the Python stole the show from the Officer’s Model and grabbed the top-dog, “Super Premium” slot. And rightfully so. But still, like a classic fine car, elegance of build quality, old-school design touches and that difficult to define aura all hold sway. A Python is significant — but an Officer’s Model is like a vintage Bentley, still drawing looks and compliments from everyone wherever it “proceeds.”

I put these sorts of guns in the “Fewer But Finer” pile. I’ve been selling off the “commodity” or more common guns I simply don’t use any longer and reinvesting the money in “nicer” guns. It’s a nice change of pace and at a seasoned age, it’s great fun to be able to shoot guns I only dreamt about when I was younger. You should think about all this too.