Category: All About Guns

When the United States Armed Forces entered World War I, they quickly recognized that their small arms inventory was grossly inadequate for a prolonged conflict. Six years prior to America’s entry into the war, the military had adopted the Colt 1911 pistol as the official sidearm.

Unfortunately, the amount produced did not come close to meeting the demands of the day. Even as more 1911s rolled off the line, the military sought other solutions.

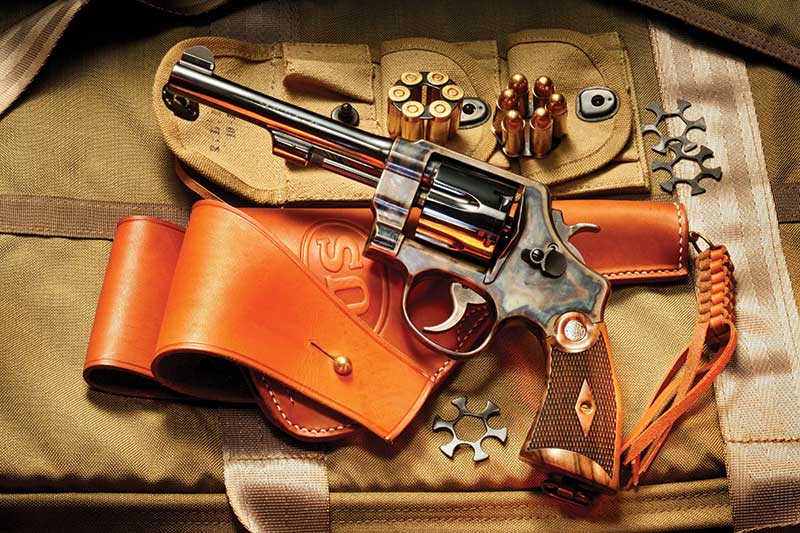

To help meet this deficit, both Colt and Smith & Wesson turned out large-frame revolvers modified to chamber the .45ACP. Colt mated the .45ACP to their New Service revolver while Smith contributed the Hand Ejector 1917. Combined, these firms produced over 300,000 revolvers for the war effort.

To help meet this deficit, both Colt and Smith & Wesson turned out large-frame revolvers modified to chamber the .45ACP. Colt mated the .45ACP to their New Service revolver while Smith contributed the Hand Ejector 1917. Combined, these firms produced over 300,000 revolvers for the war effort.

Never give it up…even then.

Never underestimate the 38 Special

Guns & Horses

When I was a kid growing up in southwest New Mexico, I was required to exercise my old pony every evening after school, which I didn’t really consider a chore, though the palomino tended to be a little salty at times. When I was old enough, my dad started letting me pack a handgun while on horseback, though he was a little nervous about it at first.

Choosing a horseback pistol isn’t something to be taken lightly, even when you’re a kid, but one thing was clear to me–it had to be a Colt. What cowboy wouldn’t be carrying a Colt Single Action while on horseback? My first choice was the first handgun I’d ever acquired, a Colt .22 New Frontier with its handmade Garret Allen holster. This outfit was perfect for knocking around the brush, especially on horseback.

My dad was a firm believer that one should never shoot from the saddle. He said it was always best to dismount and fire for a number of reasons, one of the most important being the fact that you can definitely hold your gun–handgun or rifle–much steadier. It’s also safer, especially if your horse isn’t trained to be shot off of. Nothing is more hazardous than being bucked off your horse with a loaded firearm in your hand, especially if it’s cocked. Of course, these theories had to be tested, I surmised. Just being lectured on such things wasn’t sufficient.

My old palomino, Skokie Joe, loved to buck, and I spent a lot of time hitting the ground. Shooting from that treacherous equine’s back proved to be an even more risky proposition. Fortunately, the first time I tried it I didn’t have time to recock the .22 before I hit the ground. I decided to take the old man’s advice and start dismounting to shoot, hoping the palomino would eventually get used to it. He didn’t.

I’d read a few cowboy yarns about training horses to be comfortable around guns, but most of them involved having the rider fire a high-powered rifle over the top of the horse’s head, deafening them. This method didn’t seem feasible to me at all, but it did give me an idea.

I figured if I shot a heavier caliber revolver around him enough, the .22 might seem puny to him after a while and I would be able to shoot it without incident. One afternoon I slipped out with my .45 Colt SAA on my hip, saddled Skokie Joe, and rode out several miles from the house to warm him up.

I dismounted, spotted a likely target in a mesquite thicket, and fired the Colt with one hand, holding the reins in the other. The shot caused Skokie Joe to leap into the air backwards with me in tow. He hit the ground on his hind quarters and rolled away from me. The first thing on my mind was how I was going to explain to my dad how I’d managed to bung up the bluing on my good single action.

Skokie Joe then stumbled to his feet, jerked his head, and snapped the reins. He held his head up, snorted mightily, and broke into a dead run as if a grizzly was after him.

I had plenty of time to wipe the dust off the Colt on the long walk back to our place and to think about my horse-training skills. When I finally got to the house, Skokie Joe was grazing happily in my dad’s garden, stomping down corn stalks. I was at least glad to see he hadn’t dragged my saddle off someplace.

My shooting lessons with Skokie Joe took place long before I’d ever heard of the sport of cowboy mounted shooting. I’m not sure when the sport actually started, but I’ve been interested in it for some time, though I’ve never been a participant. A few years back I did make the acquaintance of Rick Levin who was an accomplished horeseman and quite involved in the sport. He got a kick out of my stories about Skokie Joe and invited me down to Lajitas, Texsa, to demonstrate to me just how easy it was to train a horse to get used to gunfire. I was eager to learn about the right way of doing it and took him up on the offer.

Levin saddled a big bay horse that had never been around shooting and led him into the arena. In the center of the arena was a bucket of sweet feed sitting on a small table. Levin was carrying a Ruger .22 Single-Six loaded with blanks, and he began trotting the bay in a circle around the table.

He did so for five minutes or so before drawing the Ruger and firing over the bay’s hindquarters. While the bay’s reaction to the shot was nothing like Skokie Joe’s had been when I touched off my .45 years before, he still jumped and ran sideways. Levin regained control and spurred the bay straight to the table and grain bucket where his wife fed the bay a handful of the sweet grain.

This process was repeated for roughly 20 minutes, at which time the shots became more frequent and closer to the bay’s head. After about 45 minutes of the shooting/grain treatment, the bay didn’t seem to pay much attention to the shots at all.

The following day, the .22 was replaced with a .38 Special with blanks, which obviously provided a sharper report. The process was repeated, with excellent results, and the training quickly excelled to the .45 Long Colt. I understand the bay horse soon became an excellent cowboy mounted shooting competitor. Levin’s method was fascinating and simple. I’m told that this was a variation of the old U.S. Cavalry method of training horses.

I suppose had I read that old Cavalry training manual, I might have saved a lot of bruises–and a few long walks home.