Category: All About Guns

Charge (warfare)

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Charge | |

|---|---|

Romanticized painting of O’Higgins‘ charge at the Battle of Rancagua during the Chilean War of Independence

|

|

| Era | Prehistoric – Modern |

| Battlespace | Land |

| Weapons | Lances, Pikes, Swords, Bayonets, Rifles, Knives |

| Type | Maneuver warfare, Offensive warfare |

| Strategy | Offensive |

A charge is a maneuver in battle in which combatants advance towards their enemy at their best speed in an attempt to engage in close combat. The charge is the dominant shock attack and has been the key tactic and decisive moment of many battles throughout history. Modern charges usually involve small groups against individual positions (such as a bunker) instead of large groups of combatants charging another group or a fortifiedline.

Contents

[hide]

Infantry charges[edit]

Ancient charges[edit]

It may be assumed that the charge was practiced in prehistoric warfare, but clear evidence only comes with later literate societies. The tactics of the classical Greek phalanx included an ordered approach march, with a final charge to contact.[1]

Highland charge[edit]

In response to the introduction of firearms, Irish and Scottish troops at the end of the 16th century developed a tactic that combined a volley of musketry with a rapid close to close combat using swords. Initially successful, it was countered by effective discipline and the development of defensive bayonet tactics.[2]

Bayonet charge[edit]

Greek infantry charge with the bayonet during the Greco-Turkish War of 1897

The development of the bayonet in the late 17th century led to the bayonet charge becoming the main infantry charge tactic through the 19th century and into the 20th. As early as the 19th century, tactical scholars were already noting that most bayonet charges did not result in close combat. Instead, one side usually fled before actual bayonet fighting ensued. The act of fixing bayonets has been held to be primarily connected to morale, the making of a clear signal to friend and foe of a willingness to kill at close quarters.[3]

Cavalry charges[edit]

The shock value of a charge attack has been especially exploited in cavalry tactics, both of armored knights and lighter mounted troops of both earlier and later eras. Historians such as John Keeganhave shown that when correctly prepared against (such as by improvising fortifications) and, especially, by standing firm in face of the onslaught, cavalry charges often failed against infantry, with horses refusing to gallop into the dense mass of enemies,[4] or the charging unit itself breaking up. However, when cavalry charges succeeded, it was usually due to the defending formation breaking up (often in fear) and scattering, to be hunted down by the enemy.[5] It must be noted, though, that while it was not recommended for a cavalry charge to continue against unbroken infantry, charges were still a viable danger to heavy infantry. Parthian lancers were noted to require significantly dense formations of Roman legionaries to stop, and Frankish knights were reported to be even harder to stop, if the writing of Anna Komnene is to be believed. However, only highly trained horses would voluntarily charge dense, unbroken enemy formations directly, and in order to be effective, a strong formation would have to be kept – such strong formations being the result of efficient training. Heavy cavalry lacking even a single part of this combination – composed of high morale, excellent training, quality equipment, individual prowess, and collective discipline of both the warrior and the mount – would suffer in a charge against unbroken heavy infantry, and only the very best heavy cavalrymen (e.g., knights and cataphracts) throughout history would own these in regards to their era and terrain.

European Middle Ages[edit]

The cavalry charge was a significant tactic in the Middle Ages. Although cavalry had charged before, a combination of the adoption of a frame saddle secured in place by a breast-band, stirrups and the technique of couching the lance under the arm delivered a hitherto unachievable ability to utilise the momentum of the horse and rider. These developments began in the 7th century but were not combined to full effect until the 11th century.[6] The Battle of Dyrrhachium (1081) was an early instance of the familiar medieval cavalry charge; recorded to have a devastating effect by both Norman and Byzantine chroniclers. By the time of the First Crusade in the 1090s, the cavalry charge was being employed widely by European armies.[7]

However, from the dawn of the Hundred Years’ War onward, the use of professional pikemen and longbowmen with high morale and functional tactics meant that a knight would have to be cautious in a cavalry charge. Men wielding either pikeor halberd in formation, with high morale, could stave off all but the best cavalry charges, whilst English longbowmen could unleash a torrent of arrows capable of wreaking havoc, though not necessarily a massacre, upon the heads of heavy infantry and cavalry in unsuitable terrain. It became increasingly common for knights to dismount and fight as elite heavy infantry, although some continued to stay mounted throughout combat. The use of cavalry for flanking manoeuvres became more useful, although some interpretations of the knightly ideal often led to reckless, undisciplined charges.

Cavalry could still charge dense heavy infantry formations head-on if the cavalrymen had a combination of certain traits. They had a high chance of success if they were in a formation, collectively disciplined, highly skilled, and equipped with the best arms and armour, as well as mounted upon horses trained to endure the physical and mental stresses of such charges. However, the majority of cavalry personnel lacked at least one of these traits, particularly discipline, formations, and horses trained for head-on charges. Thus, the use of the head-on cavalry charge declined, although the fierce Polish hussars, French Cuirassiers, and Spanish and Portuguese conquistadores were still capable of succeeding in such charges, often due to their possession of the previously mentioned combination of the traits required for success in such endeavours.

Twentieth century[edit]

In the twentieth century, the cavalry charge was seldom used, though it enjoyed sporadic and occasional success.

In what was called the “last true cavalry charge“, elements of the 7th Cavalry Regiment of the United States attacked Villista forces in the Battle of Guerrero on 29 March 1916. The battle was a victory for the Americans, occurring in desert terrain, at the Mexican town of Vicente Guerrero, Chihuahua.[8][9][10][11]

One of the most successful offensive cavalry charges of the 20th century was not conducted by cavalry at all, but rather by mounted infantry, when on 31 October 1917, the Australian 4th Light Horse Brigade charged across two miles of open terrain in the face of Ottoman artillery and machine gun fire to successfully capture Beersheba in what would come to be known as the Battle of Beersheba.

On 16 May 1919, during the Third Anglo-Afghan War, the 1st King’s Dragoon Guards made the last recorded charge by a British horsed cavalry regiment[12] at Dakka, a village in Afghan territory, north west of the Khyber Pass.[13]

During the Spanish Civil War, there was a massive cavalry charge by the Fascist’s division during the Battle of Alfambraon 5 February 1938, the last great mounted charge in Western Europe.[14]

Several attempted charges were made in World War II. The Polish cavalry, in spite of being primarily trained to operate as rapid infantry and being better armed than regular Polish infantry (more anti—tank weapons and armored vehicles per capita) did execute up to 15 cavalry charges during the Invasion of Poland. Majority of the charges were successful and none was meant as a charge against armored vehicles. Some of the charges were mutual charges by the Polish and German cavalry such as Battle of Krasnobród (1939) and one time, the German cavalry scouts from 4th Light Division (Germany) charge against Polish infantry from 10th Motorized Cavalry Brigade (Poland) was countered by Polish tankettes moving from concealed positions at Zakliczyn. On Nov. 17, 1941, during the Battle of Moscow, the Soviet 44th ‘Mongolian’ Cavalry Division charged the German lines near Musino, west of the capital. The mounted Soviets were ravaged by German artillery, then by machine guns. The charge failed, and the Germans said they killed 2,000 cavalrymen without a single loss to themselves.[15] On 24 August 1942, the defensive charge of the Savoia Cavalleria at Izbushensky against Russian lines near the Don River was successful. British and American cavalry units also made similar cavalry charges during World War II. (See 26th Cavalry Regiment). The last successful cavalry charge, during World War II, was executed during the Battle of Schoenfeld. The Polish cavalry, fighting on the Soviet side, overwhelmed the German artillery position and allowed for infantry and tanks to charge into the city. The cavalry suffered only 7 dead, while 26 Polish tankmen and 124 infantrymen as well as around 500 German soldiers ended up dead.[16][17][18])

After World War II, the cavalry charge was clearly outdated and was no longer employed[citation needed]; this, however, did not stop modern troops from utilising horses for transport, and in countries with mounted police, similar (albeit unarmed) techniques to the cavalry charge are sometimes employed to fend off rioters and large crowds.

Impact of firearms[edit]

In the firearms age, the basic parameters are speed of advance against rate (or effectiveness) of fire. If the attackers advance at a more rapid rate than the defenders can kill or disable them then the attackers will reach the defenders (though not necessarily without being greatly weakened in numbers). There are many modifiers to this simple comparison – timing, covering fire, organization, formation and terrain, among others. A failed charge may leave the would-be attackers vulnerable to a counter-charge.

There has been a constant rise in an army’s rate of fire for the last 700 years or so, but while massed charges have been successfully broken they have also been victorious. It is only since the late 19th century that straight charges have become less successful, especially since the introduction of the machine gun and breech-loading artillery. They are often still useful on a far smaller scale in confined areas where the enemy’s firepower cannot be brought to bear.

Notable charges[edit]

Charge of the Light Brigade, Painting by Richard Caton Woodville

Richard Caton Woodville, Poniatowski‘s Last Charge at Leipzig

- Battle of Gaugamela (October 1, 331 BC) 1,800 Greco-Macedonian Companion cavalry, led by Alexander the Great himself and supported by brigades of hypaspists and part of his phalanx, charged and broke through the center of a huge Achaemenid army of more than 50,000 warriors led by Darius III, the emperor.

- Battle of Hastings (October 14, 1066): 2000 Norman heavy cavalry repeatedly charged uphill at several times their number in Anglo-Saxon infantry, who had formed a shield wall. All charges were repulsed until the Saxon infantry, thinking the Normans were retreating, broke their formation to follow them and were routed by the Norman cavalry.

- Battle of Dyrrhachium (October 18, 1081): 1,300 Norman cavalry under Robert Guiscard, Duke of Apulia, were initially repulsed by the Varangian Guard. The Varangian Guard were in turn routed by a counterattack to their flanks by Norman infantry, fled to the sanctuary of a nearby church which the Norman forces burnt down. The Norman knights then charged the Byzantine line again, and caused a widespread rout. First recorded instance of a successful and decisive ‘shock’ cavalry charge.

- Battle of Falkirk (July 22, 1298) The English cavalry without orders from the king charged and though able to break Scottish archers and cavalry, was unable to break the tight formation of Scottish pikemen deployed in schiltrons. King Edward I withdrew his knights back and used his longbowmen to weaken and break up the Scottish lines. The English knights rejoined the battle under cover of the arrow fire and routed the Scottish infantry with heavy losses.

- Battle of the Golden Spurs (July 11, 1302): The French cavalry, consisting of many nobles was defeated in battle by heavily armed Flemish militiamen on foot. The cavalry charge was cited to be rash and premature with the battlefield’s many ditches and marshes blamed for the loss, and at a few points on the Flemish line the French horsemen did manage to break through before being surrounded and annihilated. However it also demonstrated that well-disciplined and heavily armed infantry could defeat cavalry charges, ending the perception that heavy cavalry was practically invincible against infantry.

Together with the Battle of Bannockburn (below), the battle contributed to the end of the perception of cavalry supremacy in warfare.

- Battle of Bannockburn (23–24 June 1314) The mounted English knights under Edward II charged the Scottish lines without covering arrow fire were slaughtered by the Scottish pikemen. Also in the same battle, the Scottish cavalry charged and routed the English-Welsh archers.

- Battle of Crécy (August 26, 1346): 29,000 French and allied troops charged 16,000 English soldiers on a gentle slope. Under heavy longbow fire, the charge was a total disaster, with the French army losing over 1500 knights, many of them from important noble families.

- Battle of Poitiers (19 September 1356): Unlike the other major battles of the Hundred Years’ War, the French knights and men-at-arms attacked the English lines on foot in fear of what happened in Crecy. However, instead this led up to the English knights and men-at-arms to mount up and charge. The combined attack of longbowmen and cavalry charge defeated the French army.

- Battle of Agincourt (October 25, 1415): Dismounted French knights become bogged down in a charge against the outnumbered English forces. The charge was slowed and stalled by the thick mud of the Agincourt field, allowing the light English infantry to kill and capture many French knights and prominent French nobles.

- Battle of Patay (June 18, 1429): French heavy cavalry managed to catch a retreating English army by surprise, and for the first time succeeded in defeating the English longbowmen in a direct confrontation, marking a turning point in the Hundred Years’ War.

- Battle of Nagashino (1575) – Charge of Takeda clan cavalry against massed arquebusiers behind stockades and supported by other infantry fails with heavy losses.

- Battle of Gembloux (January 31, 1578): 1,200 Spanish cavalry led by Alexander Farnese, charged into a Protestant army 25,000 men strong. After the first clash with the enemy cavalry, the Spanish cavalrymen assaulted the infantry, resulting in 6,000 killed and the total destruction of the Protestant army.

- Battle of Kircholm (September 27, 1605) – Polish cavalry 2,600 men supported with 1,000 infantry defeated 11,000 Swedes. Polish-Lithuanian winged hussars charged and completely defeated advancing Swedes.

- Battle of Klushino (4 July 1610) – Polish forces numbering about 4,000 men (of which about 80 percent were the famous ‘winged’ Polish hussars[19] under Hetman Stanisław Żółkiewski defeated a numerically superior force of about 35,000–40,000 Russians under Dmitry Shuisky, Andrew Golitsyn and Danilo Mezetski. In battle many formations of hussar units charged 8 – 10 times.

- Battle of Vienna (September 11–12, 1683): 20,000 Polish, Austrian and German cavalry led by the Polish king Jan III Sobieski and spearheaded by 3000 heavily armed Polish hussars charged the Ottoman lines. This is the largest cavalry charge in history[citation needed].

- Battle of Eylau (February 8, 1807): 11,000 French cavalry under Joachim Murat charge the centre of the Russian army to save the French army of Napoleon.

Somosierra, by January Suchodolski, 1860

- Battle of Somosierra (November 30, 1808): During the Peninsular WarNapoleon overwhelmed the Spanish positions in a combined arms attack, charging the Polish uhlans or Chevau-légers of the Imperial Guard at the Spanish guns while French infantry advanced up the slopes. The victory removed the last obstacle barring the road to Madrid, which fell several days later.

- Battle of Salamanca (July 22, 1812) Described as probably the most destructive charge made by a single brigade of cavalry in the whole Napoleonic period, Major General John Le Marchant‘s heavy cavalry brigade (5th Dragoon Guards, 3rd and 4th Dragoons) destroyed battalion after battalion of French infantry.

- Battle of Borodino (September 7, 1812) Three cavalry corps containing French, German and Polish regiments struck the enemy’s centre. The Russian cavalry counter charged and this led to a general cavalry battle.

- Battle of Dresden (August 27, 1813) French cavalry under Marshal Murat succeeded in cutting off and annihilating the Allies’ left wing. Several Austrian infantry divisions were caught in the open with inoperable muskets (due to heavy rains) by the French combination of cavalry and horse artillery and thus suffered heavy casualties, many soldiers surrendering. Napoleon’s forces achieved a great victory.

- Battle of Waterloo (June 18, 1815): Two brigades (about 2,000 men) of the British heavy cavalry charged and annihilated the advancing French infantry (14,000 men) on the left flank of the Allied army. Later during the battle, the French cavalry mounted an attack with 9,000 men on the Allied infantry positions in the centre, but were unable to break the infantry’s squares.

- Charge of the Light Brigade (October 25, 1854) at the Battle of Balaclava in the Crimean War. Due to faulty orders a tiny force of 670 British light cavalrymen charged an enemy force many times their size. They succeeded in breaking through as well as disengaging, but suffered extremely heavy casualties and achieved no important objectives.

- Battle of Gettysburg (July 2, 1863) After running out of ammunition, Col. Joshua Chamberlain ordered the 20th Maine Volunteer Infantry Regiment to fix bayonets and charge down the hill at the 15th Regiment Alabama Infantry. Shocked by the movement, the Confederates ran down the hill. After the charge, the 20th Maine had captured most of the 15th Alabama. 262 soldiers of the 1st Minnesota Volunteer Infantry regiment charged a Confederate infantry unit in order to gain five minutes of time for the army of the Potomac. During the charge the regiment suffered 82 percent casualties. After the charge only 40 men were left, making it the worst single loss of any unit in the American Civil War.

- Pickett’s Charge (July 3, 1863) at the Battle of Gettysburg in the American Civil War. Mass infantry assault on the Union lines but was bloodily repulsed by Union forces.

- Third Battle of Winchester (September 19, 1864): the largest cavalry charge of the American Civil War.

- Battle of Franklin (1864) (November 30, 1864): the largest infantry charge of the American Civil War.

- Battle of the Little Bighorn (June 25–26, 1876) General George Armstrong Custer leads at least 268 men of the 7th Cavalry Regiment against 900 – 1800 Lakota and was annihilated

- Battle of Wörth (August 6, 1870): French heavy cavalry brigade, with two squadrons of light cavalry, charges Prussian infantry in the village of Morsbronn, lost 800 men and the battle.

- Battle of Mars-la-Tour (August 16, 1870): “Von Bredow’s Death Ride”. Prussian heavy cavalry brigade overrun French infantry and artillery to reinforce left flank of Prussian Army, at cost of half the brigade. One of the few notable examples of successful cavalry charges after the introduction of modern firearms.

- Charge of the 21st Lancers in the Battle of Omdurman, September 2, 1898: 400 British cavalry charge 2,500 Mahdistinfantry. This was also one of the first battles Winston Churchill engaged in, and was accurately described in his first book, The River War.

- Relief of Kimberley (13 February 1900): Major-General John French led a charge of 7500 cavalry through Boer lines to lift the Siege of Kimberley during the Second Boer War.

Charge of the Australian 4th Light Horse Brigade at the Battle of Beersheba.

- Prunaru Charge (November 28, 1916):

- Charge of the 4th Light Horse in the Battle of Beersheba (October 31, 1917): two regiments of Australian Light Horse charge an unknown number of entrenched Turkish infantry and Austrian artillery.

- Charge of the 7th Dragoon Guards, November 11, 1918: British cavalry make an opportunistic charge on German infantry to capture Lessinesand the Dender crossings in Belgium. The last cavalry charge of World War I, with the action completed as the clocks were striking 11 o’clock to mark the end of hostilities.[20][21]

Charge of Polish hussars at the Battle of Klushino 1610

- Battle of Komarów (August 31, 1920): a vital and decisive battle of the Polish–Soviet War. It was the largest and last great cavalry battle of significance in which cavalry was used as such and not as mounted infantry.

- The last British army’s cavalry charge by a complete regiment was executed in Turkey during the 1920 Chanak Crisis, when the 20th Hussars successfully charged a body of Turkish infantry.[22]

- Charge at Krojanty (September 1, 1939): a cavalry charge that gave birth to the myth of Polish cavalry charging German tanks. In fact, Polish cavalry charged a regiment of German soldiers and were surprised by the arrival of a group of armored cars and retreated.

- Battle of Krasnobród September 23, 1939: last cavalry battle in Europe fought between Polish and German cavalry units (Polish victory; a German general is taken as prisoner of war)

- Battle of Bataan (January 16, 1942): the 26th Cavalry Regiment of the United States makes a mounted pistol charge against Japanese positions, the last mounted charge in battle by conventional United States troops.

- Charge of the Savoia Cavalleria at Isbuscenskij, (August 24, 1942): the last cavalry charge of Italian history against a regular enemy formation. It was mounted against a Soviet artillery position along the River Don by 700 men of the 3rd Cavalry Division Eugenio di Savoia. This is often reported as “the last successful cavalry charge in history”.[23]

- Battle of Poloj (October 17, 1942): The last charge of an Italian horse regiment during WWII. It was executed in Yugoslavia by the 14th Light Cavalry Regiment “Cavalleggeri di Alessandria” versus Communist partisans.

- Battle of Schoenfeld was the last charge of the Polish 1st Cavalry Brigade just before the end of WWII. On March 1, 1945, it attacked the German lines in support of Soviet forces. The charge was successful.[24]

- Korean War (February 7, 1951): A company of soldiers from the U.S. Army’s 27th Infantry Regiment launched an infantry charge that successfully defeated an enemy machine gun position.

- Battle of Mount Tumbledown (June 13–14, 1982): British infantry charge Argentine positions in the Falklands War. The last successful British bayonet charge until 2004.[25]

- Battle of Vrbanja Bridge (May 27, 1995): the French Commandos Marine launched a bayonet charge to retake a sangar held by the Army of Republika Srpska at Suada and Olga bridge (formerly called “Vrbanja bridge”) in Sarajevo, during the Bosnian War. It was the first bayonet charge for the French since the Korean War.[26]

See also[edit]

Early in the morning of March 3, 1991, Rodney Glen King was driving a 1987 Hyundai Excel along the Foothill Freeway in the San Fernando Valley of Los Angeles. He was accompanied by his friends Freddie Helms and Bryant Allen. King and his buddies had killed the previous evening watching basketball and drinking at a friend’s house. At around 1230 in the morning, King passed Tim and Melanie Singer, a husband/wife California Highway Patrol team. The Singers initiated a pursuit, eventually reaching speeds of 117 mph. King refused to pull over.

King later admitted that he knew a DUI charge would violate his parole and send him back to prison. 2.5 years earlier King had robbed a Korean grocery store while armed with an iron bar. He assaulted the store owner and made off with $200 cash. King was eventually apprehended, tried, and convicted. He served one year of a two-year sentence before being released.

King departed the freeway and led the cops on a merry chase through residential neighborhoods at high speeds. The pursuit eventually involved multiple police units from different agencies as well as a police helicopter. After some eight miles the officers finally cornered King and stopped his car.

King’s two companions were removed from the vehicle and arrested albeit with some violence. Freddie Helms was later treated for a laceration to his head. For his part, King purportedly giggled and waved at the orbiting helicopter. The senior LAPD officer onsite took charge and directed the LAPD contingent to swarm King for a takedown.

Up until this point the cops were clearly in the right. However, everybody involved was energized. The arresting officers beat King mercilessly and tased him at least once. Medical personnel later documented a right ankle fracture, a crushed facial bone, and sundry contusions and lacerations. King’s Blood Alcohol Content indeed showed him to have been legally intoxicated. His tox screen was also positive for marijuana. Without the knowledge of the police, a local plumbing salesman named George Holliday shot a video of the brutal beating. This footage eventually made it into the media.

The story behind the Holliday footage is simply fascinating. The opening biker bar scene from Terminator 2: Judgment Day was being filmed just across the street from where the cops finally stopped King’s Hyundai. Holliday actually had his video camera set up in hopes of catching a glimpse of Arnold Schwarzenegger.

During a subsequent interview he said, “Before the beating, right across the street from where we lived was a biker bar, and they were filming Terminator 2: Judgment Day there. I actually have footage on the original tape of Schwarzenegger getting on the bike and riding off.” Had they not been filming the movie, Holliday would not have had his video camera in position and ready.

Thirteen days later, 15-year-old Latasha Harlins entered Empire Liquor in Los Angeles and put a $1.79 bottle of orange juice in her backpack. Soon Ja Du, a Korean-American woman who owned the establishment along with her husband, confronted her about it. Du claimed that Harlins denied having the juice. Two young witnesses disputed that claim, asserting that Harlins had the money for the juice in her hand and was planning to pay for it.

Latasha Harlins was the product of some of the most sordid stuff. Her father regularly beat her mother until they eventually separated. When Latasha was nine years old her father’s new girlfriend shot and killed her mother in a dispute outside an LA nightclub. The poor girl was subsequently raised by her maternal grandmother.

Harlins and Du got into a shouting and shoving match, and Du ended up on the floor. As Harlins turned to leave, Du retrieved a revolver from behind the counter and shot the girl once in the back of the head, killing her instantly. Though she was convicted of voluntary manslaughter, Du was only sentenced to five years’ probation, a ten-year suspended prison sentence, 400 hours of community service, and a $500 fine. The sentencing judge stated that the fact that Du had been robbed multiple times before affected her actions and mitigated her culpability.

The four police officers who beat Rodney King were subsequently tried and acquitted. Film director John Singleton was in the crowd outside the courthouse when the news was announced and stated, “By having this verdict, what these people done, they lit the fuse to a bomb.” His words were prescient.

The Riots

The synergistic combination of Rodney King’s vicious videotaped beating, the acquittal of the officers involved, and Soon Ja Du’s mild sentence in the killing of Latasha Harlins precipitated a hurricane of violence. Riots began the day after the verdict was announced. Soon much of LA was in flames.

64 people died in the violence, and another 2,383 were injured. 3,600 fires were set and 1,100 buildings were immolated. Fire calls came into dispatchers at a rate of one per minute for a time. First responders were utterly overwhelmed.

The government invoked a dusk-to-dawn curfew and mobilized the California National Guard along with Federal Law Enforcement and some active-duty military personnel. The violence continued for six days. Property damage ultimately ran between $800 million and $1 billion.

One extraordinary episode demonstrated why military troops should never be used in Law Enforcement roles. When responding to a domestic violence incident a combined force of LAPD officers and US Marines closed on a Compton home. A violent criminal was holding his family hostage inside. Upon their approach, the suspect fired two shotgun rounds through the front door, injuring a police officer. One of the LAPD cops then shouted, “Cover me!”

In keeping with their training, the Marines immediately laid down a withering base of fire to cover the cop’s maneuver. In a matter of moments, they had saturated the house with some 200 rounds. Miraculously the inhabitants were unharmed. A bit shocked, I rather suspect, but nonetheless unhurt.

Rooftop Koreans

In general, Koreans were the local shop owners, while African-Americans were their customers. There was a low-grade antipathy percolating between these two ethnic groups that boiled over after the Harlins incident. As a result, rioters targeted Korean-owned businesses for destruction. Police were so overwhelmed as to be unable to respond to calls for help. Countless established family businesses were burned to the ground.

The businesses that survived were those that were adequately defended. In a violent, chaotic, lawless world, some Koreans armed themselves, retreated to their rooftops, and prepared to shoot looters. The resulting iconography created a modern legend among responsible armed Americans. The controversy surrounding those people, their actions, and those images roils even today.

The Guns

I studied all the pictures I could find to see what sorts of weapons these armed Americans were using. In 1991 California gun control laws were not quite so draconian as is the case today. For the most part, these armed Koreans wielded fairly mundane ordnance.

Standard-capacity combat handguns like Beretta 92’s, Glock 17’s, and sundry Smith and Wesson pistols were in evidence. There were numerous bolt-action hunting rifles along with sporting shotguns of various flavors. I spotted a couple of Mini-14 rifles and an AK. The most intriguing weapon I could find was a Daewoo Precision Industries K2.

The K2 is currently the standard service rifle of the South Korean military. Development began in 1972 and spanned a variety of prototypes in two different calibers. The definitive 5.56mm version was first fielded in 1985.

The resulting weapon reflected the state of the art. A gas piston-driven design based upon the proven Kalashnikov action, the K2 fed from STANAG magazines and featured a 1-in-7.3 inch, 6-groove barrel. GI weapons included safe, semi, 3-round burst, and full auto functions. Small numbers of semiauto variants were briefly imported by Kimber, Stoeger, and B-West in the 1980s. The 1989 import ban via executive order by Bush the First capped the numbers in the country and rendered the gun an instant collector’s item. From what I have seen at least one of these superlative weapons made its way onto the rooftops of these Korean-owned businesses during the LA riots.

The Rest of the Story

Rodney King was ultimately awarded a $3.8 million civil judgment and became fairly wealthy as a result. He bought a house for his mother as well as another for himself with the proceeds. Tragically, King never mastered his sobriety. In 2012 he fell into his swimming pool and drowned. He had cocaine, marijuana, PCP, and alcohol in his system at the time. He was 47.

Two of the four cops involved in the beating were eventually convicted of violating King’s civil rights and spent 30 months in federal prison. All four left Law Enforcement. None of them remained in California.

Reginald Denny, a passing white truck driver, was dragged from his vehicle by an angry mob and brutally beaten. One rioter struck him in the back of the head with a cinder block, severely fracturing his skull. After extensive surgery and therapy, Denny eventually regained the capacity to walk. I guess that’s something.

Ruminations

Today the uprising is referred to as “Sa-i-gu” within the LA Korean community. This translates as “April 29,” the day the violence began. During those six horrible days, multiple warning shots were fired, but no rioters were injured or killed by the rooftop Koreans. Like all parasitic scavengers, the rioters gravitated toward the areas with the easiest pickings. Businesses bristling with armed Koreans were essentially left alone.

Modern commentary on the phenomenon of the rooftop Koreans is delightfully biased. Left-wing commentators state that the willingness of these shop owners to arm themselves in defense of their businesses was pure unfettered racism. They further assert that those of us who venerate this behavior are knuckle-dragging neanderthals awash in toxic masculinity and driven by insensate, race-based venom. I must respectfully disagree.

Speaking solely for myself, of course, I don’t care one whit what color the people were who were defending their businesses or burning them down. I tend to judge others based on their civic-mindedness and propensity toward responsible behavior. Regardless of ethnicity, I categorize those who burned down their neighborhoods as the Bad Guys and those who prevented them from doing so as the Good Guys. Failure to appreciate that obvious truth seems fairly incomprehensible to me.

There is but a thin veneer of civility that separates human animals from the lesser sort. We never seem to be more than one headline away from violence and carnage. To those who might defend the actions of the rioters, you’re all idiots. Feel free to venerate the criminals if that be your wish, but don’t act surprised when the rest of us find solace in our firearms and sense of community.

I don’t minimize the egregious nature of the Rodney King and Latasha Harlin’s tragedies. However, they both had their origins in deep societal brokenness. Until we can repair the basic family structure in these derelict communities nothing will ever get better. Guns, poverty, drugs, and violence are simply symptoms. Dysfunctional families, a dearth of responsible fathers, and a lack of positive role models is the underlying disease. It remains to be seen if anyone has the moral fortitude to stop screaming about the symptoms and conjure an effective cure.

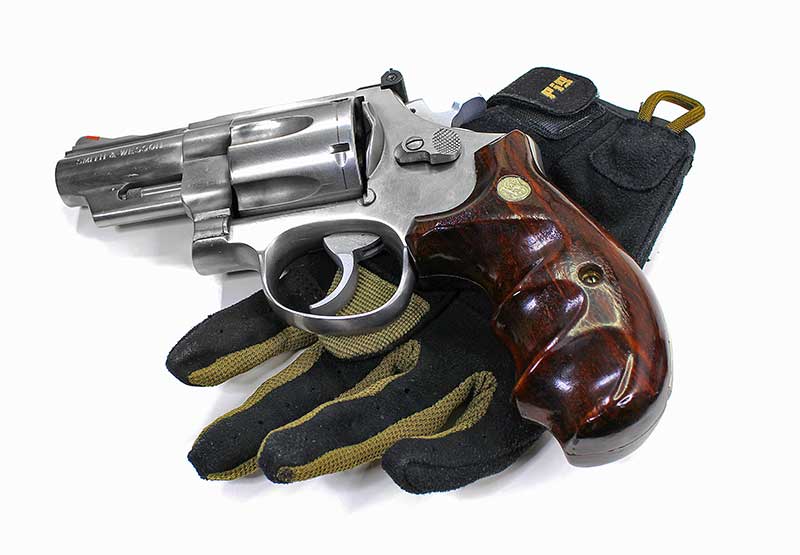

S&W 44 magnum ( The Rundown )

Best Guns for Wild Hogs

There’s a reason why most people shoot a .22 better than a .44 Magnum. Recoil has long been the enemy of realizing the full measure of a gun’s mechanical accuracy. At my range, I’ve seen many very strong and hardy young men talk up hard-kicking handguns like the Desert Eagle and the S&W 500. I’ve also watched many of those strong, hardy young men flinch magnum rounds into the dirt.

To paraphrase George Bernard Shaw, youth is wasted on the young. Now that I’ve shot long enough to shut off my inner reptile brain, my hands are admittedly achier than they once were. (Note: being a writer has not helped this condition.) As such, I certainly find myself in the ranks of those who see the worth of a “soft shooting” handgun.

You might find yourself with a similar value system for reasons of your own. If so, you’ll likely ponder the following: What makes one handgun shoot more stoutly or softly than another? This is an answerable question and one that transcends discussions of caliber alone.

Size And Weight

It’s been a while since many of us took high school physics, but we might dimly remember that force is equal to mass times acceleration. Many of us tend to focus on “force.” We can think of this as the power of the cartridge for which any particular firearm is chambered. However, we should be equally concerned with acceleration, and by that, I mean how rapidly any given gun accelerates into your hand under recoil. Newton’s second law tells us that acceleration and mass are inversely related for any given force.

Put more simply, big guns kick less than small guns of the same caliber. This seems counter-intuitive at first: Witness the number of well-meaning husbands who buy snub-nosed revolvers for their wives. Small guns seem cute, genteel, and easy to handle. That said, show me a lady who shot a scandium J-Frame .38 as her first gun, and I’ll show you a lady who had a horrible first trip to the range — and likely never returned.

If you want to keep recoil to a minimum, extra mass is the ticket. It’s another reason why I tend to prefer barrels of 6″ on revolvers and 5″ on autoloaders: More sight radius is nice, sure, but the extra weight out at the front of the gun adds just a little “special sauce” when it comes to taming recoil.

Ergonomics

A deceptive category, to be sure! Many people buy a revolver or semi-auto because it feels “good in the hand.” That’s better than nothing, but one also wants to make sure it feels good under recoil. The platonic ideal is a gun that fits one’s hand just so, with no gaps or recesses. This will allow the firearm and hand to behave as one unit under recoil, distributing all forces evenly. When this isn’t the case, it can feel like the gun is slamming back into one’s palm.

Sometimes our own biology is at fault when it comes to amplifying the negative effects of recoil. Many big-handed dudes have been cut by the slides of Walther PPKs and bit by the beak-like hammer of a Browning Hi-Power. Even a gun with a modest “kick” can be quite painful under recoil if your hand doesn’t interface with it well.

Personally, I don’t play well with medium- and large-framed guns from a certain manufacturer. Thanks largely due to their rectangular grip frame, they tend to vector recoil right into the knuckle at the base of my thumb — no thanks, I say. Not every pistol will work for every user, as we may perceive the effects of recoil differently from one another.

Grip And Grip Material

Wooden grips on a revolver can be a thing of beauty. However, there’s a reason why Ruger ships its Super Redhawks with big, cushy rubber stocks: Metal and wooden grips have absolutely no “give.” On a heavy kicking gun, hard grips won’t make things worse, but they certainly won’t make things better. Instead, rubber grips once again help to distribute recoil over a larger part of the hand and over a longer duration of time. Those gray-pebbled rubber Hogue grips might not be someone’s first choice of shoes for a vintage S&W, but aesthetics be damned — they work.

Another interesting variable comes in the form of polymer construction. Almost as a rule, polymer frames will be lighter than those made from aluminum or steel. Based on our previous discussion of weight, one would think this would indicate they’d be harder kickers. And yet, I’ve shot some polymer guns that shoot as softly as their metal-framed brethren.

I think the phenomenon comes down once again to “flex” or “give.” Some polymer compounds can act as shock absorbers, as they can be compressed or deformed more easily than metal but will rebound to their original, molded shape. The effect is slight but not negligible!

Additionally, how one grips the gun is important. A strong grip locks the firearm into place and again aids the goal of allowing the gun, wrist, hand and arm to move as one unit. (And, as a combined mass, will therefore accelerate less under the same recoil force.) But supposing one has a weak and/or improper grip, the gun will squirm in hand and distribute recoil forces unequally. Good technique will absolutely reduce the perception of recoil.

Action And Slide Velocity

Remember our previous discussion of a force being exerted over time? Well, it also applies here, and not all guns are created equal. While exceptions exist to the rule, most autoloaders can be classified into “blowback” and “locked breech” designs.

Blowback actions are the simpler of the two. When a round is fired in a gun of this design, only the stiffness of the recoil spring and mass of the slide inhibit its rearward movement until the chamber reaches safe pressures. As the gun cycles, the slide (and only the slide) moves backward, usually at a high velocity, contributing to a “snappy” feel when it rams into the rear of the frame. Usually, this action is reserved for guns chambered in smaller calibers.

Conversely, just about any gun chambered in 9mm or larger is going to have some kind of locking mechanism. If you watch a video of a 1911 or Walther P38 in extreme slow motion, you’ll see the barrel and slide travel together for a bit before the barrel unlocks and the slide continues its rearward movement. Recoil forces act on more things, in more directions and over a longer period of time. Recoil is generally felt more like a shove than a snap.

Guns chambered for .380 ACP — of which there are a lot — can be one of the two action types. My GLOCK 42, a locked breech design, is very comfortable to shoot. My Colt 1908 is far less pleasant, thanks to its blowback action. I’d also be remiss if I didn’t note there are blowback guns in larger calibers.

Additionally, springs are a factor. For example, H&K’s USP series of handguns utilize a dual spring system, where the last bit of slide travel under recoil is further dampened by a second, stiffer recoil spring. As I understand it, H&K moved away from this design in the name of simplification — why use two parts when one will do? I see the logic, but I (and other devotees) simply love how the USP setup feels.

Also, when guns have no springs or slides, there’s little to attenuate the recoil. A single-shot handgun or revolver typically has greater recoil than an autoloader of identical size, weight and caliber.

And Egads … More?

We haven’t even begun to touch on the effect of muzzle brakes, bullet weights and velocities, slow-burning vs. fast-burning powders, torque, weight changes as magazines deplete, aftermarket parts and add-ons and the much-ballyhooed subject of bore-over-frame height. And I’m sure there are even some factors I’m forgetting.

The main takeaway is there are so many different variables and so many guns we’re rarely able to make apples-to-apples comparisons when it comes to recoil. Sure, I can tell you a 4″ gun will kick more than a 6″ gun if it’s the same make, model and caliber. Or an M&P .40 will kick more than an M&P in 9mm. However, if you were to ask me off the top of my head whether a Ruger LCR in .327 Federal kicks more than a .45 ACP-chambered 1911 stoked with +P+ ammo … who knows?

Don’t get me wrong: Keeping track of all of the above variables is certainly helpful when it comes to identifying soft shooters or hard kickers. However, the real world almost always complicates our well-crafted theories. Sometimes you just have to shoot a gun to find out how much you can tolerate the kick, push, shove, or slap it transmits when you pull the trigger.