Category: All About Guns

“The bulwark of this Volkssturm in Japan proper is the Second National Army, which in peacetime consists of a large group of untrained males of military age. With the small amount of training now being given this group and with the formal registering on its rolls of all 17- and-18-year-olds since November 1944, the use of civilians in the defense of the Japanese homeland begins to assume increasing military importance.”

—Secret U.S. Military Intelligence document from the Pacific Theater of Operations, March 1945

While the Allied concept of “unconditional surrender” of Axis forces in Europe was sound, the prospects of a national Japanese surrender seemed unlikely. Before anyone knew anything about the war-ending potential of the atomic bomb, American military planners had to prepare to overcome a fanatical defense of the Japanese home islands—a battle during which the Japanese military appeared ready to sacrifice their entire population to protect their homeland.

But while the Japanese spirit was willing, their physical resources were growing weak. The emperor’s forces struggled to provide enough firearms and ammunition to their combat troops. To train and supply a large civilian militia with effective modern small arms would require extreme ingenuity to match the traditional Japanese willingness to sacrifice. Consequently, the Japanese would develop some of the crudest firearms of World War II.

Setting The Stage For Operation Downfall

Allied leaders concluded that they could not wait for a blockade and intensive bombings to bring about a Japanese surrender—a massive invasion of the home islands was necessary. Meanwhile, a timeline was set for the defeat of Japan within one year of the surrender of Germany. The larger plan, dubbed “Operation Downfall,” was divided into two parts: Operation Olympic and Operation Coronet.

Olympic was to be the invasion of Kyūshū, scheduled for Nov. 1, 1945. Coronet was the second phase, with a massive force planned to invade Honshu in March 1946. All the main preparations were made without any knowledge of atomic bombs, and until the successful A-bomb test (July 16, 1945), it would have been folly to plan for the intervention of any secret weapon. A massive amount of brute force was the Allied recipe for success.

As American forces progressed in the island-hopping campaign, reaching islands closer to Japan proper, they encountered more Japanese civilians in the combat zone. These encounters provided a clearer picture of what Allied forces could expect when they invaded the Japanese home islands. American intelligence began to understand the scope of the Japanese militia, and the militarists plans for “The Glorious Death of One Hundred Million.”

In a March 28, 1945, Military Research bulletin, American intel resources reported on the “employment of Japanese civilians in local defense:”

“It has long been the policy of the Japanese Army, even in peacetime, to keep close check upon all Japanese males of military age, not only as to whereabouts and amount of military training received but also as to education and occupational skills. This policy has been facilitated by assigning every fit male to a reserve component of the Army at the time of his conscription examination. In peacetime, those picked for conscript training, released after two years of active service, became members of the First Reserve. Those picked for a short term of replacement training formed the Conscript Reserve.

Both trained groups automatically entered the First National Army on reaching the age of 37. All other males 17-40 (now 17-44) who were not declared “unfit” became members of the Second National Army, a large body of untrained militia subject to call in emergency.

Japan has declared her intention to employ this reservoir of civilian manpower in local defense of the homeland and overseas areas, While It is true that Japanese civilians have not been used too effectively in the areas already attacked (see Bulletin 10), the following factors indicate that the employment of this Japanese “people’s army” will become more important as the war nears Japan Proper:

-

- Greater numbers of Japanese nationals will be encountered

- The Army has had greater experience in handling civilians

- The individual’s determination to fight will increase as the threat to the homeland becomes more imminent

The available numbers, the past employment, and preparations made by the Japanese for the use of these civilian fighters, and the general methods of employment are discussed below.

It must be remembered that the Japanese Army will also continue to use natives as far as possible for military labor and as auxiliary forces, but this study is concerned only with the less variable use of Japanese nationals residing in operational areas.”

The report concluded that 17,450,000 men aged 15-59 were available as militia troops in the Japanese home islands.

“The proportion of the above numbers actually available as effective fighting men will be limited by several factors, including local administrative problems and the ability of the Japanese to arm and equip the personnel present in areas under attack.”

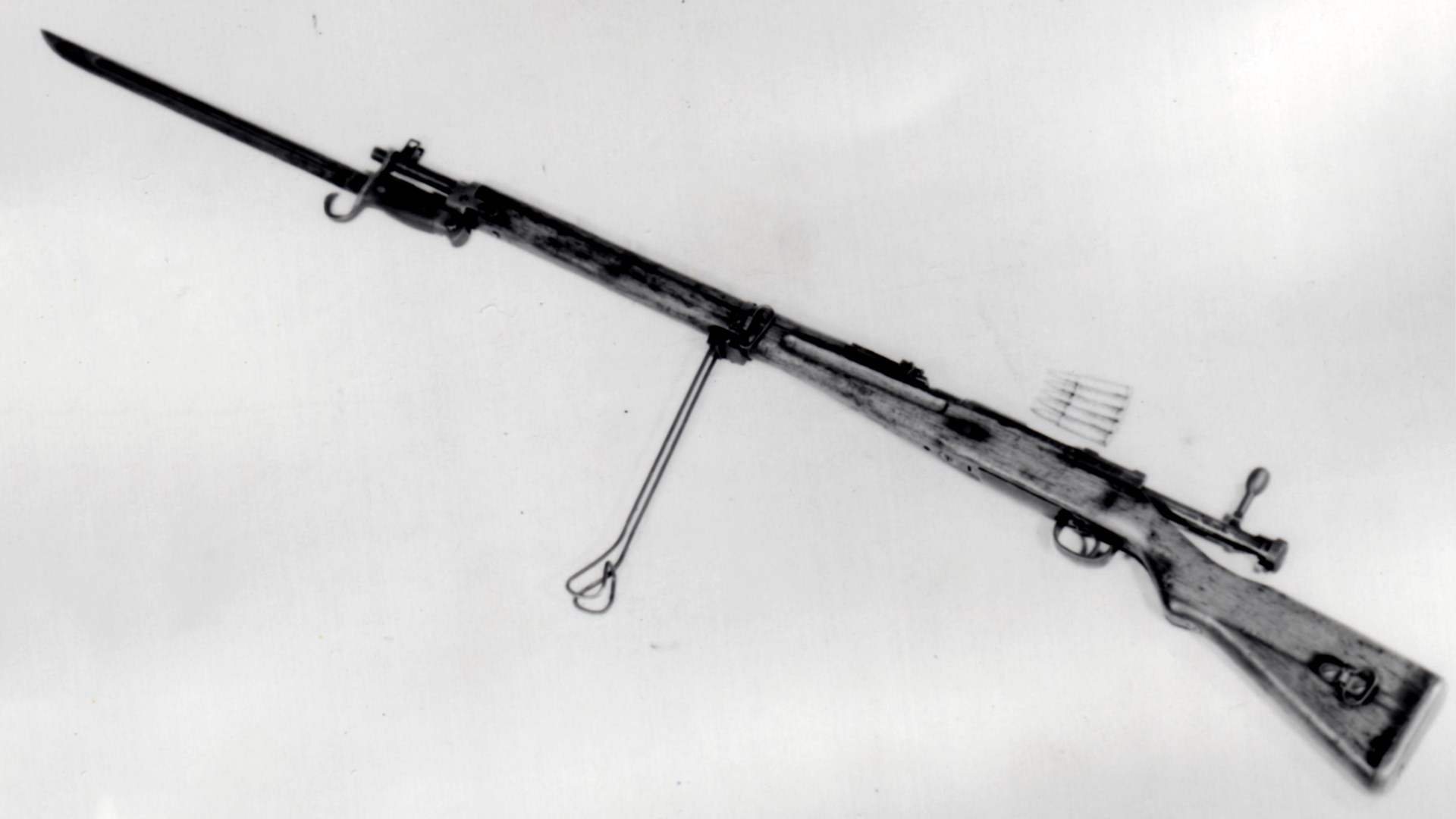

U.S. troops in the field captured various new and modified Japanese wfirearms. Of particular interest were the modifications to the Japanese Model 99 (1939) Pattern 7.7 mm Rifle. These were detailed in an Ordnance intelligence report, produced in late 1944:

“A Japanese 7.7mm rifle of the Model 99 (1939) pattern, recovered in the Ormoc area, is of extreme interest as it Indicates a possible relaxation in the standard of manufacture. The points of variance between this and other rifles of the same model previously recovered are as follows:

-

- The wire monopod has been omitted.

- The anti-aircraft lead arms on the back sight have been removed. Also, instead of the sight being machined in one piece, the sight base is now welded to the mount.

- The bolt knob is smaller and cylindrical in shape, instead of the usual oval ball.

- The safety knob is no longer knurled on its rear face, but is left square, just as it was when it was cut off the lathe.

- The wooden stock is much inferior in quality to that usually fitted.

According to a recently captured document, Japanese ordnance chiefs have expressed grave concern at the lack of essential ordnance supplies. With a view to remedying this condition, it was decided that the manufacture of certain items was to cease, while others were to be modified so that an intensified effort could be made to speed up production.”

The Type 99 7.7 mm Substitute Rifle

In 1943, the Japanese decided to simplify the standard Type 99 rifle and make a “substitute standard” small arm. These modifications included eliminating the sling, cleaning bar and bolt cover, while substituting inferior steel for parts like the bolt and barrel. The simplification eliminated the chromium plate in the barrel, used an inferior grade of wood for the stock, and revised the sight to a range of only 300 meters. This was called a Substitute Type 99 Rifle.

Japanese rifle collectors have uncovered a tremendous amount of information about the nuances of late-war Japanese arms production. Type 99 rifle collectors have described wide variations in the “Substitute Rifle,” including no serial or series number, unnumbered parts, mismatched parts, front sights missing guards, rear sights missing wings, alternate shapes to the bolt handle and varying types of butt plates.

During April 1945, Japan made a significant change in its civil defense forces, designating them as civilian militia, and by June, conscription laws had been enacted even while the militia was renamed the Volunteer Fighting Corps (Kokumin Giyū Sentōtai). By the end of June, more than 25 million Japanese men were deemed “combat capable” by their hopeful government, but very few of them could be equipped with firearms of any kind. The Volunteer Fighting Corps did not see action during the war, but an early precursor, the local home guard on Okinawa, was equipped with obsolete rifles, most notably the Type 22 Murata rifles (11 mm). In the home islands, all that was available in the short term were spears, swords, axes, clubs and crossbows. Hand grenades were the most plentiful of modern weapons.

The Japanese “Simple Rifle:” Crude Weapons For The Massed Militia

Preparing for the invasion they knew would come, the Japanese embarked on a quick program of simple weapons development to equip their mostly untrained militia. The resulting firearms are some of the rarest guns of the entire war. The following descriptions (and photos) come from a series of U.S. Ordnance Technical Intelligence reports compiled during the first few months of 1946.

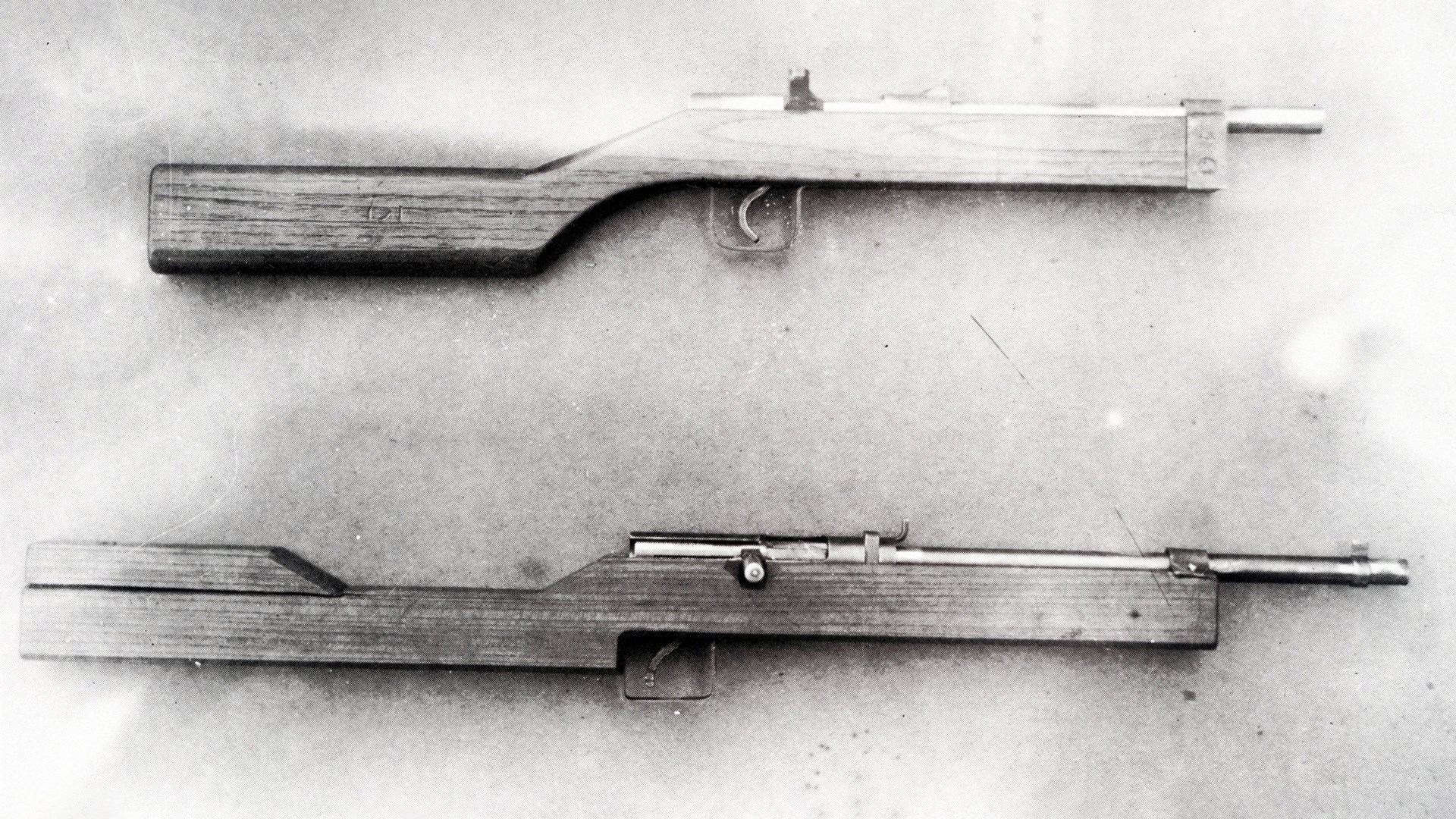

Simple 7.7 mm & 8 mm Rifles

A very simple rifle that would fire the standard 7.7 mm ammunition was attempted. The length of the barrel was 50 cm, and it was so simple in construction that it, as well as the other parts, could be made on an ordinary lathe. It was a bolt-action, single-shot piece that was intended to equip front-line defense troops in an invasion. However, as the ammunition proved too powerful, it was decided to make the rifle shorter and to use standard 8 mm 14th Year Type pistol ammunition, which proved much more satisfactory.

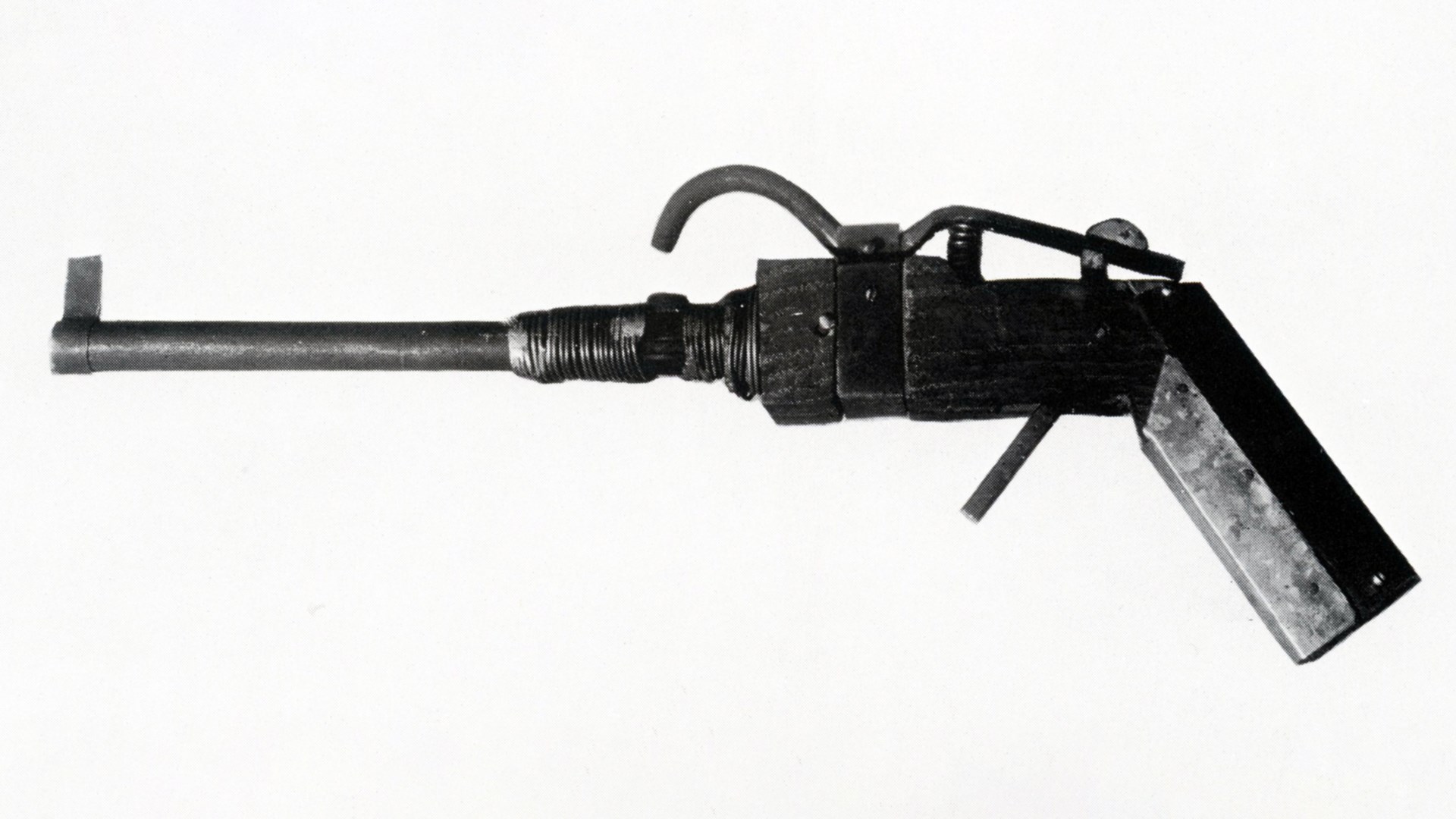

National Rifle & Pistol For Civilian Defense

This rifle was developed for the purpose of equipping volunteer defense troops and was a type that could be made by any small factory or smithy shop. The construction was simple as an ordinary piece of pipe (13 mm diameter) formed the barrel. It was loaded with 3 to 5 grams of blackpowder, and the projectile was made from ordinary bar stock cut in sections about 15 mm in length. It was fired by the hammer striking a primer-igniter cap that was placed over a small flash hole on top of the barrel. A pistol version of this firearm was also produced.

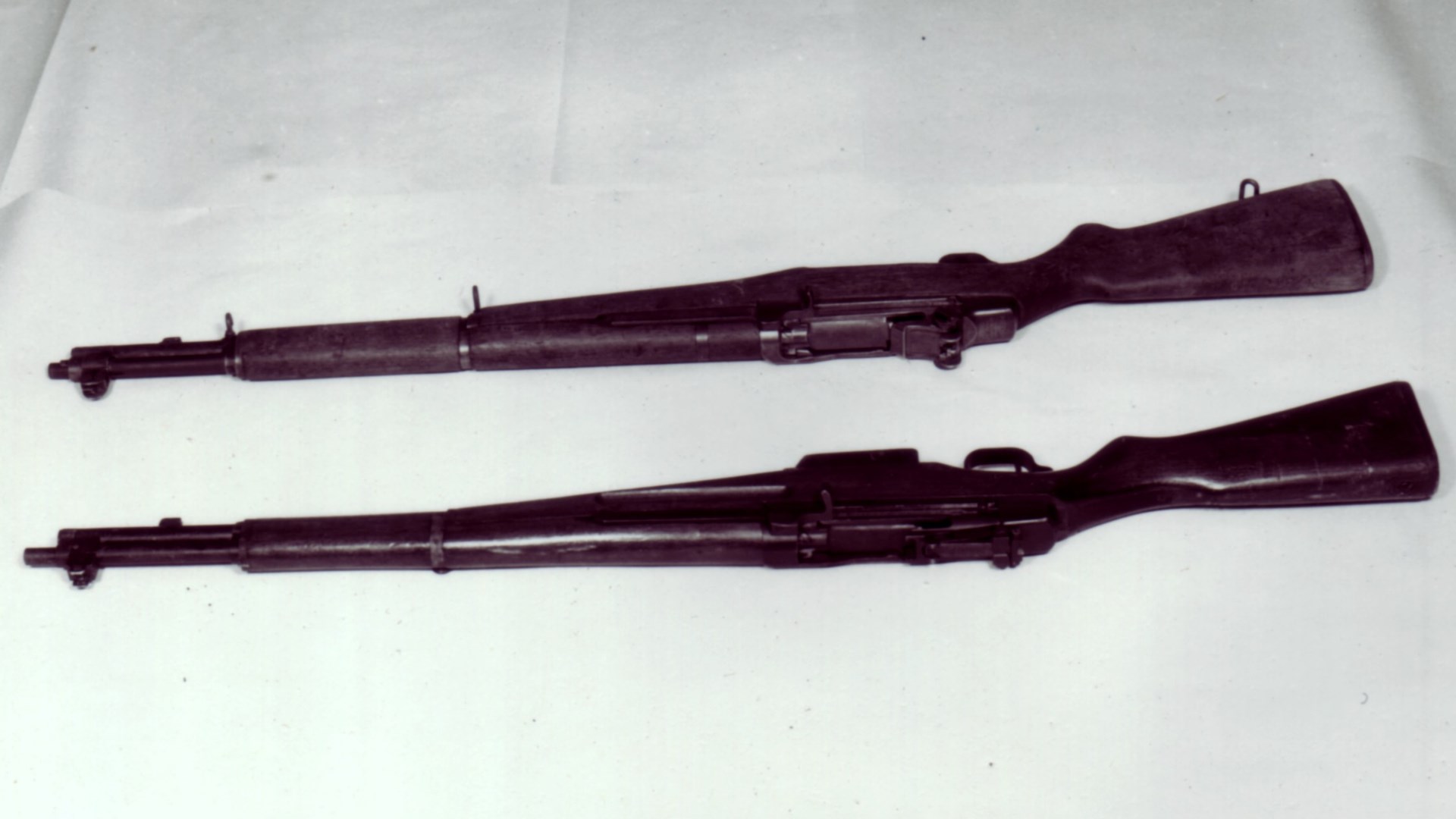

Type 5 Semi-Automatic Rifle (Garand copy)

The need for a semi-automatic rifle for the Japanese army was recognized in 1922, but the development of such a firearm was not begun until 1931 when several models were made; all proved unsatisfactory. This study lasted until 1937, at which time research was temporarily discontinued.

In March 1941, the inquiry was again started because of the progress on semi-automatic rifles in foreign countries. At this time, the 1st Section and the Kokura Army Arsenal designed several types of recoil and gas-operated rifles. The results of tests showed that none of the models were entirely satisfactory in operation, and because of the unforeseen difficulty in manufacturing such a rifle, research was again stopped.

About March 1944, there was a strong demand to develop a semi-automatic rifle, especially from the paratroop command. At that time, the Navy introduced a semi-automatic rifle copied from the U.S. M1 (Garand) Rifle that used the standard Japanese 7.7 mm ammunition. In April 1945, models were finished and tested. Although the test results were not entirely satisfactory due to breakage of parts, loading and feeding difficulties, they were considered good enough to adopt the gun. The rifle was standardized as the Type 5.

World War II finally ended after the atomic bomb attacks on Hiroshima (August 6) and Nagasaki (August 9). While the casualties from the two nuclear blasts were horrific, they pale in comparison to projected number of deaths if dozens of Allied infantry divisions assaulted Japan and Japanese militarist plans to sacrifice the entirety of their population to stop them came to fruition. Armed with bamboo spears and an odd assortment of crude firearms, the Japanese Volunteer Fighting Corps would have inflicted their share of casualties on the invaders, but the utter and tragic destruction of Japan and its people would certainly have followed.

A Winchester 1866 Rifle

How To Pull A Target

THE THEORY AND USE OF THE DESIGNATED MARKSMAN RIFLE

The citizen rifleman is one of the foundations of American gun culture. The images of the Minutemen at Concord Bridge and the defenders of the Alamo are just two examples of how rifle marksmanship has become part of American lore.

The National Rifle Association was founded to provide rifle training for America’s citizens. In addition to this, the Second Amendment revolves around the idea that the common people should have the right to keep and bear arms.

The military also has a need for accurate rifle shooting at longer distances. Britain’s experience with the Kentucky Long Rifle in America led to the creation of dedicated Rifle Regiments in their army, such as the King’s Royal Rifles. These Regiments engaged the enemy at longer ranges than the smoothbore muskets of the regular infantry could manage. That idea took hold in armies all over the world, and the dedicated sniper corps became a fixture in most modern armies.

These Regiments engaged the enemy at longer ranges than the smoothbore muskets of the regular infantry could manage. That idea took hold in armies all over the world, and the dedicated sniper corps became a fixture in most modern armies.

Snipers operate, for the most part, as a separate unit from the regular infantry. Typically, they work in two-man teams, with a sniper and a spotter. The mission of this team is to seek out and engage high-value targets such as military leaders, without support from the rest of the infantry.

The role of the sniper is still very valuable today. However, recent conflicts overseas have shown that a different type of marksman is also needed, one that is integrated into the infantry, not fighting on their own. This is where the idea of a designated marksman and dedicated marksman rifle come into play.

WHAT IS THE POINT OF A DMR RIFLE, AND HOW IS IT USED?

There is no set standard for what makes up a Designated Marksman Rifle, or DMR. However, they tend to have a defining group of characteristics which makes them distinct from a sniper rifle.

- A sniper rifle is typically optimized for engagements well beyond 300 yards. As such, they are unwieldy at closer distances. A DMR, on the other hand, will retain some capability for close quarters combat, while still being accurate out to 500-800 yards.

- A DMR will have a better optic than a standard service rifle. In the past, this meant fixed-power scopes in the 1.5-4x range. Today’s DMR’s tend to have low power variable optics which can zoom from 1x power all the way out to 6x or even 10x. As a comparison, the scope on a typical sniper rifle will start at 4x power (or higher) and go out to 12x power, 16x or higher.

- The action and controls of a DMR will usually be very similar to the other service rifles in a squad of soldiers. A Designated Marksman is tasked with engaging high value targets. This means that he is often engaged by the opposing force’s snipers and marksman. The more that a Designated Marksman can look like an ordinary soldier, the more he can accomplish his mission.

SNIPERS VS. DESIGNATED MARKSMEN

The role of a Designated Marksman is clearly different than the role of a sniper. The rifles used by the two professions are also different.

- A DMR Rifle will usually use a semi-automatic action, while a sniper rifle is typically bolt action. The semi-auto action of a DMR allows for a rapid follow up shot, and also makes the rifle more effective at closer distances.

- The magazine capacity of a DMR Rifle will be higher than that of a sniper rifle. It’s not uncommon for a DMR to use the same magazine as the other rifles in the squad, albeit loaded with more accurate ammunition than the other rifles. This means that a Designated Marksman can have 30 rounds or more on hand, with a sniper rifle usually tops out at 10 rounds of ammunition in a magazine, and often has quite less.

- The accuracy of a Designated Marksman Rifle stops short of the pinpoint precision of a sniper rifle. A DMR will typically be accurate to 2 MOA or less, which is far more accurate than a service rifle, but well under the sub-MOA accuracy of a dedicated sniper rifle.

A HISTORY OF THE DMR RIFLE

The use of the Designated Marksman Rifle by the military started in the late 1930’s in the Soviet army. The Soviets integrated a soldier into each squad to engage and neutralize enemy machine gunners, officers and other targets of value. These soldiers did not use specialized, match grade sniper’s rifles.

The use of the Designated Marksman Rifle by the military started in the late 1930’s in the Soviet army. The Soviets integrated a soldier into each squad to engage and neutralize enemy machine gunners, officers and other targets of value. These soldiers did not use specialized, match grade sniper’s rifles.

Rather, they were almost identical to the standard service rifle the rest of the squad used, but had better sights, such as a glass scope or similar. Squad marksmen in WWII were seldom required to engage targets out to 400 or 500 yards.

However, it was common for snipers to engage targets at that distance. Instead they reached out only slightly beyond the two or three hundred yard effective range of their squad. Their job was to make precise hits that could shift the balance of the battle in favor of their force.

Other nations started to see the value of integrating a designated marksman who could suppress the target with accuracy rather than the amount of lead thrown downrange.

The German Army was quite often on the receiving end of the Soviet designated marksmen, so they created scoped versions of their G43 semi auto rifle, chambered in 7.92x57mm Mauser. The United States also used scoped variations of the M1 Garand, the M1C and M1D models, but those did not see significant use during World War 2.

THE MODERN DMR RIFLE IS BORN

A consensus developed after World War 2 that since the vast majority of infantry engagements happened at distances of 300 yards or less, there was no need to equip a squad with weapons that reached out beyond that distance.

This idea worked for a while. The introduction of lightweight rifles such as the M16, chambered in medium power cartridges worked wonders at those ranges. Just because the majority of engagements happened at less than 300 yards doesn’t mean that all engagements happen at those distances, and the designated marksman rifle came back into vogue.

Soon after World War 2 ended, the Russian Army standardized on the SVD rifle chambered in 7.62x54R, and many other Warsaw Pact countries followed with similar rifles.

The SVD looks similar to the AK-47, the standard assault rifle of the Soviet Union. However, the SVD uses a different operating system and is chambered in a much larger and more powerful round than the AK.

U.S. DESIGNATED MARKSMAN RIFLES

The United States initially went in a similar direction to the Soviet Union, used scoped variants of the standard issue M14 battle rifle and its semi-auto only cousin, the M1A as DMRs. There are also accurized versions of the M16/M4 that are quite commonly used as a DMR. For instance, the Marines now use the M38 Squad Designated Marksman Rifle, an accurized version of their standard M27 gas-piston operated rifle.. This rifle replaced Mk12 Special Purpose rifle, an M16 variant chambered in 5.56mm.

In recent years, the AR-10 platform has gained wide acceptance as a Designated Marksman Rifle, especially in the United States. Just as the SVD has cosmetic similarities with the AK-47, The AR10 looks very similar to it’s smaller cousin, the AR-15.

However, the AR-10 is chambered in larger, more powerful cartridges than the AR-15, such as 7.62x51mm and others. The Knights Armament SR25 and M110 rifles are two examples of this type of rifle that are in common use by the military today.

PRECISION AND ACCURACY MATTER TO CIVILIANS, TOO

DMR’s are not just for the military, however. A Designated Marksman Rifle is designed to engage targets at longer ranges. This means they make excellent hunting guns when chambered in appropriate calibers. DMR-style guns are also well-suited to 3 Gun competitions. 3 Gun matches have targets at distances ranging from one foot to 400 yards or more are in common use.

In addition to this, they are also great fun at the range. Making shots with a DMR at 300 yards or more, with less expensive calibers like 5.56mm and .308 Winchester is a good way to stretch out your shooting capabilities without breaking the bank.

Owning a Designated Marksman Rifle is a good way to reach out to distances beyond what a service rifle can do, while still retaining all the qualities of the service rifle you know and love.