IMAGE SOURCE,GETTY IMAGES

IMAGE SOURCE,GETTY IMAGESA medieval English law dating back nearly seven centuries is now at the heart of the most important US Supreme Court gun case in a decade.

The case – which stems from a New York legal battle – challenges a state law that requires that gun users who want a concealed carry permit first prove they have a valid reason.

To help them determine how broad the rights of America’s many gun owners go, the country’s nine supreme court judges are also looking back to the 1328 Statute of Northampton, which dates back to the reign of Edward III.

Here’s what we know.

On Wednesday, the Supreme Court heard oral arguments in the case of the New York Rifle and Pistol Association v Bruen, which revolves around New York’s laws governing concealed carry licenses.

The laws require that residents who want a license to carry a concealed pistol must prove they have “proper cause” for it and that they face “a special or unique” level of danger.

The plaintiffs in the case, Robert Nash and Brandon Koch, applied for a concealed carry permit but were denied, although they were given licenses that allow them to carry guns for recreational purposes such as hunting and target shooting.

With the support of the New York Rifle and Pistol Association – which is affiliated with the National Rifle Association (NRA) – in 2018 Mr Nash and Mr Koch filed a lawsuit challenging the constitutionality of New York’s “proper cause” requirement and handgun regulations.

Their case was dismissed by a federal court in New York, a decision that was affirmed by an appeals court. This, in turn, led the Supreme Court to hear the case.

IMAGE SOURCE,GETTY IMAGES

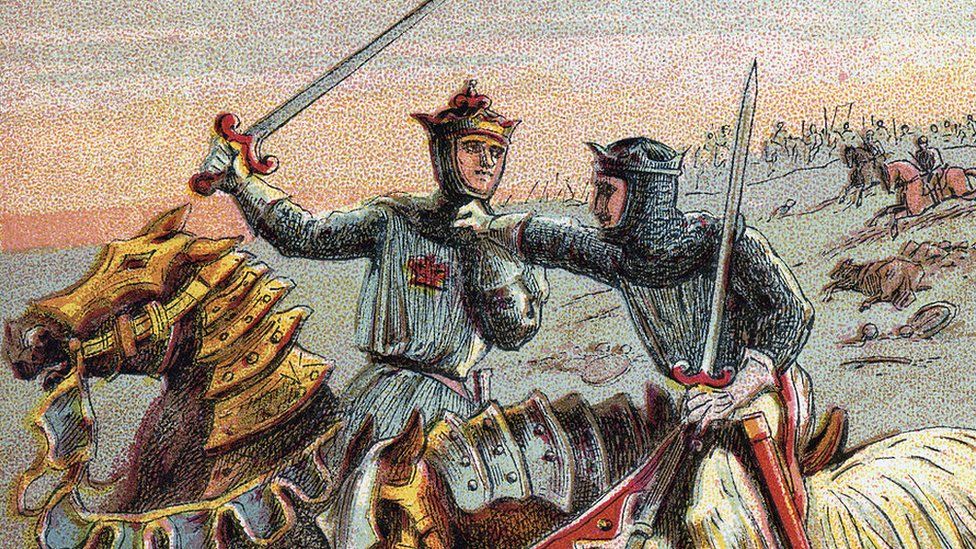

IMAGE SOURCE,GETTY IMAGESIn a separate 2008 Supreme Court case that struck down strict Washington DC handgun laws, the late Justice Antonin Scalia argued that the Second Amendment to the US constitution codified “a pre-existing right” from England.

He added that by the time the United States was founded in 1776, the “right to have arms had become fundamental for English subjects.”

Some historians, however, have disagreed with that assessment, noting that by the late 1200s, English authorities had passed laws restricting the right to carry weapons while traveling in public or in London.

The later 1328 Statute of Northampton – which predates the first recorded use of a firearm in Europe by several decades – declared that nobody “except the King’s servants in his presence” will “go nor ride armed by night nor by day” in fairs, markets “nor in no part elsewhere”.

Lawyers for New York, for their part, have written to the Supreme Court that from the Middle Ages onward, laws “broadly restricted the public carrying of firearms and other deadly weapons.”

Saul Cornell, an American history professor at Fordham University, said he believes it is “beyond ironic” that US gun advocates would look to England as the foundation of their view on gun rights.

“England was a super hierarchical society, and one in which the King has a monopoly of force and violence,” Mr Cornell told the BBC. “I’m not sure how anyone could conclude that this was a society that nourishes this robust, libertarian view of arms.”

“It just doesn’t make any sense whatsoever to any who really understands the complexity of English history,” he added. “Obviously, that doesn’t include many people in the gun rights community or many people sitting on some courts in America.”

Gun rights advocates argue that the Statute of Northampton is being misinterpreted.

In a brief for the Supreme Court, attorney Paul Clement – who represents Mr Nash, Mr Koch and the New York Rifle and Pistol Association – wrote that the statute was only meant to control “unusual weapons” that would frighten the public.

Stephen Halbrook, a firearms law litigator and author, told the BBC that he believes New York “is really reaching and trying to find a precedent to restrict the right [to bear arms] based on Northampton”.

“It was held to apply to carrying arms in a way that terrified other people, not just carrying peacefully,” Mr Halbrook added. “It just didn’t say what New York urges the court it means.”

A Supreme Court ruling against New York in the case would have far-reaching implications for states that have similar restrictions on concealed carry licenses. Six other states have requirements that gun owners show “proper cause” for such permits.

During oral arguments on Wednesday, several justices signalled a willingness to reverse or limit New York’s “proper cause” requirements.

Justice Brett Kavanaugh, for example, asked New York’s solicitor general, Barbara Underwood: “Why isn’t it good enough to say I live in a violent area, and I want to defend myself?”.

Mr Halbrook said that he believes that it is likely that if the court rules against New York “these other states are going to have to revise their statutes to be in accord with this new case.”

“It’s looking that way, but you never know,” he said. “I think the court would simply cross out the requirement that an official has to determine a proper purpose or special need.

“All the other requirements would still be there, such as law-abiding training and things like that.”