Category: All About Guns

Winchester Model 1895 in .405 Win.

Winchester’s famous Model 1895 celebrates its 125th anniversary with the .405 Win. chambering.

On the left side of the receiver, you’ll find one large threaded hole and two smaller ones fitted with screws. These permit installation of a receiver sight. At one time Lyman made a sight specifically for the 1895; today you can get a reproduction of the sight from Buffalo Arms. Just be mindful that when shopping for sights you’ll see references to 1895 that refer to Marlin and not Winchester.

Williams still makes a receiver sight for the Winchester 1895, but the company notes its FP-Winchester 71 will not fit on .405 Win. versions of the rifle.

I love the wood on this gun. It’s oil-finished black walnut, nothing fancy but with a handsome grain. The checkering is done in a bordered point pattern, and it’s very nicely executed. The well-shaped fore-end feels good in the hands and features a graceful Schnabel tip. Wood-to-metal fit is proud all the way around, but at least it’s consistent. As befits a lever action of its era, there are no sling swivel studs.

The buttstock has a plain, black metal buttplate. It’s traditional, if not particularly comfortable to shoot.

While the current rifle is also available in .30-06, I think for most people the .405 Win., which made its debut in 1904, will be the more interesting chambering. It’s a straight wall with a case length of 2.583 inches, longer than both the .444 Marlin (2.225 inches) and .45-70 Gov’t (2.105 inches).

Hornady’s current load throws a 300-grain pointed softpoint bullet at 2,200 fps out of this rifle, and for once the chronograph figures I got exactly matched the book specs. That translates to 3,225 ft.-lbs. of energy at the muzzle.

To put this in context, it’s considerably more energy than most 300-grain .45-70 loads (around 2,200 ft.-lbs.), although, of course, factory loads for the Government are purposely held low because of all the old rifles out there. The .405 also outdoes Hornady’s 265-grain LeverEvolution load in the .444 Marlin at 3,180 ft.-lbs., but the .444 Marlin Superformance (3,389 ft.-lbs.) and LeverEvolution .450 Marlin (3,572 ft.-lbs.) are more powerful.

Roosevelt felt the .405 was a fine lion cartridge, but he and his son Kermit also used it to take rhinos and even elephants. Results on the latter were decidedly mixed, and Roosevelt admitted it was a bit wanting at the largest end of the game spectrum.

“Our experience had convinced us that both the Winchester .405 and the Springfield .300 [.30-06] would do good work with elephants; although I kept to my belief that, for such very heavy game, my Holland .500/450 was an even better weapon,” he wrote in African Game Trails.

As an aside, I was discussing this cartridge with Craig Boddington, and he told me his daughter Brittany used the .405 Win. on Cape buffalo. However, she was shooting the cartridge in the stronger Ruger No. 1 action, which allows the round to be loaded much hotter and with heavier bullets than would be safe even in a modern-built 1895.

So if this cartridge has acquitted itself well in the hunting fields, why is it so obscure? Part of the reason is its oddball .411 bullet diameter. It’s close to the .410 diameter of the .450/400 Nitro Express 3-inch, which is justifiably admired as a dangerous-game cartridge, but the Nitro pushes a 400-grain bullet at 2,050 fps for 3,700 ft.-lbs. of energy.

From there, you’ve got the various powerful .416s, which use .416-inch bullets as their designation suggests. And then there’s the .404 Jeffery, a superb dangerous-game round. Ironically, while .405 is a bigger number than .404, the Jeffery takes a .423-inch bullet.

Bullet size notwithstanding, even in the .405’s heyday the majority of big game hunting in the United States involved deer-size game, and while today you would include hogs as well, then as now there isn’t a ton of call for a cartridge on the .405’s power level.

But speaking of wild boar, Boddington said with the standard 300-grain load it’s “lights out” on hogs, and it certainly has enough energy to tackle the biggest North American game. And today we’re seeing a resurgence in straight-wall cartridges due to some formerly shotgun-only states now allowing straight-wall centerfires for deer hunting. Could the .405 fit in here?

If you zero at 100 yards, the .405 is dropping 8.3 inches at 200 yards and 30.2 inches at 300 yards—with 1,727 ft.-lbs. and 1,250 ft.-lbs. of energy respectively. While that’s a lot of energy, it doesn’t stack up as well in terms of trajectory. Cartridges like the .350 Legend, .450 Marlin, .444 Marlin and .450 Bushmaster are dropping in the 4.5- to 5.7-inch range at 200 yards, with the .45-70 close to seven inches.

But trajectory is just a number. If you range-confirm your drop and do the math, you can still hit your target—and with the .405 you can be sure you’ll be delivering sufficient power.

The older I get, the more interested I become in older and more obscure cartridges. The .405 Win. certainly qualifies, and I think the 1895 would be a fantastic wild boar, elk, bear or moose hunting companion, and it would be a unique deer rifle as well.

I grant you it’s not a ton of fun from the bench. The straight stock with its 27/8-inch drop and hard metal buttplate accentuate recoil forces, but it’s way more pleasurable to shoot than a big, high-pressure magnum.

I did manage to generate some good groups from the bench with the iron sights, albeit at 50 yards. One hundred yards ain’t happening with my eyes and sights like these, at least not for a realistic assessment of the rifle’s accuracy potential. However, I found that by placing the gold bead of the front sight so it sat just atop the fine portion of the notch, I could get an okay sight picture.

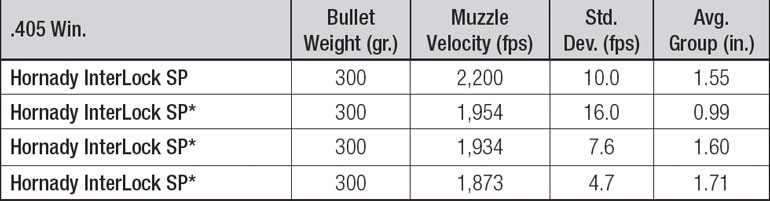

While the .405 is distinctly lacking in factory offerings, fortunately for the 1895 it loves Hornady’s 300-grain load. The average wasn’t bad, and I was able to shoot one group under an inch, all shots touching—indicating that with younger eyes and/or an aperture sight you could get plenty of accuracy. I did shoot a couple 100-yard groups just for fun, and they came in around 2.5 inches—generally in line with what I got at 50 yards.

I worked up four handloads with Hodgdon H4198 and the same Hornady bullets found in its factory ammo. I began with the starting load listed in the Hodgdon manual and ended one grain short of max. The rifle didn’t like the starting load at all, and it’s not included in the accompanying accuracy chart. It’s interesting to see how the accuracy improved as velocity went up, so this gun seems to like ’em on the warm side.

Shooting from field positions was fun. The lever works smoothly, and the rifle comes back on target reasonably quickly thanks to its eight-pound weight—which isn’t a bad field-carrying load at all. At 50 yards offhand I could keep all of my shots in a volleyball with a relatively rapid rate of fire. I also shot the rifle from unsupported sitting at 100 yards and would have all the confidence in the world I could hit a six-inch vital zone every time.

Cartridges load easily into the straight-stack internal magazine, snapping home with a satisfying “snick.” Feeding was flawless.

I always find it enjoyable to work with a rifle that has a storied history, and the Winchester 1895 certainly has one. Winchester sees it much the same way.

“The fact that we’re still producing the M95 is a huge testimony to the Winchester brand and the position it has in the marketplace,” Nielsen said. “Few companies get to claim they are still building the same guns that brought them to the table. If we can still build and sell a gun designed over 100 years ago, then we’re doing something right.”

You’ll get no argument from me on that score. I love the latest, greatest cartridges and gun designs we have available to us today—we’re living in a golden age, for sure—but there’s a lot to be said for a 125-year-old design and 116-year-old cartridge that are still ready, willing and able to continue to serve America’s hunters.

Winchester Model 1895 Specs

- Type: Lever-action centerfire

- Caliber: .30-06, .405 Win. (tested)

- Capacity: 4-round internal magazine

- Barrel: 24 in., 1:10 twist (as tested)

- Weight: 8 lb.

- Overall Length: 42 in.

- Finish: Brushed polished

- Stock: Black walnut

- Sights: Open; gold bead front

- Safety: 2-position sliding tang

- Price: $1,180

- Manufacturer: Winchester, WinchesterGuns.com

Winchester Model 1895 Accuracy Results

When the United States became actively involved in the First World War during the spring of 1917, our troops deployed to France soon found themselves in the unfamiliar environment of trench warfare. Since an important component of such fighting was periodic raids on enemy trenches, guns that were capable of being effectively wielded in close confines were particularly valuable. Handguns weren’t sufficiently powerful, and the standard Model of 1903 and Model of 1917 rifles were too long, cumbersome and slow- firing to be truly effective in such situations. Clearly, another type of arm was needed, but there was some debate as to just what it should be.

When deciding on what type of trench-fighting gun would be most efficacious, some senior Army officers, including Gen. John J. Pershing, then commander of the American Expeditionary Forces, remembered their experiences in the Philippines almost two decades earlier. When the United States gained possession of the Philippines from Spain following the Spanish-American War of 1898, our troops were faced with the unpleasant task of battling several indigenous groups who had fought the Spanish for decades and looked upon the Americans as just another occupying force.

Foremost among these were the fierce Moro tribesmen who exacted a deadly toll on American troops in close-quarters combat. The standardized .30-40 Krag rifles and .38 Long Colt revolvers proved to be unequal to the task, and a more effective arm was sorely needed. Circa 1900, the U.S. Army purchased some 200 of the newly introduced Winchester Model of 1897 short-barrel, slide-action shotguns for use in the ongoing “pacification” campaigns in the Philippines.

These “sawed-off” shotguns proved to be devastatingly effective close-quarters guns and were instrumental in eventually helping to quell the bloody uprisings.

Given the effectiveness of shotguns in the Philippines, it was recognized that a short-barrel, 12-ga. repeating shotgun loaded with 00 buckshot would also be a formidable tool in the trenches of France. It was decided to develop a shotgun specifically modified for trench warfare.

It was logical to base the new weapon on the tried and proven M1897 shotgun, but the War Dept. stipulated that the gun must be capable of mounting a bayonet. The M1897s previously used in the Philippines were standard commercial-production, plain-barrel “riot guns,” so a method of mounting a bayonet on the proposed shotgun had to be devised.

Working in conjunction with Springfield Armory, Winchester developed a metal one-piece bayonet adapter/handguard assembly. Since it would be necessary to grip the barrel to properly wield a bayonet-equipped shotgun, the assembly had a ventilated metal handguard for protection from a hot barrel.

The adapter was designed for use with the M1917 bayonet as used with the M1917 rifle. The new combat shotgun was soon dubbed the “trench gun,” although this was not official nomenclature. Production contracts were given to Winchester for the new firearm.

Since it was believed the new “trench gun” would be a valuable addition to our Doughboys’ arsenal, the Ordnance Dept. solicited proposals from other manufacturers for bayonet-equipped versions of their repeating shotguns. Remington Arms Co. submitted a “trench-gun” variant of its Model 10 slide-action repeating shotgun. Rather than the all-metal one-piece handguard/bayonet adapter used with the Winchester gun, the Remington Model 10 design featured a wooden handguard and separate bayonet lug, also adapted for the M1917 bayonet. The modified Remington Model 10 was adopted and put into production. The U.S. Army now had two standardized “trench guns,” but other models continued to be evaluated.

Although Remington had accepted large contracts for arms from other nations—chiefly Pattern 1914 rifles for Great Britain and M1891 Mosin-Nagant rifles for Russia— the company was still looking for additional business. Since the American government had adopted the Model 10 trench gun, the company believed that such guns might appeal to other nations but recognized that these potential purchasers likely wouldn’t be interested in a shotgun designed to use the U.S. M1917 rifle bayonet. Remington had a rather large number of “saber” bayonets for its No. 5 rolling-block rifles left over from previous South American contracts. The company submitted a standard Model 10 shotgun with a metal bayonet lug brazed to the underside of the barrel. However, no type of protective handguard was provided, which obviously limited the gun’s effectiveness in bayonet fighting. A prototype was submitted to the Ordnance Dept. for review, but little interest was shown, and it was rejected.

Undeterred, Remington turned its attention to the Russian government, which had placed large contracts for M1891 Mosin-Nagant rifles and bayonets. The Russian bayonet was an all-metal socket design with a cruciform blade. Having learned from the previous unsuccessful submission, the proposed “Russian trench gun” was equipped with a wooden handguard somewhat similar to that used on the U.S. Model 10 trench gun. The bayonet was locked into a metal flange and was not attached to the barrel as was the norm with most bayonets. Although it appeared to be a functional design, the fall of the Czarist government resulted in no real consideration being given to the gun, and it was discarded as well.

After these two abortive modified Model 10 prototypes, Remington came up with one of the most novel ideas for a trench gun ever conceived. A popular gun in the company’s product line was the semi-automatic Model 11 shotgun designed by the legendary John Moses Browning. It was believed that such a gun would be ideal for trench warfare due to its impressive rate of fire. There was, however, one major problem: The Model 11’s recoil-operated mechanism required that the barrel move back and forth with each shot. Since Ordnance specifications for trench guns mandated that they be equipped with a bayonet, Remington engineers had to devise some method of overcoming this inherent problem. Mounting a bayonet on the barrel wouldn’t be feasible because the added weight would not allow the barrel to reciprocate properly. Also, if a barrel-mounted bayonet was thrust into an adversary, the barrel would move backward and could, at least partially, eject a chambered shell, resulting in a jam.

The problem was ingeniously addressed by mounting a metal sleeve (tube) to the front of the receiver into which the barrel was fitted. A bayonet lug could be attached to the sleeve that didn’t affect the reciprocal movement of the barrel. In order to permit the gun to be properly grasped for bayonet fighting, a wooden fore-end that served as a handguard was fitted. There were at least two variations of the design that differed primarily in length with a slightly greater tubular magazine capacity for the longer pattern. It appeared to be a rugged and functional arm that likely would have been quite effective for its intended purpose.

The prototype Model 11 trench guns were completed by the fall of 1918, around the time of the Armistice. However, with the war ending, the Ordnance Dept. abandoned further consideration of the shotgun. The prototypes were shelved, and, perhaps surprisingly, the concept was never revisited. It is intriguing to think that if the gun had been available a year or so earlier, it might have been adopted. As events transpired, even though the Model 11 trench gun never made it past the prototype stage, large numbers of plain-barrel Model 11 riot guns (and long-barrel training guns) subsequently saw service during World War II.

In addition to the Remington designs, there was another proposed trench gun fabricated and submitted for testing in 1918. The J. Stevens Arms and Tool Co. developed a trench gun based on its Model 520 slide-action shotgun. Rather than using a wooden handguard, like the Remington guns, or a one-piece metal handguard/bayonet adapter assembly, like Winchester, Stevens equipped its gun with a ventilated metal handguard and a separate bayonet lug on the barrel. The shotgun reportedly acquitted itself quite well in testing, and it is speculated that a small number may have been purchased, but this is unconfirmed. Unfortunately for Stevens, like the Remington Model 11 prototypes, the end of the war resulted in the cancellation of all pending contracts. Stevens had better luck with a trench-gun version of the Model 520-30 (an improved 520) during World War II when substantial numbers were procured and issued along with some Stevens M620A trench guns.

If the First World War had lasted into 1919 as had been expected, it is possible that at least two additional trench guns, the Remington Model 11 and Stevens 520, could have found their way into the trenches. Instead, the only two trench guns to be issued during the war were the Winchester M1897 and the Remington Model 10. Nevertheless, the efforts to develop innovative designs for a new type of combat arm, the “trench gun,” illustrate the resourcefulness and expertise of American gunmakers at a critical time in our history.