Category: All About Guns

Milsurp Operator: M1 Carbine

FN M249 SAW

The intricacies of World War 1 small arms fill books due to the rapid advancement of technology and how warfare changed in a few short years. It’s easy to get wrapped up in calibers, firearm models, bayonets, and actions as you pour over the history of the world’s first Great War. As such, sometimes things get forgotten and the world finds itself in need of a reminder. If I asked you what rifle the American forces used in World War 1, for instance, you’d likely say the Springfield 1903. You’d be partially right, but only about 25% or so. The M1917 Enfield actually did most of the fighting.

The Springfield 1903 certainly served overseas, and if you asked video games and movies, then you’d be led to believe it was the only American service rifle fighting that war. The Springfield name is absolutely legendary, and at the time, the Springfield 1903 was the official service rifle of the United States. Yet, 75% of American troops carried the Enfield M1917, and only the paltry remainder actually carried the Springfield rifle.

This includes Medal of Honor recipient Alvin York who silenced machine gun after machine gun with his M1917 and M1911 pistol. However, if you watch the Gary Cooper rendition, he wields a Springfield M1903. If the Springfield 1903 was the American service rifle of the time, then you might be asking: why did the M1917 Enfield arm the whopping majority of American troops?

Well, my dear reader, it’s simple logistics.

The M1917 Enfield and A Tale of Victory

You see, Americans are typically a little late to World Wars. However, we often help our allies in some big ways once we show up. The Brits had recently changed rifles and calibers, and when World War 1 came around, they were in need of rifles… but they clung to an old caliber to simplify logistics. They couldn’t build their P14 rifles quick enough to meet their needs, so they contracted with American weapon manufacturers to produce more.

American factories were spitting out P14 rifles left and right, chambered in the old .303 British. This helped the British forces greatly, but by the time America got involved in the war, they had the exact same problems the Brits had. There weren’t enough rifles to go around. Specifically, not enough Springfield M1903 rifles.

So, they looked at the factories building Enfield rifles and planned to retool them to make America’s Springfields instead. Then someone had a much better idea. Let’s just make P14s for American forces.

It would be much faster to produce Enfields for America than to retool the factories for Springfield rifles. They would be chambered, however, in the American 30-06 U.S. Service cartridge and were modified as such to accommodate the round. Luckily since the original rifle was itself designed for a powerful new British round, it accommodated the American 30-06 just as easily. Thus the M1917 Enfield was born.

American forces eliminated the volley sights and added a 16.5-inch bayonet to the end. The Enfield M1917 would quickly deploy with American Expeditionary Forces and fight in the fiercest battles of World War One.

Inside the M1917 Enfield

M1917 Enfields were very robust guns. While many of us may think of bolt action rifles as light hunting rifles, these guns were from that. They weighed nearly 10 pounds, featured 26-inch barrels, and an overall length of 46.3 inches.

The M1917 Enfield held five rounds of .30-06 and could be loaded via individual rounds or through stripper clips. Stripper clips allow for rapid reloads via simple disposable clips that hold five rounds by their rim.

Soldiers aligned the stripper clip with the integral magazine of the weapon and pressed downward, loading the magazine rapidly and allowing the soldier to jump right back into the fight. It may sound slow by today’s standards, but it was pretty quick in its day.

The bolt throw and movement on the M1917 Enfield were rapid and smooth. Enough so that the Enfield rifles gained a reputation for having a faster firing rate than the Springfield rifles. At close range, a faster firing rate is quite valuable (as was the 16.5-inch long sword bayonet).

Accuracy In Combat

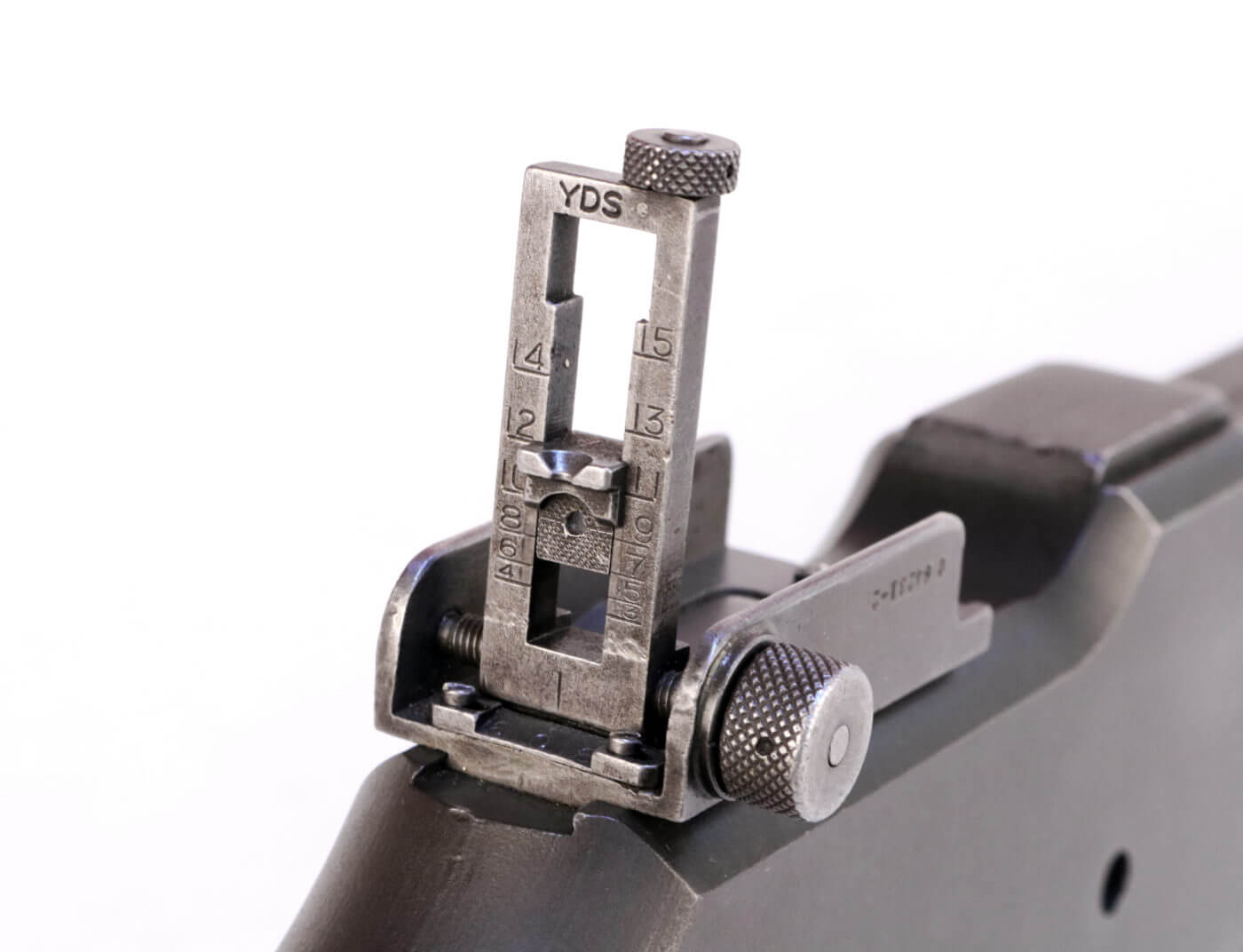

Americans and Western European forces placed a good amount of value on accuracy in their rifles, and that’s apparent in the M1917. It wore a peep sight that was suited for long-distance engagements. In that role, the sight allows a soldier to carefully aim and take a precise shot. That’s great on an open battlefield, but sucked for close-range fighting in the trenches.

The peep sight allowed the M1917 to be more accurate than the M1903 in the early days, but later models of M1903 incorporated them as well. However, the M1903 sights of World War 1 weren’t incredibly effective. They were too far from the eye, and the front sight was thin and hard to see. It also broke quite often.

Accuracy with the M1917 was top-notch, and with iron sights, an average shooter could produce three-inch groups at 100 yards. You take a skilled shooter like Alvin York, and you could be a real menace to the enemy with this rifle.

They were accurate enough that the military converted a number of them to sniper rifles with fixed power magnification optics. These rifles were equipped with Winchester A5 scopes which granted the user a fixed five-power magnification that greatly increased their ability to hit targets at long ranges.

The End of the Line

After World War 1 ended, the M1903 went back to being the bell of the ball, though the M1917 stuck around for a while. They were sent overseas and kept in reserves, and later when World War 2 broke out, they were distributed as Lend-Lease rifles. Soldiers in mortar and artillery units carried them into the next Great War until the M1 Garand shortage was over. The M1917 Enfield was a fantastic rifle, and it’s a shame it doesn’t get the respect it deserves.

Hopefully, we’ve helped spread the glory of the M1917 Enfield and the difference it made in the trenches, in Belleau Wood, in Cantigny, and beyond.

In the early part of the 20th century, the bloody killing fields in France and Belgium were chewing up an entire generation. War in the Industrial Age stole life on a scale previously unimagined. Amidst the fetid trench warfare that characterized that tortuous time, the world’s engineers strived to contrive tools to give their nation’s fighting men an edge on the battlefield.

John Moses Browning was the most gifted gun designer who ever drew breath. Born five years before the American Civil War, Browning held 128 firearms-related patents when finally he breathed his last in Liege, Belgium, in 1926. If we had any sense as a nation (we don’t), we would carve his likeness into a mountain someplace.

John Browning was particularly busy in the early part of the 20th century. He bodged up the 1911 pistol along with the M1917 belt-fed, water-cooled machinegun. Based upon specs purportedly crafted by Black Jack Pershing himself, he also designed the 12.7x99mm/.50 BMG round and the beastly M2 machinegun that fired it.

Though originally intended to defeat WW1-era balloons, variations of Browning’s inimitable Ma Deuce heavy machinegun eventually armed every American combat aircraft of WWII.

He also drew up plans for something radically fresh and new. He called this invention the Browning Machine Rifle.

Was It a Mistake?

The Browning Machine Rifle was based upon a thoroughly discredited concept. Military planners felt that “walking fire” might be a good idea on the modern battlefield. In this hypothetical world, soldiers armed with repeating weapons would stand erect and stride purposefully toward enemy positions firing a round from the hip every time a certain foot hit the ground. Naturally, this idea arose with the French. It turned out that in the real world actual flesh and blood soldiers were none too keen to put this dubious tactic into practice. It did nonetheless still birth a most remarkable firearm.

Browning’s Machine Rifle was a monster of a thing that seemed better scaled to David’s Goliath than to normal folk. At 15.5 lbs. and nearly four feet long, the newly christened BAR (Browning Automatic Rifle) was a selective fire beast that fed from 20-round steel box magazines.

Cycling at around 550 rpm on full auto and firing from the open bolt, the BAR offered a quantum improvement over the bolt-action rifles of the day as well as such abominable light machinegun designs like the French Chauchat.

The web gear issued along with those early BAR’s included four double-magazine pouches, a pair of 1911 pouches and a fascinating tin cup scaled to accept the buttstock of the BAR. The theory was that a gunner might lodge the buttstock in this cup and run the gun from the hip as he strolled leisurely toward the Huns’ chattering Maxims. Subsequent WWII-vintage web gear just had six double-magazine pouches and eschewed the cup.

Generations

Some 43,000 early M1918 BARs were shipped to Europe by the end of WWI. Of those, 17,664 were issued to the American Expeditionary Forces, and 4,608 actually saw action. These were the variants that were later stolen by Clyde Barrow from National Guard armories and used on his reign of terror across the American heartland during the gangster era.

A modification dubbed the M1918A1 sort of fizzled, but by 1939 the basic BAR chassis had been upgraded to the M1918A2 standard. A great many earlier guns were arsenal rebuilt into the more modern configuration. A2 upgrades included a bulky folding bipod, a redesigned flash hider, reimagined furniture and fresh entrails. The new three-position selector offered safe, slow and fast options. The cyclic rate on slow was around 350 rpm, while the fast rate was about 550 rpm.

The demand for walnut for rifle stocks threatened to denude American forests, so Firestone Latex and Rubber developed a synthetic substitute for the M1918A2 BAR. These early composite buttstocks were molded from a fabric-reinforced plastic that rendered fine service. Most wartime BARs sported this sort of furniture.

The M1918A2 ultimately weighed 20 lbs., a full 4.5 lbs. more than the original M1918. As a result, a great many BAR men in WWII removed their bipods, monopods and sometimes flash suppressors in an effort at cutting down weight. The carrying handle that affixes around the barrel was adopted very late in the war and didn’t really see service until Korea.

Practical Magic

The BAR is a massive bulky beast that fires a comparably massive 7.62x63mm/.30-06 round. I honestly cannot imagine humping this thing through a fifteen-mile forced march. The leather sling is fairly wide, but the gun remains just huge. I think perhaps those old guys were just tougher than we are today.