Category: All About Guns

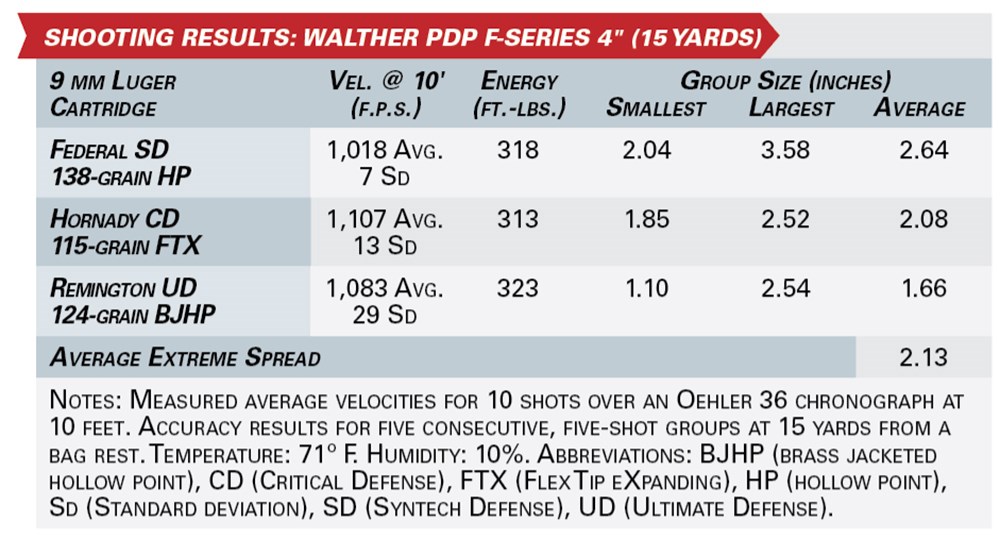

For the full story on the Walther Arms PDP F-Series, see Walther PDP F-Series: A Win For Women.

The Walther PDP F-Series is a 9 mm duty pistol intended for serious use—competition, personal protection, law enforcement—for women, and it has well-thought-out features and ergonomics intended to meet their needs. So, how did Walther approach it? In short, with input from serious women shooters and engineers at every step of the development and design process.

Setting out to adapt its Performance Duty Pistol (PDP) to female shooters resulted in Walther creating a completely new frame. Although it has the lines of the PDP, especially through the slide, the rear of the F-Series frame is completely different, dimensionally, in its trigger reach and even in its striker-fired operation. This isn’t just a new backstrap and a marketing campaign—it’s a new gun.

With the PDP, Walther created one of the top (and most accurate) duty handguns made anywhere by anyone. You can read about what Field Editor Justin Dyal thought in “Best In Class? Walther’s New PDP”, and you can look up the two NRA Golden Bullseye awards it has notched. So, Walther wisely started with that solid foundation and kept the PDP Compact’s excellent 15-round magazine as well.

When asked about what makes the F-Series different, Carl Walther GmbH President and CEO Bernhard Knöbel said, “Number one is the trigger reach. Circumference is important, but shape is more important. It has a grip that has a little bit of a humpback that forces the female hand into the frame and closes the gap underneath. That makes the biggest difference, I think. Then there’s ‘rackability’ of the slide. From shooters who handle the F-Series for the first time, you hear, ‘Wow.’ That’s the biggest compliment you can get.”

Those not in the competition-shooting arena might not know that Walther builds target handguns, such as the GSP used in Olympic rapid fire, as well as LP500 airguns used at a very high level. Each of those guns must be custom-fitted, so Walther measures the hands of each shooter and builds them one at a time. It developed a database of thousands of women’s hands that aided in the creation of the F-Series. But the company also received input from some of the top women shooters and trainers in the United States, including Gabby Franco and Tatiana Whitlock. The latter told me how modified frames were shipped back and forth between here and Germany. Material was added or removed each time to get the frame dimensions just right. It’s north of $100,000 to have a new frame mold created. That, ladies and gentlemen, is called an investment.

So how did they do it? Walther concentrated on three areas. The first was trigger reach, followed by contouring the grip to better fit the smaller—and not as wide—hands of most women, and finally, as Knöbel called it, “rackability,”

Compared to a PDP Compact, the circumference of the F-Series grip was reduced from 7 7⁄8″ to 6 7⁄8″. Gone are the subtle swells for the fingers of the PDP—jettisoned to get the grip more svelte. The sides of the frame were slimmed from 1.187″ to 1.151″. Also, the beavertail of the grip frame was re-designed to better fit female hands. It has more material because women’s hands, typically, aren’t as bulky at the web. This allow a woman’s hand to get a proper high grip, keeping the gun anchored. The difference might seem mathematically small, but when combined with reduced trigger distance, it is like night and day. By reducing the frame’s fore-and-aft dimension, it allows smaller-handed shooters to better reach the reversible magazine release on the grip frame, too.

The F-Series employs a new two-piece striker design, differing from the original PDP and providing a factory-stated 20 percent reduction in force required to rack the slide. My own measurements averaged a 22 percent reduction compared to a standard PDP Compact. There was also a noticeable difference between the two guns when it came to depressing the bilateral 2″-long slide locks, with the F-Series being decidedly easier to release. This is still a recoil-operated gun, one that digested 400 rounds through two different models, but the amount of effort required to rack the slide and release the slide lock is greatly reduced by not having to overcome the weight of the striker spring as part of the cocking cycle.

The trigger’s shape was re-designed and moved backward 0.29″ where the finger engages its face. It pivots at the same point as the PDP, but has been re-contoured to be easier to reach with small hands. It has a blade safety in its front face, and it broke crisply at a 4-lb., 12-oz., average with a short positive reset. A coil trigger-return spring moves the trigger back into firing position with a positive click. Depressing the trigger moves the trigger bar in the frame’s inside right side, pushing up a tab to clear the passive firing pin safety then releasing the striker to go forward and strike the primer of a chambered round.

Barrel lengths are either 4″ or 3.5″, and the former was used for accuracy testing. The steel guide rod is surrounded by dual recoil springs on the 3.5″, while a flat-wire coil spring is used on the 4″.

When it comes to the metal parts, particularly the slide and barrel, they are machined on CNC machines by Walther in Ulm, Germany, Tenifer-treated and then blued over the Tenifer.

Some commented that the F-Series guns, like all PDPs, are visually top-heavy. In the hand, it does not feel so. That is due to the three, deep cocking serrations on the slide’s rear and three forward of the ejection port, called “SuperTerrain” by Walther. They are 0.196″ wide, taper downward, are well radiused and are very effective in gripping the slide. Those serrations extend up into the cover plate for the mounting of an MRD with Walther’s Gen2 optics cut. One plate of the owner’s choice will be supplied via after-purchase voucher.

Although the slides and barrels are machined in Germany, the gun is assembled with the remaining U.S.-made parts at Walther Arms in Fort Smith, Ark.—on a line next to where the PPK and PPK/S are made. In fact, the idea for the F-Series began in Fort Smith—welcome news, no doubt, to the estimated 40 percent of new shooters who are women.

When I visited Carl Walther in Germany last year, I was made aware of the commitment Walther made, under the leadership of Knöbel, to develop a new pistol that really was designed for women. I think Walther on both sides of the Atlantic succeeded. That said, my man card may be in jeopardy as I am neither a woman, nor do I have particularly small hands, but I found myself preferring the F-Series to the PDP Compact in the hand, with only the shortened trigger reach requiring some adjustment. I have no idea what that says about me. And I’m not alone. One decidedly male, 280-lb. staffer liked the F-Series so much that he bought one—for himself. Question his masculinity at your own peril.

Years ago, I guided elk hunters during a late-season hunt in Montana’s Bitterroot Mountains. It snowed constantly, with temperatures hovering around minus 20 degrees Fahrenheit. One of the hunters carried a semi-auto hunting rifle chambered in .30-06 Springfield. Snow would get into the rifle’s action and freeze up. Every time we set up to watch a meadow or felt like we were closing in on the author of a set of fresh tracks, we’d chamber a round in preparation for a shot.

I’d have to dig out my Leatherman tool and use it as a hammer to pound the semi-auto’s “bolt” rearward, breaking the ice and forcing the action open to chamber a round. I had to repeat the process to clear the chamber. It was dangerous, and a terrible way to treat a nice rifle. Additionally, the ice effectively converted the semi-auto rifle into a “one-shooter.” The bolt-action rifles in camp would ice up as well, but thanks to their design, still functioned, though stiffly.

Conditions like those are tough on rifles. Cold, snow, dust, ice, heat and mud all adversely affect rifles. Here are five tips to help you keep your hunting rifle functioning during a hardcore hunt in tough conditions.

1. Tape Your Muzzle: Keeping the inside of your barrel clean and free of moisture, dirt and debris can be critical to the success of your hunt and the health of your rifle. Several years ago, I was guiding a fellow on a limited-entry bull elk hunt in Utah. It had taken him almost a quarter-century to draw the tag, and he really wanted a big bull. We’d followed a herd of elk through pinion and juniper timber for some time before they stopped in a little canyon, and we readied for a shot in case the bull we were hunting showed himself. When the hunter tried to chamber a round, the bolt wouldn’t close. Forty-five minutes of wilderness gunsmithing later we finally managed to dislodge and remove a tiny piece of bark that had been snagged in the ports of the rifle’s muzzle brake, slid down the barrel (the rifle was carried muzzle up via a shoulder sling) and lodged against the shoulder of the chamber, making it impossible to chamber a round. Thankfully the big bull hadn’t shown himself, but if he had, we would have been up the creek without a paddle. It was a good lesson on the importance of keeping your muzzle protected.

Keeping water out of your bore is the most common reason to tape up. Not only can it cause rust, if water droplets build up in the bore and then a shot is fired the moisture can block the bore and cause excessive pressure.

My favorite way to cover the muzzle of my rifle is with electrical tape. Put one layer across the muzzle and reaching ¾ inches down each side. Unspool another six inches and wrap it cleanly around the barrel an inch or two behind the muzzle to serve as extra tape. Once you’ve shot and the tape is blown off the front, just clear the remnants and replace with a section of your extra tape.

Another great method is to use a tiny balloon. Simply pull the balloon over the muzzle, where it should fit tightly around the outside of the barrel. This method will serve better on any rifle with a muzzle brake.

The question always arises: Will taping/covering my muzzle adversely effect accuracy? The answer is no. I’ve shot many animals with my muzzle taped and never had a shot go astray. That said, if I were preparing for a long-range shot, say beyond 400 yards, I would remove the tape before shooting if time allowed.

2. Deal With Dirt: Many of the west’s greatest hunting opportunities, as well as a majority of African hunting, occurs in arid, dusty environments. Your rifle will inevitably become permeated with dust, regardless of how hard you try to protect it. Dust won’t harm your rifle and is easily wiped away after your hunt, so long as you follow good dust-country protocol.

When hunting in a dusty environment, carefully wipe away any oil on your rifle. This includes inside the bore, and is especially important on all moving parts. Any surface oil will collect dirt and dust, turn to mud and act as an abrasive, causing rapid and excessive wear. In drastic cases, the mud can clog the action on your rifle and render it unusable until you administer a thorough cleaning. When wiping your rifle down, don’t use any solvent or cleaner; you want the pores of the metal to retain enough oil to keep it healthy.

3. Cope With Cold: The biggest trouble cold temperatures might cause is freezing up your rifle, like what happened to the hunter in the beginning of this article. There are two main ways it happens: First, ice builds up in the action. This is usually not a huge problem for a quality bolt-action hunting rifle. Second, oil can congeal in the action making it stiff, and if oil congeals around the firing pin, it can fail to strike, resulting in a misfire. The only way to solve the issue is to remove the bolt, warm it well, and disassemble and wipe the inside of the bolt and the firing pin free of oil.

When you’re preparing for a cold-weather hunt, take the time beforehand to disassemble and wipe the oil out of your action and firing pin assembly. Replace it, if you wish, with non-congealing oil. My preference is to leave it dry, and then disassemble, clean and oil it nicely after the hunt is over.

Condensation can be a problem on cold-weather hunts. Rifles brought in from the cold, especially into a heated wall tent or similar, will rapidly gather moisture and non-stainless rifles may rust surprisingly fast. The best cure for this problem is to leave your rifle outside in a sheltered place during the night. Don’t do this, obviously, during a polar bear hunt. Better a rusty rifle than a fat polar bear.

4. Prevent Corrosion: The hardest use I’ve ever seen rifles endure was in a brown bear camp on the Alaskan Peninsula, where I’d gone in pursuit of a story and, accidentally, agreed to work as a packer. Several of the guides had stainless Ruger Model 77 rifles that they used as backup rifles, walking sticks and anything else that came to mind, even as a staff braced against the stream bottom when crossing rushing rivers.

Taj Shoemaker, one of the guides, had performed a rust-preventative test using a broad assortment of oils and protective agents including Rem Oil, WD-40, Kroil, Corrosion-X and more. He treated matching pieces of metal with the different agents, labeled them, and laid them out in the brutal Alaskan Peninsula weather for months, observing and keeping a record of rust progression. Corrosion-X proved to provide the best protection by a significant margin. At his recommendation I dampened some shop towels with the agent, sealed them in a zip-lock, and used them regularly to wipe down my blued Winchester 1886. It worked wonderfully, and I highly recommend doing the same if you will be hunting in a truly wet, corrosive environment.

5. Scope Maintenance: Riflescopes don’t need a ton of care, and honestly, the best preventative measure you can take is to invest in a high-quality optic. Better to spend a few hundred extra now than to shed bitter tears after a huge buck or bull is lost due to a scope that lost its zero or fogged up at the moment of truth. Heat, cold, dirt, water, ice, bumps and jolts, and a generally rough lifestyle is the lot of a hardcore hunter’s scope, and an expensive, high-quality optic will weather the storm much better than a cheap version.

Things you can do to protect and care for your riflescope include keeping a neoprene scope cover on it, wiping the body and turrets clean on a regular basis, and exercising care when cleaning the lenses. Many hunters will simply rub a dirty sleeve across their dusty lenses every once in a while. This does more harm than good, grinding abrasive dirt and dust from both the lens surface and the sleeve into the glass, scratching and wearing away the lens coatings. Instead, use your breath to blow away large particles, then use lens cleaning solution and a soft lens cloth to gently coax away remaining dirt and grime.

If your rifle takes a fall or bumps hard into something, examine the setup, especially the scope, for damage. You may need to re-zero; because more than likely your scope has been nocked off, especially if there is a visible mark or damage to the scope’s exterior. For that reason, I always carry 10 or 15 extra cartridges in my pack.

Conclusion

If you follow the guidelines above, your rifle will stand strong though almost anything a hardcore hunt throws at it. When the big buck or bull of your dreams offers a shot, it’ll be ready and so will you. Remember to thoroughly clean and lightly oil the rifle after the season is over. If you’ve removed or substituted oil during a particularly dusty or cold hunt, take the rifle apart, clean other agents away and lightly oil with a quality firearm oil. Then store it on a clean place. It’ll be ready and waiting when the season rolls around again, and your next adventure awaits.

Britain Stands Alone

Between May 26 and June 4, 1940, more than 330,000 British, French, Belgian, Dutch, and Polish troops were evacuated from the beaches at Dunkirk. By June 25th, another 190,000 troops (more than 140,000 of them British) were evacuated to England from French ports. Unfortunately for the British Expeditionary Force, they left their heavy weapons and vehicles behind. Most of the troops who made it to England arrived with just the uniforms on their backs, their rifles and machine guns having been abandoned in France.

With France conquered, the Germans began bombing England in earnest by the middle of July. Initial attacks were on merchant shipping in the Channel, followed by ever increasing raids on British radar installations and RAF fighter fields across southeastern England. As more and more German aircraft appeared over the British Isles, the prospect of a Nazi invasion seemed more likely every day, particularly an aerial assault by German paratroops. By the end of the first week in September, hundreds of German bombers were attacking London by day and night. England was in grave danger.

Help From America

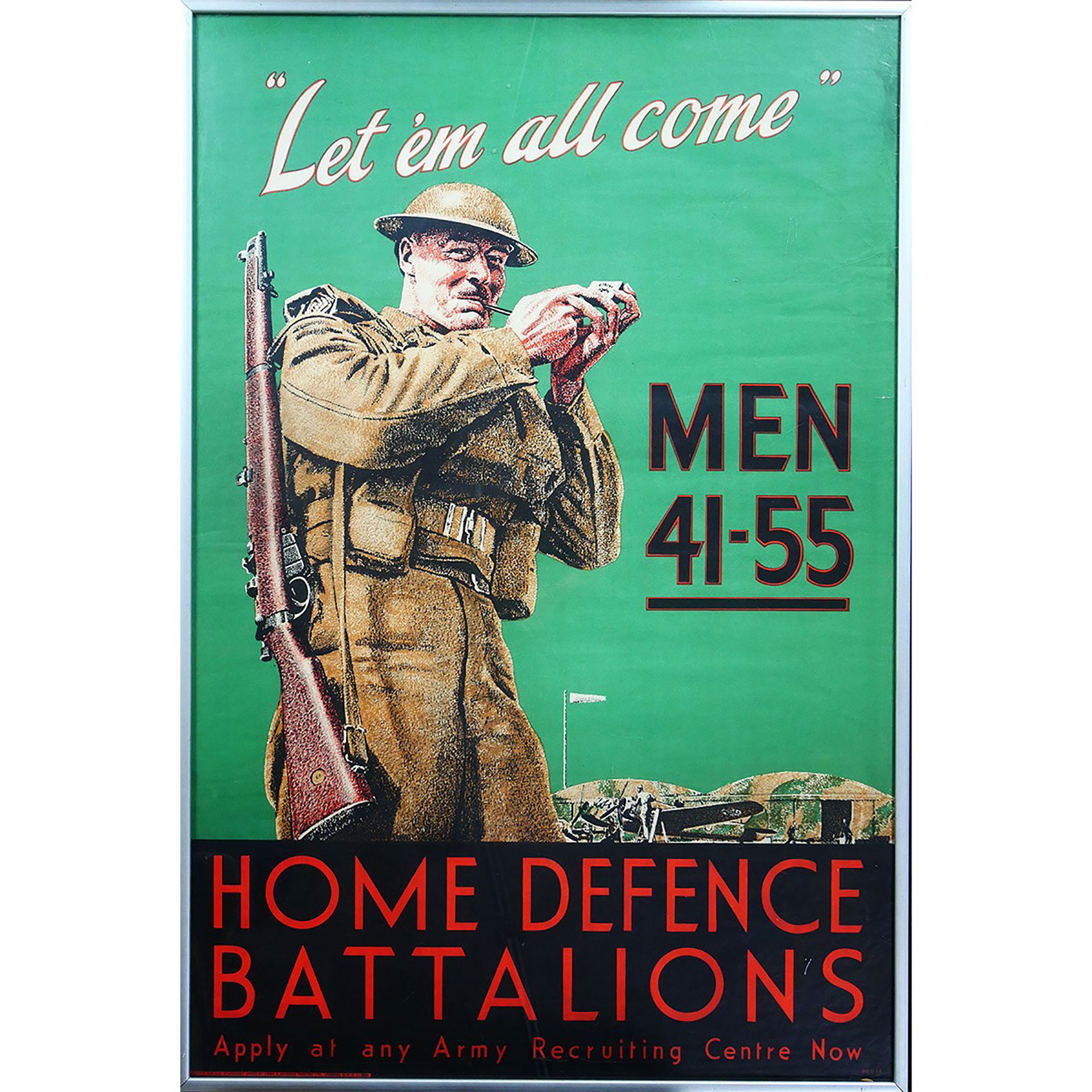

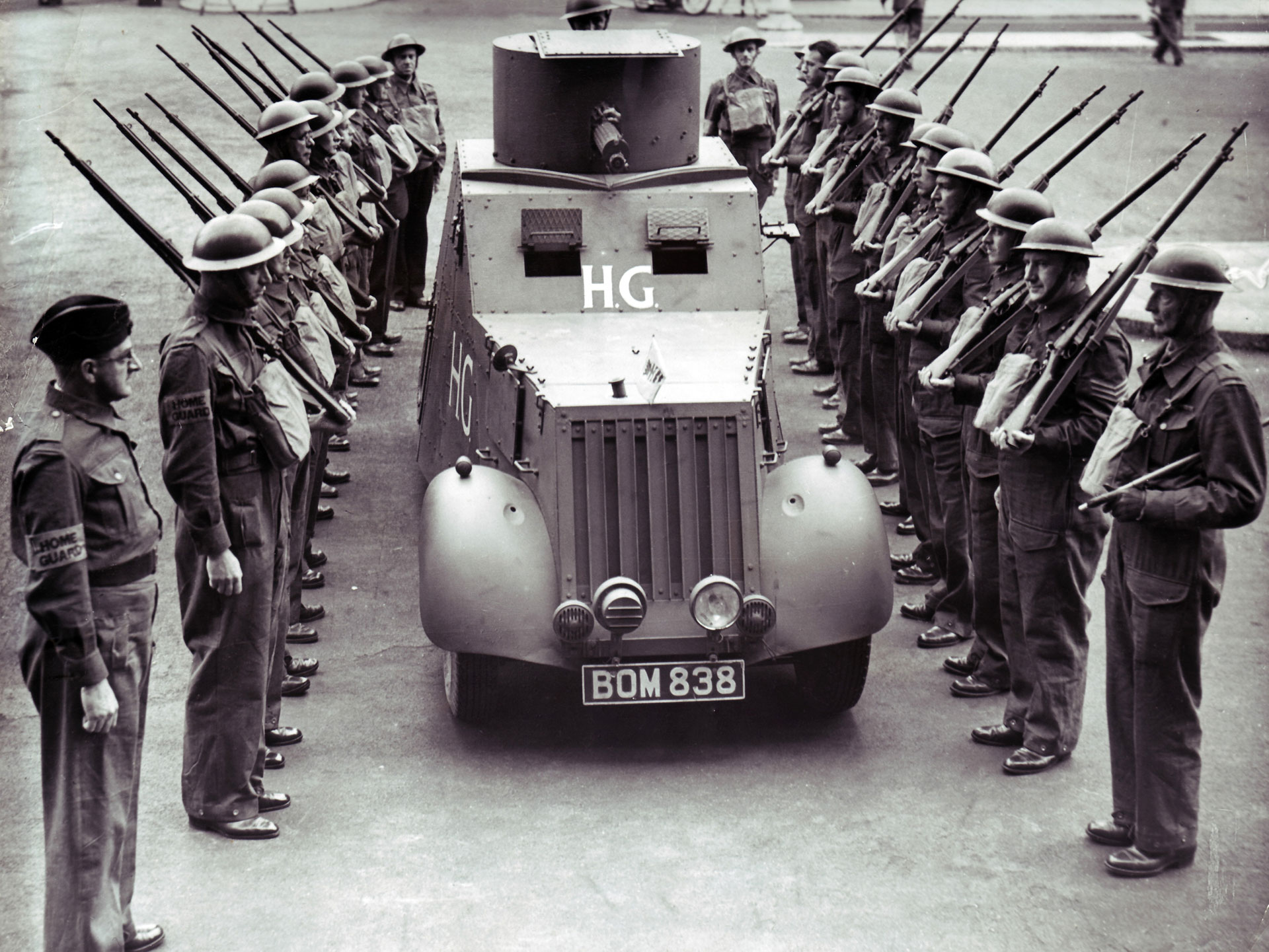

While RAF fighters struggled to defend their airspace, the British Home Guard did their best to mobilize a legitimate militia to help defend against a German invasion. Small arms were particularly scarce. There was no lack of volunteers, but unarmed free men would do little to stop well-armed Nazi wolves at the door. America, though still neutral, was quick to help. By the autumn of 1940, the American Committee for the Defense of British Homes was formed (with key organizational assistance from many NRA members).

Appeals were presented to American citizens in many publications (including, of course, American Rifleman magazine) to help the British defend themselves. Pistols, rifles, shotguns, and binoculars were collected from generous Americans and shipped to England. In December 1940, President Roosevelt described the concept of turning America into The Arsenal of Democracy. On March 11, 1941, the critical Lend-Lease Act was signed into law, and arms began to flow from America to England. Winston Churchill later wrote: “By the end of July 1941, we were an armed nation.”

A wide range of US military firearms were sent to England, predominately for use with the Home Guard. The biggest challenge for the British was that most of these arms were chambered in .30-’06 Sprg., or in .45 ACP.

The M1917 .45-cal. Revolver: The British Army had adopted the M1917 revolver during World War I, and many remained in British stocks. More came over in Lend-Lease, and these were used by the Home Guard and also by the Royal Navy.

The M1917 & P14 Rifles: During 1940-1941, the British acquired 734,000 of the “United States Rifle, Caliber .30, Model of 1917“. These were marked with a highly visible red stripe painted on the fore-end of the stock to distinguish between the American M1917 and the British P14 chambered in .303 Brit.

The Browning M1917 Machine Gun & The Colt-Vickers M1915 Machine Gun: The Browning M1917 .30-cal. water-cooled machine gun was supplied to England during the early days of Lend-Lease, with about 650 guns going directly to the Home Guard. The US Colt-Vickers M1915 was of more value to the Home Guard, as it differed only in caliber from the standard British heavy machine gun. Approximately 7,000 M1915 MGs were provided to the Home Guard and served until they were destroyed post-war.

The Browning Automatic Rifle: The British were quite impressed with the BAR, and they strongly considered the weapon (in .303) until 1930, when they decided to move forward with the Bren Gun design. After the BEF abandoned most of their heavy weapons in France during late May 1940, there were only about 3,000 Bren Guns left in England (almost 27,000 having been lost in France). To compensate, the British acquired about 25,000 BARs, and these served the Home Guard until the end of the war. There was much concern in England about Home Guard BAR gunners “wasting ammunition” by using the weapon set for full-auto fire. After 1943, the Home Guard was instructed to use the BAR strictly in the semi-automatic mode.

The Thompson Submachine Gun: The Thompson submachine gun was the most numerous American-made firearm supplied to the Home Guard, and ultimately to British forces throughout the war. The “Tommy Gun” made a huge impression on the British, from Prime Minister Winston Churchill to the man on the street and boys in the schoolyard. Even before Lend Lease in March 1941, the British had purchased 108,000 M1928 Thompson Guns from Auto Ordnance. By the end of the war, America sent a little more than 650,000 Thompson Guns (of all models) to England.

The Home Guard Remembered

It is difficult for us to understand now the precarious situation in Britain was in then. As a researcher, I can work to uncover the details about firearms sent and used. I can write about strategy and tactics. But I wasn’t there, and I don’t know how it felt. In that light, I was fortunate to have a friend who lived through the Battle of Britain as a pre-teen boy. I asked Gerry Marsh if he would share his memories of those days and his observations of the Home Guard in his community.

I recall listening to a radio broadcast encouraging those able to join a defense group to do so, to report to their local police station and sign up for duty. I recall, too, for the figures are lodged in my head with pride, the government fully expected half a million men and women to sign up. In fact, 1.7 million volunteered. What did they get for that? Eventually they received a uniform, even later a rifle, along with hours of arduous duty without pay, and the undying gratitude of a whole nation for men and women torn from their placid lives and pressed into service in a national emergency.

The group I watched was one of the many that sprang up quickly and spontaneously, inspired by other patriotic groups that had gathered themselves in anticipation of invasion. They would morph into the Home Guard when that body was approved by, and subject to the rules of, the Home Secretary. The group I saw was all male, for women did not join them until the Home Guard was approved and regulated by Whitehall’s Home Office.

Many of the volunteers in my group, particularly the older ones, must have wearied at the thought of new danger, a renewal of a hell they thought was over. World War One had ended only twenty-nine years before, in 1918. It was still fresh in their minds and in the minds of my parents and grandparents. I thought then, and I think now, that World War I and World War II were for all practical purposes one war with a short tea break.

The playground, or the Bullring as we called it, was solidly edged with subsidized housing, or what we called council houses, built close together, surrounding the playground unbroken, save for three narrow entrances. On the playground was a roundabout and a quadruple set of swings. The paint on them had worn off years ago. The ground was hard packed and stony and bearing occasional stretches of determined grass. It was on one of these patches that the Home Guard assembled for training.

The men wore ordinary clothes. A few were in the suits they wore to their offices in town, others wore work clothes suitable for their jobs in a butcher’s shop or the barber’s, while many of those who worked on the land wore rough linen shirts without collars, heavy muddy Wellington boots and baggy pants of a hard wearing material, none-too-clean, tied up just above the knee with a bit of frayed string. There was a little laughter, but not much; this was a serious business. Any time, today, tomorrow, or who knows when, German Junkers Ju-52s could fill the skies and drop heavily armed parachutists in our midst.

These men, who should have been at home before a coal fire, reading the Daily Mail and looking forward to dinner were instead out on this cold night, ready to defend their country. They were in a serious mood, occasionally jocular in the British manner, but they were there to learn. There was no telling when they might need the deadly skills they were taught.

Several of the men, farmers from around Chester, had shotguns. Three or four of the men had Enfield bolt-action rifles left over from WWI. Three or four had ancient pistols, guns they were apparently allowed to keep when World War I ended. An unfortunate few had only broomhandles sawn down to shotgun size. They all wore armbands, brown bits of cloth on the left upper arm bearing black letters. The early groups called themselves different things, “D.F.” for Defense Force, “P.A.” for People’s Army, and similar names until the government set about organizing them. The man in charge had sewn on just above just below his armband, a design of three V-stripes denoting his rank as Sergeant.

I cannot remember exactly what the Sergeant said; I recall only that he stressed upon them the importance of what they were doing and told them he had every hope that the government would be able to furnish them all with uniforms and guns in the future. Rifles were slow in coming. I remember that later, to compensate for the paucity of guns and ammo, they were taught how to make improvised hand grenades and Molotov cocktails.

I think that they trained four nights a week. It was not their only chore. Later in the evening, when it was dark, I would see some of those same men, in pairs, patrolling the streets, doing double duty, this time wearing a different band on their sleeve, “A.R.P.” or Air Raid Precautions. Their job was to make sure all lights were hidden by drawn blackout curtains. People walking in the street were told to put out cigarettes with the unlikely warning that Luftwaffe pilots could see the end of a lighted cigarette from six thousand feet up.

If there was a raid, the HG or ARP men were to douse incendiary bombs if possible, as they were likely to be on the spot more quickly than the fire brigade. On occasion, they would run to the site of a downed enemy plane, rescue the pilot if they could, strip him of weapons and tun him over to the police. Or perhaps kill him.

The End Of The Beginning

The Luftwaffe Blitz on British cities lasted from Sept. 7, 1940 until May 11, 1941. More than 40,000 British civilians were killed, and approximately 2 million homes were destroyed. London was devastated, but England survived. Winston Churchill had commented “We can take it”, and indeed the British could. Grit and sacrifice had seen them through the darkest days. Fears of a German invasion started to fade, and after America entered the war in December 1941, a “friendly invasion” of American troops began soon after.

S&W J Frames anyone?