Author: Grumpy

A good Cop Story for you!

Free Form Friday – Death is Easy; Duty is Hard

Sorry for the prolonged absence. Work’s been busy. But banking that sweet sweet over time so as to bring y’all more quality gun content. And I’ve been devoting a lot of online time towards pushing various links to download 3d guns. Because don’t tell me what to do. Death to tyrants. Justice for Lavoy.

All that aside; enjoy the following. Bud is a dozen State Troopers I’ve known. He’s some how related to Jim and Jake, just not sure how yet.

The State Patrolman was clad in khaki. Not pressed per say but obviously well tended. He wore a Smith and Wesson Model 27 in a low slung basket weave holster. The holster hung low but not ostentatiously so. It was worn at the location a man who might have to draw in a hurry just as soon as he hopped out of a car might wear his gun. Or by a man who might have to shuck his gun to jump in a rain swollen river after a small child might have to do. Bud Charles had done both. And lived to tell about it. Bud was man who wore a gun to work every day. Actually, we wore three. The Model 27, which he still referred to as the Highway Patrolman because, damn it, Smith and Wesson made good guns with good descriptive names. Damn lawyers. On his left ankle was an airweight Model 642, not quite a Chief’s Special but just as reliable. And with the current collector frenzy of good working guns, Bud couldn’t quite bring himself to actually wear his Chief’s Special on his ankle anymore. But if anyone asked it was because the old Model 36 (those damn numbers again) was a heavy sumbitch with an exposed hammer. The 642 and 27 could share ammo if it came to it. Bud kept six Federal 125 grn .357 JHP in his Model 27.

Yes, the rest of the patrol was carrying a Glock in either .40 S&W (worthless) or in .357 Sig (damn near worthless), but, Bud in his career had been more frequently to put down hurt moose than shoot bad guys and that’s where the old magnum six shooter reigned supreme. He carried three HKS speed load which were loaded with 158 grn .38 Special +P LSWCHP, the old FBI load, which was probably the best damn people stopper this side of 230 grn .45 ACP or that new fangled 10mm Buffalo Bore stuff. Sidenote, Bud, when having consumed a beer or eight, would go on at length how the 10mm was the best pistol cartridge ever, how the S&W 1076 was the best duty pistol ever, with apologies to John Browning, and how those damn women FBI agents should have just been given old Model 15s if they couldn’t handle the 1076. He also would go on and say that he would probably be called Stumpy before too long because of how much fun the 10mm was to reload for. A face full of Glock parts would be totally worth it for 2,000 FPS out of an autoloading handgun in a real cartridge. Oh, yeah, his third gun. His jesus gun. His “shit if I ever use this things are bad” and also “damn, it came down to me using a Glock” gun. He stuck a Glock 43 in his vest. If he was in a fight, shot both his wheel guns dry, what have you, he could get the itty bitty Glock out and have seven rounds of .380 ACP to make a last stand of it with. Bud considered the .380 ACP about useless, but hell, putting a small fast bullet in somebodies belly might make them reconsider bashing his skull in or something.

So those were the three guns that Bud carried. He had carried an M-9 Beretta in the Army as an MP (hated it) and carried a M-1911A1(loved it) as a National Guard MP. Until he deployed to the Sandbox after 9/11. He then carried an M-11. Which, for a 9mm autoloader wasn’t terrible. He also used to great effect on a couple of supposedly friendly a Benelli auto loading 12 gauge. Which damn, did thing end a fight in a hurry.

Which brings us to our present situation.

Bud’s khaki shirt was covered in mud and blood. His 642 was dry. His Model 27 had no shit been shot out his hand by the jihadi fuck with an AK clone inside the school. The fucking local cops, more used to giving tickets to passing motorists than real police work, had fled. Things were pretty damn bad for Bud. A beer seemed really damn good right now. But hell, it was only 11 o’clock in the morning on a Tuesday. His Dad, a legend on the Patrol had served with a man who had policed the state with old Captain Dillard, who might have been the meanest sumbitch to ever wear a star on his chest and the big hat. Somewhere deep down in Bud, something called duty rose up. He took off his tie and bandaged his hand. Thankfully, it was his right hand, which he could still use his trigger finger and not fuck up what he had to do next. After bandaging his hand, he fished out his jesus gun. Seven rounds of .380 were sent pretty damn quickly towards the main door way of the small school. Bud rolled out from his concealment behind the bushed. Beating feet to his cruiser he yanked the Mossberg M590 out from its dash rack. He dumped two boxes of double ought buck in his pockets, hoping it wouldn’t come to that because of all the kids. He quickly worked the pump to eject the eight rounds of buck out and threaded in 8 slugs. Big .67 caliber chunks of lead that fucking ended fights in a blast of brimstone that instantly sent a miscreant to the diety of his choice. More importantly, the Remington Sluggers defeated most body armor, which those damn jihadi bastards seemed to be wearing the way they had taken round after round from the school resource officer’s .40 S&W pistol. Damn, Dennis was dead. Shit, they were going fishing Saturday and Dennis owned the boat. Fucking goat fuckers.

Bud rose from the cover of his cruiser. A jihadi was moving forward with his AK-whatever the fuck torwards him. The big ghost ring sights made the shot easy. The boom from a real mankilling weapon was deafening. But Bud had put on his electronic ear muffs. One dead bad guy for sure. Bud was pretty sure that he had killed one with a .357 JHP to the head earlier. And Dennis was most concise when he said six terrorist had hit his school. Good man, Dennis. That meant the odds were a bit better. Bud had gone up against three men once and lived to tell it. Hell, and the boys from A Barracks and there damn tactarded AR-15s couldn’t be too far away by this point. Bud stepped through the glass door frame. The glass having already been shot away by the Jihadis when they made their entrance. Screams down the main long hall guided him. He took a guess and assumed that the bad guys, after suffering two causalities, would retreat inwards.

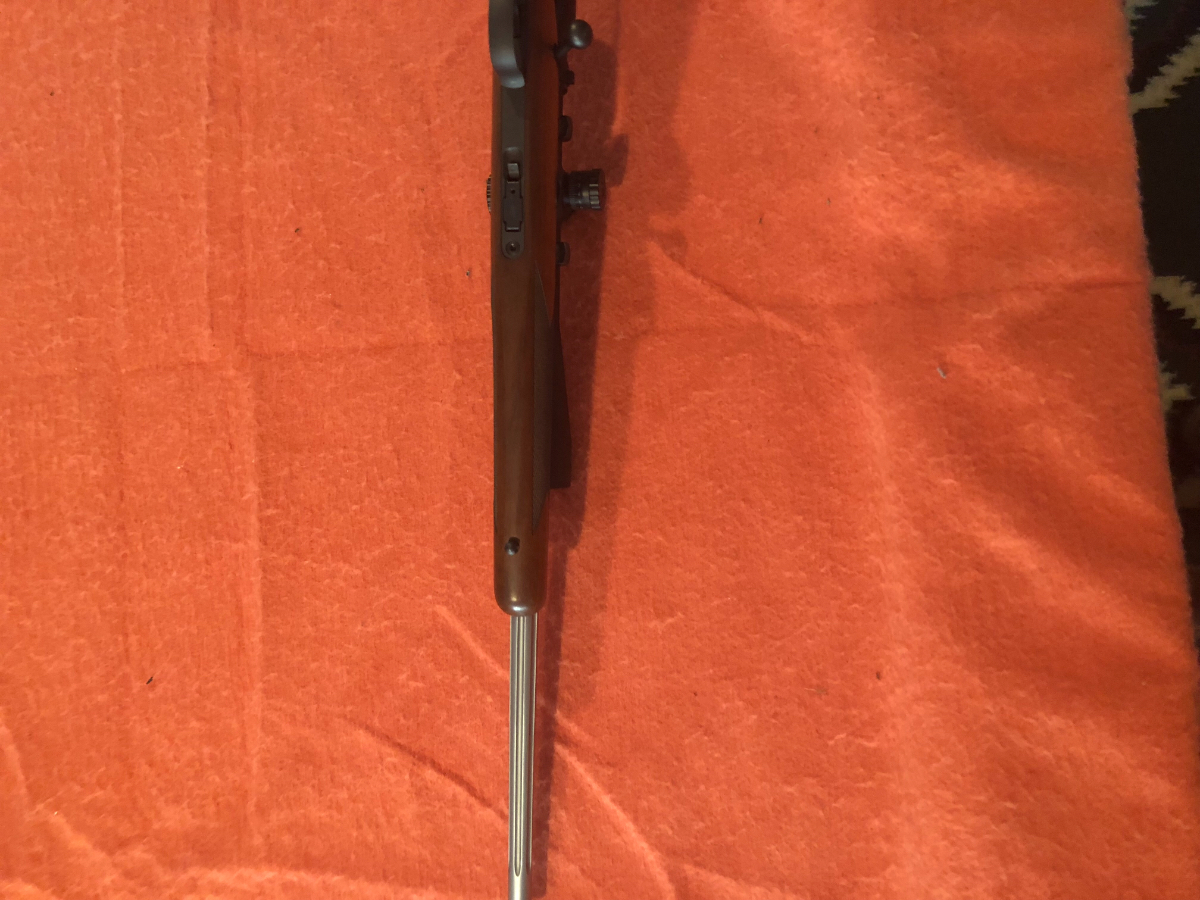

One very strangely cut stock you got there Buddy. But if it works for you. Well Good luck & God Bless!

It does have some wood & grain there though!

But I would change the Scope & Rings though.

Now this is a weird Caliber to these old eyes. But it has some seriously good looking wood for a stock!

While participating in an anti-gun march in Massachusetts over the weekend, gun-control crusader David Hogg posted a hair-raising and head-turning ultimatum to Smith & Wesson.

Hogg told the popular firearms and ammunition manufacturer, headquartered in Springfield, via Twitter, that it had to fund “gun violence prevention research” to the tune of $5 million annually and cease making certain black rifles or else…

Hogg and his posse of moonbat millennials would “destroy” S&W.

“We will destroy you by using the two things you fear most,” wrote Hogg. “Love and economics 🙂 see you soon.”

It didn’t take very long for folks on Twitter to point out the obvious flaw with Hogg’s plan. For a boycott to be effective, the protesters must be active consumers of a company’s products.

What a joke! Hogg stands about as much of a chance of shutting down S&W as PETA does McDonald’s.

A spring snowstorm was bearing down on the remote mountain town of Kettenpom when Norma and Jim Gund received an unexpected call from the Trinity County Sheriff’s Office.

The Gunds’ neighbor, Kristine Constantino, had dialed 911 from her cabin five hours northwest of Sacramento and hung up. The closest deputy was en route from the county seat of Weaverville, 97 miles away. But the drive — through rugged forest and over steep passes — would take almost three hours.

The Gunds said the sheriff’s office asked if they could check on their neighbor in the meantime. They were happy to oblige.

As the afternoon slid into evening, Jim, then 59, and Norma, 49, drove their blue Ford pickup to Constantino’s house, a quarter-mile down a dirt road.

Norma approached the house while Jim stayed in the truck. Before she reached the front door, a man met her outside and told her Constantino was fine.

Norma insisted on going in anyway. As she crossed the threshold, she saw Constantino and her boyfriend dead on the floor, their bodies wrapped in plastic.

Then an excruciating jolt surged through her body. She later would learn she had been hit with a stun gun. But in the moment, Norma knew only that her muscles were contracting and her legs were buckling. She fell to the floor and the man jumped on top of her, slashing her face and throat with a hunting knife.

Entering the house to check on his wife, Jim saw the stranger holding Norma down, bloody blade in hand.

“Run, Norma! Run!” Jim shouted as the man turned the attack on him.

Too few deputies

As urban areas such as San Francisco, Los Angeles, Sacramento and Fresno grapple with discussions about use of force and the over-policing of minority communities, the state’s rural counties face a growing and no-less-serious law enforcement crisis: a severe shortage of staff that puts the public — and deputies — in danger.

A McClatchy investigation found that large stretches of rural California — where county sheriffs are the predominant law enforcement agencies and towns often run only a few blocks — do not have enough sworn deputies to provide adequate public safety for the communities they serve.

Departments in multiple jurisdictions are operating with skeleton staffs, McClatchy found, pushing response times into hours, or sometimes leaving residents without a response at all. In Trinity County, deputies regularly cover hundreds of miles of territory alone, leaving people like the Gunds to fend for themselves. When law enforcement does arrive in many outlying places, it’s often a single officer cut off from backup and, in some cases, communication with her or his department.

“We have no money. We have no people,” said Modoc County Sheriff Mike Poindexter, echoing more than a dozen rural California sheriffs. “We don’t have near enough people. We just don’t.”

McClatchy interviewed law enforcement and residents in 20 counties and examined staffing levels and crime statistics in 25 counties identified as rural by the California Communities Program, a rural-affairs center run by the University of California.

These counties account for 41 percent of the state’s land but 4 percent of its population. They include tourist destinations such as the Mendocino coast and Yosemite National Park, as well as some regions that are so inaccessible they require horses, snowmobiles or boats to reach.

Data analysis showed the number of sworn deputies in these rural California counties has dropped by 8 percent in the last decade, when sheriff’s department staffing in urban counties declined by only 2 percent.

In 2008, 1,758 sworn deputies worked in rural counties, according to the California Department of Justice. By 2017, that number had dropped to 1,610. The decrease may not sound drastic, but the loss of those deputies has pushed some already overworked departments to a tipping point in service, sheriffs and others said.

While the Sacramento County Sheriff’s Department employs nearly 160 deputies for every 100 square miles it covers, the tiny sheriff’s departments in Madera, Mariposa and Mendocino counties employ about four deputies for the same amount of turf. In Del Norte and Alpine, the counties make do with two deputies per 100 square miles.

Those figures include non-patrol personnel and those who work in county jails. Leaving those deputies out, the sparse staffing of rural sheriff’s departments becomes even more striking.

At any given time, for example, the Lake County department has just five deputies patrolling an area the size of Rhode Island. Amador usually deploys three or four deputies over 612 square miles.

“Unless there is a call for service, there are a lot of areas in the county that don’t get patrol coverage,” said Amador County Sheriff Martin Ryan.

In Lake County, where the Mendocino Complex Fire is still burning, a resident calling for aid in its remote reaches might have to wait 90 minutes for a sheriff’s deputy to arrive, “and that’s on a good day,” said Sheriff Brian Martin.

Residents of Mono County, on the eastern slope of the Sierra Nevada, sometimes must wait two hours for a deputy, said Mono Sheriff Ingrid Braun.

On the North Coast in Humboldt County, deputies’ response times can be as long as three hours. In the isolated mountainous areas of Madera County, the wait can stretch to four hours.

In multiple rural counties, not a single deputy actively patrols for certain periods of the day.

“There are deputies at home basically in bed that are subject to call-out if something is happening,” said Greg Van Patten, field services commander at the Mendocino department, where deputies do not patrol for four hours a night.

Many rural Californians interviewed by McClatchy said the lack of nearby law enforcement is frightening.

“We can’t ever just call someone and know that they will be here in a timely manner,” said Janet Irene, who runs the Country Hearth restaurant in the Modoc County town of Cedarville, 20 miles over a mountain pass from the sheriff’s office.

‘Things go on in the hills’

Rural areas often are sparsely populated and historically have had meager law enforcement presence as a result, even including the small police departments that some towns may have in addition to the county sheriff.

But these counties are increasingly grappling with the same problems as their urban counterparts — homelessness, mental illness and drug use and production, including marijuana and opioids. These issues all add strain to the bare-bones departments.

Some counties have high, or higher, crime rates than metropolitan areas.

McClatchy analyzed county-by-county crime data supplied by the California Department of Justice and found the violent crime rate in rural counties was higher overall than elsewhere in the state during 2017 — though it varied significantly by county.

About 4.7 violent crimes took place per 1,000 residents in the 25 rural counties in 2017, compared to 4.5 violent crimes per 1,000 residents in other California counties. Some rural counties — Shasta, Lassen, Inyo, Lake, Modoc, Mariposa, Trinity, Madera, Plumas and Del Norte — have among the highest violent crime rates in the state. Most are also among the poorest counties.

Trinity County, where the Gunds live, had a crime rate of 5.7 violent crimes per 1,000 residents in 2017, higher than the statewide rate, according to the California Department of Justice. The attack on the couple likely was part of a robbery of a marijuana grow that Constantino was managing, according to the Trinity County Sheriff’s Office.

On that day in March 2011, as Jim Gund grappled with the assailant, Norma was able to escape. She drove their truck to the town’s only store for help. The stranger hit Jim nearly two dozen times with the stun gun and slashed him with the knife, but Jim managed to get away as well.

The attacker, later identified as Tomas Gouverneur, 32, fled and died after crashing his car while being pursued by sheriff’s deputies in neighboring Mendocino County.

The Gunds survived the ordeal and filed a lawsuit against Trinity County, claiming they were inappropriately asked to do a deputy’s job.

The Trinity County Sheriff’s Department originally had disputed that it asked them to check on Constantino but later acknowledged it during court testimony. The Gunds’ suit has been unsuccessful for them so far but is headed to the state Supreme Court.

Trinity County Sheriff’s Lt. Christopher Compton declined to discuss the case, citing the litigation. But Compton said renegade pot growing and drug abuse have increased in the county, adding to crime.

“I could say that the challenges are unique to us,” Compton said. “But I don’t know if they really are.”

Doug Binnewies, the sheriff of Mariposa County, said his area has been hit hard by a mental health crisis and suffers from an acute shortage of treatment facilities, a problem that affects crime there.

Rural counties have 0.9 psychiatrists for every 10,000 residents, about half the statewide average, according to California Medical Board data. Mariposa has been experimenting with “tele-doc” video technology to connect jail inmates with mental-health professionals in other counties.

Tex Dowdy, the sheriff-elect of Modoc County, said an influx of transient residents drawn to the low cost of living has made identifying suspects harder for Modoc’s deputies.

“It isn’t the same place where we used to live,” Dowdy said. “You used to recognize the bad guy walking around the street because he was in the paper every week.”

Humboldt County Sheriff William Honsal said patrolling in territory long known for its marijuana growing sometimes means trying to protect citizens who have purposely moved far from civilization and won’t call for help.

“Things go on in the hills all around us that go unreported,” he said. “We know that. Daily. It happens. It’s something that we’ve just gotten used to.

There are shootings that occur in the middle of the night. … We know that there’s kidnappings, we know there are people getting brutalized out in the hills, we know there are people getting robbed.”

In San Joaquin Valley’s farm country, undocumented immigrants fearful of arrest are sometimes reluctant to report crimes and present another growing challenge, said Madera County Sheriff Jay Varney.

“They’re kind of underneath the fear that if they have contact with law enforcement, they’re going to be immediately deported back to whatever country they came from,” said Varney as he cruised past an almond orchard.

Until recent years, many rural departments had regional substations and hired “resident deputies” who lived in the remote areas they served.

Those resident deputies knew their territories and most of the locals by name, making it harder for crime to go unnoticed, said multiple sheriffs. Resident deputies also allowed for quicker response times.

Those in need “just come and knock on your door,” said Modoc’s Poindexter. “You just grab your gun belt and go out the door and try to fix it.”

Budget cuts have eliminated most of those positions.

State policy also has increased the strain, sheriffs said. Gov. Jerry Brown’s 2010 prison realignment program, adopted in response to massive state budget deficits and a court-ordered crackdown on prison overcrowding, has dramatically altered how criminals are housed.

Thousands of low-level felons have been shifted from state prison to county jails.

Proposition 47, passed in 2014, also reduced some nonviolent crimes from felonies to misdemeanors. At the county level, some sheriffs and deputies claimed the changes have curtailed arrests and created a revolving-door effect in the jail system, in which inmates are quickly put back on the streets — or never brought in — to allow space for those serving longer sentences.

Multiple deputies said they felt discouraged by realignment and had stopped arresting people for low-level offenses such as drug possession.

On a weekday in Lake County a few months ago, veteran Deputy Dennis Keithly drove his Ford SUV patrol vehicle with his drug-sniffing yellow lab Dozer. His 12-hour shift covered hundreds of miles.

As he was driving past a vineyard near the county seat of Lakeport, he stopped to talk to two men standing by a car on the side of the road.

Keithly asked one of the men, who identified himself as “Bill,” to tilt his head back. Bill’s eyelids began fluttering, a likely sign of methamphetamine use, the deputy said. Keithly gave Bill a quick lecture on the dangers of meth — “You’re going to be dead in your 50s if you keep doing that” — and searched the car for drug paraphernalia. He didn’t find any. He returned to his vehicle and pressed on.

Keithly reasoned the men weren’t worth more effort, much less looking for a reason to arrest them.

“He’s going to be cut loose in three hours,” the veteran deputy said. “It would be a waste of my time, his time, the jail’s time.”

Slow economic recovery

Multiple sheriffs said the shortage of deputies is a simple money issue. Most rural counties are poor and lack an economic base despite the state’s current boom.

Huge pockets of Northern California struggled with the demise of the timber industry in the 1990s, and hardships in farming and commercial fishing.

They have failed to completely recover from the Great Recession even as urban and coastal areas once again thrive. Main streets in rural towns are pockmarked with empty shops, and tax revenue has languished or diminished, leaving local governments without money to pay for public services.

Counties where homes have been lost to wildfires are especially hard hit. More than 1,000 homes were lost in the recent Carr Fire in Redding. Lake County — where the largest wildfire in state history, the Mendocino Complex Fire, currently is burning — has lost about 1,785 homes to a series of wildfires since 2015, eroding property taxes.

Rural economies also are constrained by their vast quantities of protected federal and state lands — forests, parks, preserves and military bases among them — off limits for development and those resulting property taxes.

Counties receive “payments in lieu of taxes” from the U.S. government and the state, but Poindexter, the Modoc sheriff, said the funding doesn’t fully compensate for the lost revenue. That funding also has been unpredictable and is intended for a variety of public services, not just law enforcement.

On the federal level, the funding totaled $60.4 million in California this budget year. Trinity County, with 1.6 million acres of protected federal land, received $1.4 million. Modoc received $1.2 million.

But those amounts are expected to decrease in the next budget cycle as federal funding changes. That leaves sheriffs uncertain about how much money they can expect in the future.

“You can’t sustain an operating budget not knowing what is coming,” said Justin Caporusso, vice president of external affairs at the Rural County Representatives of California, an advocacy group.

The state compensates counties for protected lands, too, but that funding has been controversial and even less predictable. Since the 2015-2016 budget cycle, the state has given rural counties $644,000 for payments in total each year to be divided among them, said state Sen. Mike McGuire, whose coastal district spans seven counties from Marin to the Oregon border.

But the state says the payments are voluntary and didn’t make any for more than a decade before that.

Brown vetoed a 2016 bill by McGuire that would have made the payments mandatory but promised to continue them during his administration. McGuire plans on bringing legislation again in a fourth attempt to make the payments permanent.

“Small communities in rural counties desperately need these dollars to keep their neighborhoods safe,” McGuire said.

McGuire said that even though the amount is a “drop in the bucket” for urban areas, it’s vital in poor counties. Lake County, in his district, received $7,920 from the state funds this year — enough to pay for the county’s subscription to the federal emergency alert system, he said.

Sheriffs said one of the biggest hurdles with inconsistent funding is that it forces them to pay poorly in comparison to urban departments and to offer fewer benefits, making recruitment and retention difficult.

In Lake County, the roster of sworn deputies has fallen from 77 in 2003 to 65 today. (Sworn deputies carry firearms.) Starting pay is $25 an hour, compared to $36 an hour in Napa, just two hours away.

“We recruit at the academies, but we just can’t compete with the other counties,” said Capt. Kevin Jones of the Lassen Sheriff’s Office.

Modoc’s sheriff offers $13 an hour to rookie deputies.

“We get someone else’s reject that either didn’t make it off probation or didn’t make it off field training, and so we, for lack of anybody else, we take them and try to fix the problems they had,” Poindexter said. “Sometimes we hit a home run, sometimes we don’t.”

Different policing, different expectations

The lack of deputies has left both those with badges and those they serve with tempered expectations of what law enforcement can do.

“In a big city, you have backup that’s right there,” said Braun, the Mono sheriff, who previously was a Los Angeles police lieutenant. “In a rural area, you don’t. You learn how to do things on your own, or you wait for backup. It can be challenging.”

Many sheriffs said they rely heavily on help from state and federal agencies including the California Highway Patrol and the National Park Service.

In Cedarville in Modoc, investigative news reporter Jean Bilodeaux recalled when someone fired a gun at her while she was in her front yard after she published a controversial story about the local hospital. Her 911 call took nearly an hour to answer — and then it was a park ranger who arrived.

As departments adapt to handle the changing demographics and dangers in their counties, the problem may grow worse.

On a recent June afternoon in another part of Modoc, Deputy Justin Ridgeway and Sgt. Mike Main drove nearly two hours to investigate a disturbance call in the Ranchettes, a wooded warren of dirt lanes, trailers and junk-filled yards that once was meant to be an upscale retirement community. Deputies don’t regularly patrol it.

“At some point, we let it get away from us,” Dowdy, the sheriff-elect, said.

A few years ago, a deputy would have gone alone into places like the Ranchettes. Now, after a deputy was fatally shot in an ambush in 2016 while responding solo to a domestic violence call, they try to go in pairs, even if it means longer wait times for other callers.

The call the deputies were answering that day stemmed from a woman who had complained that another resident, Damien Roberts, had threatened her after she told him he was driving too fast.

The deputies found what they described as an illegal pot grow at Roberts’ trailer and encountered Roberts driving about five miles away.

A tall man with a heavy beard, he was irate when deputies pulled him over and asked him to step out of his truck. He yelled and waved his arms above his head, arguing the 911 caller had threatened his companion. Alone, it could have felt threatening for a deputy.

Ridgeway and Main remained nonchalant. Ridgeway told Roberts to stay away from the neighbors — and said he had given Roberts’ neighbors the same warning. The deputies didn’t bring up the illegal marijuana, deciding instead to return with re-enforcements.

Roberts, who said he’d had other altercations with police, calmed down and shook Ridgeway’s hand.

“We have freedom with responsibility out here,” Roberts told a McClatchy reporter. “We can do a lot of stuff. These guys referee.”

On the two-hour trip back to the station, Main said he didn’t know if he had done enough to intervene or if the dispute would escalate. But “verbal judo” was the best he could do without more backup. He said the first lesson he teaches new deputies is sometimes it’s best to walk away.

“We’ve got to be smarter,” he said. “I know that there is a hell of a lot of stuff where I’d feel a lot more comfortable going to a call with (more) people rather than just my lonesome.

There’s Tombstone courage where you get yourself into a situation where you’ve bit off more than you can chew and it might get you killed. … If your Spidey senses are telling you something is about to get real, get the hell out of there, especially if you are by yourself.”

How we reported this story: Four McClatchy journalists set out last December to answer a question — how effective is rural law enforcement in California? Starting with a list of 25 rural counties, as defined by a University of California policy center, they assembled a set of databases to compare crime rates and law-enforcement staffing levels with the state’s urban counties. They then interviewed sheriffs, deputies and residents in 20 counties, by phone or in person. They also spent hours in patrol cars in Lake, Mono, Madera and Modoc counties and traveled to Kettenpom in Trinity County to meet with assault victims Norma and Jim Gund.

*********************************************

And the folks down in Sacramento really don’t care. As they are generally Republican & Poor to boot! So if I lived up in that really nice looking area. I would think long & hard about packing some sort of weapon on me & my loved ones. – Grumpy

New Study: 17.25 million concealed handgun permits, biggest increases for women and minorities

Despite the expectations of many after the 2016 elections, the number of concealed handgun permits has again increased.

In 2018, the number of concealed handgun permits soared to over 17.25 million – a 273% increase since 2007. 7.14% of American adults have permits. Unlike surveys that may be affected by people’s unwillingness to answer some personal questions, concealed handgun permit data is the only really “hard data” that we have on gun ownership across the United States.

Still, an even larger number of people carry because in 14 states people don’t need a permit to carry in all or virtually all those states.

Among the findings of our report:

- Last year, despite the common perception that growth in the number of permit holders would stop after the 2016 election, the number of permits grew by about 890,000.

- Outside the restrictive states of California and New York, about 8.63% of the adult population has a permit.

- In fifteen states, more than 10% of adults have permits, up from just eleven last year.

- Alabama has the highest rate — 22.1%. Indiana is second with 17.9%, and South Dakota is a close third with 17.2%.

- Four states now have over 1 million permit holders: Florida, Georgia, Pennsylvania, and Texas.

- Another 14 states have adopted constitutional carry in all or almost all of their state, meaning that a permit is no longer required. However, because of these constitutional carry states, the nationwide growth in permits does not paint a full picture of the overall increase in concealed carry.

- Permits continued to grow much faster for women and minorities. Between 2012 and 2018, the percent of women with permits grew 111% faster for women and the percent of blacks with permits grew 20% faster than for whites. Permits for Asians grew 29% faster than for whites.

- Concealed handgun permit holders are extremely law-abiding. In Florida and Texas, permit holders are convicted of misdemeanors and felonies at one-sixth of the rate at which police officers are convicted.

The report is available to be downloaded here.

One really weird looking pistol is all that I can say about it!

|

The Steyr-Mannlicher Model 1900 Autoloading Pistol by Ed Buffaloe Ferdinand von Mannlicher (1848-1904) studied engineering at the Vienna Technical College and in 1869 began working for the Austro-Hungarian railroad industry. During his tenure with the Kaiser-Ferdinand-

When he returned to Europe Mannlicher began to design a repeating carbine, and in 1885 invented the clip loading mechanism that was used for many repeating rifles and early automatic pistols. He retired from railroad work in 1887 and began to devote himself full time to designing repeating mechanisms for rifles and pistols. He became such a prolific small arms designer that he has been referred to as Austria’s John Browning. He was granted as many as 150 patents during his lifetime, and his designs have had a pervasive influence right up to the present day.Mannlicher designed several pistols prior to the 1900. His Model 1894 (Austrian patent number 44-2911 of 3 July 1894) was an unusual double- action blow-forward design, wherein the barrel moved forward as the bullet sped through the bore. The barrel would lock in the forward position until the the trigger was released, whereupon it would return and another cartridge would be chambered.

Only about 300 of the original M-1900 in 8mm were manufactured. About 12,000 total of the Models 1901-1905 were made. The gun was never adopted by the Austrian military, though it was often purchased privately, and the 1905 version, shown here, was adopted by the Argentine military. Due to its popularity in South America, a few near copies were made in Spain. There were several minor changes made during the brief lifetime of the gun, and variations are often found, particularly in barrel length. Serial numbers began with 1 in 1901, and started over again each year of production (1901, 1902, 1903, 1905). Most of the M1905 guns available today are Argentine military surplus and had the Argentine crest ground off the right side plate before they were sold. A few, however, retain the crest and these guns are prized by collectors. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Copyright 2009-2013 by Ed Buffaloe. All rights reserved. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||