Author: Grumpy

The Gift of a Lifetime by VANDERLEUN

What would I do with my last box of .22 Long Rifle? First, I’d ask that it be a 100-round, hard-plastic box of good high-velocity hollow-points, like 37-grain Super-X’s or CCI Mini-Mags. I won’t cheat and call a 550-round value pack “a box.” Then I’d put it away and write my 6-year-old son, Anse, a letter for him to read after he gets a little older:

Son, this is a curse. I had thousands of .22s to shoot up when I was your age, but you only get these. That’s a raw deal for someone with your interests and inclinations, but life’s full of raw deals. You’ll manage.

You can learn a lot with a .22 rifle and 100 rounds, so long as you don’t do something stupid with them, like shoot road signs or the old appliances laying in the creeks.

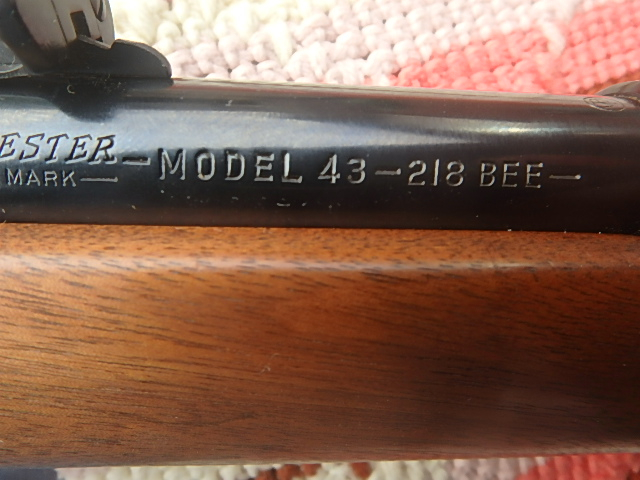

Get a rifle to call your own. If there’s an old one of mine you like, I’ll give it to you. But don’t be afraid to shop for yourself. Nostalgia doesn’t make a rifle shoot, and in fact, I’ve seen plenty of old guns that weren’t worth a shit. When you get a really good rifle, you’ll know it. Until then, know that searching for it is one of life’s great pleasures.

When you have it, save your money until you can buy a good scope, otherwise you’ll spend just as much on two or three cheap ones that you won’t like. Get good mounts, too. With just 100 rounds, you can’t be fretting about your gun being off.

Don’t leave anything to chance when you check your zero. Get a good rest on a solid bench, on a range with no distractions. Just about every problem I’ve ever had sighting in a gun happened because of a shaky table or contorted shooting position. You don’t have many shots, son, so be sure not to waste them here.

Then, you know what to do: Wait until the last week in August or the first one in September. Head to the hardwoods. Any of the ridges we’ve always hunted will be fine. Go alone. Pick a sunny morning that’s calm and still and cool—maybe 12 hours after a rain so the leaves on the ground are soft and quiet. Don’t go if it’s been raining all night, though, because the droplets will still be falling from the canopy, and it’s hard to tell the difference in that sound and the sounds of squirrels cutting.

Look for the mature pignut and shagbark hickories. There’ll be one or two growing for every 10 oaks on a ridge, and you know what they look like. If you hear a hickory nut fall to the ground, it’s probably because a squirrel dropped it, since the mast around here doesn’t fall on its own until late September. Stand there a minute or two, and listen for teeth scraping on the nut. Then you’ll know for sure.

Sneak up on the sound. Watch for limbs shaking. Use the shadows to get close. If you spook a squirrel it’s OK, because there’ll be another one—but eventually you’ll learn how to get right under them, and almost never spook them. Find a sapling for a rest, one that’s several inches around so the trunk doesn’t flex and so that you’re solid, and shoot the squirrels in the head. Take no other shots but that. Clean every squirrel, and cook them for yourself or share them. Don’t ever waste one.

One hundred rounds of .22 won’t last long, but it’s enough, if you use a few each fall, to learn how to do this. And if you learn how to do this, you can go hunting for anything else, anywhere on the planet, and hold your own just fine. —Will Brantley

Some words of Wisdom!

Choose Your Battles Wisely

After President Biden announced that the federal government was going to force as many people as it possibly could to get vaxed, the deplorable patriots and domestic insurrectionists of the Vast Right-Wing Conspiracy immediately took to the Internet to express their outrage. Many of them vowed (some of them quite explicitly) to rise up in armed rebellion against a tyrannical government, which is exactly what the Deep State has been salivating for so that it can initiate a maximum-force crackdown on anyone who opposes the actions of FedGov.

I have just three words to say to those good patriots who are ready to pledge their lives, their fortunes, and their sacred honor to overthrow the despotism that is being imposed on them:

YOU’RE BEING PLAYED.

It’s not the first time such a trap has been sprung on you. I can remember several recent similar operations, beginning with the occupation of the Malheur Wildlife Refuge back in 2016. It was pretty clear from the beginning that the patriots had been set up by the feds, and we were fortunate that the trial judge eventually required the prosecution to reveal who the FBI agents were among the occupiers. It turned out that a remarkably high percentage of the group (I forget exactly how many) were FBI informers, including one at a high level of the leadership with responsibility for strategy and planning. In other words, the foolhardy mission was at least partially instigated and directed by the FBI.

In that small battle against tyranny, the patriots lost. The operation was tailor-made to provide reams of negative publicity against them in the media, turning at least some portion of public opinion against those who stand up for their Second Amendment rights. LaVoy Finicum ended up dead, the patriots went on trial and just barely escaped long prison terms, the movement was discredited, and all for nothing.

They were played.

Except for the exposure of their infiltrators, the Feds won big-time on that one.

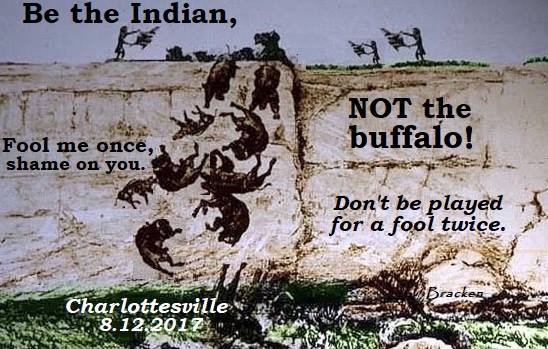

It was obvious from the get-go that Malheur was a set-up. It prompted Matt Bracken to create this meme pic in advance of the next one, the “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville in August of 2017:

Wiser heads could tell it was a set-up, and stayed away. But enough people took the bait and showed up to create another fiasco, providing the Deep State with exactly what it wanted. The organizer of the event was clearly a government plant. Rent-a-Nazis were bused in to provide the desired photo-ops for the media. And the patriots were kettled in what was then called Lee Park, to be ushered out into the waiting arms of Antifa on Market Street at the end of the event.

The Deep State and the media got their martyr, and significant political damage was done to Donald Trump, which was the main objective. Now the statues of General Lee are gone from everywhere, and Trump has been successfully deposed. It was a big win for the feds, much bigger than Malheur, and the patriots gained exactly nothing from it.

They were played.

The next big one was the “insurrection” at the Capitol on January 6, 2021. That was also an FBI-managed event, probably to an even greater extent than Malheur. Antifa operatives turned up in MAGA gear to create the desired photo ops making Trump supporters look violent and evil. A large number of earnest, well-meaning, but imprudent patriots were deliberately let into the building to make sure that there would be hundreds of “insurrectionists” — cannon fodder — arrested for the eventual show trials. And once again Trump supporters were discredited in the eyes of millions of their fellow citizens who might have sympathized with their cause under other circumstances.

The consequences of that ill-advised operation are still playing out. The omnipresent surveillance imposed by the Patriot Act is being extended even further. Those who publish material like this that criticizes the State — or even milder dissent — are being marked as domestic terrorists.

It was a massive loss for the patriots, who gained nothing from it.

You were played.

Please don’t be played again this time.

Ever since January 6 the DHS, and especially the FBI, have been busy assembling the next trap for all those good patriots who just can’t learn from their mistakes. Every obnoxious totalitarian action of the past eight months has been designed to provoke Second Amendment supporters into imprudent action.

First they made us angry by withdrawing from Afghanistan in the worst possible fashion, making sure to endow the Muslim Brotherhood with better armament than the mujahideen had ever dreamed of.

Then they told us that we must get vaxed, and that they could and would force us to do so if we didn’t comply.

For many people this was (rightly) the last straw. Angry patriots are now ready to take up arms against federal tyranny. Which is exactly what the Deep State wants.

Just think about what happens when you grab the AR-15 and assemble at a local park with fellow like-minded patriots.

First of all, this is what the feds expect. They’ve spent many months preparing for it. They have unlimited funds at their disposal, which you don’t. They do this stuff full-time, which you don’t. They’ve spent all day, every day putting together the exact operation they want, on a battlefield of their choice, and at a time they have chosen. They’re ready for you.

And, most important of all, you’ve been infiltrated. Wherever two or three are gathered, at least one is an FBI informer.

I operate solo, so unless the feds have infiltrated a lobe of my brain (which is always possible), I don’t have to deal with this sort of thing personally. But over the last fifteen years I’ve watched it happen to various groups I’ve been in contact with, on both sides of the Atlantic. They always get infiltrated. It’s inevitable.

So you’re under constant surveillance. The feds know what you’re doing, and if you engage in any group planning at all, they’re aware of it. The moment you take that weapon into your hands, they will spring the trap on you and your companions. This is what they want; they’re ready for it.

Be the Indian, NOT the buffalo!

As Jesus said (Matthew 10:16), “Listen carefully: I am sending you out like sheep among wolves; so be wise as serpents, and innocent as doves.”

This doesn’t mean that you should take no action against your oppressor. It simply means that such action should be chosen thoughtfully and carefully, after lengthy deliberation, always bearing in mind what I outlined above.

You will choose the nature of the operation. You will choose the time and the place, so that it will be when the enemy least expects it. And your initiative doesn’t necessarily have to involve armament — the war that is being fought against us is largely an information war, and we can be effective in our turn by using information against our adversaries. By and large we’re smarter than they are, so we can play their game better than they do.

Big Country Expat, a.k.a. the Intrepid Reporter, has some (warning: salty language) shrewd thoughts on the topic that may prove useful to you.

And The Smallest Minority warns against “Taking the Ticket to Ft. Sumter”. Because that’s what you’ll be doing if you up and grab your gun to go after the feds. That will give them the excuse for the massive crackdown they’ve been lusting after. They have far more power than we do, at least for the time being, and they will squash us like bugs.

To finish up, I need to return to the topic of infiltration.

If you’re part of a group, unless it’s made up entirely of close kin and/or good friends that you have known continuously since grade school, then you have been infiltrated. It’s inevitable. Even a modest-sized patriot group will have at least one FBI informer among its membership.

I’ve always counseled people to take the time and effort to mount counterintelligence operations within their group. It’s a dirty job, but somebody has to do it. You will need to vet everybody suspiciously, trusting no one except possibly your grandma — but even she warrants a background check.

When I was in Europe at a Counterjihad conference more than ten years ago, the guy who drove us around the city and acted as a tour guide later turned out to be a police agent. He was a really nice guy, and probably genuinely sympathetic to our cause, but nevertheless was still reporting everything back to his superiors.

And I wasn’t surprised, because I expect infiltration. I didn’t organize the conference, and I didn’t speak the local language, so running a counterintelligence operation wasn’t a possibility. But I knew there had to be informers; there always are.

When you discover infiltrators (which you eventually will, if you do your job right), kicking them out of your org is not necessarily the best response. A known informer can be useful if he or she is spoon-fed carefully targeted information, including disinformation, that will be passed back to superiors in Fed.gov.

In pre-revolutionary Russia the Czar’s secret police were known as the Okhrana, and they were very good at their job. They planted informers in all the socialist and anarchist groups so that they could learn what was being plotted, and act to thwart it.

Lenin was well aware that the Bolsheviks had been infiltrated, but he was a smart guy, and tasked trusted comrades to track down the informers. They weren’t summarily dispatched, however; instead they were turned, or used as unknowing conduits of disinformation back to the Okhrana.

Stalin was reportedly an Okhrana agent who was turned by the Bolsheviks. As a power-hungry psychopath, he probably fancied his prospects under the revolutionaries more than he did those under the ancien régime.

I’m not advising people to use Lenin and Stalin as role models. But you need to be at least as savvy as they were in dealing with infiltrators.

Make no mistake about it: you will be infiltrated. You have been infiltrated. It’s a given.

Why Were Vietnam War Vets Treated Poorly When They Returned?

American soldiers returning home from Vietnam often faced scorn as the war they had fought in became increasingly unpopular. None were looking for a parade but all were certainly looking for human support and help in readjusting back to civilian life after their brutal war. Why did it happen? Here’s one opinion and some possible answers.

It was after returning to the U.S. and while en route to the hospital that Wowwk first encountered hostility as a veteran.

Strapped to a gurney in a retrofitted bus, Wowwk and other wounded servicemen felt excitement at being back on American soil. But looking out the window and seeing civilians stop to watch the small convoy of hospital-bound vehicles, his excitement turned to confusion. “I remember feeling like, what could I do to acknowledge them, and I just gave the peace signal,” Wowwk says. “And instead of getting return peace fingers, I got the middle finger.”

The Vietnam War claimed the lives of more than 58,000 American service members and wounded more than 150,000. And for the men who served in Vietnam and survived unspeakable horrors, coming home offered its own kind of trauma. Some, like Wowwk, say they had invectives hurled their way; others, like naval officer Ford Cole, remember being spit on. As a cohort, Vietnam veterans were met with none of the fanfare and received none of the benefits bestowed upon World War II’s “greatest generation.”

No ‘Welcome Home’ parades for Vietnam vets.

This was partly due to the logistics of the never-ending conflict. The Vietnam War lasted from 1964-1973—the longest war in American history until it was overtaken by the one in Afghanistan—and servicemen typically did one-year tours of duty. Unlike conflicts with massive demobilizations, men came back from Vietnam by themselves rather than with their units or companies. For a decade, as one person was shipped off to fight, another was returning.

“The collective emotion of the country was divided,” says Jerry Lembke, a Vietnam veteran, sociologist and author of The Spitting Image: Myth, Memory, and the Legacy of Vietnam. “For the family whose son is just coming back, you aren’t going to have a public welcoming home ceremony when someone’s son just down the road was just sent off to Vietnam.”

As the war ground on and became increasingly hopeless, the military personnel put through this kind of revolving door of service came to represent something many Americans would rather not accept: defeat. “Vietnam was a lost war, and it was the first major lost war abroad in American history,” Lembcke says. “You don’t have parades for soldiers coming home from a war they lost.”

GI benefits were lacking.

Celebrations aside, the government also failed to make good on its promises to those who served. Veterans returning from Vietnam were met with an institutional response marked by indifference. Peter Langenus, today the Commander of VFW Post 653 in New Canaan, Connecticut, commanded Delta Company, 3rd Battalion/7th Infantry, 199th Light Infantry Brigade from 1969-70. He led his men on operations that lasted 30 days or more in some of Vietnam’s most inhospitable conditions, “without shaving, bathing or changing clothing. None of that,” he says, “prepared me for the reception at home upon our return.”

Back in the States, Langenus quickly discovered the GI benefits available for Vietnam veterans “were almost nonexistent.” While living in New York, he developed symptoms of malaria—a tropical disease fairly uncommon in the concrete jungle—yet he was denied VA health care because he didn’t display those symptoms in Vietnam. He graduated from Notre Dame prior to being commissioned, and after his service returned to law school to cash in his educational benefits. “At a time when I was paying $300 a credit, my entire educational benefit was $126.” And when it came to finding a job, he was met with thinly veiled disgust and discrimination from law firms upon learning he was a Vietnam infantry veteran.

“The society really was ill-prepared to give these guys what they deserved,” says Christian Appy, professor of History at the University of Massachusetts Amherst and author of three books on Vietnam. “They were not necessarily looking for a parade, but they were certainly looking for basic human support and help in readjusting to civilian life after this really brutal war.”

Part of the reason was economic. While the economy after World War II was one of the most robust in American history, during and after Vietnam the nation was in a death spiral of stagflation and economic malaise. And as more and more wartime atrocities came to light, there was a national implication of guilt and shame placed on Vietnam veterans as participants in and avatars of a brutal, unsuccessful war. In popular culture, the stereotype of the broken, homeless Vietnam vet began to take hold thanks to films like The Deer Hunter(1978), Coming Home (1978) and First Blood (1982).

The Gulf War saw a shift in attitudes.

It would take nearly 20 years after the end of the war for America to get right with its Vietnam veterans. The dedication of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in 1982 began the process, but many identify the Gulf War of 1990-91—with its national flag-waving, yellow-ribbon cultural mobilization and the grand celebrations of a successful campaign—as ending Vietnam Syndrome. “The Vietnam veterans, we couldn’t believe it. We could not understand getting letters from school kids,” says Langenus, also a veteran of Desert Storm. “You couldn’t believe that people were cheering you.”

Since 9/11, patriotic gestures, like wearing flag pins and saying, “Thank you for your service,” have become common, as more troops are sent to Iraq and Afghanistan. But the specter of Vietnam still lingers, and some of that war’s veterans view such acts with a wary glance.

“Deeds need to be done in addition to words,” says Wowwk, who is 100 percent disabled from his Vietnam wounds. “I appreciate the respect of ‘thank you’ because that was something I never received when I came home. It’s better than nothing. It’s better than them walking away and not even recognizing you. But what are you doing in addition to saying ‘thank you’?”