Ahh, the Urban Legend! The centerpiece of countless gun store discussions, campfire stories, bar tales and heated arguments. As a soft-brained purveyor of gun information, I’ve run across my fair share of firearms-related myths and urban legends.

My own relationship with the phenomenon is quite unhappy. While I enjoy a good apocryphal tale as much as the next fellow, I quickly learned as a gun and outdoor writer that publishing information or opinions contradicting well-accepted folklore is tantamount to telling someone their baby is ugly or their wife is fat. It doesn’t go well.

I first learned this lesson decades ago while writing a weekly outdoor column in the local newspaper. As a scuba-diver, I commented on an old chestnut I’ve now heard in nearly every state and a couple of foreign countries: below a large local dam, there is a catfish so huge a diver sent down to do repairs swam into its mouth and after barely escaping, refused to go into the water ever again.

Most rational people realize a catfish with a five-or-six-foot wide mouth — large enough for a fully equipped diver to swim into — would probably be somewhere in the neighborhood of 30 or more feet long. Think “whale.” Such a critter would be hard to hide even in a major river system.

Stick with me here: it didn’t happen. Yes, there are some large catfish out there, some even weighing upwards of 125 pounds and a mouth pushing 12” in diameter, but this story is just that — a story. However, a small subset of people rigorously believe it, and I’ve got the hate mail to prove it.

Same thing with the legend of various Fish and Wildlife Departments secretly releasing poisonous snakes wholesale into the countryside, along with my favorite — the parachuting badgers into the wilds as some kind of nefarious plot to harm the ecosystem.

Why wildlife managers would secretly want to ruin the very thing they are sworn to protect doesn’t seem to occur to the folks who accept this at face value.

Once, when I disputed this story in print, I actually got a half-hearted death threat. The letter writer “knew for a fact” the program was underway because his step-uncle’s cousin’s barber’s niece once met a guy in a bar who knew somebody who helped load airplanes with the chute-equipped badgers.

While writing my follow-on response, I actually called my state Division of Natural Resources and asked if they had secretly been dropping these short-tempered members of the weasel family into the countryside. The lady on the phone asked if I had been drinking.

I also inquired where the agency purchased the wholesale case-lots of badgers needed and how they picked the unfortunate soul who was assigned to fit the biting and clawing beasts into their harnesses. It just didn’t make sense. It’s a good story, yes, but not legitimate — just like most shooting urban legends.

Shooting myths and urban legends have been around since gunpowder!

Gun Stories

The gun world is rife with such misinformation, and woe to the gun writer who punctures these cherished “realities.”

I had a good example thrust into my lap, even though it was totally unrelated to journalism. I was assigned to sit on a panel reviewing the final presentations of police officers seeking to become certified instructors.

An earnest young instructor candidate strode to the podium and began his presentation on exterior ballistics. Things were going fine until he endeavored to explain how bullets continue speeding up after leaving the muzzle before they begin to slow down.

I was dumbfounded. The central point of his presentation was wrapped around this dubious “fact.” He had somehow conflated the normal parabolic arc of bullets relative to the sights with an increase in speed.

When I tried to gently point out his error, he proceeded to become more and more agitated while using ever-more fantastical — and non-existent — physics to explain the concept.

He was so absolutely sure of the matter someone in his past had likewise explained the concept to him and he could not begin to fathom it might be incorrect. But he was certainly wrong, absolutely, positively 100% wrong.

As an aside, in case you are within the tiny fraction of shooters who still believe in this urban legend, bullets (or any object) can only increase velocity when additional kinetic energy is applied, otherwise it will continually slow down due to friction. Once a bullet leaves the muzzle, no additional energy is added (unless the bullet contains a tiny motor), so it starts slowing down immediately while thrashing its way through air molecules.

The bullet does indeed move in an arc relative to the sightline, but this is intentional because of how the bore line and sights are positioned, not because the bullet is speeding up. If the sighting system were exactly parallel to the bore, the bullet would never strike the point of aim because it continually drops. I might not have explained it perfectly, and there are other minor forces at work, but this is a proven fact. If you are still shaking your head in disbelief, look it up from a reputable physics source.

Anyway, shooting is replete with such urban legends of every variety. If you think magazine springs take a ‘set’ after a few years, they don’t. There is no “ultimate manstopper,” and “Knockdown power” doesn’t really exist.

Bullets don’t knock people backward — they might stumble or even launch themselves through the plate glass window if they think that’s what’s supposed to happen when shot, but the kinetic energy of the bullet cannot do it. This is why big guns can be effectively shot by diminutive people. If not, they’d likewise be flung backward out the saloon door upon firing. It’s the old “Equal-but-opposite forces” law of physics.

Meanwhile, cartridges did not “hit harder” or travel faster in the ‘old days’ given the same material and loadings. Manufacturers are not intentionally suppressing a new gun or cartridge because it was too good in testing. The truth is far more mundane — they simply project possible sales versus cost and decide if the product is economically feasible to manufacture.

There is no magic cartridge or bullet design which works every time. The truth is, bullet placement is far, far more important than the flavor — or cost — of the projectile.

The sound of a pump-action shotgun being racked doesn’t always stop a fight. Shooting someone outside your home and then dragging them inside isn’t going to protect you from prosecution and will likely have the opposite effect. Bulletproof vests don’t always live up to their name. Meanwhile, silencers mostly are not.

It’s also an urban legend all gunfights are “Three yards, three seconds, three shots.” Many are, but there are a sizable number which aren’t. This is why you should be able to hit at all reasonable ranges for your particular weapon.

And the “Gun Show Loophole” doesn’t exist. Of course, if you want to get into the Gun Control urban legends (let alone the lies), we’ll need a few hundred more pages.

Any discussion of firearms folklore certainly must mention the Old West. The history of the western U.S. is rife with shooting mythology, but the biggest of all is the “Gunslinger” trope — two steely-eyed men standing mano-a-mano in the street at high noon. Sorry, but it is literally a legend. Only two or three such actual duals have ever been discovered by historians. Sorry, Hollywood!

The Big One

And finally, there is the biggest firearms urban legend of all — “Gun writers are just shills for manufacturers!”

Sorry to bust your bubble on the last one, kids. Writers — and editors and magazines/websites — do have a vested interest in keeping gun makers on their good side, but there are very few (rumored) instances where a lousy gun or load was intentionally given glowing press simply to keep the hogs at the trough.

Trying to keep a positive relationship with an industry partner is simply good business sense, but writers walk the fine line between maintaining a relationship so they can have future access to information and products and sharing every blemish.

I’ll never claim we give a total, comprehensively unvarnished report on every topic, but we do try to bring the reader everything they need to know in an entertaining way. So far, it’s worked for almost 70 years.

And you can count on this as a fact, not an urban legend!

Deadliest Rifle Cartridge of WW2

I beg to differ on this one as the A Bomb was in a league of its own. Grumpy

Oops!

The 45-70 Govt. carries a powerful mystique. Big bore. Heavy hitter. Knockdown power. A favorite of commercial bison hunters in the 1870s. So how do you think it performed on this 90-pound African warthog?

Fort Richmond Safaris PH Geoffrey Wayland said “shoot that warthog” when this old boar appeared in the short grass. My beautiful, borrowed Marlin Model 1895 from the Custom Shop (Skinner peep sight, case colored receiver, large loop lever, 18.5″ octagonal barrel, Wild West trigger, hand-checkered extra-fancy walnut) rose to the occasion and sent a 300-grain Barnes TSX bullet 108 yards to land on the leading edge of the boar’s shoulder. What happened next is the heart of this story.

45-70 Govt. Up Close And Personal

Here are the clinical details: The 300-grain Barnes bullet left the muzzle at roughly 1,800 fps carrying 2,159 f-p of energy. At its impact range of 108 yards, remaining energy should have been about 1,500 foot-pounds. That is theoretically enough power to lift 1,500 pounds a foot above the ground or a 100-pound warthog 15 feet straight up. This particular old pig hadn’t read the ballistic tables. Instead of flipping through the air, recoiling several feet backward, or even falling on its side, the old boar merely ran as if alarmed.

“Did I miss?” I asked Geoffrey.

“No, you hit it. Let’s go see.”

While tracker Pa searched for a blood trail (there was none,) Geoffrey and I moved ahead along the hog’s line of departure. After about 150 yards we spotted our quarry lying on its side. But it wasn’t quite dead, so I applied one more 300-grain slug between the forelegs, up through the heart and lungs and out the back. That shot did not move the small desert hog so much as an inch.

Whether the 45-70 Govt. can knock down a warthog or not, hunting with that historic cartridge in a Marlin lever-action as beautiful and smooth as this one adds challenge, depth, and romance to any hunt. Shot placement beats “knockdown” power every time.

Post Hunt Autopsy Of 45-70 Govt. Performance

Our post-hunt autopsy revealed the first bullet had struck just in front of the boar’s right “shoulder,” mid-height, passed above the heart and through the lungs the length of the thoracic cavity. It then punched through the diaphragm, into the paunch, and exited in front of the left ham. No structural bones were hit, but the bullet traversed most of the vital organs we hunters aim to disrupt.

So, let the conjecture and arguments begin. But don’t make the common mistake of condemning the 45-70 Govt. cartridge, the 300-grain Barnes TSX bullet, the Marlin rifle, or the shooter on this one incident. Both Geoffrey and I called the hit nigh perfect. The bullet obviously had sufficient momentum for complete penetration. The .458″ bullet had the diameter many big bore advocates insist is necessary for creation of an adequate wound channel (this ain’t no puny 6.5mm anything!) And you can’t convince me the Barnes TSX with its wide, hollow nose cavity failed to open. Yes, there is the chance that this particular pig was tougher than most and persevered despite perfect shot placement. Regardless, where was that famous bison-slaying knockdown power? That is the big question. If “knockdown power” were all it’s cracked up to be, why wasn’t this hog knocked down?

50 Years Experience Illustrates 45-70 Govt. Performance

Fifty years of hunting experience with a wide variety of cartridges and bullets on well over 120 different big game species have informed me that bullet placement and performance (expansion and penetration) trump so-called knockdown power every time. Hit the central nervous system and yes, you do knock down your prey. But it takes amazingly little power to do it.

Does this mean that a low energy cartridge with a light, small diameter bullet is just as effective as a 45-70 Govt? Not necessarily, but maybe. Sometimes. My advice — and this is echoed by Geoffrey, Leon, Mark and other PHs at Fort Richmond Safaris — is to hunt with and enjoy whatever cartridge you shoot well. Just don’t expect it to knock anything down. Strive for precision placement with a bullet designed to expand reliably at your anticipated impact energies and penetrate far enough to reach the vitals. And hone your tracking skills.

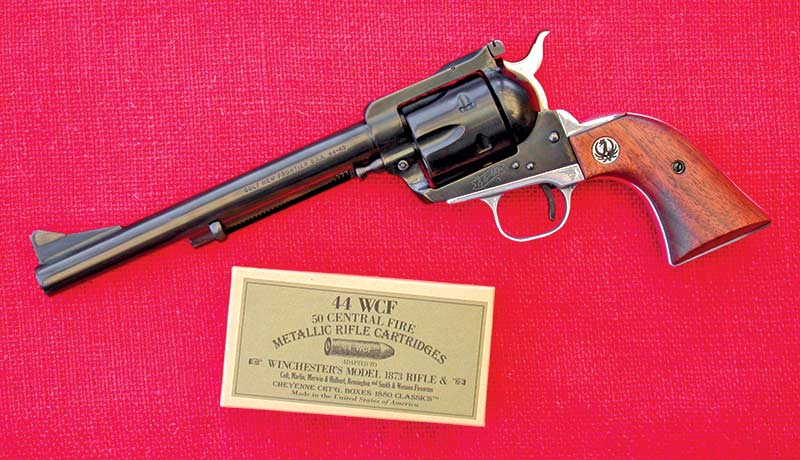

Currently produced 3rd Generation 7½” Colt .38-40.

Currently produced 3rd Generation 7½” Colt .38-40.

The Winchester Centerfire (WCF) sixgun cartridges actually started in the Winchester Model 1873 levergun. Even though they were originally rifle cartridges, they fitted nicely into the Colt SAA. It made a lot of sense to have a levergun and sixgun chambered in the same cartridge in the last quarter of the 19th century. Actually, it still does, which is why leverguns in .357 Magnum and .44 Magnum, especially, are so popular.

Five years after Winchester brought forth the .44 WCF, mostly known these days as the .44-40, in the Model ’73 levergun, Colt chambered their popular Single Action Army in the same cartridge. Meanwhile, Winchester necked down the .44-40 to .40 caliber and called it the .38 Winchester Centerfire.

In 1884, Colt began offering the Single Action Army in the new .38 WCF. The .44-40 is basically a .45 necked down to .43. A bottleneck cartridge feeds much more smoothly through the action of a levergun.

The most popular chambering in the Colt Single Action Army in the 1st Generation run from 1873-1940 was the .45 Colt, followed by the .44-40, and then the .38-40 came in third with about 30 other chamberings filling out the balance. With all the excellent straight-walled sixgun cartridges we have, such as the .44 Special, .45 Colt, .44 Magnum, and .41 Magnum, I cannot come up with a single practical reason for the existence in the 21st century of the .44-40 and/or .38-40.

But does shooting always have to be practical? Sometimes, we do things just because they’re fun and/or connect with past history. The .44 and .38 WCFs do both.

We now have access to high-quality leverguns, which are replicas of the Winchester 1873 and Winchester 1892, and they add to the fun of shooting and the connection with the past when chambered in .44-40 or .38-40 as a companion carbine to the Colt Single Action.

I’ve hunted a lot with a .44-40 sixgun and have yet to have any deer-sized game or jackrabbit complain because it wasn’t a .44 Special or .44 Magnum, and the .38-40 will always have a special place in my sixgunnin’ heart as my first centerfire sixgun more than 55 years ago was a 4¾” Colt SAA .38 WCF circa 1900.

130+ years of 7½” Colt .44-40s: 1880s Frontier Sixshooter, 1873 Peacemaker Centennial Frontier Sixshooter, and 3rd Generation .44-40.

Reloading Bottlenecks

There’ve always been those who complain about the difficulty of loading these cartridges. Other than the extra step of having to lube the brass (which I do anyway with straight-walled cases simply to make the sizing operation easier), both the .44-40 and .38-40 are no harder to reload than the other sixgun cartridges.

I place about 100 empty cases in a cardboard tray, spray with lube and they are ready to run on the RCBS Pro-2000 progressive press. In the past, there was often a problem as both cartridge cases were very thin and fragile at the neck. In recent years, I have switched exclusively to Starline, and I have rarely ever lost a case.

Brian Cosby crafted this custom .44-40 using a Ruger

Old Model and a 7½” Colt New Frontier barrel.

Generations of Art

The Colt Single Action Army was so superbly designed it still exists nearly 140 years after its introduction with more than one-half million being produced. Everything about the original Colt Single Action Army is perfection.

The grip frame, borrowed from the 1851 Navy, is the most user-friendly grip ever designed for shooting standard loads; the hammer is just the right angle for most thumbs to reach; the balance is so good it has never been surpassed; and it is the most naturally pointing sixgun ever designed.

The sixguns produced by Colt from 1873 to 1941 are normally found to be superb examples of the gunmaker’s art. The early 2nd Generation Colts were also fine sixguns.

The 2nd Generation run ended in the early 1970s but was resurrected as the 3rd Generation in the mid-1970s. Single Actions coming from Colt today are as fine as anything they have never produced. Colt did not add the .44-40 to their production schedule with the introduction of the Second Generation sixguns.

The only Second Generation .44-40 found is the nickel-plated 7½” Frontier Six Shooter found in the Peacemaker Centennial run of commemoratives, with 2,000 being made. This is probably one of the finest .44-40 Colt Single Actions ever produced. Colt made no .38-40s during the 2nd Generation.

Custom WCFs on Old Model Ruger .357s from top: 7½” .38-40 by Larry Crow, 4¾” .44-40/.44 Special Convertible by David Clements, and 7½” .44-40 by Brian Cosby. The .44s have Colt New Frontier barrels.

Flat-Top Target

In 1962, Colt introduced their modernized version of the Flat-Top Target, with the New Frontier having a Flat-Top frame and adjustable sights. When the Single Action was resurrected as the 3rd Generation, Colt also brought back the New Frontier, including a 4¾” .44-40. I think so much of mine it has now been fitted with one-piece ivories.

The .38-40 has also been produced in the Third Generation run of Single Actions. Mine is one of the very early ones with a 4¾” barrel, and it has been fully engraved by Dale Miller along with a companion .44-40 in the same barrel length. My more recent WCFs are from the current production, a 4¾” .44-40 and a 7½” .38-40 and they are excellent Single Actions in every way.

These Colt .44-40 Frontier Sixshooters are from

1897 and 1903; the leather is by Will Ghormley.

New Service

Ask shooters to name Colt’s most popular large frame sixgun prior to World War II, and most will come back with the answer of the Single Action Army, with more than 357,000 having been produced from 1873 to 1941.

However, when it comes to the number of units produced, the Single Action Army comes in a very close second to a Colt whose production life actually lasted 25 years less than the beloved Peacemaker. By the end of the 19th century, both S&W and Colt had introduced their versions of the double-action sixguns that would dominate much of the 20th century.

From S&W came the first Military & Police in 1899; however, it had been superseded one year earlier by Colt’s New Service. S&W’s modern revolver was built on a .38 platform that would become the K-Frame. Colt went much larger, even larger than the S&W N-Frame .44 Special, which would surface 10 years later. In their 1940 catalog, Colt offered three versions of the big New Service with barrel lengths of 4½”, 5½”, and 7½” and either blue or nickel finish in both .44-40 and .38-40. Both of my WCF New Service sixguns are blue with the .44-40 having a 7½” barrel and the .38-40 wears the shorter 4½” length. Both are excellent shooters.

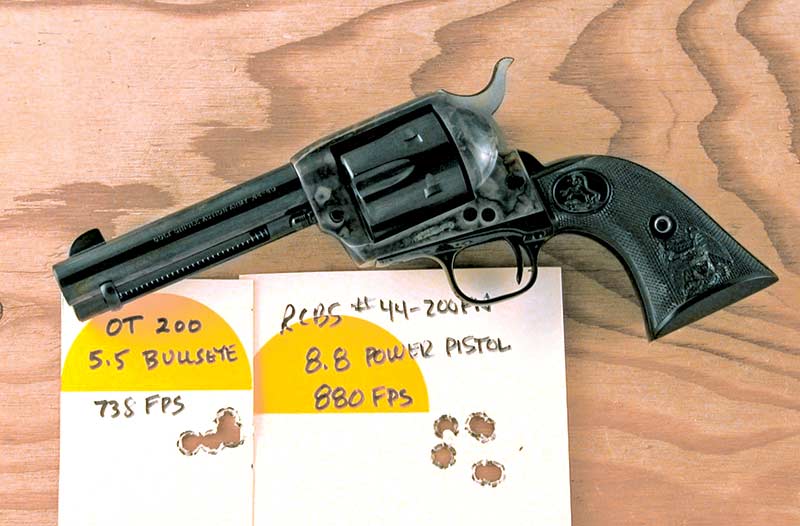

Targets shot with a current production 4¾” Colt .44-40.

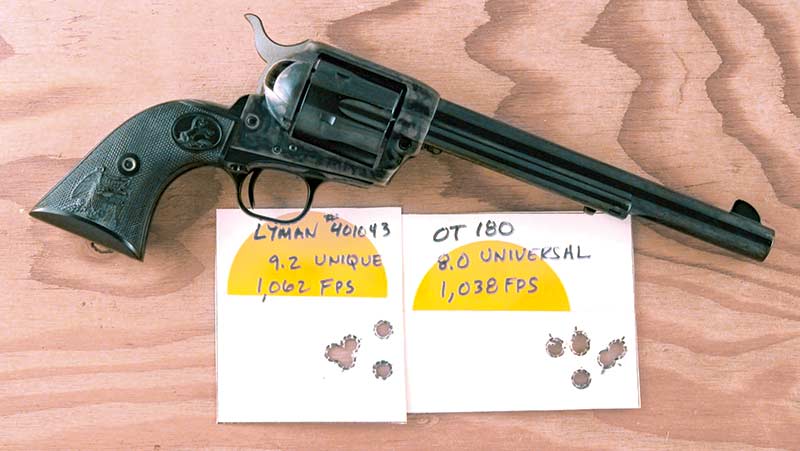

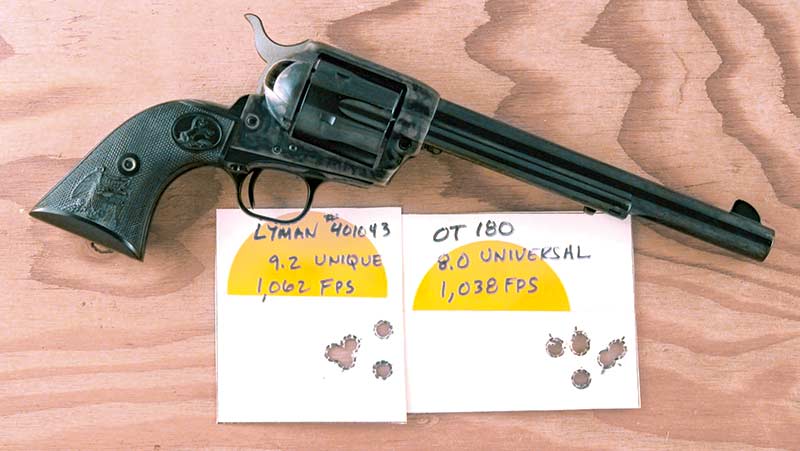

Targets shot with a current production 7½” Colt .38-40.

Holdover cartridges from the 1870s-1880s compared:

.44 Russian, .45 Colt, .44-40, and .38-40.

Dual Cylinders

When there was a real shortage of .44 Specials, especially in the 1970s, many sixgunners started with a Colt Single Action .44-40 and added a second cylinder in .44 Special as both barrels have the same dimensions. It is just as easy to go the other way — start with a .44 Special and add a .44-40 cylinder. I have done this with Colt Single Actions, a New Frontier, and even a Texas Longhorn Arms West Texas Flat-Top Target.

And what we do with a Colt Single Action can be done just as well with a Ruger. Not just any Ruger will do for converting to .38-40, or .44-40, or a dual-cylindered project. New Model .357 Rugers are too big and bulky, and that is why the most popular sixguns for conversion are the Three Screw .357 Blackhawks, the Flat-Top made from 1955 to 1962 and the Old Model from 1963-1972. A Ruger New Model .357 converted to .44-40 or .38-40 will be the same size as a .44 Magnum Blackhawk without the versatility.

There are New Models that are exceptions, namely the 50th Anniversary .357 Blackhawk, .44 Special Flat-Top Blackhawk, and the New Vaquero. All of these have the New Model transfer bar safety and yet are the same size as the original Three Screw .357s.

Barrels for single-action conversions on Rugers can be found in several ways. Custom barrels or Ruger .44 Magnum barrels from any model Ruger .44 Magnum can be utilized, or any Third Generation Colt Single Action or New Frontier barrel has the same thread size, 24 tpi, as the Ruger main frames. New Frontier barrels look particularly good on Flat-Top or Old Model Rugers.

When my local gun shop, Shapels, was going out of business, I bought all of their .44 New Frontier barrels. One 4¾” .44-40 marked barrel was used by David Clements on a Three-Screw Old Model to build a Convertible .44-40/.44 Special sixgun. Expertly tuned and beautifully blued, this dual cylinder .44 has an action that is practically indestructible and shoots superbly with either cylinder.

A second New Frontier barrel, this one a 7½” version, was used by Brian Cosby to build a .44-40 on a Ruger Three-Screw, and Larry Crow built up what is one of my favorite .38-40s by re-chambering the cylinder and fitting a custom 7½” barrel on another .357 Ruger Three-Screw.

This gun is exceptionally attractive with its deep blue finish and gold accoutrements and is also an excellent shooter. I’ve done a lot of experimenting with different powders and bullets in both the .38-40 and .44-40 sixguns.

However, when I load a large batch of several hundred rounds, I normally go with 8.0 to 9.0 grains of Unique or Universal and 180 and 200-grain cast bullets, respectively. This gives me 1,000 to 1,150 fps in the .38-40 and 825 to 1,000 fps in the .44-40, depending on the particular sixgun and barrel length in both cases.