Since starting wwiiafterwwii, I receive from time to time suggestions for topics. These are wide-ranging but two in particular seem very popular: WWII weapons in the Vietnam War, which has been touched on several times; and a general question of how the world “cleaned up” WWII battlefields after the war. For the latter, I was surprised at how very little is written about it so perhaps this will be of interest.

One of the reasons WWII battlefields did not remain littered with vehicles for long was that, with the lone exception of the USA, all of the major warring powers made some official level of combat usage of captured enemy arms during WWII. The most formal was Germany’s Beutewaffe (literally, ‘booty’ or ‘loot’ weapon) effort, which encompassed everything from handguns to fighter aircraft with an official code in the Waffenamt system; for example FK-288(r) (the Soviet ZiS-3 anti-tank gun), SIGew-251(a) (the American M1 Garand rifle), and Sd.Kfz 735(i) (the Italian Fiat M13/40 tank). Captured gear was assembled at points called Sammelstelle and then shipped back from the front lines for disposition.

A notable figure during WWII regarding captured weapons was Major Alfred Becker, commander of the 200th Assault Gun Battalion of the 21st Panzer Division. After the 1940 fall of France, Becker was alarmed at the fate of Allied weapons. The Wehrmacht was at the height of it’s hubris, and quality captured gear was being taken as personal or unit trophies, junked, pushed into rivers to clear roads, etc. On his own time, Becker established a central office for cataloging, collecting, and modifying Allied weapons. This was located at the former Hotchkiss factory near Paris. After Erwin Rommel met Becker and was impressed, this ad hoc effort gained official sanction as Baukommando Paris (Paris Building Command). Becker designed no fewer than 25 different adaptations of Allied vehicles, including French hulls with Czechoslovak guns, Dutch trucks towing French guns, British hulls with German guns, and so on.

One of Becker’s creations (above) was a Czechoslovak Škoda A6 anti-tank gun inside a German enclosure set on a French Renault R35 tank hull.

After Germany invaded the USSR, use of captured Soviet weapons became widespread; so much that photos of German infantry with a PPSh-41 or PPS-43 are barely worth mentioning.

More common than capturing enemy weapons off a battlefield, was each side salvaging their own equipment. All of the major armies had repair & recovery units specializing in getting salvageable equipment off the battlefield. The Soviet and American armies were very adept at this, in both cases not only were there specialized recovery units but some themselves were sub-specialized in taking equipment off “hot” battlefields, even stripping or towing vehicles under the cover of darkness.

Meanwhile in nationalist China, civilian scavenger corps were allowed to follow units; in exchange for turning over militarily valuable things like guns or truck parts, they could keep whatever else they found. Above, a Chinese serviceman holds salvaged Arisaka Type 38 rifles and a Nambu Type 11 machine gun. After the end of WWII and then the end of the Chinese civil war, the PRC was still using ex-Japanese weaponry into the 1950s.

Above a pair of US Army M1 wrecker trucks right the tipped-over wreckage of a Panzer IV during a battlefield clean-up. The M1’s boom crane had a 10-capacity; so even with two working together leverage was needed to lift the 25-ton tank. Once the destroyed German tank was right-side up, it could be towed or dragged away by other vehicles.

The M32 is a good example of a WWII vehicle dedicated to recovering and towing wrecked tanks. Based on the M4 Sherman tank chassis, it had a 30-ton deadlift A-frame crane and a front-mounted winch. The highly successful M32 served in WWII, the Korean War, and beyond.

The Sherman ARV Mk.I was the British equivalent of the M32. This one is towing a recovered Panzer IV off a battlefield.

The vehicle which the M32 replaced was the M31, itself based on the M3 Lee tank. It had a 30-ton foldable boom. This photo shows the dummy gun to give it the look of an actual M3 Lee from a distance. Despite being officially “replaced” in 1944, M31s served until the end of WWII.

The M26 tank transporter was ideal for moving heavy loads cleaned up from battlefields. Above, a M26 moves a destroyed M4 Sherman in Italy during the latter part of WWII.

This M26 is moving a recovered Jagdtiger inside occupied Germany at the end of WWII.

As the Allies advanced upward and east from Normandy in 1944, a basic pattern for cleaning up battlefields was established. Tanks, other vehicles, and artillery were first moved to primary assembly points which were demined and clear of UXO (unexploded ordnance), usually railroad sidings, paved highway junctions, etc. From there, material was split up according to type, weight, damage level, etc and sent to “strip-out yards”.

A trio of Hetzers sits pushed out of the roadway shortly after Germany’s May 1945 surrender. Judging by the cyrillic road sign, this was in the Soviet occupation zone. These vehicles would later be moved to a primary assembly point and then to a “strip-out yard”.

Above is a primary assembly point in northwestern France in late 1944, with a variety of Allied and German vehicles awaiting transport to a “strip-out yard”.

Above is a “strip-out yard” near Caen, France near the end of WWII with a lineup of M4 Sherman tanks. Here, consumables and intact subassemblies were removed and sent to the supply pool for issue to operational M4s. What remained was then extracted and tossed into a general scrap pile. Finally the hulls themselves were either cut up if appropriate gear was available, or loaded onto flatbed rail cars for another, final round of processing somewhere else.

On the other side of the same Caen yard, German POWs pile up unusable pieces of steel to be shipped bulk as general scrap.

This pile of vehicle carcasses at Vilvorde, Belgium was a common sight in the Low Countries and occupied Germany after WWII. In some cases, entire piles of unwanted war salvage was bought as one lot by a local speculator, who would hold it until scrap metal prices rose.

Another reason to quickly clean battlefields was intelligence gathering. This King Tiger of the Waffen-SS 501st Heavy Panzer Battalion was recovered intact off a battlefield. The turret markings indicate it has been earmarked for evacuation by the US Army Bureau Of Ordnance.

After Japan’s surrender, many of the imperial army’s remaining tanks were in the home islands where they had been preparing for the expected invasion. Like aircraft described further below, General MacArthur’s policy was for immediate destruction, which was usually accomplished by dynamiting the tank, both destroying it and any ammunition and fuel inside. Local Japanese scrappers were allowed to then collect and sell the wreckage. Above is a mass tank dynamiting done by the US Army in occupied Japan in late 1945. On the left is a row of Type 97 Chi-Ha medium tanks, and to the right, Type 97-Kai Shin Ho-To medium tanks; an offshoot of the Chi-Ha. These Type 97-Kais are all missing their main guns, which may have been extracted by the Japanese for static bunker use towards the end of WWII.

A Type 94 tankette in occupied Japan being lined up for dynamiting in late 1945. A pre-WWII design, these little vehicles could be penetrated by .50BMG rounds from the M2 Browning machine gun at 600 yards.

Above, German soldiers surrender on one of the Greek islands in May 1945. The garrisons on Crete and several minor Aegean islands were marooned from the general German retreat during 1944 / 1945. The pile of 98k rifles and M38 gasmaskenbüchse (gas mask cans) was tasked to the UK for final disposition, but the overstretched British military in 1945 did not fully accomplish this, and a lot of ex-German weaponry fought again in the Greek civil war.

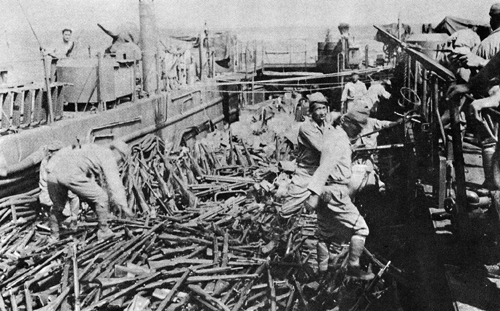

The US Army had no such problems with it’s occupation of Japan. Above, demobilized soldiers of the Japanese 58th Army throw Arisakas off a US Navy landing craft into the Pacific Ocean near Saishuto island. Hundreds of thousands of firearms were disposed of in this way, along with millions of rounds of ammunition.

Above, a destroyed Soviet IS heavy tank in Latvia during the summer of 1946, a year after the fighting in the Courland Pocket ended. This encircled German pocket, far cut off from the rest of the Reich, fought until the end of the war. Soviet cleanup of the three Baltic SSRs was hampered by an anti-communist insurgency that continued off and on for the remainder of the decade.

A former GI and his wife on honeymoon in France in 1947, pose on a StuG III with stahlhelm and wrecked MG-42. Two years after the end of WWII, there were still unrecovered tanks in France. The country was a popular honeymoon destination for demobilized servicemen between 1945-1949 as the US dollar was strong against the French franc. There was still danger to going off the highway in some rural areas, as not all land mines had been cleared and wrecks like this were often full of UXO (note the spent casings on the ground).

A staging area for surplus / salvaged weapons at Antwerp, Belgium in late 1945, several months after the end of WWII in Europe. In the foreground are British 17-Pounder field guns, behind them various American vehicles and German artillery. This equipment was collected for shipment across the English Channel for further disposition in Great Britain.

Also in Antwerp in late 1945 / early 1946, an embarkment pier for general war scrap, in this case vehicle parts and metal ammunition boxes. This was collected in Europe and shipped to England for recycling.

Taken several months after the German surrender, this photo shows a collection of Rakatenwerfer 43s in Pomerania. The late-war Rakatenwerfer 43 was not a gun but rather a carriaged, barrelled launcher for 88mm rockets. The Soviets transported these weapons back to the USSR for storage, but none were ever reissued as the RPG series of weapons filled it’s niche in the Cold War.

This Panzer IV, photographed several weeks after WWII ended in Europe, was knocked out inside Vienna, Austria during the war’s final days. Cleanup of heavy vehicles inside Vienna was hampered by the Soviet army 3rd Ukrainian Front’s hideous conduct after the fighting ended, which was so bad that Josef Stalin himself had to issue a directive for Soviet officers in Austria to regain control over their units.

(Imperial War Museum photo)

The above photo shows a German laborer in Berlin sorting stahlhelms during the summer of 1945. Most of the pile is the normal M35, M40, and M42 versions. The examples in the foreground, and in the worker’s hand, are the “M42 Beaded” version. The “bead” (the ring around the helmet) indicated a stahlhelm not approved for combat use. It’s debated today if the “bead” was added to regular production examples which failed their quality inspection, or, if it signified helmets intentionally made to a lesser standard for non-frontline issuance. These belonged to the Luftschutzwarndienst (air raid wardens) as indicated by the wings logo painted on the front.

The lone helmet in the lower left is interesting, it appears to be a Type BII, the prototype of what would have been the Waffen-SS’s M45. This was developed throughout WWII, before being presented to Hitler in late 1944, who rejected the design. The four or five dozen Type BIIs already made were sent to the Doeblitz Infantry School for use there. During the final battle in Berlin in April 1945, two understrength companies of infantry cadets from Doeblitz fought wearing Type BIIs. The Type BII is much better remembered as the basis of the M56, East Germany’s stahlhelm during the Cold War.

Meanwhile at roughly the same time on the other side of the world, a young Japanese hired by the US Army cleans and stacks M30-32 Tetsu-bo helmets.

Prefabricated steel matting was used by the Allies in both Europe and the Pacific, usually for aircraft runways but sometimes as road reinforcement. This 1947 photo shows French civilians collecting abandoned steel matting for sale to a scrapyard.

This Panzer III was photographed at a collection point in the American occupation zone in January 1946. It has a towing bridle attached, indicating that eight months after the end of the fighting, vehicles were still being cleaned up off battlefields.

Above, a GI hooks a tow rope to a Type 97 Te-Ke tank during cleanup of the Okinawa battlefields at the end of WWII in 1945.

Above, a PzKw V Panther sits along a Belgian road in 1947. Two years after the end of WWII, sights like this were declining but not altogether uncommon in western Europe. The Panther was eventually hauled away for scrap.

Another Panther in 1947, this one inside Germany. Local citizens had already removed any metal easily taken, including the tracks, roadwheels, and one of the exhaust covers.

(photo by David Seymour)

The former Omaha Beach in Normandy in 1947, two years after WWII and three years after the “Overlord” D-Day invasion there. Wreckage still litters the beach while offshore, some blockships of the Mulberry artificial harbor remain. The Mulberry had been abandoned after a 1944 storm. The incredible amount of combat debris on the invasion beaches was finally cleaned up by 1950. The remains of the Mulberry were slowly picked apart; by 2017 all that remains are several large concrete caissons. The beaches themselves have slowly been reclaimed; by 2016 the former Juno Beach was fully used for recreation.

One of the most interesting museums in Europe is Musee des Epaves in Port-en-Bessin, France. Founded by a local maritime salvor, it houses an amazing assortment of odd things fished out of the water off the Normandy coast. It is not strictly military but given Normandy’s history in WWII, there are a great many military items, including this M4 Sherman tank missed during the official post-WWII cleanup. The “Overlord”-related items range from the extreme to the mundane; for example a German torpedo to an American GI shaving kit.

Sometimes the unexpected turned up. These are Bachem Ba-349 Natters secured by the US Army in Austria at WWII’s end. The Ba-349 was one of Germany’s exotic weapons. Rocket-powered, it took off vertically from a launch pole, and was guided at near-transonic speed by an autopilot. At the last moment, the pilot took over and aligned the nose, which was filled with unguided rockets, at an enemy bomber. After the one-time attack, the Natter split in half. The engine parachuted down for re-use, the nose section was discarded, and the pilot (who was “spit out” of the open nose by inertia as the tail section parachute opened) separately parachuted to safety. Only 36 Ba-349s were built and only one flew one time, killing the pilot. As Germany crumbled, a small team from the Natter project set out on a bizarre trek across Bavaria, headed for the Alps with six Ba-349s on trailers. It’s still not exactly clear what their objective was, as there was no infrastructure there to launch Natters, nor pilots to fly them. In any case, the US Army found the aircraft in two groups; the ones above in an alpine pasture in Austria, during the war’s final week.

Perhaps a surprise to US Navy occupation forces in September 1945 was the wreck of IJN Iwate, a turn-of-the-century cruiser which had been bombed near Kure in 1945, not far from IJN Ise described further below. The wreck was raised in 1946 and scrapped in 1947.

Another unexpected find, this French FT-17 light tank was found at a former Luftwaffe base being used by the RAF in the British occupation zone of Germany in 1946. The little FT-17 served in both world wars, this example was most likely captured by the Germans in 1940. It was scrapped by the British.

Some battlefields were never fully cleaned up after WWII. A good example is the only WWII battlefield in North America, Alaska’s Aleutian Islands. These remote and inhospitable islands make recovery of heavy items nearly impossible and much equipment was just left there. Above is a Japanese Type A midget submarine which remains abandoned on Kiska island. Both Kiska and Attu, which were occupied by Japan, are uninhabited.

Isolated Pacific atolls and islands were similar. Like the Aleutians, it was very cost-ineffective (and in many cases, physically difficult) to move heavy or awkward scrap items off them after WWII. Almost all these islands had no industry and hence no internal demand for scrap iron. These small islands were placed into trusteeships, overseas commonwealths, etc after WWII and were low on the list of concerns for their guardian nation. In many cases, the Allies simply packed up and moved on after removing mines and UXO for the civilian population, with maybe a cursory cleanup. Further removal of war waste came slowly years or decades later, if ever. The photo above is a knocked-out Type 95 Ha-Go tank on Peleliu. This island was a Japanese possession before WWII, then administered directly by the US military from 1944-1947, then was lumped into the Pacific Islands Trust Territory until it joined the new nation of Palau in 1978. This tank, along with other wreckage of WWII, remains on the remote island as of 2017.

Pagan is a very remote Pacific island, with much of it’s area taken up by two active volcanoes. The pre-WWII population was 645 people; during the war Pagan was occupied unopposed by a 2,100+ strong Japanese invasion force. This was a mistake as the US Navy simply sealed off Pagan from resupply. The fighter detachment was either shot down or bombed, and eventually ran out of aviation fuel. By the time WWII ended, more than 500 Japanese troops had starved to death and the rest were suffering from malnutrition. After the war, Pagan was allocated to the USA’s Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands. The island has no pier for cargo vessels to moor to, so no war wreckage was removed after WWII. Due to the volcanoes, the last 100 residents fled Pagan in 1981 and the island now contains only the decaying remains of WWII, such as this A6M “Zero” fighter.

Taken in early 1948, the lawn of the shattered Reichstag is overgrown with weeds. Two and a half years after the end of the war, Berlin was still heavily damaged and held a significant number of wrecked WWII vehicles. In the corner is a Borgward Wanze, a remote-control demolition vehicle of the Wehrmacht which was pressed into service as a last-ditch anti-tank device during the battle of Berlin. The Reichstag sat in what became the British Sector of West Berlin, but it was right on the edge; the agreement with the Soviets set the boundary at the sidewalk immediately to it’s rear. Because of this, and because the destroyed building no longer had a political function, the area recovered more slowly than the rest of West Berlin.

Run in Life magazine in 1949, this photo shows a field of abandoned vehicles in Okinawa four years after the end of WWII. Some were leftover from the battle, others had been marshaled there for the planned invasion of the Japanese home islands which never happened. Much of the damage was inflicted not by war but by typhoon “Louise” shortly after Japan’s surrender.

(Imperial War Museum photo)

Literally the clipped wings of the Luftwaffe, this pile near Hanover in the autumn of 1945 was collected from all around northwestern Germany and Denmark, and shipped to Great Britain for recycling into consumer aluminum. Wings and tail fins were more ideal than whole planes as they could be laid flat and compacted into merchant ship holds.

(Imperial War Museum photo)

Photographed from a Ju-52 transport is an assembled field of Fw-190 fighters, many with propellers removed to prevent flight. This photo was taken in 1945, a month or two after the end of WWII, near the German city of Flensburg which sits 4 miles south of the Danish border. After Adolf Hitler’s suicide, his successor Admiral Karl Doenitz ran what remained of the Third Reich for 10 days out of the Mürwik Naval Academy at Flensburg. This interim is sometimes referred to as the “Flensburg regime”, and led to a concentration of surviving German military assets in the area before the final surrender. Flensburg fell into what became the British Zone and the RAF concentrated additional surrendered aircraft to the area for scrapping.

This carcass at the former Luftwaffe base at Chrudim, Czechoslovakia in late 1945 was once a Messerschmitt Me-323 Gigant transport. Despite it’s size, there was little salvage value in a Me-323. The six engines were an obsolete pre-WWII French design, and the fuselage and wings were largely wood and fabric over cheap alloy spars.

Sheep graze under a wrecked Fw-190 near Nuremberg during the summer of 1946, a year after WWII ended. During it’s final weeks, the Luftwaffe had dispersed many of it’s assets to any available flat grass field to evade Allied airstrikes.

Per a policy decision by General MacArthur, surrendered Japanese aircraft were to be immediately destroyed by the fastest possible method, usually immolation. Perhaps it seems a bit over the top today, but in 1945 there was serious concern about rogue Japanese pilots flying final kamikaze missions against occupation forces. Above, an American supervises surrendered Japanese personnel as they wrap gasoline-soaked tarps around the engines of a transport. Prior to demolition, the Japanese were supposed to paint green crosses over the rising sun roundel and/or remove the plane’s propeller; both instructions were obeyed to varying degrees.

It was decided (with some exceptions) against ferrying Japanese planes around; instead they would be destroyed where they stood. This was not easy; in the territories occupied by the USA (the home islands and southern half of Korea) there were about 300 facilities ranging from grass strips to major airbases, with one or more warplanes present in September 1945. The US Army’s 637th Tank Destroyer Battalion was very prolific, destroying about 1,500 Japanese aircraft in Honshu in the first half-month of the occupation. It’s methods were to hose parked planes down from a commandeered Japanese fueling truck driven past, or, to run over the planes with their tracked vehicles. Other units used infantry flamethrowers.

The photo above shows 200+ Japanese warplanes being burned by the US Marine Corps in late 1945 at Omura airbase in western Kyushu. The imperial army had planned to make this facility a centerpoint in the planned defense of the home islands (operation “Ketsugo”) and it was well-stocked with warplanes.

As time went on, and it became clear that the occupation was not going to be opposed, the policy was relaxed and aircraft were dismantled in a way more useful to civilian recycling instead of brute burning.

One Japanese warplane the USA was interested in was the Aichi B7A2 “Grace”, a high-performance carrier-based attack plane. The “Grace” outclassed it’s US Navy contemporaries and was actually faster than a “Zero” fighter. Only 114 were built during WWII, and only two Japanese carriers (IJN Taiho and IJN Shinano) had flight decks that could handle the “Grace”. Both were sunk before any could be stationed aboard, so the B7A2 was never used in it’s intended role and rarely encountered during WWII. This plane was transported to Maryland after Japan’s surrender for further study in 1946. The US Navy’s abandonment of horizontal torpedo attacks, and the dawn of the jet age, made the study irrelevant.

The Kawasaki Ki-48 “Lily” was one of the imperial army’s better tactical bombers. This example, collected in occupied Japan in October 1945, was briefly studied by the American military. The Ki-9 “Spruce” biplane ahead of it was burned immediately.

This field of abandoned Japanese warplanes in the Dutch East Indies was bombed by the Netherlands air force in 1946. A small but not trivial number of Japanese personnel allied themselves with Indonesian separatists at the end of WWII, including some pilots.

The nose of a Siebel Si-204 transport remains at the former Luftwaffe base at Stade, occupied Germany, in August 1946. The base was being used by the RAF at the time. As Allied personnel levels dropped, the pace of cleanup slowed in late 1946 and 1947.

At a collection point in Czechoslovakia, several Bf-109 fighters sit nose-down with a Ar-96 trainer and a Junkers W.34. Western Czechoslovakia had been one of the Luftwaffe’s last refuges in May 1945 and the country was littered with aircraft wrecks. The Junkers is interesting; it had served in the pre-WWII Czechoslovak air force and was then impounded by the Luftwaffe in 1938. The wings have been stripped off for the reasons described earlier.

Aichi E13A “Jake” seaplanes at RAF Seletar near Sembawang, Singapore after Japan’s 1945 surrender. This was a very critical base to Britain and clearing the airfield was more important than the aluminum scrap value, so the Japanese planes were bulldozed into a pile out of the way.

Two years later, with the Japanese aircraft gone, a Vultee Vengeance lies abandoned in a ditch at RAF Seletar. The UK was discarding so many WWII-era types so rapidly that there was a glut to scrap them, and often some ended up like this.

(photo by David Seymour)

When planes were shot down in WWII, the wreckage had to land somewhere. This B-24 Liberator’s wreckage still remained near Reims, France in 1947. Some of these downed planes, especially in remote areas such as Indochina or the Soviet arctic, were still extant in the 1950s.

Above is Klagefn airbase in Hungary several months after the end of WWII. The Hungarian air force had used Arado Ar-96 trainers during WWII, and at war’s end it inherited additional ex-Luftwaffe examples. The facility above was a cannibalization yard, by which Ar-96s were kept operational by salvaging spare parts from worn-out or broke-down examples. By this method, shrinking numbers of an original pool of about 110 Ar-96s was kept operational into the mid-1950s. In 1954 there were still a dozen of these ex-Luftwaffe planes in service. All non-Soviet equipment was purged from the Hungarian military after the failed 1956 uprising.

A Junkers Ju-388 night fighter sits partially-scrapped near Leipzig in June 1945, a month after Germany’s surrender. The US Army was retaining the nose section with it’s FuG 220 radar.

Similarly a Czechoslovak serviceman sits inside a Henschel Hs-129 tank-busting plane, one of the Luftwaffe types retained for post-WWII flight trials in Czechoslovakia. Behind it is a Junkers Ju-88 night fighter, being kept no doubt for it’s radar.

(Imperial War Museum photo)

The Völker Radiogerät (People’s Radio Set) was manufactured by Huth-Apparatebau in occupied Germany under Allied supervision during the late 1940s. It was a cheap civilian radio receiver that recycled components of WWII German military radios.

Cleaning up all of the UXO (unexploded ammunition) in Europe after WWII was a job far outside the scope of this article and one still ongoing; for example a Luftwaffe bomb from the Blitz was found in downtown London in January 2017. In the immediate postwar era, the most pressing concerns were clearing urban areas and highways, and, “bulk” demolition of unwanted munitions to minimize / eliminate the hazards of moving them around the continent. Above, with the shattered Reichstag behind them, Soviet navy Rear Admiral Ivanovich Krylov commends an EOD diver clearing the Spree River in downtown Berlin in 1945. Judging by Krylov’s coat and the diver’s cold-weather drysuit, this was probably in the autumn or early winter of 1945, several months after the end of WWII.

In the British zone of occupied Germany, a Royal Air Force EOD specialist prepares a pile of Luftwaffe SC-250 551 lbs bombs for demolition during the summer of 1945.

On the other side of the new “Iron Curtain”, Luftwaffe AB-250 cluster munitions are lined up for demolition by a Soviet EOD team in Czechoslovakia in late 1945.

(Imperial War Museum photo)

Above, German POWs in Belgium sort WWII small arms ammunition for recycling during the winter of 1945-1946. The ammunition was first baked in a furnace to “shoot” it, then after cooling the tumbler separated the lead bullets from the brass or steel casings.

Far more difficult to handle was surrendered chemical weapons. All combatant countries, both Axis and Allied, stockpiled chemical weapons for expected massive gas attacks which thankfully never came during WWII.

There were several methods employed to dispose of Germany’s massive stockpile. The safest, and most difficult and expensive, is shown above at St. Georgen, Germany in June 1946, a little over a year after Germany’s surrender. German workers in Luftwaffe-issue gas masks are pumping out mustard gas (HD in the modern US Army code) from Luftwaffe 500 lbs gas bombs. The mustard gas (which despite it’s name is actually a liquid misted at detonation) was then inerted by a specialist US Army team while the empty bombs were decontaminated and melted as scrap.

A more common method is shown above in 1946. This was at a former Wehrmacht munitionsarbeitshäuser (ammunition facility, or MunA) at Feucht near Nuremberg in the American occupation zone. The US Army made this facility a centralized site for destroying chemical artillery shells and light bombs, done by building earthen crucibles as shown above and incinerating the ordnance. This was obviously dangerous (four German workers were killed) but a fast and cheap method of eliminating chemical weapons. The Feucht facility also handled regular dud aircraft bombs found inside Nuremberg, and small arms ammunition from the surrounding countryside.

When West German sovereignty was restored in 1949, the Third Reich’s chemical stockpile was gone but the Feucht facility’s infrastructure for handling such a wide variety of ammunition made it ideal to NATO. It was redesignated Feucht Ammunition Storage Area (FASA) by the US Army. FASA lacked atomic warheads but was said in the 1970s and 1980s to store “anything short of a nuke” implying the alliance’s own chemical weapons. When the Cold War ended, the US Army turned FASA over to the Bundeswehr which eventually closed it. In 2006 the soil was found to be contaminated with arsenic residue from the post-WWII chemical incinerations along with lead from conventional ammunition.

The quickest and cheapest method at the time, and most problematic today, is shown above as Royal Navy personnel supervise the mass dumping of bulk storage tanks of German chemical weapons into the North Sea.

There were five main sea dumping areas: one in the deep North Sea; one in the Belts south of Norway; the “main” east site which was in the deep eastern Baltic Sea roughly equidistant from East Prussia, Sweden, and Latvia; the other east site off Denmark’s Bornholm island; and finally a shallow-water site in the Baltic near Kiel.

The Kiel site was used by the Germans themselves in the time of the brief Flensburg government, then later by the British, and was the smallest and of least concern today.

The two North Sea dumping sites were done mainly by the Royal Navy in the summers of 1945 and 1946. For the most part, the material dumped was bulk-storage containers of chemical weapons not yet loaded into shells or bombs, and also any form of Germany’s new nerve agents. Tabun (GA), sarin (GB), and soman (GD) nerve gas was maybe Germany’s best kept secret; the Allies did not even know of them until the Soviet army overran a stockpile in early 1945. Tabun and soman are ultra-lethal and behave much differently than mustard gas (HD) or phosgene (CG). Less samples taken for copying, the western allies dumped as much of this as possible into the sea as fast as possible. Today, the deep North Sea site is, apparently, not an issue but the Norwegian and Danish governments are both concerned about the Belts dump site, which is in less than 2,000′ deep water. Most of the dumping here was by scuttling barges or inoperable cargo ships; of the 36 known craft the Norwegians consider 15 to be a risk.

A much more serious problem has been the two east sites, which were used almost exclusively by the USSR after Germany’s surrender. About 40,000 tons of chemical weapons (with 15,000 tons of the actual chemicals) were dumped there between 1945-1949. The “main” east site, which was agreed upon by all the Allies prior to the end of WWII, is in deeper water compared to the Bornholm site. Bornholm, a Danish island, was briefly administered by the USSR in 1945-1946 and used as an alternate site.

For both sites, the Soviets used designated embarkation ports: Wolgast, Stettin (today Szczecin, Poland), and Danzig (Gdansk, Poland) in their occupation zone of Germany and Libau (Liepâja, Latvia) further east. In addition to the common HD, CG, and CI agents, the Soviets also captured large quantities of GB, GA, and GD as they overran Silesia in 1945. This was a bonus to Stalin’s Cold War chemical weapons program but a headache at the time.

At sea the chemical weapons were either hand-dumped one by one, hand-dumped by the pallet, or loaded onto wrecked German ships which were then scuttled at the dump sites. All of the methods had issues. En route, sometimes chemical weapons were jettisoned by the crew to lighten the ship during storms. A number of the decrepit scuttling candidates sank altogether en route. At the dump sites, hand-dumping was labor-intensive, while dumping whole wooden crates caused a “slow sink” where ordnance would drift laterally on the way down instead of quickly going to the bottom.

As the Soviet program went on, they increasingly routed dumps to the Bornholm site as too many ships were foundering on the way to the main eastern location. The Bornholm site received many more tons than had been planned. There are strong currents in this area and German chemical weapons have been found as close as 10 miles off Sweden and 40 miles off Poland, meanwhile on Bornholm itself, chemical weapons sometimes actually wash ashore.

Throughout the Cold War, there were usually three of four instances a year of Baltic fishermen snagging dumped chemical weapons in these sites. This changed between 1989-1992 when there were 160 incidents in 36 months. The spike was due to changed fishing patterns: the East German restricted areas had vanished completely and Polish fishermen were netting further north.

The situation in the Far East in 1945 was quite different. Japan’s chemical stockpile was smaller and less sophisticated than Germany’s; on the other hand, (along with Italy) Japan was one of two nations to use chemical weapons during WWII and by far and away the most prolific user. Japanese use of chemical weapons against China is well-documented (including actual photographic evidence during the occupation of Shanghai) and estimated to have cost China 10,000 casualties. Japan’s chemical warfare program was largely outside of the home islands, and centered at Unit 516 at Cicigar in the puppet nation of Manchukuo (today Qiqihar, China). Unit 516 was subordinate to Unit 731, the overall imperial special weapons outfit more famous for it’s gruesome biological warfare experiments.

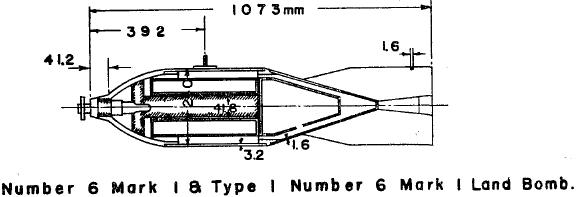

The above drawing of a Japanese chemical bomb was prepared by the US Navy in 1945. The types of chemical weapons were lewisite (L in the modern US Army code), mustard gas (HD), phosgene (CG), and cyanide (AC) along with (actually, most commonly) an agent the imperial army called “yellow gas”, a cocktail of HD and L. Over 2 million bombs and artillery shells were manufactured.

On 9 August 1945, the same day as the Nagasaki atomic mission, the USSR invaded Japan’s puppet state of Manchukuo and northern Korea. Some of the Japanese chemical stockpile was captured intact. Opposite their policy in Europe, the Soviets did not retain or study the Japanese chemical weapons. Initially, Stalin refused to transfer any to Mao’s communists and ordered it all destroyed. However years later, as the red army completed it’s pullout from Manchuria, some Soviet-made chemical weapons were transferred to Mao’s troops. During the 1980s the PRC army’s chemical weapons stockpile included modern Chinese manufacture, alongside aging WWII-era Soviet and Japanese ordnance, so either some was inadvertently transferred, or, the Chinese themselves recovered and refurbished some.

After the Emperor’s 15 August 1945 surrender announcement, orders were issued to forces on the Asian mainland to destroy in situ any and all chemical weapons in their possession. Some units in Manchukuo possessing chemical rounds were already in motion due to the Soviet attack. None were properly destroyed, many were thrown into Manchuria’s Nen river, others were buried wherever the possessing unit happened to be at the time. This led to a scattershot effect as small quantities (sometimes one or two individual shells) was buried along the side of a road, in a culvert, or wherever. By intent, none of the locations were marked.

When China’s building boom started in the 1980s this increasingly caused problems as workers in formerly rural areas struck long-buried chemical weapons. Due to the haphazard way Japan’s chemical warfare effort ended, these ranged in quantity from lone individual mortar rounds, up to (for example) a find in April 2001 of 193 artillery shells and four 55 gallon drums in one location.

Between 1999-2005, a total of 281 WWII Japanese chemical weapon items (artillery shells and bombs) were recovered in China at Japanese expense, in addition to those China itself had been storing, in some cases since the 1950s. By the end of 2013 about 50,000 items had been destroyed. In January 2017 another 2,500 items were destroyed. The estimate of what remains unaccounted for in 2017 is an item of dispute; Japan feels between 200,000 to 300,000 items while China has quoted figures as high as half a million.

Sea mines were another issue. Hundreds of thousands of sea mines were laid during WWII; the Royal Navy alone laid over 100,000 in a stretch from Scotland to Iceland. Overall it was estimated that 600,000 sea mines had been laid in the European theatre. After WWII, the western Allies in Europe, and the USA in occupied Japan, enlisted their former enemies in clearing these minefields to lessen the danger to their own sailors.

The Kriegsmarine’s converted fishing trawler KUJ-12 survived WWII and was disarmed and used by the German Mine-Sweeping Administration, or GMSA. Formed in 1945, this civil service used surrendered German sailors and ex-Kreigsmarine vessels to sweep the North and Baltic seas. GMSA ships flew the #8 signal pennant as an ensign, as Germany was no longer a sovereign nation. The GMSA sailors received a salary and continued to wear their Kreigsmarine uniform (less any nazi insignia) until they wore out, at which time they adopted surplus Allied naval uniforms. From June 1945 until it’s disestablishment in January 1948, 2,721 mines were swept (a small fraction of those laid) and 10 GMSA ships were sunk by mines.

In all theatres of the war, the number of naval mines swept after 1945 paled in comparison to those laid during WWII. Even in the late 1950s some areas of the North Sea were still dangerous, and during the 1975 American evacuation of the Saigon embassy, US Navy charts showing China’s Hainan Island region had a notice-to-mariners that WWII sea mines were still believed in the area.

Above is a British Mk.XVII mine being inspected by an EOD specialist of the Icelandic coast guard in 2016. Many WWII British moored mines had a safety that if the chain between the mine and anchor broke, the released tension would disarm the mine, which would then float until barnacle growth caused it to be negatively buoyant, at which time it would sink to be destroyed by sea pressure. To the dismay of post-WWII Iceland, currents often carried floating mines to Iceland’s rocky coast, where “tails” of rusted-through chains snagged rocks, causing the mine to pop up and regain tension, rearming itself. Even dead WWII mines with their contact horns gone present a danger in Iceland, as deep currents rolled sunken mines ashore over many decades, with the small bursting charge inside undamaged by sea pressure.

The modern Pacific nation of Kiribati, site of the Tarawa and Makin battles during WWII, found this WWII American Mk6 mine in June 2014. The Mk6 was a moored floating mine, here the anchor chain is long since rusted away and the sunken mine itself completely crusted over with coral. Unlike the deep Atlantic, many mines in the Pacific were laid in shallow areas and present more of a modern danger. This particular one was destroyed by an Australian EOD team.

Above, the Admiral Scheer lays capsized in Kiel, occupied Germany, in May 1945 near two never-completed u-boats. The most successful of Germany’s three “pocket battleships”, Admiral Scheer was attacked pierside by five 12,000 lbs Tallboy bombs during a RAF air raid on 9 April 1945 and capsized. Only 21 days before Hitler’s suicide, the sea war was over by that point but the British targeted Admiral Scheer to produce one fewer warship the Soviets might try to claim after Germany’s surrender.

In July 1945, British occupation forces authorized scrapping of the capsized wreck, which started in October 1945. Working from the “bottom down”, scrappers removed the propellers (of solid manganese bronze) and much of the hull. As work neared the waterline, the wreck was slightly rolled, so that some items above the waterline could be removed. By July 1946, as much as possible had been done and for several years the hulk sat in economic limbo: it was impossible to scrap any more on site, but, what remained would not cover the costs of a specialist tow to a graving dock.

In 1949, a decision was made to eliminate the area of the harbor where the Admiral Scheer wreck was at. This section of the naval base was artificial, resembling a square connected by a narrow channel to the main harbor. At the time, as West German sovereignty was being restored, the country had not yet rearmed and there was no reason to believe there would ever be a German navy again. Starting in late 1949 the channel was cofferdammed off and the area drained, and then filled in with dredged sea sand and rubble from bombed-out areas of Kiel. With this, the wreck of Admiral Scheer was buried under thousands of tons of debris. There are the remains of 15 crewmen still inside.

No ceremony or marking was done for the wreck as it was covered with rubble. In 1978 the Kieler Nachrichten newspaper pinpointed the location, which is inside the new Kiel Naval Arsenal. For many years it was said to be under the parking lot shown above, but with GPS and satellite imagery it’s now thought to be directly under the line of trees and brown grass just slightly to the parking lot’s southeast, in the above image’s center.

(photo via Navsource website)

Above, USS Baretta (AN-41) and USS Catclaw (AN-60) heave the wreck of a Japanese Type C midget submarine out of Untan Ro harbor on Okinawa in September 1945, at the end of WWII. Their intended task now done, the US Navy’s netlayers were very busy in late 1945 and throughout 1946 removing Japanese mooring buoys and clearing light wrecks, all across the Pacific.

Meanwhile in Europe, the US Army watercraft corps tug LT-214 helped clean up ports in France, the Netherlands, and occupied Germany from 1945-1948.

The above photo shows a pair of bombed u-boats in Hamburg harbor during the summer of 1945. Hamburg lay inside the British occupation zone and the UK, especially the Royal Navy, was in no hurry to make the military area of the port functional again.

(Bundesarchiv photo)

The above photo is Hamburg in August 1948, three and a half years after WWII. Beginning in 1946, the occupying western allies began a “deindustrialization” effort in their zones, to prevent any future German nation from ever becoming a military power again. This continued until West Germany regained sovereignty in 1949. In retrospect, the effort was a failure, as it’s tertiary effects caused recessions in other European countries. As part of the “deindustrialization”, the British prohibited clean-up of Hamburg’s port (the Blohm + Voss u-boat shipyard is shown in the photo) and in some cases, ordered additional demolition of buildings that had escaped Allied bombing.

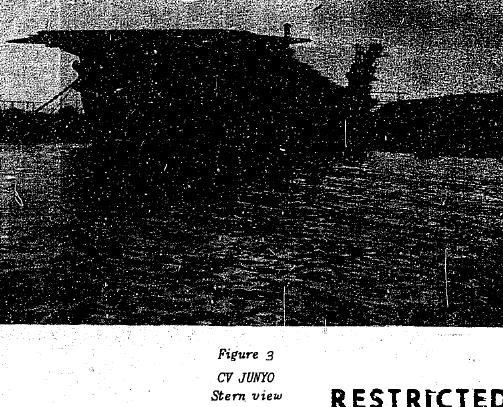

Above, IJN Ha-210 rests alongside IJN Junyo along with another surrendered submarine in October 1945, a month after WWII’s end. Unlike the trilateral negotiations for the awarding of surviving German u-boats, General MacArthur viewed surrendered Japanese subs as America’s alone to disposition and all were scuttled or scrapped to forestall any claim by the USSR.

The transport submarine IJN I-352 being scrapped in January 1948, two and half years after WWII. Per General MacArthur’s directive no IJN submarine survived; all were scrapped or scuttled. Designated Sen-Ho by the Japanese, IJN I-352 and her sister IJN I-351 were supposed to be covert refuelers of seaplanes but ended up as blockade runners, bringing crude oil to the home islands and refined fuel outbound. Only two were built before the project was cancelled; IJN I-351 was sunk in a sub-vs-sub encounter by USS Bluefish (SS-222).

IJN Junyo was a veteran of the Guadalcanal and Aleutians operations. On 9 December 1944, IJN Junyo was torpedoed by USS Redfish (SS-395) and limped to Sasebo Naval Yard, where the carrier was drydocked. Because of the imperial navy’s severe aircraft and fuel shortage, it was decided not to repair IJN Junyo and the hull was patched so that suicide craft and midget submarines could be assembled inside the drydock. With inoperable engines, IJN Junyo was towed to Ebisu Bay, about 4 miles south of Sasebo.

WWII ended on 2 September 1945 but the first American personnel did not board IJN Junyo until 8 October 1945. An inspection team toured the carrier in November 1945, when the photo above was taken. Externally there was no damage however internally, the torpedo hit had completely destroyed the starboard side of the engine room and damaged the port side. An item of interest was a 30-tubed launcher for 5″ rockets, a sign of how desperate the Japanese had been to try any idea against American air power.

As the carrier was otherwise undamaged less the engines, IJN Junyo was towed by the US Navy to Sasebo Naval Yard and used as a makeshift tender and station vessel for smaller surrendered and salvaged Japanese warships during 1946. On 1 June 1946, tugs pushed the carrier pierside for scrapping, which completed on 1 August 1946. The only surviving article is the ship’s bell, which was given to Fordham University by the US Navy.

Above is the port of Toulon, France in 1952, seven years after the end of WWII. The city had been rebuilt by this time, but like a dead whale in the harbor is the French fast battleship Dunkerque. Along with her sister-ship Strasbourg, Dunkerque was a creative design, packing as much punch as a heavy cruiser but with better speed, range, and armor; while staying in the limits of inter-war naval limitation treaties. Neither battleship accomplished anything during WWII. Strasbourg was damaged in 1940, scuttled in 1942, raised, sunk again by American aircraft, and broken up after WWII. Dunkerque was massively damaged by HMS Hood and a Royal Navy airstrike during the attack on the Vichy fleet at Mers-el-Kébir in July 1940. The patched-up Dunkerque finally returned to Toulon in February 1942, only to be scuttled several months later. The Italian navy raised the hulk to salvage which was then bombed again by American aircraft, upon which time Dunkerque was written off and scrapping continued. This had not been completed by the time the Allies liberated Toulon. The postwar French navy assigned the hull number Q56 to the Dunkerque wreck, which was picked apart piecemeal after WWII.

The port of Toulon was an absolute mess at WWII’s end, full of UXO and wrecks; most coming from the mass scuttling on 27 November 1942. Ships involved included the old battleship Provence, both Dunkerque class fast battleships, the heavy cruiser Algérie, a half-dozen other cruisers, and a variety of smaller warships. The issue was compounded by the fact that the Italians and Germans raised (or partially raised) some ships to salvage off them, in some cases moving the hulls and worsening the situation from a later clean-up perspective. In turn the Allies had bombed many of the raised hulks later in WWII, making them even more difficult to move afterwards.

Above is how the Allies found the heavily-damaged, raised, and partially-scrapped hulk of Dunkerque when they liberated Toulon. It was barely recognizable.

The first of the large ships to be cleaned up was the capsized light cruiser Marseillaise, which completed scrapping in 1947, followed by the heavy cruiser Colbert in 1948 and the old battleship Provence in 1949. The heavy cruiser Dupleix was finally scrapped in 1951. The light cruiser La Galissonniére was scrapped in 1952; besides itself being a nuisance the La Galissonniére wreck hampered access to some other hulks including Dunkerque. The Strasbourg wreck was finally scrapped in 1955, and last of all was Dunkerque, which did not complete scrapping until late 1958.

The above photo shows the partially-raised, half-scrapped wreck of the German battleship Gneisenau in November 1949, four and a half years after the Germans scuttled the ship at Gotenhafen, East Prussia (today Gdynia, Poland). The scuttling was masterful and fully blocked the harbor, and also positioned the hulk in a way that it was difficult to raise. Scrapping did not complete until 1951.

IJN Ise was one of two battleships converted into hybrid half-aircraft carriers during WWII. The aft main turrets were replaced with a rump flight deck, one elevator to a hangar deck below, and two catapults. Up to 22 planes could be carried. The hybrid project was a failure. There were never enough planes or pilots available, and the two hybrids usually went to sea with few or no aircraft. The changes made them weak battleships. IJN Ise later had the catapults removed and was used to import raw materials to the home islands in her empty hangar. The photo above is an American reconnaissance photo after the emperor’s surrender broadcast. IJN Ise was attacked three times in June/July 1945, taking 20 bomb hits. IJN Ise sank in very shallow water at Ondo Seto near Kure, gutted and nearly splitting in half at the forward edge of the flight deck, and on a 15° starboard list.

Cleaning up the wreck of IJN Ise was a challenge due to the wreck’s weight, heavy damage, and proximity to shore. After an inspection by the US Navy Technical Mission to Japan (NavTechJap) in mid-November 1945, work slowly began on stabilizing and partially dewatering the wreck. As seen above, a floating causeway was built to carry a pipeline and power from shore.

IJN Ise sank at a location inbetween the Japanese mainland of Honshu and Kurahashi island, itself seated midway between Honshu and Shikoku. Moving the wreck to one of Kure’s eastern shipyards was judged too dangerous as it would block shipping if it broke up. This eliminated Ishikawajima Shipyard, which taken over the surviving assets of waterfront portion of Kure Naval Arsenal including the two Yamato-sized drydocks which would have been ideal. Kegoya Dock Company in Kure (formed during the Occupation specifically to scrap ships) was overbooked and Imbari Shipyard too far away and too small. For about a year after WWII, little was done with the wreck other than piecemeal salvaging.

In 1946 workers from Harima Zosen shipyard were instructed to scrap the wreck in place. Some of the personnel had previous experience with submarine building during WWII, which was maybe judged useful to the half-sunken IJN Ise. The wreck was stripped down the superstructure, secondary armament, and flight deck. This started in October 1946 and once accomplished, the remainder of the hull was buoyed up and broken apart for further recycling ashore. The last recognizable pieces of IJN Ise were retrieved in June 1947.

(US Air Force archives photo)

Taken in February 1946, this partially-flooded bombed drydock at Kure Naval Arsenal holds no fewer than 36 uncompleted midget submarines of the Type D “Koryu” class. The scrapping of wrecked and salvaged ex-IJN warships was hampered by the massive destruction to Japan’s shipyards during WWII. Kure Naval Arsenal lost 70% of it’s buildings and cranes, and over 1,000 trained employees to American bombing. This particular drydock was drained later in 1946 and used as a scrap metal dump. It was not emptied out until the late 1940s.

Taken several months earlier, this photo shows the damaged Mitsubishi shipyard at Nagasaki, with incomplete Type D midget submarines untouched since the morning of 9 August 1945.

IJN Ibuki was supposed to be the leadship of a cruiser class. During WWII the Japanese ordered the hull converted into a light aircraft carrier and the rest of the class cancelled. By early 1945, the conversion was at least half a year behind schedule and on 16 March 1945, the effort was halted as there was now no way it could be finished before the estimated time of the USA’s invasion of the home islands. At the time IJN Ibuki was structurally complete and 80% fitted out.

In November 1945, US Navy personnel studied IJN Ibuki. There was nothing to be learned from the design but it was noted that the hull was undamaged and had good reserve buoyancy as it was missing equipment weight; furthermore it was free of any ammunition or fuel and thus a low fire hazard. The never-finished carrier was placed at the bottom of the disposal list for large ships as it was low-risk storage.

During the spring of 1947, IJN Ibuki was acquired by Sasebo Heavy Industries, now the civilian owner of the old imperial naval yard areas not taken over by the US Navy. The photo above shows the wreck drydocked in March 1947. Throughout the summer the incomplete carrier was scrapped, finishing on 1 August 1947.

In the USA, the post-WWII scrapping of retired US Navy warships was a great financial boon, both in profit to scrapyards and sale revenue to the federal government. The situation was far different in occupied Japan with the IJN’s damaged wrecks. There was a critical shortage of carbide and acetylene, which had to be imported at steep prices. The decrepit wrecks themselves were difficult and expensive to handle. Especially in early 1946, there was a glut of unprocessed raw scrap with little production demand on the other end. Ships like IJN Ibuki were scrapped at a significant loss using peacetime accounting methods.

Similarly, the cruiser IJN Oyodo, which had been hit by eight bombs and sunk in July 1945, was an unprofitable scrapping when the wreck was finally raised in late 1947. The remains of the ship were broken up at Kure in 1947-1948.

This surrendered Type 101 landing ship was used by the US Navy in the cleanup of Kure harbor, shown here ferrying never-completed Kairyu class midget submarines to a scrap collection area. The 2-man, 20-ton Kairyu was intended to carry two torpedoes and a nose cone with either ballast or a TNT charge. By the time mass production started, plans to train crews on torpedo attacks were cancelled and the Kairyu became a de facto suicide weapon, sinking ships by ramming them with the TNT-filled nose. A total of 760 were ordered during WWII of which only 200 were built with another 14 incomplete, like these. None ever saw combat. The landing ship shown was itself scrapped in 1947.

A kilted infantryman of a British highlander unit inspects a Molch midget submarine during the summer of 1945. The Molch was the least successful of Germany’s midget submarine designs. This one was trucked overland to Stavanger, Norway for sale to a scrapper.

Sister-ship of IJN Ise, IJN Hyuga sits wrecked about a month after the end of WWII. Already without aircraft and short of fuel, IJN Hyuga was hit by dive bombers off USS Wasp (CV-18) on 19 March 1945 knocking out half the propulsion lineup. The crippled hybrid was pounded by aircraft off a half-dozen American carriers during July 1945. During an air raid on 24 July 1945, IJN Hyuga‘s captain, Rear Admiral Kusagawa Kiyoshi, knew his ship would not survive and ordered best available power to move a short distance above sandy shallows. The Japanese captain was killed by a bomb hit to IJN Hyuga‘s bridge but his order was carried out and the wrecked IJN Hyuga settled on an even keel in extremely shallow water.

IJN Huyga was located at a place called Nasake Jima, about 15 miles away from Kure naval base itself. The hull completely flooded out below the weather deck and thus US Navy efforts to study the wreck were limited; especially as a technical team had visited the IJN Ise wreck several days before. The above photo was taken on 30 November 1945 by a US Navy team and illustrates how the first bomb blew the vessel’s bow off.

The flight deck took several bomb hits and collapsed under it’s own weight as the hangar deck below flooded out. The rails in the above photo allowed movement of planes on the rump flight deck. The cracked pavement in the photo was poured concrete. This was not for armoring. Surrendered Japanese sailors told the US Navy that the conversion from battleship to hybrid seriously shifted the centre-of-gravity and the concrete was added as ballast. Beginning in July 1946, IJN Hyuga was stripped of weight, buoyed up, and slowly towed to Harima Zosen shipyard in Kure for scrapping, a difficult task. This was completed on 4 July 1947.

As the backlog at Kure’s drydocks evened out, less critical jobs could be taken on. The wrecked cruiser IJN Tone, which had been sunk at Ita Jima during the summer of 1945, was raised in 1947, towed to Kure and scrapped in 1948. It was the last 3,000+ tons IJN warship scrapped.

The cruiser IJN Takao was crippled by two torpedoes from USS Darter (SS-227) during WWII and never repaired. The ship was derelict in Singapore when WWII ended. The Royal Navy had a backlog of jobs for Singaporean shipyards, and there was no time to scrap IJN Takao. The inoperable cruiser was towed to deep water and sunk by gunfire of HMS Newfoundland in October 1946.

The belly-up battleship Tirpitz, sunk by the RAF at Håkøya, Norway during WWII, was scrapped upside down in the fjord between 1947-1949. Initially a floating crane was brought alongside to heave heavy portions off and onto alongside cargo ships. Lighter portions were moved by hand as shown above. As the waterline was approached, a salvage platform was built alongside. Submerged portions were finally heaved up by crane between 1950-1957. Today scattered pieces of the battleship still remain on the seafloor and the decaying salvage platform is visible at low tide.

The Imperial Japanese Navy object above is, depending on which part of the world you are from, known as either a doughnut buoy or dumb lighter, and was essentially a floating fuel storage tank. The Japanese called them “cargo pipes” and had several varieties, including some towed by submarines. When Japan surrendered in 1945 this one was abandoned at the island of New Britain, today in the country of Papua New Guinea. It was still extant in 1972, 27 years after WWII.

Some of WWII’s specialized structures were removed after the war. The Zoo Flakturm was a fortified anti-aircraft tower in downtown Berlin, and one of several such structures around Germany. In 1947 (lefthand photo), the Allies made only a partially successful attempt to demolish it by dynamite. The ruins were broken up slowly, as seen in the 1955 (righthand) photo. The difficulty in demolishing this flak tower led to many of the others being left alone after WWII.

Above, a British soldier attaches fuze cord to a Luftwaffe SC-250 bomb inside the “Killian” u-boat shelter in Kiel. On 25 October 1945, the Royal Navy detonated 107 such bombs inside “Killian” collapsing it. This killed two birds with one stone; demolishing the naval facility and ridding the RAF of unwanted enemy ordnance. The nearby “Konrad” shelter received similar treatment in 1946. Neither shelter was fully destroyed. West Germany finished demolition of “Konrad” in the 1960s. Meanwhile, the gigantic “Killian”s ruins still existed until 2002.

The Admiralty Citadel was built in London during WWII as a last stand for the Royal Navy if Germany invaded. The bombproof, bunker-like building has sites for anti-tank weapons and machine guns. The building is adjacent to the old Admiralty (which can be seen in the right corner of the photo) at the Queen’s Horse Parade in the Whitehall area of London. After WWII, there was no way to demolish such a structure due to the classical buildings nearby. It was left intact. The above photo was taken on Christmas Day 2016 and shows it’s current state, covered with transplanted Boston ivy to give it a less menacing look.

No look at this topic would be complete without mentioning perhaps the most difficult cleanup task of all, the scrapping of IJN Amagi. This 22,534t displacement aircraft carrier commissioned on 10 August 1944 but due to the imperial navy’s severe shortage of warplanes and pilots, never received an air wing.

After the failed “Ten-Go” operation in April 1945 and the loss of IJN Yamato, the imperial navy decided to throw all resources into a planned final defense of the home islands using submarines, kamikazes, and suicide boats. There was no longer any need for aircraft carriers and IJN Amagi decommissioned. The carrier was anchored 50 yards off the southern tip of Mitsukojima, a tiny island off Ondocho 5 miles south of Kure.

As late as the summer of 1945, many Japanese officers hoped WWII would end with some sort of armistice or cease-fire, as opposed to an unconditional surrender of the empire. To that end, IJN Amagi was to be part of a postwar imperial navy, and the carrier was camouflaged with false rooftops and streets painted on the flight deck. This was unsuccessful, as on 24 July 1945, US Navy planes hit IJN Amagi with two heavy bombs and a rocket, completely destroying the elevators and flight deck and starting slow flooding internally. Over the next three days the ship took on more water. On 28 July, another massive air raid scored more direct hits and started a fire which was put out by firemen ashore. The crew by this time had abandoned ship. Overnight, IJN Amagi slowly began to list and at 10:00 on 29 July, IJN Amagi snapped hard to port and capsized at a severe 70° angle. The elevators fell out into the water, and the entire flight deck bent it’s supports and shifted left and downwards.

American occupation forces arrived at Mitsukojima on 13 October 1945. In late November, a NavTechJap team inspected the wreck. It was determined that the capsizing was caused by firefighting water draining too slowly and making the ship topheavy, combined with asymmetric flooding in the boiler rooms and general cumulative damage. One interesting thing found was a document prohibiting the ship from exceeding 12 kts due to Japan’s severe fuel shortage.

It was clear at the end of 1945 that cleaning up the IJN Amagi wreck was going to be a massive undertaking, on par with raising the sunken Pearl Harbor battleships during the war, albeit that here there was no need to repair the carrier. On 16 February 1946, the US Navy authorized salvage of the wreck however there was still no clear plan. Several times American occupation personnel heard metallic groans, indicating stresses on the hull were still shifting. Throughout the spring of 1946 several unsuccessful attempts were made to roll the capsized hull. The blown-open elevators acted like scoops, filling the hangar deck with seawater faster than it could drain out of damage holes, rolling the ship back to where it was.

Meanwhile, Mitsukokima island, which had taken many misses intended for IJN Amagi, was cleaned up. Before WWII, it had been a quarantine barracks. After the occupation it was stripped flat and today in 2017 is used to store a massive pile of industrial salt.

In the late summer of 1946, US Navy specialists and surrendered Japanese personnel used dynamite charges inside the starboard side of IJN Amagi‘s hangar deck to sever the wrecked flight deck’s supports and allow it to slide off into the harbor. This done, the hull was slowly rolled in November. On 5 December 1946, the wreck was once again on an even keep and dewatered enough to clear the seafloor. Carefully throughout early 1947, the wreck was lightened by stripping in place, and eventually towed to Kure, where the rest was dismantled. IJN Amagi ceased to exist on 12 December 1947, the end of an exceptionally difficult job.