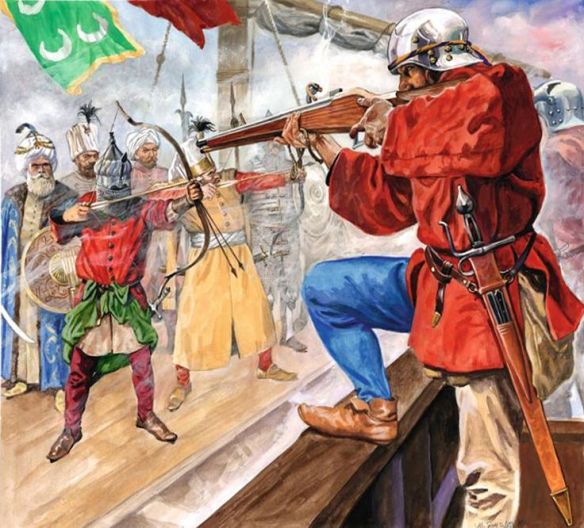

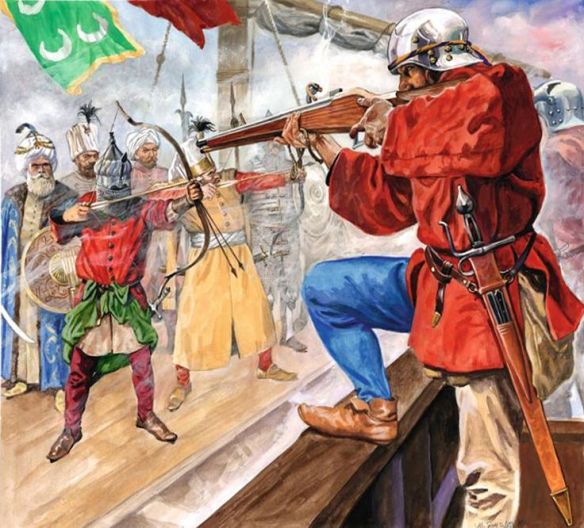

1568. Battle of Jemmingen. Spanish arquebusiers. Angel García Pinto for Desperta Ferro magazine

Gonzalo de Córdoba, (1453-1515).

“el Gran Capitan.” Castilian general who reformed the tercios, reducing reliance on polearms and bringing more guns to reinforced pike formations that could operate independently because of their increased firepower. He fought in Castile’s civil war that attended the ascension of Isabel to the throne. Next, he fought in the long war to conquer Granada. He was sent to Naples from 1495 to 1498 to stop the French conquest. He lost to Swiss mercenary infantry at Seminara, but adjusted his strategy and slowly pushed the French out of southern Italy.

He used the same tactics in Italy that worked in Granada: progressive erosion of the enemy’s hold over outposts and the countryside, blockading garrisons, and avoiding pitched battles where he could. He fought the Swiss again, and won, at Cerignola (1503), handing them their first battle loss in 200 years.

He beat them again that year at their encampment on the Garigliano River. Between fighting the French and Swiss he fought rebellious Moriscos in Granada and against the Ottomans in behalf of Spain and in alliance with Venice. He retired in 1506, well-regarded as a great general of pike and arquebus warfare.

tercio.

“Third.” The name derived from the tripartite division common to early modern infantry squares, especially the main infantry unit in the 15th-16th-century Spanish system. Tercios started at 3,000 men, but heavy tercios could have up to 6,000 men each, formed into 50 to 60 ranks with 80 men to a file.

They were super-heavy units of armored and tactically disciplined pikemen, supported by arquebusiers and lesser numbers of heavy musketeers on the corners. To contemporary observers they appeared as “iron cornfields” which won through shock and sheer mass rather than clever maneuver.

Others saw in the tercio a “walking citadel” whose corner guards of clustered arquebusiers gave it the appearance of a mobile castle with four turrets, especially after the reforms introduced by Gonzalo de Córdoba from 1500. He wanted the tercios to better contend with the Swiss so he added more pikes at the front but also many more gunmen to replace the older reliance on polearms.

These formations might have only 1,200 men. The new tercio was still heavy and ponderous on the move, but it was a more flexible unit with much greater firepower that could dig in for defense or advance to destroy the enemy’s main force as circumstances suggested.

This reform first paid off at Cerignola (1503). At Pavia (1525), tercios destroyed the French under Francis I. For two generations after that most opponents declined battle against the tercios whenever possible, and they became the most feared infantry in Europe.

They remained dominant for nearly a hundred years. Their demise came during the Thirty Years’ War when more flexible Dutch and Swedish armies broke into more flexible, smaller regiments. These units smashed the tercios with combined arms tactics that also employed field artillery and a return to cavalry shock.

arquebus.

Also “arkibuza,” “hackbutt,” “hakenbüsche,” “harquebus.” Any of several types of early, slow-firing, small caliber firearms ignited by a matchlock and firing a half-ounce ball.

The arquebus was a major advance on the first “hand cannon” where a heated wire or handheld slow match was applied to a touch hole in the top of the breech of a metal tube, a design that made aiming by line of sight impossible.

That crude instrument was replaced by moving the touch hole to the side on the arquebus and using a firing lever, or serpentine, fitted to the stock that applied the match to an external priming pan alongside the breech.

This allowed aiming the gun, though aimed fire was not accurate or emphasized and most arquebuses were not even fitted with sights. Maximum accurate range varied from 50 to 90 meters, with the optimum range just 50-60 meters.

Like all early guns the arquebus was kept small caliber due to the expense of gunpowder and the danger of rupture or even explosion of the barrel. However, 15th-century arquebuses had long barrels (up to 40 inches). This reflected the move to corning of gunpowder.

The development of the arquebus as a complete personal firearm, “lock, stock, and barrel,” permitted recoil to be absorbed by the chest.

That quickly made all older handguns obsolete. Later, a shift to shoulder firing allowed larger arquebuses with greater recoil to be deployed. This also improved aim by permitting sighting down the barrel. The arquebus slowly replaced the crossbow and the longbow during the 15th century, not least because it took less skill to use, which meant less expensive troops could be armed with arquebuses and deployed in field regiments.

This met with some resistance: one condottieri captain used to blind and cut the hands off captured arquebusiers; other military conservatives had arquebusiers shot upon capture. An intermediate role of arquebusiers was to accompany pike squares to ward off enemy cavalry armed with shorter-range wheel lock pistols.

Among notable battles involving arquebusiers were Cerignola (April 21, 1503), where Spanish arquebusiers arrayed behind a wooden palisade devastated the French, receiving credit from military historians as the first troops to win a battle with personal firearms; and Nagashino, where Nobunaga Oda’s 3,000 arquebusiers smashed a more traditional samurai army. The arquebus was eventually replaced by the more powerful and heavier musket.

Arquebus vs archery

In terms of accuracy, the arquebus was extremely inferior to any kind of bow. However, the arquebus had a faster rate of fire than the most powerful crossbow, had a shorter learning curve than a longbow, and was more powerful than either. An arquebusier could carry more ammunition and powder than a crossbowman or longbowman could with bolts or arrows.

The weapon also had the added advantage of scaring enemies (and spooking horses) with the noise. Perhaps most importantly, producing an effective arquebusier required a lot less training than producing an effective bowman. During a siege it was also easier to fire an arquebus out of loopholes than it was a bow and arrow.