Category: Well I thought it was neat!

By LAWRENCE J. SISKIND

The lives of Theodore Roosevelt and Winston Churchill overlapped, but they met in person only once — at a dinner in the Governor’s Mansion in Albany, New York on December 10, 1900. The 42-year old Roosevelt was about to relocate to Washington DC to assume his duties as Vice President. The 26-year old Churchill, who was visiting America to shore up his finances by a lecture tour, was about to take his seat in Parliament.

What happened at their dinner is unknown. But to the extent historians have noticed the dinner (which isn’t a large extent[i]), they have accepted the view, first attributed to Roosevelt’s daughter Alice, that the two men did not get along because they were so much alike.[ii] As Robert Pilpel, in his Churchill in America 1895 – 1961, put it: “It was a case of likes repelling.”[iii]

But was it?

We will never know for certain because the witnesses are not available for deposition. But based on the evidence, the “likes repelling” theory is unpersuasive. Something else, something deeper, was afoot.

Let’s review the record, starting with Winston Churchill’s reaction to the dinner.

His reaction was a case of the dog not barking. If one examines Churchill’s papers, one might conclude that the event never took place. On December 21, 1900, eleven days after the dinner, he wrote a detailed letter to his mother, describing his American trip. The letter mentions his lectures, his earnings, and his many meetings with American luminaries. It mentions that he was “considerably impressed” by President McKinley. But as to Theodore Roosevelt, Churchill says nothing.[iv]

Subsequently, Churchill’s references to Roosevelt are very few and entirely benign. In December 1906, after an earthquake had destroyed Kingston, Jamaica, an American admiral landed armed soldiers to help clear the rubble.

Sir Alexander Swettenham, Governor of the island, issued a harsh letter condemning the move, and pointing out that the recent looting of a New York millionaire’s house would not have justified a British admiral landing armed soldiers to help the police. President Roosevelt complained to London about the ill-tempered letter, and Churchill, then the top assistant to the Colonial Secretary, supported Roosevelt, calling Swettenham “an ass … wrong on every point.”[v]

In December 1908, upon learning that the lame duck President was planning an African safari, Churchill sent Whitelaw Reid, the American ambassador in London, a copy of My African Journey, his account of his own 1907 hunting exploits on that continent, with a request to forward it on to Roosevelt.[vi]

In April 1918, Churchill suggested enlisting Roosevelt as a plenipotentiary in a rather far-fetched and never implemented mission to persuade the Bolsheviks to bring Russia back into the war on the side of the Allies.[vii]

That is all there is regarding the impression Roosevelt made on Churchill. There is nothing to show that Churchill was repelled by Roosevelt.

When we investigate Churchill’s impression on Roosevelt, a very different picture emerges.

To start, Roosevelt’s papers show that the dinner was actually his idea. Roosevelt was eager to meet the young Englishman in person. On December 4, 1900, Major James Burton Pond, the manager of Churchill’s American lecture tour, had invited then Governor Roosevelt to attend Churchill’s upcoming New York City lecture and had even offered him a box in the theater. Pond’s transparent aim in inviting Roosevelt was to use his famous name to promote the Churchill event.

Roosevelt reasonably might have ignored the invitation, or dismissed it with a curt letter of regret. Instead, in his December 6 response, he first declined the invitation due to a scheduling conflict, then lobbied for a meeting:

I am really sorry as I am a great admirer of Mr. Churchill’s books, and should very much like to have a chance of meeting him socially. Is he now in New York? I should greatly like to have him take lunch or dinner with me if he is in Albany on Monday; or lunch if he is here Tuesday, of next week. Where shall I write him?[viii]

Major Pond had merely invited Roosevelt to attend a lecture. He had not suggested a personal meeting. But here was Roosevelt inviting Churchill to break bread with him in Albany, and offering no fewer than three possible time slots, each one a meal rather than a perfunctory meet-and-greet office session. Roosevelt’s inquiry as to where he could write Churchill directly reveals his eagerness for a personal meeting.

But while Roosevelt very much wanted “a chance of meeting [Churchill] socially,” once he had that chance, he didn’t like what he saw.

After the dinner, on July 12, 1901, the now Vice President Roosevelt wrote to Hermann Speck von Sternburg, a family friend and German diplomat, who had spent time in India. The letter dealt mainly with military and international affairs. Roosevelt wrote: “I saw the Englishman, Winston Churchill here, and although he is not an attractive fellow, I was interested in some of the things he said.” [ix]

The “things” that interested Roosevelt were Churchill’s views on the fighting qualities of Gurka, Sikh, Punjabi, and Pathan regiments. The casual reference to Churchill’s unattractiveness was purely gratuitous and had nothing to do with the subject of the letter. But it set a tone. In subsequent letters, Roosevelt would miss no opportunity to denigrate Churchill, whether relevant to the correspondence or not.

On September 12, 1906, the now President Roosevelt wrote to Henry Cabot Lodge. Referencing Churchill’s recently published 2-volume biography of his father, Roosevelt commented: “I dislike the father and dislike the son, so I may be prejudiced.” He proceeded to describe both Churchills as “possess[ing] such levity, lack of sobriety, lack of permanent principle, and inordinate thirst for that cheap form of admiration which is given to notoriety, as to make them poor public servants.”[x] (Lodge responded a few days later, admitting he had not read the biography, but adding that he considered the son “clever but conceited to a degree which it is hard to express either in words or figures.”[xi])

On October 25, 1906, Roosevelt wrote to John St. Loe Strachey, a British journalist and newspaper proprietor. Strachey had asked Roosevelt for his opinion of William Randolph Hearst. Roosevelt replied: “[I]t is a little difficult for me to give you an exact historic judgment about a man whom I so thoroly [sic] dislike and despise as I do Hearst.” He called Hearst “a man without any real principle.” Then, reverting to his favored object of invective, Roosevelt added: “But when I have said this, after all, I am not at all sure that I am saying much more of Hearst than could probably be said … about both Winston Churchill and his father, Lord Randolph.”[xii] Although the subject was Hearst, Roosevelt could not resist bringing up Churchill.

For Roosevelt, it wasn’t enough to express his distaste for Churchill himself. He also expressed his distaste for those who admired Churchill. On November 14, 1906, Roosevelt wrote to Lodge again, this time attacking Archibald Primrose, the fifth Earl of Rosebery. The former Prime Minister’s sin was praising Winston Churchill’s biography of his father as “remarkable.” Roosevelt indignantly referenced Rosebery’s “lack of sense or proportion.”[xiii]

On May 23, 1908, Roosevelt wrote to his son Theodore Jr., then a student at Harvard. Young Theodore had just read Churchill’s biography of Lord Randolph and wanted to know his father’s opinion. Roosevelt answered: “Yes, that is an interesting book of Winston Churchill’s about his father, but I can’t help feeling about both of them that the older one was a rather cheap character, and the younger one is a rather cheap character.” (Underlining in original.)[xiv]

On November 6, 1908, the lame duck President Roosevelt wrote to British historian George Otto Trevelyan about the recent election of his then friend (and later opponent) William Howard Taft to succeed him. After discussing his post-White House plans, Roosevelt turned to history and once again attacked Rosebery, this time for the way “he speaks of Winston Churchill’s clever, forceful, rather cheap and vulgar life of that clever, forceful, rather cheap and vulgar egoist, his father.”[xv]

In January 1909, when Roosevelt received Churchill’s gift of his African Journey, he was taken aback. He admired the account but he didn’t like the author. So he dashed off a short thank you note to the donor (in which he expressed the hope that he “shall have as good luck as you had”),[xvi] and forwarded it to Ambassador Reid, with this cover: “I do not like Winston Churchill but I suppose I ought to write him. Will you send him the enclosed letter if it is all right?”[xvii]

Time did not moderate Roosevelt’s hostility.

September 10, 1909 found the former President at the foot of Mount Kenya, during the hunt in which he hoped to match Churchill’s luck. In a letter to Lodge and his wife, handwritten in pencil, Roosevelt described the American influence on British colonial reading habits. “Among the novels I see in the houses no English ones are more common than for instance, David Harum, or Winston Churchill’s – I mean, of course our Winston Churchill, Winston Churchill the gentleman.”[xviii] Roosevelt’s reference to “Winston Churchill the gentleman” was to the popular New Hampshire novelist, whose books were widely read and whose political career Roosevelt supported. The implication that the English Winston Churchill was not a gentleman is consistent with Roosevelt’s earlier references to Churchill as “unattractive” and “cheap.”

Following his African tour, Roosevelt traveled to Europe, where he met with a long parade of prominent royal, political, and intellectual figures. But the parade was not long enough to include Winston Churchill, who had been appointed Home Secretary in February 1910. On June 4, Roosevelt wrote to Lodge: “I have had a most amusing and interesting time here, but, literally there hasn’t been a five minutes free…. I have refused to meet Winston Churchill, being able to avoid causing any scandal by doing so.”[xix]

On October 1, 1911, Roosevelt reminisced about his African adventure in a long letter to Trevelyan. Discussing his visit to Khartoum, he described how the white settlers in British East Africa hoped that he would speak sympathetically about them when he traveled on to England. Then he added: “They had hoped much from Winston Churchill’s visit, but for various reasons most of them had disliked him ….”[xx] This of course was Roosevelt projecting his own enmity toward Churchill onto the local English community.

On October 5, 1911, in a letter to the playwright David Gray, Roosevelt described his experience as a special ambassador to the funeral of King Edward the previous year. “I dislike Winston Churchill and would not meet him,” he recounted, “but I was anxious to meet both Lloyd George and John Burns, and I took a real fancy to both of them.”[xxi]

On August 22, 1914, shortly after hostilities had erupted, Roosevelt wrote to Arthur Hamilton Lee, the British politician and soldier. Just as when he received Churchill’s African Journey, Roosevelt was in a bind. It was painful for Roosevelt to say anything positive about Churchill but the situation called for doing so.

Churchill, then First Lord of the Admiralty, had had the foresight to mobilize the fleet before war broke out, much as Roosevelt himself had ordered Admiral Dewey to prepare to attack the Spanish Fleet on the eve of the Spanish-American War. Roosevelt, perhaps gritting his teeth, wrote: “I have never liked Winston Churchill, but in view of what you tell me as to his admirable conduct and nerve in mobilizing the fleet, I do wish that if it comes in your way you would extend to him my congratulations on his action.” To assure that his rare compliment did not gain publicity, he added: “It must be strictly confidential, of course.”[xxii]

The evidence, taken as a whole, contradicts the verdict of Alice Roosevelt and some historians that this was a case of “likes repelling.”

First, the “repelling” was completely one-sided. Theodore Roosevelt was thoroughly repelled by Winston Churchill. After the dinner, he seems to have been determined to make sure that everyone knew how much he disliked Churchill. But nothing suggests that Winston Churchill was repelled by Roosevelt. After the dinner, Churchill simply didn’t think about Roosevelt very much, and when he did think about him, he seems to have just assumed that all was well between them.[xxiii]

Second, Roosevelt and Churchill were hardly “likes.” Granted both were sportsmen born into upper class families, and both pursued political careers. But they were markedly different in age, experience, and family ties. Roosevelt grew up in a warm, loving home, raised by parents who adored him. Churchill was largely ignored by his parents; any warmth he received growing up came from his nanny, Mrs. Everest. Roosevelt favored athletic endeavors that involved close physical contact, such as boxing and wrestling. Churchill stayed a polo mallet’s length away from his competitors.

If this were not a case of “likes repelling,” then what accounts for Roosevelt’s hostility?

As his correspondence with Major Pond shows, Roosevelt was anxious to meet Churchill. When the 26-year old Churchill showed up for dinner, Roosevelt doubtless expected a certain degree of deference from the younger man.

For all his progressive political inclinations. Roosevelt was deeply conservative in his views on social propriety and decorum. If one were a gentleman, one behaved in a certain way. Roosevelt rode, worked, and endured hardships as well as the lowliest ranch hand in the Badlands of the Dakota Territory.

But it was understood that when he slept in his cabin, the ranch hands were to move their mattresses up to the loft because the “boss” had to have the downstairs to himself. Similarly, the neighboring ranchers were expected to address him as “Mr. Roosevelt,” even if they were wealthy enough to consider themselves his equal. Nobody called him “Roosevelt” and certainly no one called him “Teddy.”[xxiv]

But the brash young visitor had no time for such niceties. If Roosevelt was ruled by his views of social etiquette, Churchill was constrained by his views of his mortality. He believed he had only a short time to live. His father had died at the age 45. His father’s sisters died at the ages of 45 and 51, and their brother died at 48. Churchill did not expect to live much beyond the 42 years of his dinner host.[xxv]

Churchill was not inclined to defer to Roosevelt’s seniority because he did not expect to live long enough to enjoy such seniority of his own.

So one diner appeared that evening expecting deference, and the other diner arrived demanding equality. We can imagine a dinner conversation marred by the incongruity. Roosevelt is accustomed to dominating the conversation. But young Churchill believes he has just as much wisdom to impart, and refuses to yield the floor. Roosevelt wants to talk about his charge up the San Juan Heights. Churchill tries to cut him short so that he can orate on Omdurman. They both consider themselves experts on Indian affairs – although they have in mind Indians of different continents.

For Churchill, the evening’s give-and-take must have been great fun. He probably drank and talked a good deal, as was his wont. More likely than not, he left Albany happy with his performance, and confident that his merry self-assurance had made a positive impression on his older and more accomplished host. In the future, he would just assume that Roosevelt would welcome the chance to read his book on hunting. Why wouldn’t he? After all, they had had such a good time that night at dinner!

But for Roosevelt, the evening must have been one long infuriating ordeal. The brash younger Englishman did not behave as he was supposed to. Rather than conducting himself like a gentleman, he behaved like a showman. He spoke when he should have listened. He interrupted when he should have deferred. How cheap! How conceited! How insufferable! He was not an attractive dinner guest and would never be welcome at his table again.

And so the two giants of history met for dinner and parted ways, each left with a different aftertaste.

Lawrence J. Siskind is of counsel at Coblenz Patch Duffy & Bass LLP in San Francisco, where he specializes in intellectual property law.

[i] Andrew Roberts, in Churchill: Walking with Destiny, devotes three sentences to the event and its aftermath. (p. 78) William Manchester gives it one half of one sentence in his Churchill biography The Last Lion. (p. 331) The dinner does not even merit a mention in Edmund Morris’s The Rise of Theodore Roosevelt.

[ii] Richard Langworth, Churchill and Theodore Roosevelt, Finest Hour 163, Summer 2015 (February 8, 2015).

[iii] Robert H. Pilpel, Churchill in America 1895 – 1961, p. 38.

[iv] The Churchill Archives, December 21, 1900 Letter from Winston Churchill to Jennie Churchill, CHAR 28/26/77-79.

[v] Richard Langworth, op. cit.

[vi] The Churchill Archives, December 8, 1908 Letter from Whitelaw Reid to Winston Churchill, CHAR 2/36/33.

[vii] Richard Langworth, op.cit.

[viii] The Letters of Theodore Roosevelt, Vol. II, The Years of Preparation 1898 – 1900, p. 1454.

[ix] The Letters of Theodore Roosevelt, Vol. III, The Square Deal 1901 – 1903, pp. 116 – 117.

[x] Selections from the Correspondence of Theodore Roosevelt and Henry Cabot Lodge 1884 – 1918, Vol. II, pp. 231 -232.

[xi] Id., at 232.

[xii] The Letters of Theodore Roosevelt, Vol. V, The Big Stick 1905 – 1907, p. 468.

[xiii] Selections from the Correspondence of Theodore Roosevelt and Henry Cabot Lodge 1884 – 1918, Vol. II, pp. 260 -261.

[xiv] The Letters of Theodore Roosevelt, Vol. VI, The Big Stick 1905 – 1907, p. 1034. A carbon copy of the letter is in the Theodore Roosevelt Collection in the Library of Congress in Washington DC. The staff kindly made the carbon copy available to the author. It shows the underlining.

[xv] Id., at p. 1329.

[xvi] The Letters of Theodore Roosevelt, Vol. VI, The Big Stick 1905 – 1907, p. 1467.

[xvii] Id., at p. 1465.

[xviii] Selections from the Correspondence of Theodore Roosevelt and Henry Cabot Lodge 1884 – 1918, Vol. II, p. 349.

[xix] The Letters of Theodore Roosevelt, Vol. VII, The Days of Armageddon 1909 – 1914, p. 87.

[xx] Id., at p. 350.

[xxi] Id., at p. 406.

[xxii] Id., at p. 810.

[xxiii] Churchill had a habit of forgetting people, and two of them were Roosevelts. On July 29, 1918, during World War I, Churchill met the Assistant Secretary of the US Navy, Franklin Roosevelt, at a dinner in London. Twenty-three years later, on August 9, 1941, during World War II, the two men met again in Placentia Bay near the shore of Newfoundland. Franklin Roosevelt noted that the two had met before during the Great War, and referred to it as one of his “treasured recollections.” Churchill admitted that the event “had slipped his memory.” Andrew Roberts, Churchill: Walking With Destiny, p. 673.Fortunately for the cause of Allied cooperation, this particular President Roosevelt was not as easily offended as the earlier one.

[xxiv] Edmund Morris, The Rise of Theodore Roosevelt, p. 331.

[xxv] Andrew Roberts, Churchill: Walking With Destiny, p. 31.

Politicians refer to themselves as public servants. Swamp creatures like Joe Biden will extol their many decades of employment in Washington DC as though they had been some kind of galley slave toiling away on an Athenian man o’ war. I have actually met a couple of those guys. Their idea of selfless service does not quite match my own.

American legislators spend money like drunken sailors. Actually, that’s not true. Drunken sailors couldn’t even begin to burn cash in as profligate a manner as might your typical freshman congressman. They’ve raised wasting money to an art form.

You think I’m kidding. Back when I was a soldier I spent a week as a local liaison officer for a group of congressmen on a fact-finding mission after the First Gulf War. It was amazing just watching them eat. They’d go to the nicest restaurant in town and order one of anything they might be curious about. Then they swapped plates around so everybody got a taste. One of my several duties was to scurry back and forth to the Officers’ Club cashing $500 government traveler’s checks to pay for it all. It was surreal.

Everybody in DC has sold their soul to somebody. I’ll champion the folks on my side of the aisle in the vain hope that they might someday just leave me the heck alone, but they are all irredeemably corrupt. The system perpetuates itself. It will never get better.

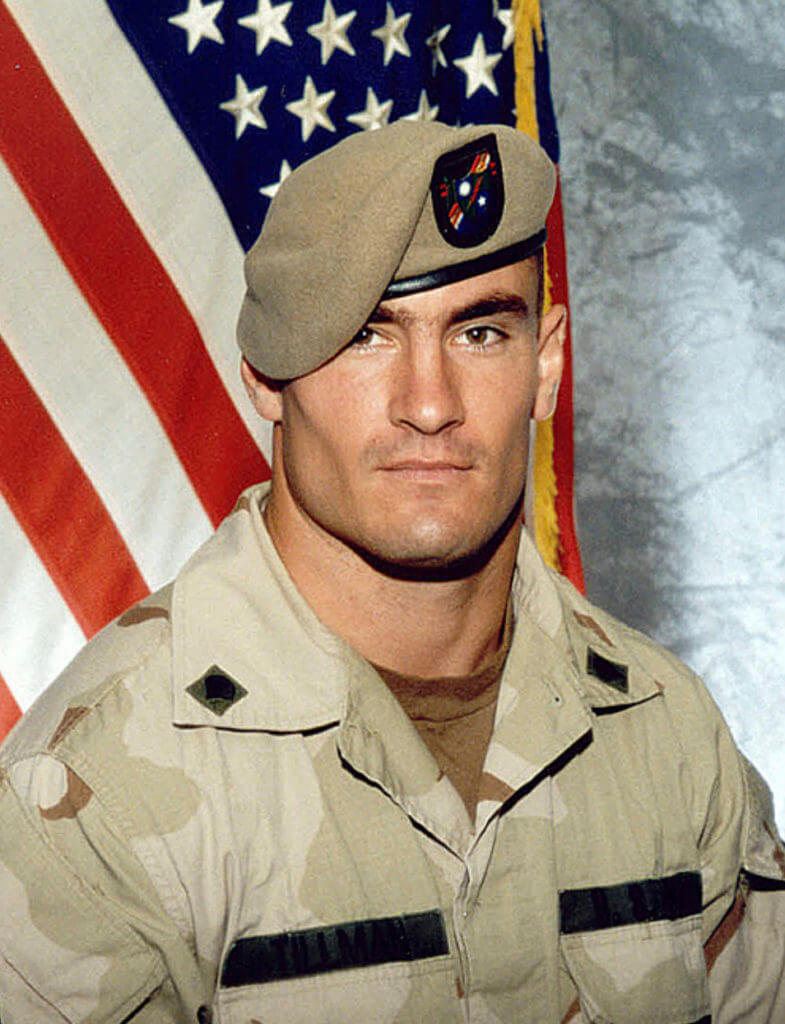

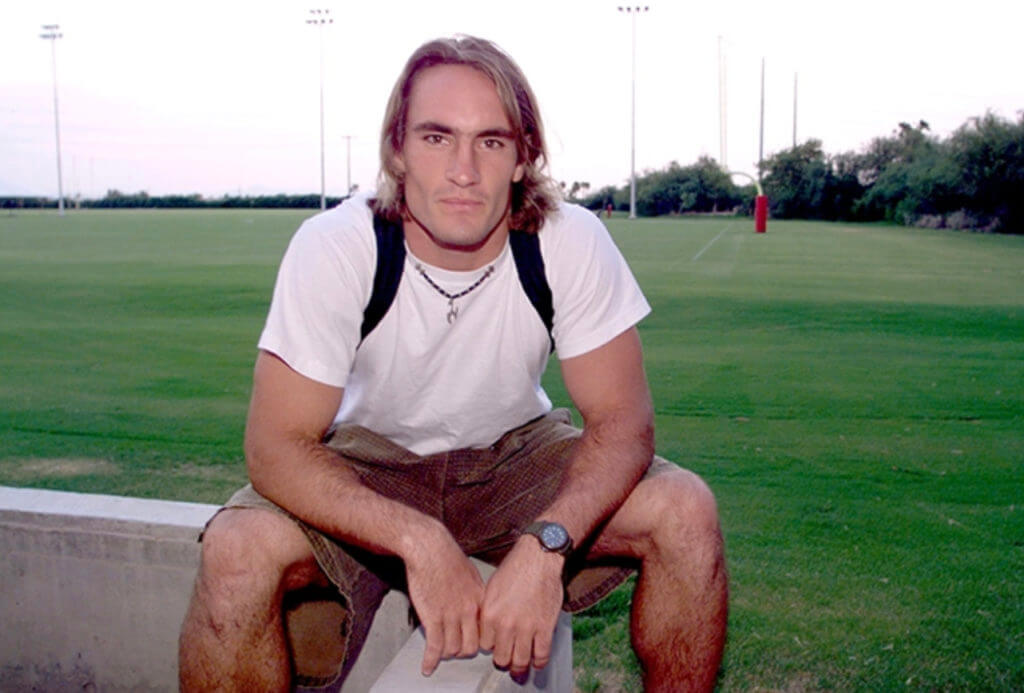

On May 31, 2002, Pat Tillman and his brother Kevin walked into a local recruiting office and enlisted in the US Army. Pat walked away from a $3.6 million professional football contract and Lord knows what else so he could serve his country in the immediate aftermath of 911. Pat Tillman’s story is that of a conflicted man and a horribly flawed system. However, his is a tale of epic sacrifice and genuine selfless service.

Origin Story

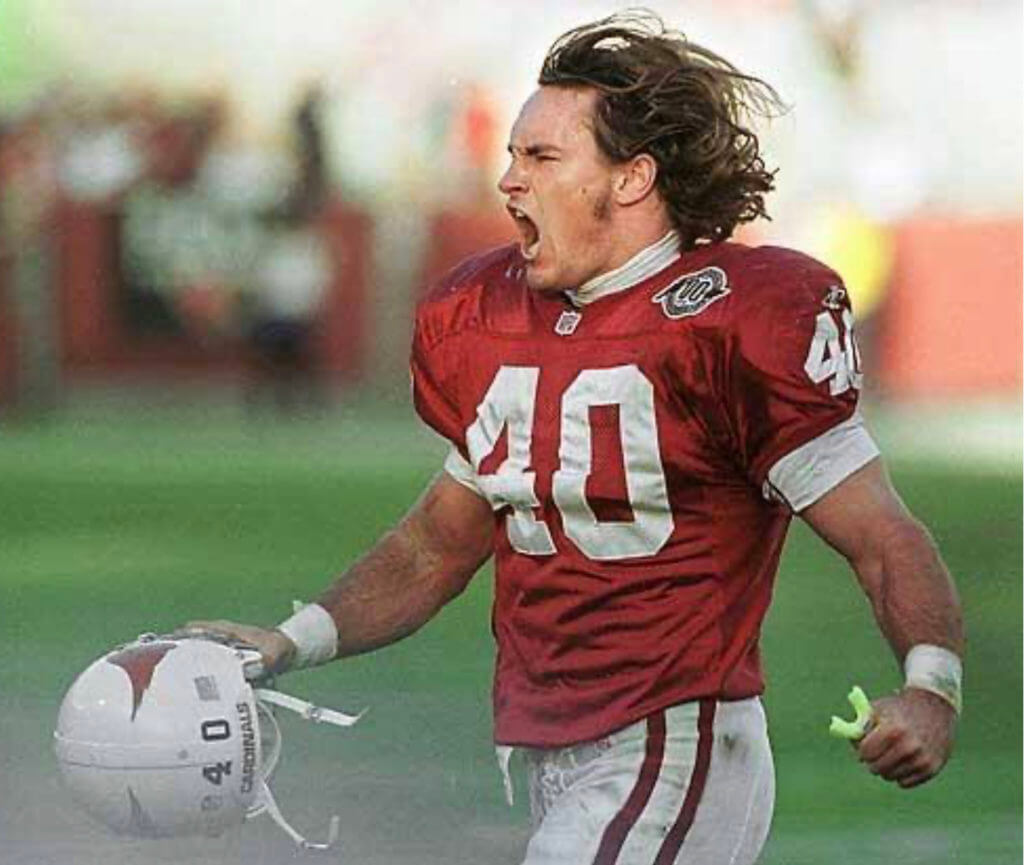

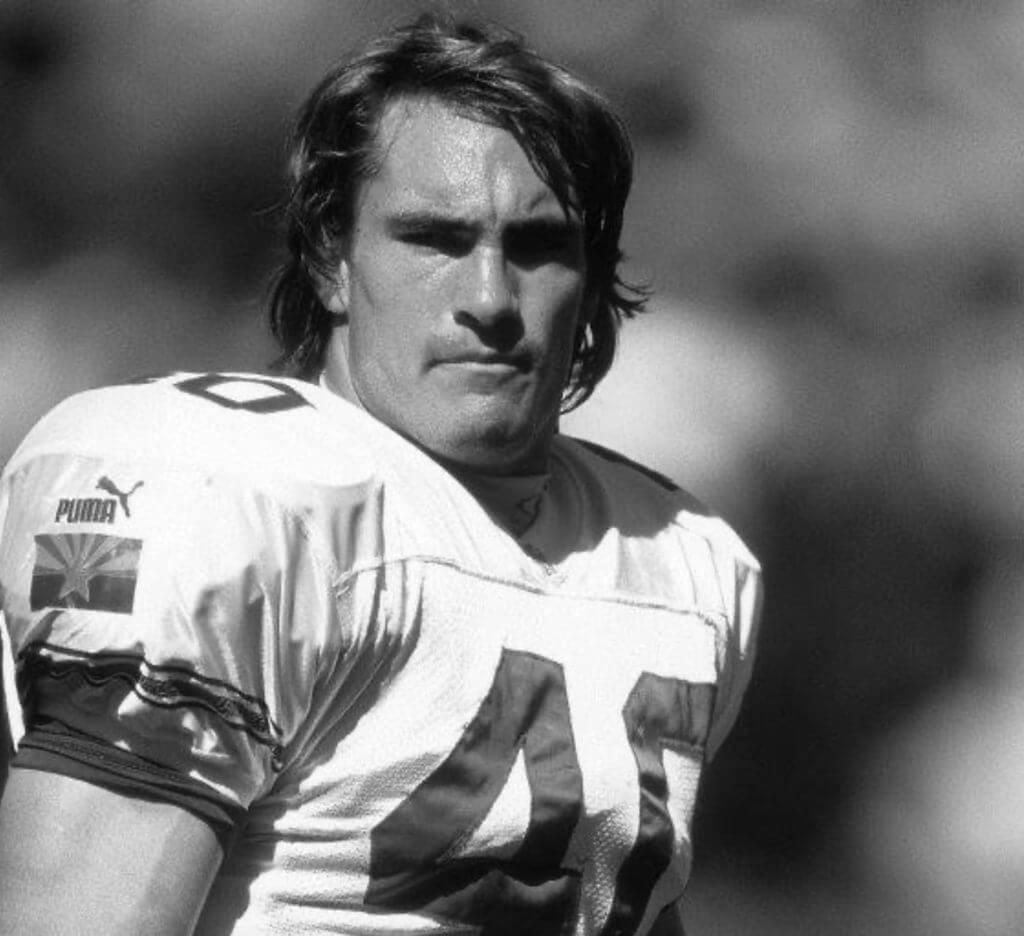

Pat Tillman was the eldest of three sons born to Patrick and Mary Tillman in Fremont, California. By NFL standards, Tillman was not a terribly big man. He stood 5’11” and weighed 202 pounds when dressed out as a safety for the Arizona Cardinals. Pat personified the axiom, “It’s not the size of the dog in the fight, it’s the size of the fight in the dog.”

In high school Tillman preferred baseball, but he failed to make the team as a freshman. At that point, he turned his attention to the gridiron. Throughout his childhood and adolescence, Pat was powerfully close to his friends and family. He married his childhood sweetheart just before he enlisted in the Army. He and his brother Kevin enlisted together, trained together, and were eventually both assigned to the 2d Ranger Battalion based at Fort Lewis, Washington.

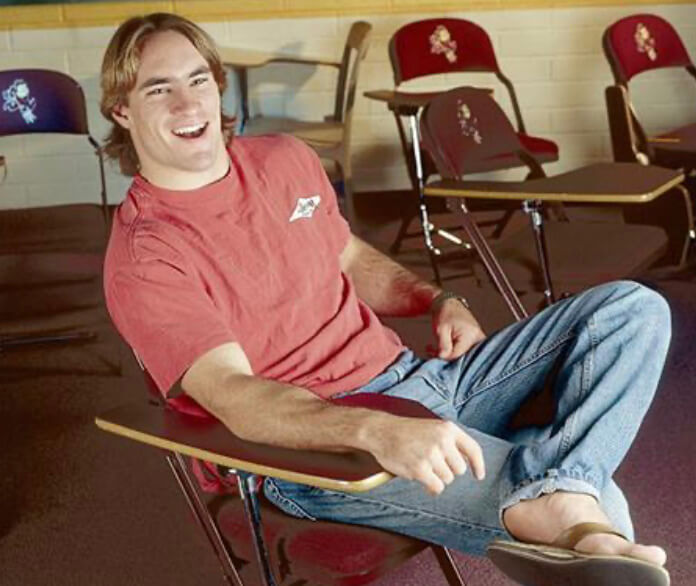

Pat Tillman attended Arizona State University on a football scholarship and excelled as a linebacker. An exceptionally deep young man, Tillman was well read and made good grades. He maintained a 3.85 GPA in marketing and graduated in 3.5 years despite the rigors of starting on his college football team.

Pat thrived in the NFL. Sports Illustrated writer Paul Zimmerman named Tillman to the 2000 NFL All-Pro team based upon his stellar performance as a defensive player. He turned down a $9 million offer to move to the St. Louis Rams out of loyalty to his Arizona team.

Eight months after the 911 attacks and with the remainder of his 15 games completed from his 2001 contract, Pat Tillman left $3.6 million on the table to go to Army basic training alongside his brother. Pat’s brother Kevin gave up a burgeoning career in minor league baseball for the same path. These two men put their love of country ahead of the sorts of things the rest of us would just about kill for.

Appreciate the details here. I’m a happily married hetero man, and even I admit that Pat Tillman was an exceptionally good-looking guy. Intelligent, articulate, and well-educated, Tillman had the world by the tail. Once his time in the NFL was complete Pat Tillman could have easily parlayed his gifts and experiences into a career on television or in Hollywood. Instead, he opted for the Ranger Regiment.

I was an Army aviator, but I worked with those guys on occasion. Theirs was an absolutely miserable life. Junior enlisted soldiers don’t get paid beans, and the optempo in the Ranger Battalions is utterly grueling. In less than two years on active duty, Pat Tillman completed basic training and AIT as well as the Ranger Assessment and Selection Program. He was deployed to Iraq as part of Operation Iraqi Freedom in September of 2003 after which he attended Ranger School at Fort Benning. Once a fully tabbed Ranger, he returned to Second Bat at Lewis and deployed to Afghanistan where he was based at FOB Salerno.

Up until this point, Pat Tillman was the US Army’s poster child. An American superhero with a face right out of central casting, Tillman’s story could not have been any more compelling had it been drafted by an action novelist. Then Something Truly Horrible happened.

The Incident

Combat is an ugly, filthy, chaotic thing. It is seldom as tidy or predictable as the movies and sand table exercises depict it to be. On April 22, 2004, the fog of war claimed a genuine American hero.

On a forgotten road leading from the Afghan village of Sperah about 40 klicks outside of Khost, Pat Tillman’s small HUMVEE-mounted patrol ran into trouble. Their mission that day was to retrieve a disabled HUMVEE. This tale is made all the more tragic in that we abandoned tens of thousands of these vehicles when we fled Afghanistan recently. The details are fiercely debated to this day, but here is the official description.

Tillman was in the lead vehicle designated Serial 1. Serial 1 passed through a mountainous pass and was roughly one kilometer ahead of Serial 2, the following HUMVEE. At that point, Serial 2 was purportedly engaged by hostile forces.

Upon hearing of the ambush, the Rangers in Serial 1 dismounted and made their way on foot back toward an overwatch position where they could provide supporting fires for Serial 2. In the resulting chaos, the Rangers of Serial 2 lost touch with the specific location of the lead Rangers. In the violent exchange of fire that followed Tillman’s Platoon Leader and his RTO (Radio Telephone Operator) were wounded. An allied member of the Afghan Militia Force was killed. Pat Tillman caught three 5.56mm rounds from an M249 SAW to the face from a range of 10 meters and died instantly.

The Weapon

First introduced in 1984, the Belgian-designed M249 Squad Automatic Weapon was an Americanized version of the FN Minimi. An open-bolt, gas-operated design, the M249 was conceived to provide the Infantry squad with a portable source of high-volume, belt-fed automatic fire. The M249 has seen action in every major military engagement since the US invasion of Panama in 1989.

The M249 weighs 17 pounds empty and 22 pounds with a basic load of 200 linked rounds. The weapon fires from an open bolt and features a quick-change barrel system. The gun will feed on either disintegrating linked belts or standard STANAG M4 magazines. In my experience, the magazine feed system was never terribly reliable.

USSOCOM adopted a lighter, more streamlined version of the M249 titled the Mk46 for use with special operations forces. The M4 magazine well, vehicle mounting lugs, and barrel change handle were all removed on the Mk 46 to save weight. The USMC has aggressively supplemented their rifle squads with the HK M27 Infantry Automatic Rifle in lieu of many of their SAWs. These weapons are currently issued at a ratio of 27 IARs and 6 SAWs per rifle company. The Next Generation Squad Weapon-Automatic Rifle program is tasked with finding a suitable replacement for the aging M249’s in the Army inventory.

The Rest of the Story

What happened next was a blight on the US Army. To have Pat Tillman, the real live Captain America killed due to friendly fire in a botched combat operation was not the story the Army wanted pushed. As a result, several senior Army officers moved to massage the narrative and outright suppress the story to both the media and the Tillman family. The end result was an absolutely ghastly mess.

There were allegations that Tillman, by now disillusioned with the war in Iraq, was about to offer an interview with controversial activist Noam Chomsky upon his return from his Afghanistan deployment that would be critical of the Bush Administration.

As Tillman’s death occurred in a crucial time leading up to the 2004 Presidential elections conspiracy theorists even proposed that he had been intentionally murdered. However, interviews with his fellow Rangers verified that Tillman was a popular and selfless member of the team. In the final analysis, it all seems to have been a truly horrible mistake. After several investigations undertaken by the military, three mid-level Army leaders purportedly received administrative punishment as a result.

A word on the conspiracies. Soldiers don’t fight for mom, apple pie, and America. They fight for each other. There’s just no way you could get a Ranger to intentionally shoot another Ranger to protect the reputation of a sitting President. This was simply a horrible accident.

The sordid circumstances surrounding the death of Pat Tillman in no way diminish the truly breathtaking scope of the man’s patriotism and sacrifice. Tillman was an avowed atheist throughout his life. After his funeral, his youngest brother Richard asserted, “Just make no mistake, he’d want me to say this: He’s not with God, he’s f&%ing dead, he’s not religious.” Richard added, “Thanks for your thoughts, but he’s f&%in’ dead.” It was an undeniably strange end for a genuine American hero.

Soldiers in combat will often pen a “just in case” letter to be opened in the event of their death. Pat’s note to his wife Marie said, “Through the years I’ve asked a great deal of you, therefore it should surprise you little that I have another favor to ask. I ask that you live.”

And live she did. Marie Tillman today is Chairman and Co-Founder of The Pat Tillman Foundation. This non-profit works to “unite and empower remarkable military service members, veterans, and spouses as the next generation of public and private sector leaders committed to service beyond self.” The Foundation has sponsored 635 Tillman Scholars and invested some $18 million in philanthropy. Marie has since remarried and is the mother of five children.

The below is an excerpt from the 1978 book, Olympic Shooting, written by Col. Jim Crossman and published by the NRA.

The National Skeet Shooting Association

By Colonel Jim Crossman

Unlike most shooting events, skeet is of fairly recent origin and it is easily possible to trace the history of this shotgun game and its parent organization, the National Skeet Shooting Association.

Unable to get in enough grouse hunting to satisfy themselves, and not enthusiastic about trapshooting because it did not simulate bird shooting conditions, a group of New England hunters experimented with traps and clay birds until they worked out a game that seemed practical as field training, was fun to shoot, and was not too difficult to set up.

One of the group, W. H. Foster, became associated with a publishing firm which put out two very popular outdoor magazines, the five-cent Hunting and Fishing and the expensive 10-cent National Sportsman. Foster’s articles on the subject of the new game, first called “clock shooting,” aroused so much interest among readers that it was promoted as a new shooting sport. In 1925 complete rules and instructions were published. At the same time a prize was offered for the best name. “Skeet” was the name selected, and a good name it was, so that it remains skeet to this day.

Skeet grew rapidly up to World War II. The designers of skeet had done their work well in working up a game for teaching people to hit moving targets. So, skeet went to war. With the sudden urgent necessity of training aerial gunners as well as anti-aircraft gunners how to hit a moving airplane, skeet was seized upon as an important step in teaching swing and lead on a flying target. Many skeet shooters of the time found themselves in uniform, teaching skeet every day. Thousands of young men were exposed to shotgun shooting for the first time during this training, which was partly responsible for the great increase in shooting and hunting after the war.

The Hunting and Fishing and National Sportsman magazines had a proprietary interest in skeet, since they had originally promoted it and had devoted much money and magazine space to it. Thus, while there was a National Skeet Shooting Association in the 1930s, its officers read like the masthead of the magazines. But with the war and the lack of ammunition, skeet shooting for civilians practically stopped. The two magazines went out of business and the association became inactive.

With the end of the war, the National Rifle Association of America undertook to revive the skeet association. The NRA lent the embryo organization money and provided it office space. E. F. “Tod” Sloan was appointed manager of the organization. Sloan, although a rifle shooter, had long experience in competitive shooting and in promoting civilian shooting, his most recent military assignment having been as the Army’s Director of Civilian Marksmanship.

In 1952, after the organization was on its feet, Sloan resigned and the NRA bowed out, with Sloan taking a position as NRA field representative in the West, a position he filled with distinction. The skeet organization was turned over to the members and their elected officials. For many years, NSSA conducted its championships at various locations across the country, including the International Gun Club at San Antonio, Texas. This was a privately owned beautiful big layout, with all sorts of shotgun shooting taking place and with much room for expansion. The NRA conducted tryouts for its shotgun squads for the 1967 World Moving Target Championships and the 1968 Olympics at this club. In recent years the club ran into financial difficulties and NSSA bought it in 1974 and has moved its headquarters to that location.

Skeet is relatively new to the Olympic Games, although it has been part of the UIT program for many years. Skeet first appeared in the Olympic program in 1968 and it carried on into 1972 and 1976, although in a form barely recognizable by American shooters.

U.S. skeet has gotten away from some of the basic principles of the original game and a few major changes in rules have made it a much easier game. International skeet, on the other hand, is more difficult than the original sport, so there is now considerable difference between skeet as shot in the United States and as shot in international competition. There has been much discussion about making U.S. skeet tougher, both to reduce the large number of perfect tie scores and to improve international chances, but a vote by the directors in 1968 said no to the attempt to make U.S. skeet more difficult.

For those shooters who are interested in international skeet, the NSSA has established a separate International Division and there are a few events at the national championship shot under the international rules. The NSSA, not a member of the UIT, now works closely with the National Rifle Association in promoting international skeet. [Note: USA Shooting took the reins for international and Olympic skeet development and competition in the United States in 1994.]

Americanism

Four centuries and a quarter have gone by since Columbus by discovering America opened the greatest era in world history. Four centuries have passed since the Spaniards began that colonization on the main land which has resulted in the growth of the nations of Latin-America. Three centuries have passed since, with the settlements on the coasts of Virginia and Massachusetts, the real history of what is now the United States began. All this we ultimately owe to the action of an Italian seaman in the service of a Spanish King and a Spanish Queen. It is eminently fitting that one of the largest and most influential social organizations of this great Republic,—a Republic in which the tongue is English, and the blood derived from many sources should, in its name commemorate the great Italian. It is eminently fitting to make an address on Americanism before this society.

DEMOCRATIC PRINCIPLES.

We of the United States need above all things to remember that, while we are by blood and culture kin to each of the nations of Europe, we are also separate from each of them. We are a new and distinct nationality. We are developing our own distinctive culture and civilization, and the worth of this civilization will largely depend upon our determination to keep it distinctively our own. Our sons and daughters should be educated here and not abroad. We should freely take from every other nation[2] whatever we can make of use, but we should adopt and develop to our own peculiar needs what we thus take, and never be content merely to copy.

Our nation was founded to perpetuate democratic principles. These principles are that each man is to be treated on his worth as a man without regard to the land from which his forefathers came and without regard to the creed which he professes. If the United States proves false to these principles of civil and religious liberty, it will have inflicted the greatest blow on the system of free popular government that has ever been inflicted. Here we have had a virgin continent on which to try the experiment of making out of divers race stocks a new nation and of treating all the citizens of that nation in such a fashion as to preserve them equality of opportunity in industrial, civil and political life. Our duty is to secure each man against any injustice by his fellows.

RELIGIOUS FREEDOM.

One of the most important things to secure for him is the right to hold and to express the religious views that best meet his own soul needs. Any political movement directed against any body of our fellow citizens because of their religious creed is a grave offense against American principles and American institutions. It is a wicked thing either to support or to oppose a man because of the creed he professes. This applies to Jew and Gentile, to Catholic and Protestant, and to the man who would be regarded as unorthodox by all of them alike. Political movements directed against men because of their religious belief, and intended to prevent men of that creed from[3] holding office, have never accomplished anything but harm. This was true in the days of the “Know-Nothing” and Native-American parties in the middle of the last century; and it is just as true today. Such a movement directly contravenes the spirit of the Constitution itself. Washington and his associates believed that it was essential to the existence of this Republic that there should never be any union of Church and State; and such union is partially accomplished wherever a given creed is aided by the State or when any public servant is elected or defeated because of his creed. The Constitution explicitly forbids the requiring of any religious test as a qualification for holding office. To impose such a test by popular vote is as bad as to impose it by law. To vote either for or against a man because of his creed is to impose upon him a religious test and is a clear violation of the spirit of the Constitution.

Moreover, it is well to remember that these movements never achieve the end they nominally have in view. They do nothing whatsoever except to increase among the men of the various churches the spirit of sectarian intolerance which is base and unlovely in any civilization but which is utterly revolting among a free people that profess the principles we profess. No such movement can ever permanently succeed here. All that it does is for a decade or so to greatly increase the spirit of theological animosity, both among the people to whom it appeals and among the people whom it assails. Furthermore, it has in the past invariably resulted, in so far as it was successful at all, in putting unworthy men into office; for there is nothing that a man[4] of loose principles and of evil practices in public life so desires as the chance to distract attention from his own shortcomings and misdeeds by exciting and inflaming theological and sectarian prejudice.

We must recognize that it is a cardinal sin against democracy to support a man for public office because he belongs to a given creed or to oppose him because he belongs to a given creed. It is just as evil as to draw the line between class and class, between occupation and occupation in political life. No man who tries to draw either line is a good American. True Americanism demands that we judge each man on his conduct, that we so judge him in private life and that we so judge him in public life. The line of cleavage drawn on principle and conduct in public affairs is never in any healthy community identical with the line of cleavage between creed and creed or between class and class. On the contrary, where the community life is healthy, these lines of cleavage almost always run nearly at right angles to one another. It is eminently necessary to all of us that we should have able and honest public officials in the nation, in the city, in the state. If we make a serious and resolute effort to get such officials of the right kind, men who shall not only be honest but shall be able and shall take the right view of public questions, we will find as a matter of fact that the men we thus choose will be drawn from the professors of every creed and from among men who do not adhere to any creed.

For thirty-five years I have been more or less actively engaged in public life, in the performance of my political duties, now in a public position, now in a private position.[5] I have fought with all the fervor I possessed for the various causes in which with all my heart I believed; and in every fight I thus made I have had with me and against me Catholics, Protestants and Jews. There have been times when I have had to make the fight for or against some man of each creed on grounds of plain public morality, unconnected with questions of public policy. There were other times when I have made such a fight for or against a given man, not on grounds of public morality, for he may have been morally a good man, but on account of his attitude on questions of public policy, of governmental principle. In both cases, I have always found myself fighting beside, and fighting against men of every creed. The one sure way to have secured the defeat of every good principle worth fighting for would have been to have permitted the fight to be changed into one along sectarian lines and inspired by the spirit of sectarian bitterness, either for the purpose of putting into public life or of keeping out of public life the believers in any given creed. Such conduct represents an assault upon Americanism. The man guilty of it is not a good American.

I hold that in this country there must be complete severance of Church and State; that public moneys shall not be used for the purpose of advancing any particular creed; and therefore that the public schools shall be non-sectarian. As a necessary corollary to this, not only the pupils but the members of the teaching force and the school officials of all kinds must be treated exactly on a par, no matter what their creed; and there must be no more discrimination against Jew or Catholic or Protestant than discrimination[6] in favor of Jew, Catholic or Protestant. Whoever makes such discrimination is an enemy of the public schools.

HYPHENATED AMERICANS.

What is true of creed is no less true of nationality. There is no room in this country for hyphenated Americanism. When I refer to hyphenated Americans, I do not refer to naturalized Americans. Some of the very best Americans I have ever known were naturalized Americans, Americans born abroad. But a hyphenated American is not an American at all. This is just as true of the man who puts “native” before the hyphen as of the man who puts German or Irish or English or French before the hyphen. Americanism is a matter of the spirit and of the soul. Our allegiance must be purely to the United States. We must unsparingly condemn any man who holds any other allegiance. But if he is heartily and singly loyal to this Republic, then no matter where he was born, he is just as good an American as anyone else.

The one absolutely certain way of bringing this nation to ruin, of preventing all possibility of its continuing to be a nation at all, would be to permit it to become a tangle of squabbling nationalities, an intricate knot of German-Americans, Irish-Americans, English-Americans, French-Americans, Scandinavian-Americans or Italian-Americans, each preserving its separate nationality, each at heart feeling more sympathy with Europeans of that nationality, than with the other citizens of the American Republic. The men who do not become Americans and nothing else are hyphenated Americans; and there ought to be[7] no room for them in this country. The man who calls himself an American citizen and who yet shows by his actions that he is primarily the citizen of a foreign land, plays a thoroughly mischievous part in the life of our body politic. He has no place here; and the sooner he returns to the land to which he feels his real heart-allegiance, the better it will be for every good American. There is no such thing as a hyphenated American who is a good American. The only man who is a good American is the man who is an American and nothing else.

I appeal to history. Among the generals of Washington in the Revolutionary War were Greene, Putnam and Lee, who were of English descent; Wayne and Sullivan, who were of Irish descent; Marion, who was of French descent; Schuyler, who was of Dutch descent, and Muhlenberg and Herkemer, who were of German descent. But they were all of them Americans and nothing else, just as much as Washington. Carroll of Carrollton was a Catholic; Hancock a Protestant; Jefferson was heterodox from the standpoint of any orthodox creed; but these and all the other signers of the Declaration of Independence stood on an equality of duty and right and liberty, as Americans and nothing else.

So it was in the Civil War. Farragut’s father was born in Spain and Sheridan’s father in Ireland; Sherman and Thomas were of English and Custer of German descent; and Grant came of a long line of American ancestors whose original home had been Scotland. But the Admiral was not a Spanish-American; and the Generals were not Scotch-Americans or Irish-Americans or English-Americans or German-Americans.[8] They were all Americans and nothing else. This was just as true of Lee and of Stonewall Jackson and of Beauregard.

When in 1909 our battlefleet returned from its voyage around the world, Admirals Wainwright and Schroeder represented the best traditions and the most effective action in our navy; one was of old American blood and of English descent; the other was the son of German immigrants. But one was not a native-American and the other a German-American. Each was an American pure and simple. Each bore allegiance only to the flag of the United States. Each would have been incapable of considering the interests of Germany or of England or of any other country except the United States.

To take charge of the most important work under my administration, the building of the Panama Canal, I chose General Goethals. Both of his parents were born in Holland. But he was just plain United States. He wasn’t a Dutch-American; if he had been I wouldn’t have appointed him. So it was with such men, among those who served under me, as Admiral Osterhaus and General Barry. The father of one was born in Germany, the father of the other in Ireland. But they were both Americans, pure and simple, and first rate fighting men in addition.

In my Cabinet at the time there were men of English and French, German, Irish and Dutch blood, men born on this side and men born in Germany and Scotland; but they were all Americans and nothing else; and every one of them was incapable of thinking of himself or of his fellow-countrymen,[9] excepting in terms of American citizenship. If any one of them had anything in the nature of a dual or divided allegiance in his soul, he never would have been appointed to serve under me, and he would have been instantly removed when the discovery was made. There wasn’t one of them who was capable of desiring that the policy of the United States should be shaped with reference to the interests of any foreign country or with consideration for anything, outside of the general welfare of humanity, save the honor and interest of the United States, and each was incapable of making any discrimination whatsoever among the citizens of the country he served, of our common country, save discrimination based on conduct and on conduct alone.

For an American citizen to vote as a German-American, an Irish-American or an English-American is to be a traitor to American institutions; and those hyphenated Americans who terrorize American politicians by threats of the foreign vote are engaged in treason to the American Republic.

PRINCIPLES OF AMERICANISM.

Now this is a declaration of principles. How are we in practical fashion to secure the making of these principles part of the very fiber of our national life? First and foremost let us all resolve that in this country hereafter we shall place far less emphasis upon the question of right and much greater emphasis upon the matter of duty. A republic can’t succeed and won’t succeed in the tremendous international stress of the modern world unless its citizens possess that[10] form of high-minded patriotism which consists in putting devotion to duty before the question of individual rights. This must be done in our family relations or the family will go to pieces; and no better tract for family life in this country can be imagined than the little story called “Mother,” written by an American woman, Kathleen Norris, who happens to be a member of your own church.

What is true of the family, the foundation stone of our national life, is not less true of the entire superstructure. I am, as you know, a most ardent believer in national preparedness against war as a means of securing that honorable and self-respecting peace which is the only peace desired by all high-spirited people. But it is an absolute impossibility to secure such preparedness in full and proper form if it is an isolated feature of our policy. The lamentable fate of Belgium has shown that no justice in legislation or success in business will be of the slightest avail if the nation has not prepared in advance the strength to protect its rights. But it is equally true that there cannot be this preparation in advance for military strength unless there is a social basis of civil and social life behind it. There must be social, economic and military preparedness all alike, all harmoniously developed; and above all there must be spiritual and mental preparedness.

SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC PREPAREDNESS.

There must be not merely preparedness in things material; there must be preparedness in soul and mind. To prepare a great[11] army and navy without preparing a proper national spirit would avail nothing. And if there is not only a proper national spirit but proper national intelligence, we shall realize that even from the standpoint of the army and navy some civil preparedness is indispensable. For example, a plan for national defense which does not include the most far-reaching use and co-operation of our railroads must prove largely futile. These railroads are organized in time of peace. But we must have the most carefully thought out organization from the national and centralized standpoint in order to use them in time of war. This means first that those in charge of them from the highest to the lowest must understand their duty in time of war, must be permeated with the spirit of genuine patriotism; and second, that they and we shall understand that efficiency is as essential as patriotism; one is useless without the other.

Again: every citizen should be trained sedulously by every activity at our command to realize his duty to the nation. In France at this moment the workingmen who are not at the front are spending all their energies with the single thought of helping their brethren at the front by what they do in the munition plant, on the railroads, in the factories. It is a shocking, a lamentable thing that many of the trade unions of England have taken a directly opposite view. I am not concerned with whether it be true, as they assert, that their employers are trying to exploit them, or, as these employers assert, that the labor men are trying to gain profit for those who stay at home at the cost of their brethren who fight in the trenches. The thing for us Americans to[12] realize is that we must do our best to prevent similar conditions from growing up here. Business men, professional men, and wage workers alike must understand that there should be no question of their enjoying any rights whatsoever unless in the fullest way they recognize and live up to the duties that go with those rights. This is just as true of the corporation as of the trade union, and if either corporation or trade union fails heartily to acknowledge this truth, then its activities are necessarily anti-social and detrimental to the welfare of the body politic as a whole. In war time, when the welfare of the nation is at stake, it should be accepted as axiomatic that the employer is to make no profit out of the war save that which is necessary to the efficient running of the business and to the living expenses of himself and family, and that the wage worker is to treat his wage from exactly the same standpoint and is to see to it that the labor organization to which he belongs is, in all its activities, subordinated to the service of the nation.

Now there must be some application of this spirit in times of peace or we cannot suddenly develop it in time of war. The strike situation in the United States at this time is a scandal to the country as a whole and discreditable alike to employer and employee. Any employer who fails to recognize that human rights come first and that the friendly relationship between himself and those working for him should be one of partnership and comradeship in mutual help no less than self-help is recreant to his duty as an American citizen and it is to his interest, having in view the enormous destruction of life in the present war, to[13] conserve, and to train to higher efficiency alike for his benefit and for its, the labor supply. In return any employee who acts along the lines publicly advocated by the men who profess to speak for the I. W. W. is not merely an open enemy of business but of this entire country and is out of place in our government.

You, Knights of Columbus, are particularly fitted to play a great part in the movement for national solidarity, without which there can be no real efficiency in either peace or war. During the last year and a quarter it has been brought home to us in startling fashion that many of the elements of our nation are not yet properly fused. It ought to be a literally appalling fact that members of two of the foreign embassies in this country have been discovered to be implicated in inciting their fellow-countrymen, whether naturalized American citizens or not, to the destruction of property and the crippling of American industries that are operating in accordance with internal law and international agreement. The malign activity of one of these embassies has been brought home directly to the ambassador in such shape that his recall has been forced. The activities of the other have been set forth in detail by the publication in the press of its letters in such fashion as to make it perfectly clear that they were of the same general character. Of course, the two embassies were merely carrying out the instructions of their home governments.

Nor is it only the German and Austrians who take the view that as a matter of right they can treat their countrymen resident in America, even if naturalized citizens of the United States, as their allies and subjects[14] to be used in keeping alive separate national groups profoundly anti-American in sentiment if the contest comes between American interests and those of foreign lands in question. It has recently been announced that the Russian government is to rent a house in New York as a national center to be Russian in faith and patriotism, to foster the Russian language and keep alive the national feeling in immigrants who come hither. All of this is utterly antagonistic to proper American sentiment, whether perpetrated in the name of Germany, of Austria, of Russia, of England, or France or any other country.

RIGHTS AND DUTIES OF CITIZENS.

We should meet this situation by on the one hand seeing that these immigrants get all their rights as American citizens, and on the other hand insisting that they live up to their duties as American citizens. Any discrimination against aliens is a wrong, for it tends to put the immigrant at a disadvantage and to cause him to feel bitterness and resentment during the very years when he should be preparing himself for American citizenship. If an immigrant is not fit to become a citizen, he should not be allowed to come here. If he is fit, he should be given all the rights to earn his own livelihood, and to better himself, that any man can have. Take such a matter as the illiteracy test; I entirely agree with those who feel that many very excellent possible citizens would be barred improperly by an illiteracy test. But why do you not admit aliens under a bond to learn to read and write within a certain[15] time? It would then be a duty to see that they were given ample opportunity to learn to read and write and that they were deported if they failed to take advantage of the opportunity. No man can be a good citizen if he is not at least in process of learning to speak the language of his fellow-citizens. And an alien who remains here without learning to speak English for more than a certain number of years should at the end of that time be treated as having refused to take the preliminary steps necessary to complete Americanization and should be deported. But there should be no denial or limitation of the alien’s opportunity to work, to own property and to take advantage of civic opportunities. Special legislation should deal with the aliens who do not come here to be made citizens. But the alien who comes here intending to become a citizen should be helped in every way to advance himself, should be removed from every possible disadvantage and in return should be required under penalty of being sent back to the country from which he came, to prove that he is in good faith fitting himself to be an American citizen.

PREPARATIVES TO PREPAREDNESS.

Therefore, we should devote ourselves as a preparative to preparedness, alike in peace and war, to secure the three elemental things; one, a common language, the English language; two, the increase in our social loyalty—citizenship absolutely undivided, a citizenship which acknowledges no flag except the flag of the United States and which emphatically repudiates all duality[16] of intention or national loyalty; and third, an intelligent and resolute effort for the removal of industrial and social unrest, an effort which shall aim equally at securing every man his rights and to make every man understand that unless he in good faith performs his duties he is not entitled to any rights at all.

The American people should itself do these things for the immigrants. If we leave the immigrant to be helped by representatives of foreign governments, by foreign societies, by a press and institutions conducted in a foreign language and in the interest of foreign governments, and if we permit the immigrants to exist as alien groups, each group sundered from the rest of the citizens of the country, we shall store up for ourselves bitter trouble in the future.

MILITARY PREPAREDNESS.

I am certain that the only permanently safe attitude for this country as regards national preparedness for self-defense is along its lines of universal service on the Swiss model. Switzerland is the most democratic of nations. Its army is the most democratic army in the world. There isn’t a touch of militarism or aggressiveness about Switzerland. It has been found as a matter of actual practical experience in Switzerland that the universal military training has made a very marked increase in social efficiency and in the ability of the man thus trained to do well for himself in industry. The man who has received the training is a better citizen, is more self-respecting, more orderly, better able to hold his own, and more willing to respect the rights of[17] others and at the same time he is a more valuable and better paid man in his business. We need that the navy and the army should be greatly increased and that their efficiency as units and in the aggregate should be increased to an even greater degree than their numbers. An adequate regular reserve should be established. Economy should be insisted on, and first of all in the abolition of useless army posts and navy yards. The National Guard should be supervised and controlled by the Federal War Department. Training camps such as at Plattsburg should be provided on a nationwide basis and the government should pay the expenses. Foreign-born as well as native-born citizens should be brought together in those camps; and each man at the camp should take the oath of allegiance as unreservedly and unqualifiedly as the men of its regular army and navy now take it. Not only should battleships, battle cruisers, submarines, ample coast and field artillery be provided and a greater ammunition supply system, but there should be a utilization of those engaged in such professions as the ownership and management of motor cars, in aviation, and in the profession of engineering. Map-making and road improvement should be attended to, and, as I have already said, the railroads brought into intimate touch with the War Department. Moreover, the government should deal with conservation of all necessary war supplies such as mine products, potash, oil lands and the like. Furthermore, all munition plants should be carefully surveyed with special reference to their geographic distribution and for the possibility of increased munition and supply factories. Finally,[18] remember that the men must be sedulously trained in peace to use this material or we shall merely prepare our ships, guns and products as gifts to the enemy. All of these things should be done in any event, but let us never forget that the most important of all things is to introduce universal military service.

But let me repeat that this preparedness against war must be based upon efficiency and justice in the handling of ourselves in time of peace. If belligerent governments, while we are not hostile to them but merely neutral, strive nevertheless to make of this nation many nations, each hostile to the others and none of them loyal to the central government, then it may be accepted as certain that they would do far worse to us in time of war. If they encourage strikes and sabotage in our munition plants while we are neutral it may be accepted as axiomatic that they would do far worse to us if we were hostile. It is our duty from the standpoint of self-defense to secure the complete Americanization of our people. To make of the many peoples of this country a united nation, one in speech and feeling and all, so far as possible, sharers in the best that each has brought to our shores.

AMERICANIZATION.

The foreign-born population of this country must be an Americanized population—no other kind can fight the battles of America either in war or peace. It must talk the language of its native-born fellow citizens, it must possess American citizenship and American ideals. It must stand firm by its oath of allegiance in word and deed and must show that in very fact it has renounced[19] allegiance to every prince, potentate or foreign government. It must be maintained on an American standard of living so as to prevent labor disturbances in important plants and at critical times. None of these objects can be secured as long as we have immigrant colonies, ghettos, and immigrant sections, and above all they cannot be assured so long as we consider the immigrant only as an industrial asset. The immigrant must not be allowed to drift or to be put at the mercy of the exploiter. Our object is not to imitate one of the older racial types, but to maintain a new American type and then to secure loyalty to this type. We cannot secure such loyalty unless we make this a country where men shall feel that they have justice and also where they shall feel that they are required to perform the duties imposed upon them. The policy of “Let alone” which we have hitherto pursued is thoroughly vicious from two standpoints. By this policy we have permitted the immigrants, and too often the native-born laborers as well, to suffer injustice. Moreover, by this policy we have failed to impress upon the immigrant and upon the native-born as well that they are expected to do justice as well as to receive justice, that they are expected to be heartily and actively and single-mindedly loyal to the flag no less than to benefit by living under it.

We cannot afford to continue to use hundreds of thousands of immigrants merely as industrial assets while they remain social outcasts and menaces any more than fifty years ago we could afford to keep the black man merely as an industrial asset and not as a human being. We cannot afford to[20] build a big industrial plant and herd men and women about it without care for their welfare. We cannot afford to permit squalid overcrowding or the kind of living system which makes impossible the decencies and necessities of life. We cannot afford the low wage rates and the merely seasonal industries which mean the sacrifice of both individual and family life and morals to the industrial machinery. We cannot afford to leave American mines, munitions plants and general resources in the hands of alien workmen, alien to America and even likely to be made hostile to America by machinations such as have recently been provided in the case of the two foreign embassies in Washington. We cannot afford to run the risk of having in time of war men working on our railways or working in our munition plants who would in the name of duty to their own foreign countries bring destruction to us. Recent events have shown us that incitements to sabotage and strikes are in the view of at least two of the great foreign powers of Europe within their definition of neutral practices. What would be done to us in the name of war if these things are done to us in the name of neutrality?

Justice Dowling in his speech has described the excellent fourth degree of your order, of how in it you dwell upon duties rather than rights, upon the great duties of patriotism and of national spirit. It is a fine thing to have a society that holds up such a standard of duty. I ask you to make a special effort to deal with Americanization, the fusing into one nation, a nation necessarily different from all other nations, of all who come to our shores. Pay heed[21] to the three principal essentials: (1) The need of a common language, with a minimum amount of illiteracy; (2) the need of a common civil standard, similar ideals, beliefs and customs symbolized by the oath of allegiance to America; and (3) the need of a high standard of living, of reasonable equality of opportunity and of social and industrial justice. In every great crisis in our history, in the Revolution and in the Civil War, and in the lesser crises, like the Spanish war, all factions and races have been forgotten in the common spirit of Americanism. Protestant and Catholic, men of English or of French, of Irish or of German descent have joined with a single-minded purpose to secure for the country what only can be achieved by the resultant union of all patriotic citizens. You of this organization have done a great service by your insistence that citizens should pay heed first of all to their duties. Hitherto undue prominence has been given to the question of rights. Your organization is a splendid engine for giving to the stranger within our gates a high conception of American citizenship. Strive for unity. We suffer at present from a lack of leadership in these matters.

Even in the matter of national defense there is such a labyrinth of committees and counsels and advisors that there is a tendency on the part of the average citizen to become confused and do nothing. I ask you to help strike the note that shall unite our people. As a people we must be united. If we are not united we shall slip into the gulf of measureless disaster. We must be strong in purpose for our own defense and bent on securing justice within our borders.[22] If as a nation we are split into warring camps, if we teach our citizens not to look upon one another as brothers but as enemies divided by the hatred of creed for creed or of those of one race against those of another race, surely we shall fail and our great democratic experiment on this continent will go down in crushing overthrow. I ask you here to-night and those like you to take a foremost part in the movement—a young men’s movement—for a greater and better America in the future.

ONE AMERICA.

All of us, no matter from what land our parents came, no matter in what way we may severally worship our Creator, must stand shoulder to shoulder in a united America for the elimination of race and religious prejudice. We must stand for a reign of equal justice to both big and small. We must insist on the maintenance of the American standard of living. We must stand for an adequate national control which shall secure a better training of our young men in time of peace, both for the work of peace and for the work of war. We must direct every national resource, material and spiritual, to the task not of shirking difficulties, but of training our people to overcome difficulties. Our aim must be, not to make life easy and soft, not to soften soul and body, but to fit us in virile fashion to do a great work for all mankind. This great work can only be done by a mighty democracy, with these qualities of soul, guided by those qualities of mind, which will both make it refuse to do injustice to any other nation, and also enable it to hold its own against aggression by any other nation. In[23] our relations with the outside world, we must abhor wrongdoing, and disdain to commit it, and we must no less disdain the baseness of spirit which lamely submits to wrongdoing. Finally and most important of all, we must strive for the establishment within our own borders of that stern and lofty standard of personal and public neutrality which shall guarantee to each man his rights, and which shall insist in return upon the full performance by each man of his duties both to his neighbor and to the great nation whose flag must symbolize in the future as it has symbolized in the past the highest hopes of all mankind.

This is truly wondrous. The basic element of all life finally captured in way that’s identifiable! This remarkable photo of a SINGLE ATOM (trapped by electric fields) has just been awarded the top prize in a well-known science photography competition. The photo is titled “Single Atom in an Ion Trap” and was shot by David Nadlinger at the University of Oxford in England. (For the record it’s a single positively-charged strontium atom)