Month: May 2025

Some mighty hard men at work

Kelsey’s Rifle by Edmund Lewis

John Kelsey, the stage driver, was prevailed upon to accept the desperado as a fare and he wasn’t exactly happy about it. His injured leg was still bothering him and he hadn’t slept well. The rough-and-tumble Montanan didn’t much like having to tote Bill’s sorry ass to Virginia City but he needed the money, needed Bill’s fare.

It was cold that morning in Montana. Small, hard snowflakes were blowing, portending the storm to come. Things went reasonably well on the road, though the ruts were slick with early morning ice and the stage was bouncing and skidding along, but Kelsey had a strong team and was making good time. They would be in Virginia City in a few hours.

Bad Bill was riding with a salesman and two other passengers, one a lady. Bill was swigging from the bottle of rotgut he’d stuck in his pocket to ward off the cold of that winter morning. By the time the coach had reached Brown’s Bridge station on the Big Hole River, Bad Bill was drunk and bullying the other passengers.

In the melee that ensued, Kelsey took on Bill and threw him into the stage yard. Bill responded by pulling his Colt and taking a shot at him. Bad move – and Bill’s last. Kelsey reached up and pulled his rifle from the stage’s boot and shot him dead with the big .45-75 Winchester.

These events, as reported in the Virginia City newspaper the next day, add to the rich history of John Kelsey’s 1 of 100 Model ’76 Winchester. He had been given the rifle by Sam Benham, a Butte mining official, when the two were hunting for winter meat. Kelsey shot an elk with his single-shot Sharps, while Benham, who had an untimely attack of buck fever, stood idly by. Kelsey grabbed Benham’s Winchester and in short order dropped three more elk with the repeater.

“Hell,” cried Benham, “a man that shoots like that needs a better gun. Take it . . . it’s yours!”

Suddenly John Kelsey became the second owner of this historic Winchester rifle.

The rifle, serial number 713, is by far the most well-known Model 1876 1 of 100. On November 15, 1877 it was shipped by Winchester to the Butte Rifle Club in the company of several other 1 of 100s and 1 of 1000s. Sam Benham, along with William A. Clark, one of the Montana Copper Kings, used the rifles in shooting matches at the club.

Kelsey’s rifle is an early First Model 1876, a so-called “Open Top” because of the lack of a dust cover. It has a set trigger and came with sling swivels from the factory. The rifle is in surprisingly good condition for having been carried in the boot of Kelsey’s stage for many years.

The early Model 1876 guns were .45-75 W.C.F. caliber and later guns were chambered in the then more popular .45-60 W.C.F. The earliest Model 1873 premium rifles were simply engraved 1 of 1000 in Arabic. Later rifles had “One of One Thousand” or “One of One Hundred” engraved with an arabesque and foliate border in a panel on the top flat of the octagon barrel, just forward of the receiver.

The rifles were stocked in premium, highly figured and finished walnut. The 1 of 1000 rifles had platinum barrel bands inlaid at the breech and muzzle end. The receivers of most of these rifles were colorfully case hardened, and the blued barrels and magazines received extra finish. Set triggers were often installed, and special engraving or gold plating could be ordered on request. Winchester had a policy of providing whatever the customer desired and would pay for.

To this day Kelsey’s rifle is still accurate, and the author has shot two-inch groups with handloads at 100 yards.

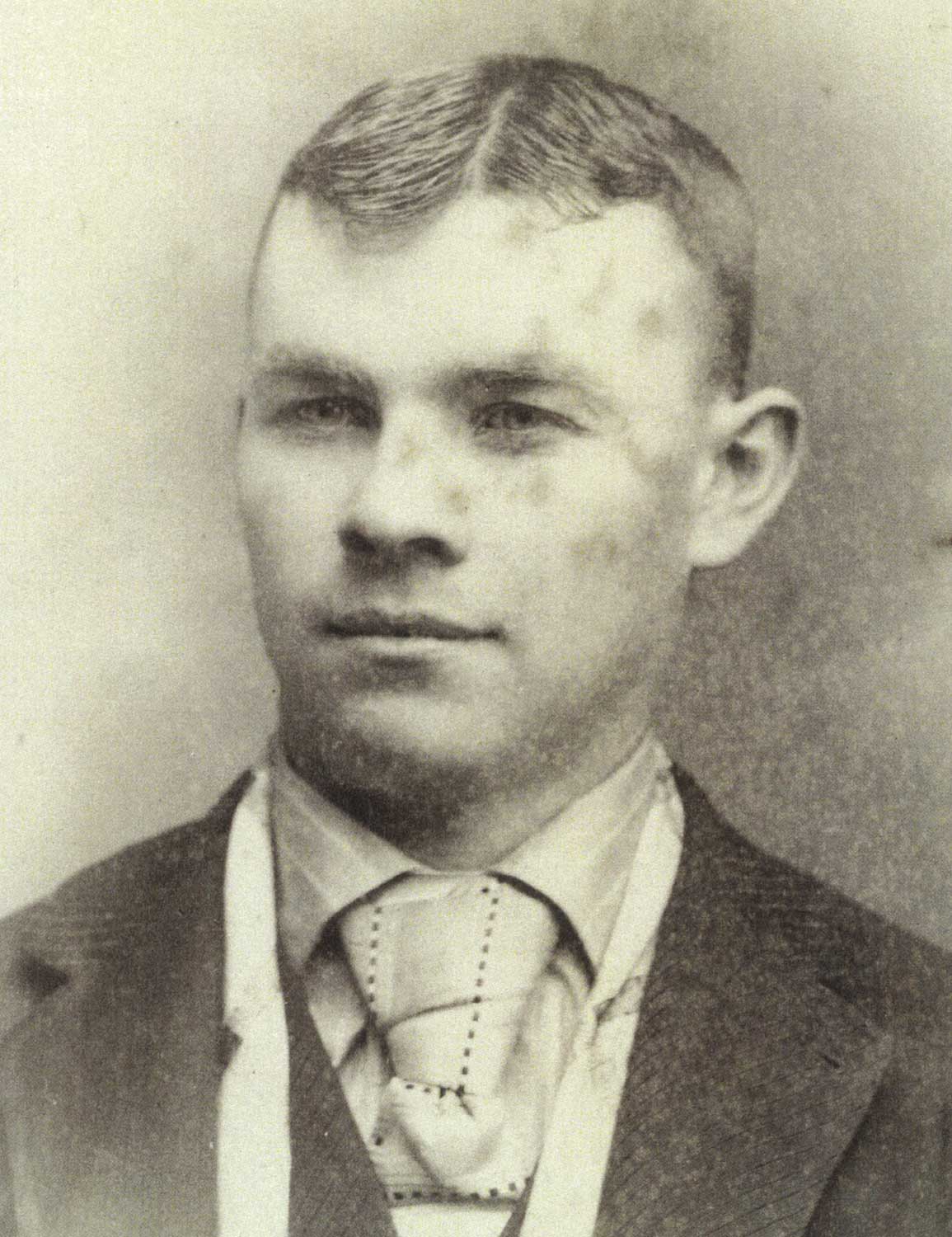

The history of John Kelsey was related by his grandson, John Ballard, in March 1942 in The Montana News Association and was repeated by James E. Serven in an article in the American Rifleman in September of 1957:

“ . . . his early years were spent in the mountains, before the arrival of the railroads in that region. His father, Eli Kelsey, became the historian of the Mormon Church after his arrival in Utah in 1848.

Shortly thereafter, Brigham Young ordered a group of young men to leave everything and to ‘go on a mission, without script or purse’ to preach the Mormon gospel. A number of men, including Eli, refused, fearing they would lose all their worldly goods to someone else while in the field.

“Along with the others, Eli was cut off from the church and from young John, who was ten at the time. From that day on little “Jack” Kelsey was a marked boy and was called an “apostate” by his schoolmates. He often heard this epithet on the way to and from school, and was frequently forced to fight his Mormon schoolmates. John paid dearly for his father’s refusal to obey church elders, but he learned lessons that later stood him in good stead on the roads and in the mining camps of Montana.

“By 1880 Kelsey had enough of Utah life and set out for Montana. He bought a dead-axe wagon, drove to Red Rock, which was then at the end of the rail line, and engaged in hauling passengers and freight . . .”

Kelsey later became a stage driver who occasionally had to fight his passengers for the fares they owed him. One of them was an actor named Adams who traveled about the territory with his troupe. They played Sheridan, Montana as their first town, but Adams did not pay Kelsey, telling him he “would settle up” in Virginia City. There, however, Adams refused to pay. Kelsey challenged him for his fare and in the ensuing fight left the much larger actor on the floor. Kelsey ended up in the hands of the city marshal. He avoided jail and was awarded the money owed him by the judge who fined Adams for “trying to cheat the boy out of his fare.”

On another trip Kelsey and two passengers, men named Rafferty and Thompson, were set upon and robbed by highwaymen on the road between Deer Lodge and Helena. Preferring not to fight, the passengers threw their pistols in the brush.

On their arrival in Helena, one of the men, who had concealed his purse from the robbers, refused to pay Kelsey. That evening the stage driver confronted him as he sat playing cards at the Centennial Hotel with a large pile of chips before him. Kelsey put the man down and took his due from the table.

Later in life Kelsey became a bailiff for the Federal Court, a guard at the U.S. Marshal’s office, and a lookout for a gambling and bawdy house in Butte. He was still one tough customer, and his rifle continued to serve him well. Upon his retirement, Kelsey hung the Winchester on a rack of antlers above the fireplace in his home in Butte.

Early in their planning for the Model 1873, Winchester officials decided to market the rifle to shooters who were willing to pay for a high-quality, extremely accurate gun.

According to a note written in 1919 by George K. Walker, an early Winchester historian, the man primarily responsible for the 1 of 1000 program was James E. Stetson, a well-known precision shooter who worked for Winchester in the 1870s as a contractor supplying gun barrels.

He traveled throughout the country representing the company at tournaments and shooting matches, competing against other marksmen such as Wild West showman Doc Carver and Buffalo Bill Cody. Competitive rifle shooting at the time was a popular pastime, with many matches drawing thousands of people.

In 1873 Winchester announced a program to produce exceptionally accurate rifles that would sell for substantially more than their standard guns. A Model 1873 rifle in those days cost $17. The company manufactured 136 Model 1873 1 of 1000 rifles, which sold for $80 to $100 each.

That was a great deal of money back then, similar to a sportsman now paying $5,000 for a custom-made rifle. Rifles that were deemed slightly less accurate were sold as 1 of 100 guns for $60 to $75, depending on finish. In the same fashion these two grades of premium rifles were also produced in the Model 1876.

At the Winchester plant, of every 100 rifles tested, the one with the most accurate barrel was set aside. This continued until 1,000 rifles had been judged. Then, of the ten that had been set aside, one was engraved as “1 of 1000” while the other nine were marked “1 of 100.”

Ultimately, Winchester only produced eight “1 of 100” rifles, which were listed in the 1875 catalog but never again advertised. Winchester realized that in promoting these extremely accurate rifles, they were implying that their standard guns were inferior. As one old Winchester worker stated, “Hell, they were all accurate!” Oliver F. Winchester, who was acutely aware of marketing and profits, soon dropped the program.

These special rifles then fell into obscurity, known only to a few collectors and dealers until the release of the motion picture Winchester ’73 in 1950.

The movie relived the story of a rifle that had been used to win a target match, then was stolen and recovered only to be stolen again before it was returned to its rightful owner. Starring James Stewart, Shelley Winters and Dan Duryea, Winchester ’73 was well received by moviegoers and critics alike, and was named the Best Written American Western by the Writers Guild of America.

The film, partly based on fact, was popular not only with Winchester fans, but with gun collectors and those interested in the Old West.

Universal Pictures, in conjunction with Winchester Repeating Arms Company, conducted a nationwide search for Model 73 rifles and offered a new Model 1894 to the first 20 individuals who reported ownership of a 1 of 1000.

More than 150,000 “WANTED!” posters were distributed nationwide to newspapers, radio stations and rifle clubs affiliated with the NRA, in addition to 20,000 chiefs of police. The search was extraordinarily successful and more than 20 Model 73 “1 of 1000s” were reported as well as six Model 1876 “1 of 1000s.” Although their existence was known, no Model 73 or Model 76 “1 of 100s” surfaced.

Universal Pictures and Winchester’s 1 of 1000 search clearly exceeded all expectations. Their program to advertise the motion picture stimulated the entire field of gun collecting and brought the Winchester rifles to the attention of collectors and the public at large.

A final press release in the fall of 1950 by Universal Pictures publicist William Depperman reported the results of the search. It proved to be prophetic . . .

“From obscurity these unique ‘One of One Thousand’ Winchester Model 1873 rifles have graduated in only five months into one of the most sought after collector’s items in the country. Even garden variety Model 1873’s have doubled in price in the last few months.”

Depperman predicted the rifles would continue to increase in value (they have, and to levels he could hardly have imagined) and that the new interest in Winchesters would also generate great enthusiasm for gun collecting in general.

Upon John Kelsey’s death in April, 1929, his gun was passed down to his grandson. The rifle resurfaced during the Winchester ’73 search and was one of the “discovery” rifles reported to Winchester and Universal Pictures at that time.

The historic and detailed connection to a very colorful character of the Old West, who used a rifle as it was meant to be used, makes this Winchester more than just a fine gun. It’s an important link to our past and represents a part of our American heritage.

My interest in Winchester rifles began at age 15 when I purchased John Parson’s book, The First Winchester. I was fascinated by his stories of the early Winchester carbines and rifles, and the western characters and cowboys who used them. I was enchanted by Parson’s comments on, and illustrations of, the Winchester 1 of 1000s and 1 of 100s, but could only dream of having one.

Years would pass before I was able to purchase my first Winchester, a beat-up Model 1876 that cost $10. This old gun ignited a collecting fire that has yet to be quenched. Many more years would go by before I acquired the Model 1876 1 of 100 rifle that is the subject of this story.

I was determined to learn everything about the men who owned the rifle. Although my quest took several years, I succeeded in tracing every individual, 12 in all, including Sam Benham and John Kelsey.

Of the eight Model 1876 1 of 100s presently known, John Kelsey’s rifle is by far the most historic. The 1 of 1,000 rifles were produced in greater numbers and are much less rare, though all of these premium Winchester rifles are extremely desirable and highly sought-after by collectors.

Because of its rarity, condition and provenance, John Kelsey’s rifle is now valued at more than $400,000. Benham, the original owner, paid $112.50 for it.

My ultimate dream in gun collecting was to own the quartet of both Model 1873 and 1876 1 of 1,000s and 1 of 100s. It took decades but I reached my goal and they’re illustrated in my book, The Story of the One of One Thousand and One of One Hundred Rifles. ‘

Coffee anyone?

The Pistol FP-45 Liberator

We humans are quick to immortalize significant superlatives. The world’s largest rubber band ball weighed 8,200 lbs. The planet’s longest pizza stretched some 1.32 miles. The most candles extinguished by a single fart was five. In the spring of 1945, however, American aircrews operating over Japan set another, darker record.

The Setting

March 10, 1945 was a Saturday. Adolf Hitler had but 51 days to live. On the other side of the world, wartime Tokyo hummed along as it normally had. Men and women toiled in myriad tiny cottage workshops churning out the myriad bits of kit needed to keep the massive Japanese war machine hurtling toward oblivion. At least that’s what the historians tell us.

During World War II strategic bombing was just finding its legs. For the first time in human history, the planet was tasting total war on an industrial scale. Existential fights between nation states are as old as man. In 1945, however, we finally had the tools to take it to the next level.

The carnage was easily justified. Japan started the war at Pearl Harbor with the cold-blooded murder of 2,403 Americans on December 7, 1941. Three years later, veritable rivers of blood had been shed to get Army Air Corps B29 Superfortress heavy bombers within range of the Japanese homeland. The American people were whipped up into a proper frenzy. We wanted some payback.

The B29 represented the single most expensive weapons program in military history at the time of its deployment. Each massive 99-foot bomber cost $639,000 back in 1945. That’s about $9.3 million today. For that money the American taxpayer got an airplane sporting a dozen .50-caliber machineguns, cruised at 220 mph and carried up to 20,000 lbs. of bombs.

General Curtis LeMay owned these things and he experimented with a variety of tactics and bomb loads in an effort at maximizing the big shiny bombers’ destructive potential. Conventional attacks from great altitude using high explosive general purpose bombs or incendiaries were typically so inaccurate or dispersed as to be relatively ineffective. After several raids of several flavors by B29s on the capital city of Tokyo, the Japanese had suffered some 1,292 deaths. This lulled the Japanese authorities into a false sense of security.

One million seven hundred thousand of Tokyo’s total population had been evacuated to safer areas outside the city. However, many poor rural peasants had moved in to take their places. On this particular weekend, Tokyo, Japan, was the most congested space on earth.

Tactical Details

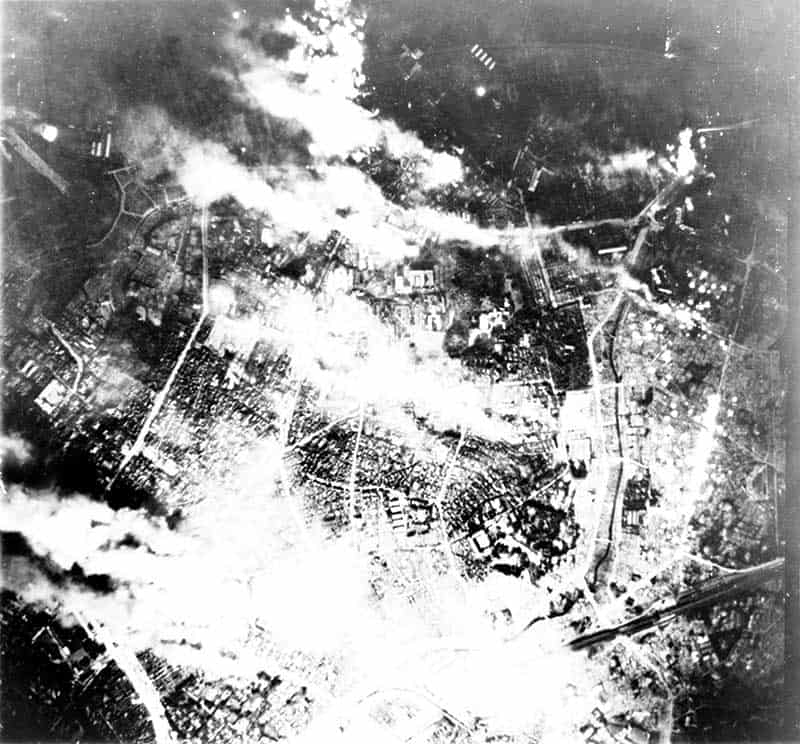

Previous attacks had taken place from high altitude in daytime via large formations. This raid, code-named Operation Meetinghouse, would be flown by a stream of individual aircraft operating between 5,000 and 7,000 feet in total darkness. Two hundred seventy-nine Superfortresses made it to the target carrying 1,510 tons of ordnance. Their altitudes were carefully selected to be above the effective small arms range yet below the optimal altitude for large-caliber anti-aircraft guns. Japanese night fighters were caught completely unawares. At 12:08 a.m. on March 10, the first pathfinder aircraft appeared over the city carrying M47 white phosphorous bombs.

These first aircraft, operated by the best crew available, painted a gigantic flaming “X” across the middle of Tokyo. A stream of follow-on planes packing M69 incendiary cluster bombs aimed for assigned portions of the “X.” When combined with prevailing surface winds of between 45 and 60 miles per hour, the end result was apocalyptic.

The M69 was simply diabolical. Developed by the Standard Oil Company at the behest of the Office of Scientific Research and Development, the M69 consisted of a 3″ plain steel pipe of hexagonal cross section that was 20″ long. Each incendiary bomblet weighed about 6 lbs. and was filled with jellied gasoline. M69s were packed 38 to a cluster munition. Upon impact with the ground, a black powder charge fired the flaming filling some 100 feet into the air with predictable effects.

The Butcher’s Bill

The resulting firestorm obliterated 16 square miles of Tokyo, destroying some 267,171 buildings in the process. More than a million Japanese were rendered homeless. Around 100,000 people died … in about three hours. Operation Meetinghouse sets the record for the most human beings killed by other humans in such a brief time. It was worse than the nuclear strikes.

Firemen gave up in the first half hour. Ninety-six fire engines were incinerated. Macadam and glass were liquified in the heat. The rivers running through Tokyo boiled. Rescue workers toiled day and night for 25 days collecting the bodies.

Follow-on aircrews had to go on oxygen to avoid the stench of burnt flesh. A dozen Superfortreses were lost with the loss of 96 aviators. The Japanese surrendered five months later. Modern man has forgotten the true nature of total war.

Bill was morose, angry really, as only a drunk can be when things are not going his way. “Bad Bill,” as he was known, had been causing big trouble in Butte and the local lawmen set out to change his address whether he liked it or not. The city fathers wanted him gone – and quickly. Gone on the stage the next morning. The coach was leaving for Virginia City and good riddance to Bill.

Bill was morose, angry really, as only a drunk can be when things are not going his way. “Bad Bill,” as he was known, had been causing big trouble in Butte and the local lawmen set out to change his address whether he liked it or not. The city fathers wanted him gone – and quickly. Gone on the stage the next morning. The coach was leaving for Virginia City and good riddance to Bill.