Month: November 2024

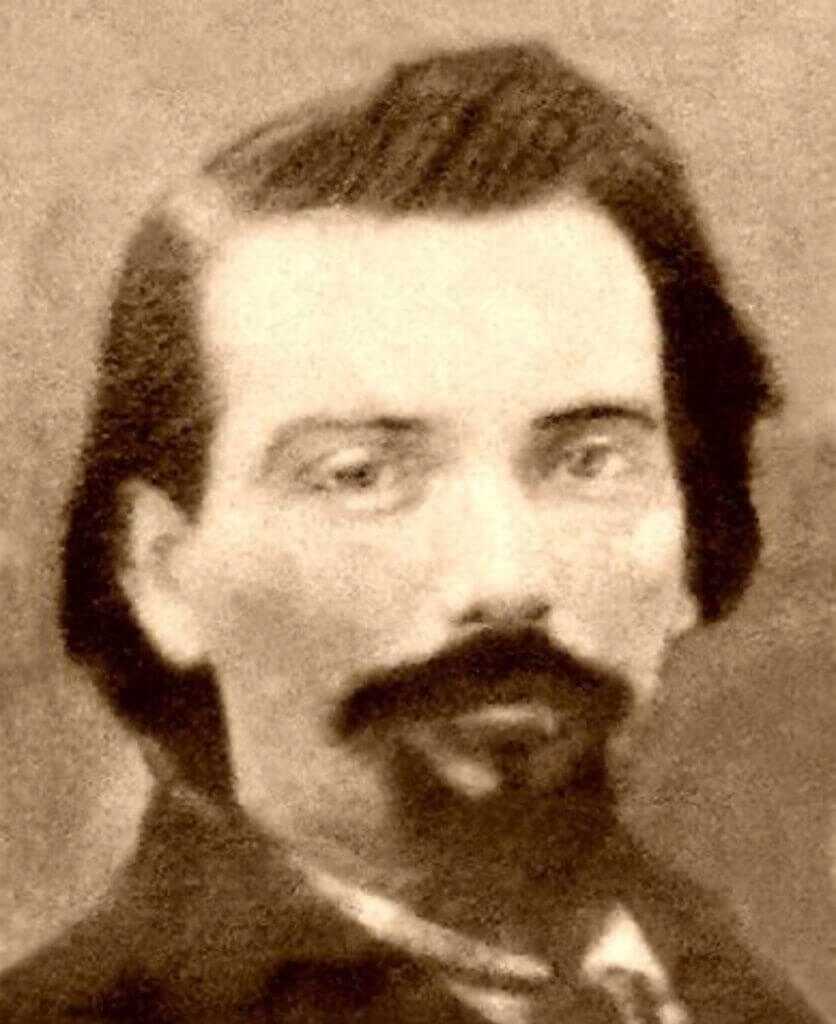

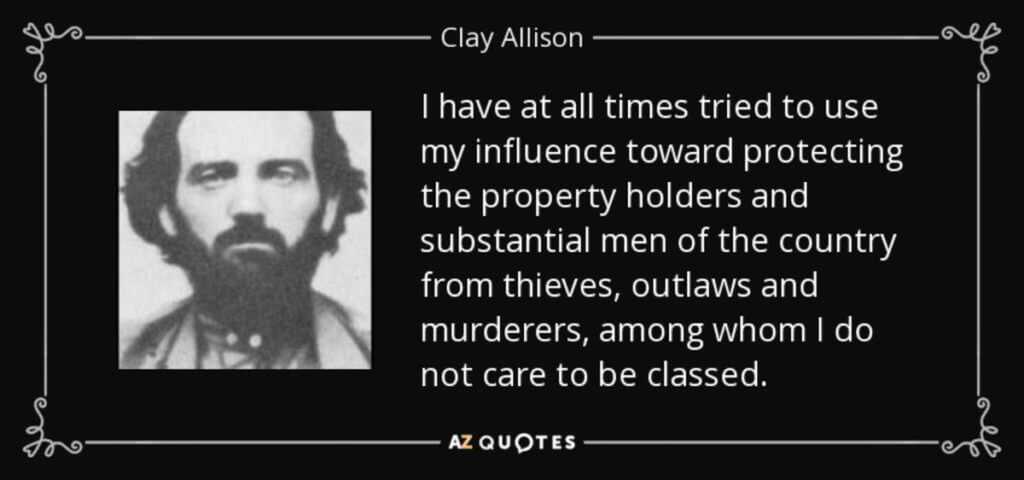

The archetypal image of the flinty-eyed Western gunfighter, his fingers twitching over the butt of a Colt revolver, came to define an era. As is so often the case with archetypes, however, reality bore little similarity to the embellished tales from the pulp novels of the day. An exception, however, was the shootist, Clay Allison.

Soldier, Rancher, Gunfighter, Psychopath

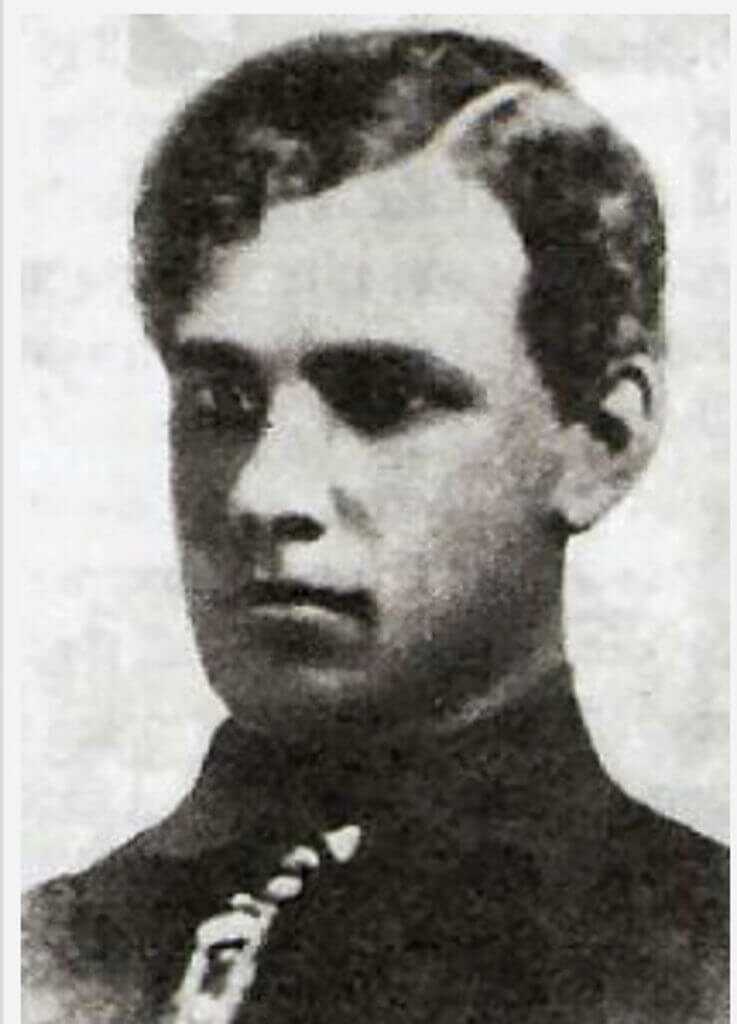

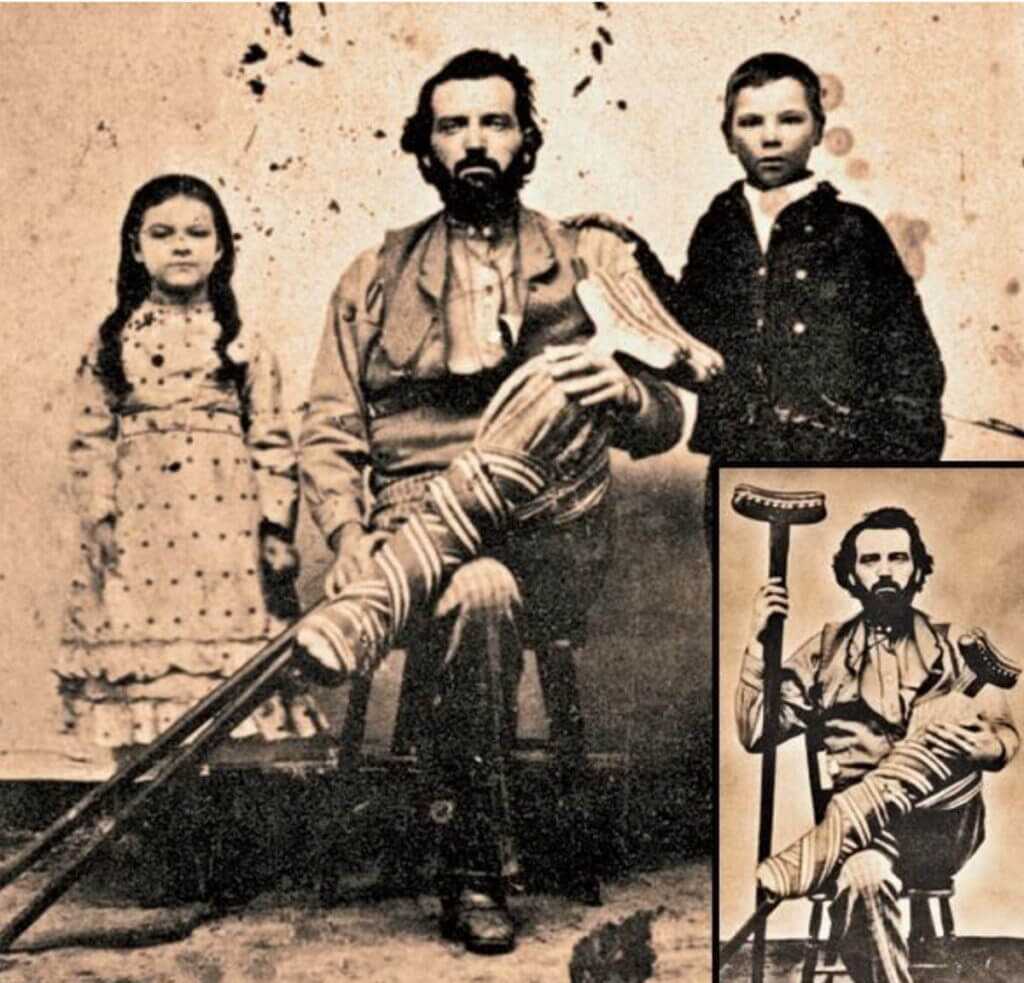

Robert Clay Allison was born in September 1841 in Waynesboro, Tennessee, the fourth of nine children. Clay’s father Jeremiah Scotland Allison was a bi-vocational Presbyterian minister who also raised sheep and cattle. Clay worked on the family farm until the outbreak of the American Civil War.

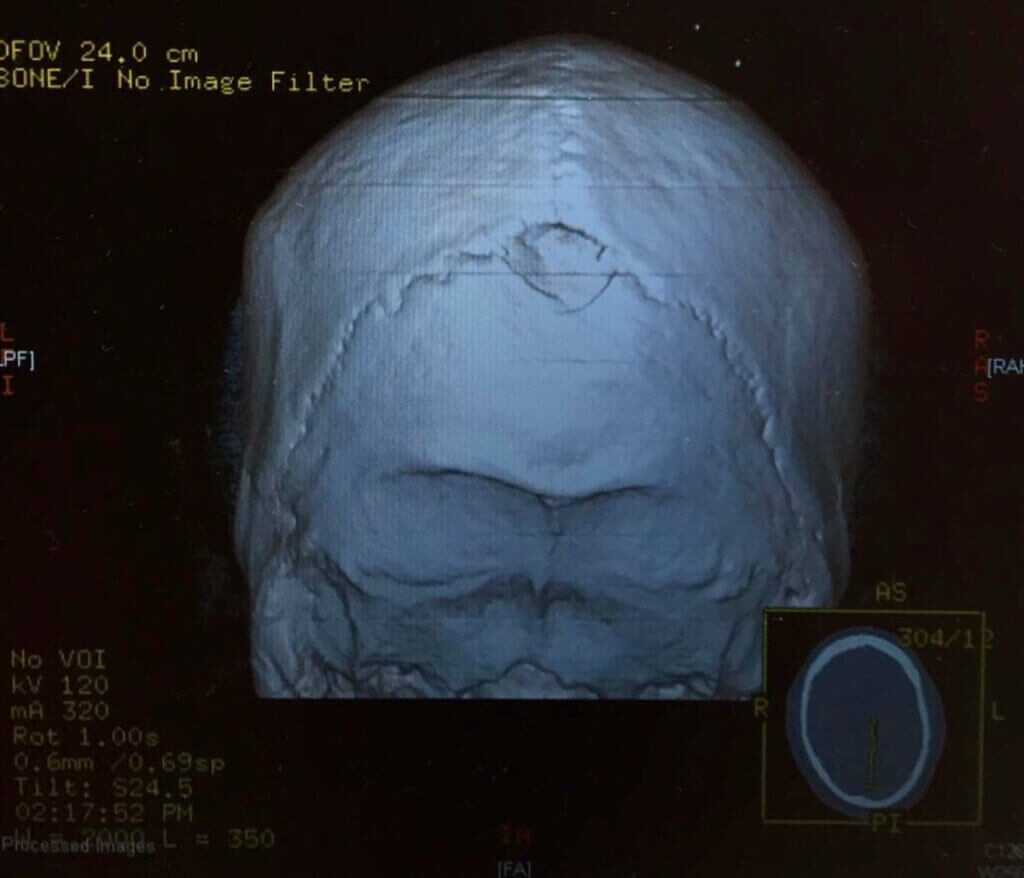

Growing up on a mid-19th century Tennessee farm was hard. Clay was afflicted with a congenital club foot and at some point had received a mighty blow to the head. This injury left him with a visible divot in his skull and some fascinating personality traits.

The human brain is the most amazing machine. When you hold a fresh one for real it is remarkably insubstantial, kind of like really thick Jell-O.

The human brain is the most amazing machine. When you hold a fresh one for real it is remarkably insubstantial, kind of like really thick Jell-O.The human brain is the most complex mechanism in the known universe. A typical adult brain weighs about three pounds and is predominantly fat. The brain generates about 23 watts of power and consumes about one-fifth of the body’s total blood and oxygen. The brain is comprised of some 100 billion neurons and features 100,000 miles of blood vessels. This remarkable device can reason, scheme, love, create and survive.

The normal function of the brain is characterized by a yin and yang of impulses and inhibitions that are even today poorly understood. When everything is operating correctly you get a normal well-adjusted productive citizen. Let some of those inhibitory functions be traumatically damaged, however, and you get Clay Allison.

Allison’s Exploits

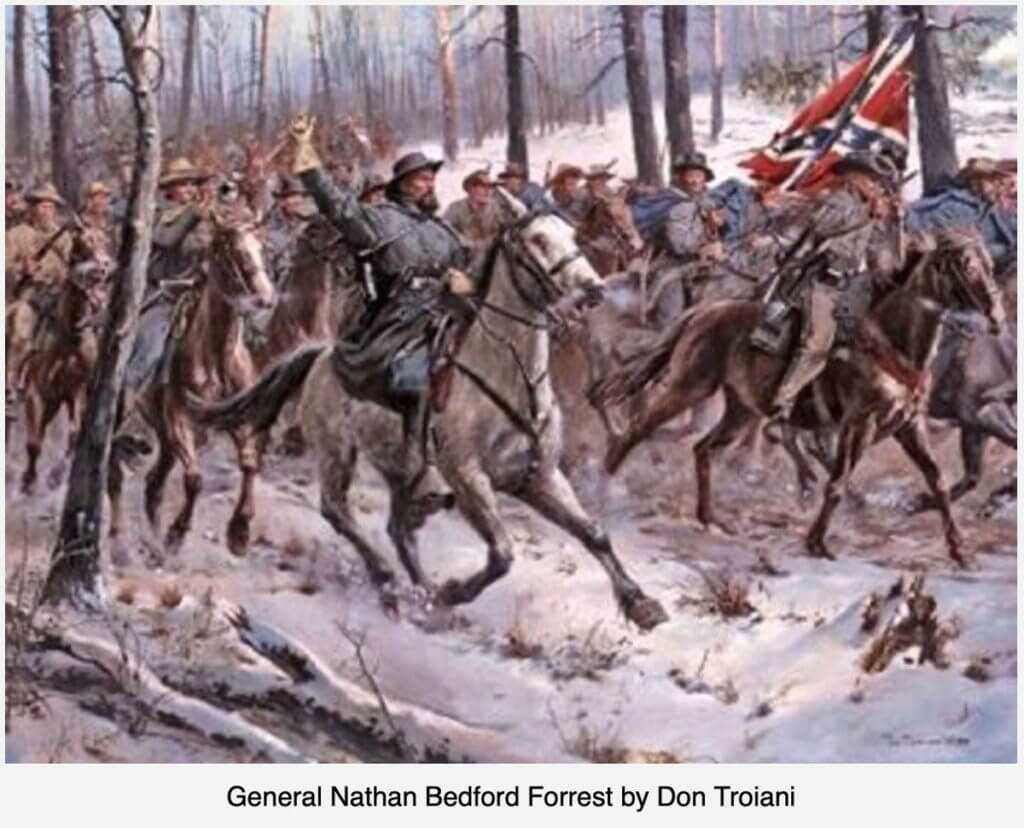

In October 1861 Allison enlisted into the Confederate Army with CPT WH Jackson’s artillery battery. Three months later he was discharged. His discharge papers stated, “Emotional or physical excitement produces paroxysmal of a mixed character, partly epileptic and partly maniacal,” whatever that actually means. However, less than a year later Allison signed on with the 9th Tennessee Cavalry under Nathan Bedford Forrest. Allison rode with Forrest until the end of the war.

Inspired by Forrest, Allison grew a similar Van Dyke beard that he wore for years. After surrendering to the Federals at Gainesville, Alabama, Allison was convicted of spying and sentenced to death. The night before sentence was to be served he purportedly killed a guard and escaped.

What followed was a most remarkable life of action, adventure, and wanton gunplay. Upon returning to civilian life, Allison joined the local Ku Klux Klan. Back home on his family farm in Tennessee Allison confronted a Union corporal from the 3rd Illinois Cavalry who had paid a call with mischievous intent. Allison retrieved a long gun and calmly cut the man down.

Settling Squabbles

Allison got into a disagreement over the fee for portage across the Red River in Texas and beat the ferryman, one Zachary Colbert, senseless as a result. Nine years later he met the ferryman’s nephew, a gunfighter of some renown named Chunk Colbert, with bloody results. Hold that thought.

During a stint in Texas, Allison got into a disagreement with a neighbor named Johnson over usage rights to a local watering hole. Allison dug a grave and entered the hole along with Johnson and a brace of Bowie knives. The winner retained access to the water. The loser retained access to the hole. The club-footed, brain-damaged Clay Allison lived to fight another day.

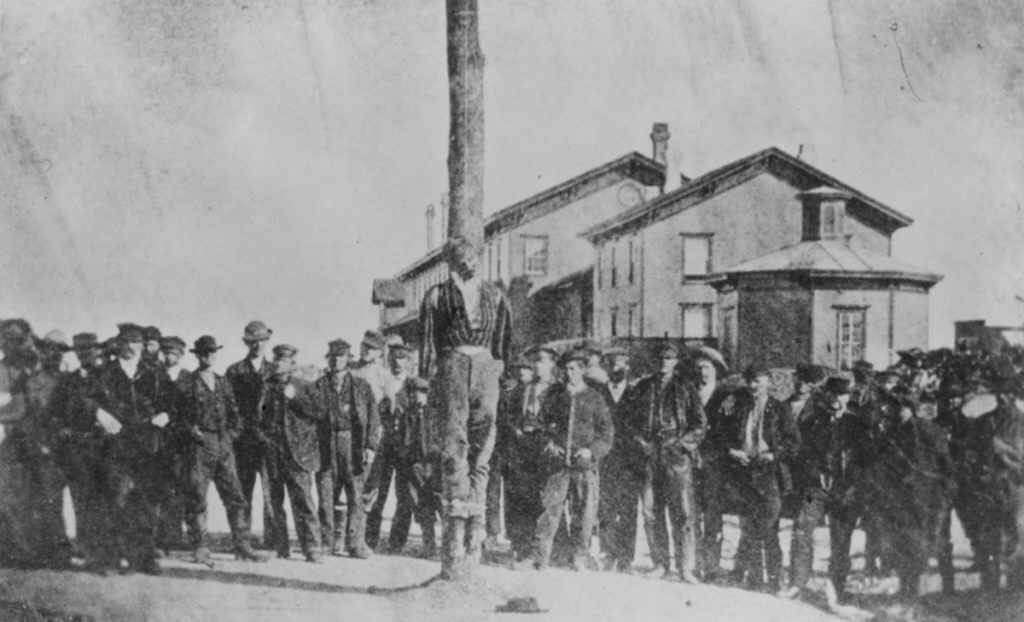

Allison had a fairly binary view of frontier justice, and he didn’t manage liquor well. In 1870 a ne’er-do-well named Charles Kennedy was jailed for robbing and killing overnight guests at his rural cabin. Allison felt that the wheels of justice were turning too slowly so he gathered some buddies, broke into the jail, and appropriated the hapless Kennedy. Allison then proceeded to lash the man to his horse and drag him back and forth along the main street until his body was a lifeless bloody pulp. Still not satisfied, Allison severed the man’s head and carried it in a sack 29 miles to the town of Cimarron. There he staked Kennedy’s head on a fence outside what later became the St. James Hotel.

Allison accidentally shot himself in the foot while trying to steal a dozen government mules. Though he recovered from the injury it left him with a noticeable permanent limp.

Just in case anybody thought of denigrating the man over his physical shortcomings, Allison was legendarily accomplished with both a knife and a handgun. On two different occasions Allison, while drunk, threw his Bowie knife and pinned men to the wall by their shirts. The first was a county clerk named John Lee. The second was a local attorney named Melvin Mills. In both cases, the men were otherwise unharmed.

The Art of the Gunfight

By 1874, Clay Allison had a reputation. Chunk Colbert, the nephew of the ferryman mentioned earlier, purportedly had six kills to his credit when he came looking to make Allison his seventh. The two men met in a local saloon and spent most of a day together drinking and gambling on horse races.

That evening Colbert invited Allison to join him at an overnight stage stop called Clifton House on the Canadian River. Prior to this fateful meal, the local sheriff had accidentally shot and killed a Clifton House waiter while trying unsuccessfully to apprehend Chunk Colbert.

Both men were wary, but by all accounts, they enjoyed an expansive meal together. Upon taking their seats Colbert set his hogleg in his lap, while Allison laid his Peacemaker on the table alongside his plate. The meal complete, Colbert thumbed back his hammer to kill Allison. However, Mr. Murphy is seldom far from enterprises of this sort. Colbert’s muzzle caught on something underneath the table, and his shot went wide. Allison raised his roscoe and shot Colbert through the head at contact range.

Friends later asked Allison why he ever accepted an invitation to dinner from a man so clearly bent upon killing him. Allison responded, “Because I didn’t want to send a man to hell on an empty stomach.”

The Gun

The Colt Model 1873 Peacemaker attained a larger-than-life reputation in the hands of gunfighters like Clay Allison. Lots of companies made sidearms during this tumultuous period in lots of different calibers. However, it was the Colt .45 that came to define the genre. The many splendored motivations behind this rarefied reputation were fully deserved.

Sam Colt devised his revolver action during a voyage as a young seaman on the brig Corvo. Intrigued by the action of the ship’s capstan, young Sam adapted the same mechanism into a rotating handgun action and changed the world.

It’s tough to quantify the secret sauce that Sam Colt used to make his eponymous revolver so awesome.

The gracefully curved butt looks so antiseptic and mechanical, yet it fits my own hand better than that of any modern plastic pistol. The single action requires a little attention, but through six rounds I can run mine almost as well as I might a Glock.

The Rest of the Story

Clay Allison shot his way into and out of trouble on several occasions after he executed Chunk Colbert over a meal. He also had a fascinating habit of getting liquored up and riding into town wearing nothing but his gunbelt. In November of 1875, he arrived in Cimarron in just such a state to celebrate his shooting of Francisco “Pancho” Griego. Allison performed some kind of war dance at the scene of the recent killing with a red ribbon tied prominently around his manhood.

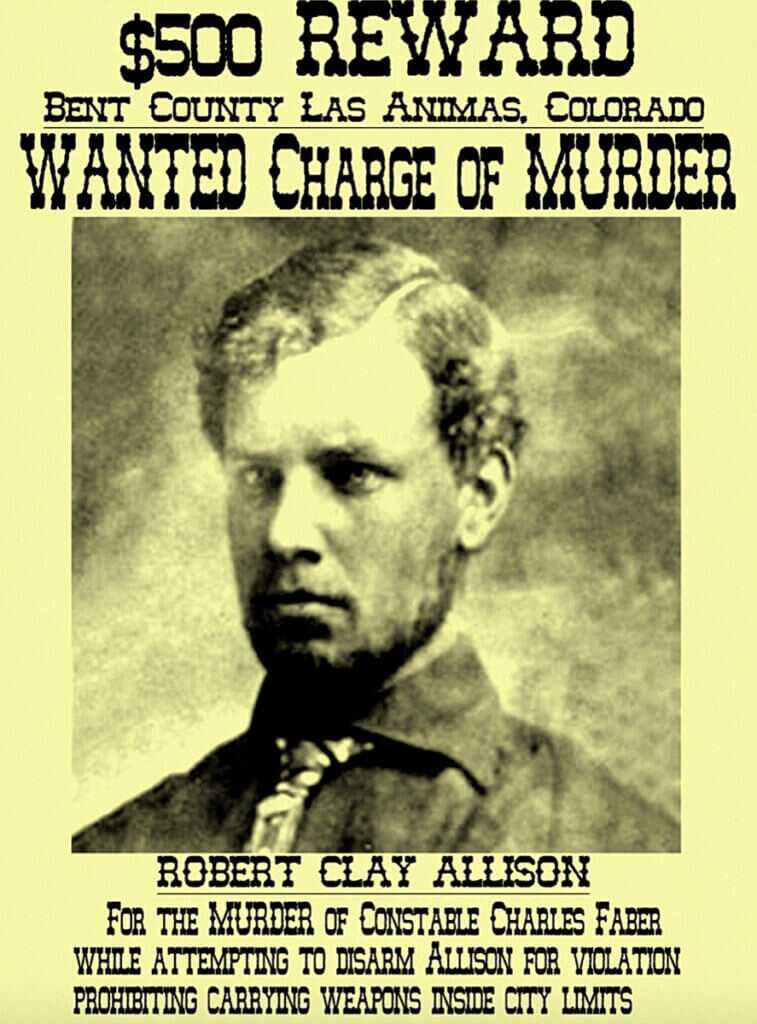

Allison also played a major role in the Colfax County War that claimed some 200 lives. In 1876 he reacted to a negative editorial in the local paper by blowing up the newspaper office with a substantial black powder charge and throwing the printing press into the nearby Cimarron River. Allison shot and killed a Deputy Sheriff named Charles Faber but later beat the rap in court. Allison was said to have faced down Wyatt Earp and Bat Masterson in Dodge City in 1878, but the details are disputed.

In 1886 Allison developed an abscessed tooth, but the dentist got nervous in the presence of such a notorious gunfighter and extracted the wrong molar. Enraged, Allison enlisted the assistance of another dentist to remove the diseased tooth before returning and pulling a molar from the first practitioner in retribution.

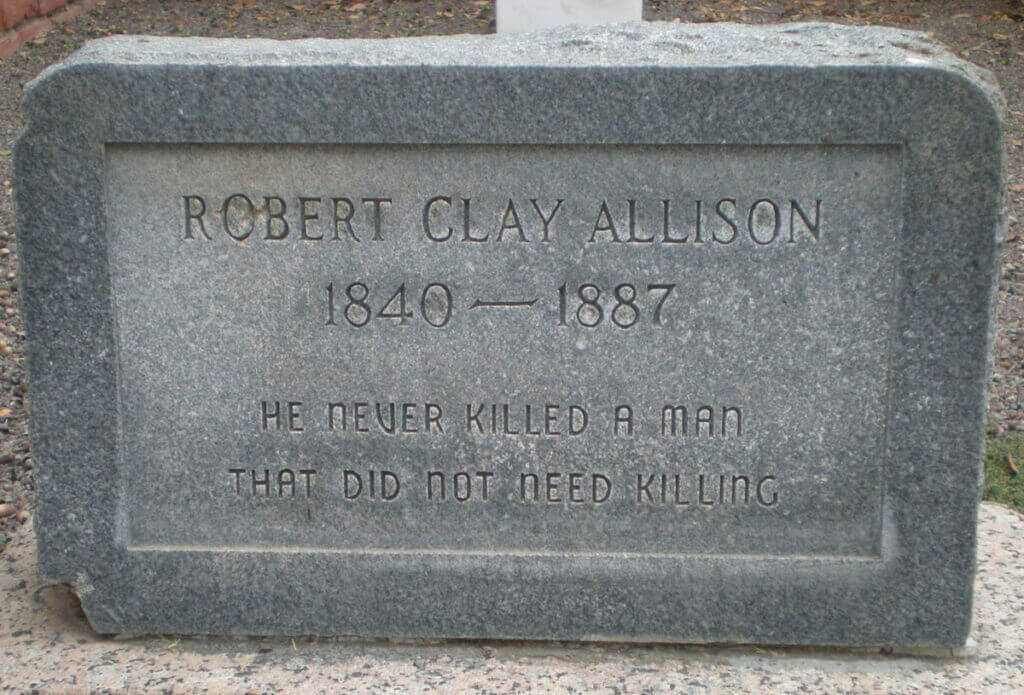

In 1887 at age 45 Clay Allison was driving a wagon loaded with supplies to his new ranch in Pecos, Texas. A grain sack shifted, and Allison lurched to prevent its falling. The inveterate gunman lost his balance and tumbled out of the wagon. The horses reared and the wagon wheel rolled across his head and neck, crushing his skull and nearly decapitating him. Clay Allison, legendary gunfighter and originator of the term “Shootist,” was laid to rest in the Pecos Cemetery the following day. A crowd of hundreds arrived to pay their respects.

|

The Colt New Service was a dominant player in the large-caliber revolver market for four decades. The New Service was loaded by swinging out the cylinder to the left and inserting six cartridges. Pushing in on the ejector rod extracted all six cases at once. Photo by Nathan Reynolds.

|

In 1888, Colt employee Carl Ehbets patented a swing-out-cylinder revolver whose cylinder was locked in position by an internal pin that engaged a depression in the center of the rotating ratchet at the rear of the cylinder.

The pin was attached to an external latch on the right side of the frame that, when pulled to the rear, disengaged the pin and allowed the cylinder to be swung out to the left where the cartridge cases were ejected by pushing on a rod that passed through the cylinder pin and was attached to a star-shaped ejector. All subsequent Colt swing-out-cylinder revolvers have been based upon that design.

The following year, the U.S. Navy adopted the new Colt revolver chambered for the .38 Long Colt cartridge, and three years later, the Army followed suit.

The new Colt .38 revolvers saw their first large-scale combat use during the Spanish-American War (1898), but during the postwar pacification campaign in the Philippines, fighting against the fanatical Muslim Moros showed the shortcomings of the .38 revolver. Juramentado suicide warriors often soaked up multiple .38 projectiles and kept on coming with their kris knives swinging. A more authoritative sidearm was needed, and as it had in the past, the Army looked to Colt.

In 1898, Colt had introduced its first large-caliber, swing-out-cylinder revolver. Called the New Service, it was an up-sized and strengthened variant of the .38 Colt revolver, and it was offered chambered for the popular big-bore revolver cartridges of the day: .38-40, .44-40, .44 Russian, .44 Special, .45 Colt, .450 Boxer (rare), .455 Webley, and .476 Enfield (rare). Options included barrel lengths of 4, 4½, 5, 5½, 6, and 7½ inches; wood or hard rubber grips; and blue or nickel finishes.

The Army purchased several thousand New Service revolvers. Known as the Model of 1909, they were chambered for a variation of the .45 Colt that used a wider rim for more positive ejection. The U.S. Marine Corps obtained a small number that had slightly different shaped grips.

In that same year, Colt improved the New Service’s mechanism, replacing a number of leaf springs with coil springs that strengthened the lockwork and reduced parts breakage. The “Colt Positive Lock” was also included in the design. It interposed a steel bar between the hammer and the frame, and that bar prevented the revolver from firing if the hammer was inadvertently released while cocking or if the revolver was dropped on its hammer.

The large-caliber Colt wheelgun proved to be popular with American outdoorsmen and law enforcement. Over the years, the .45-caliber Colt New Service was used by the New York State Police and the highway patrols of Georgia, Utah, and Montana. Michigan State troopers were issued .44-40 New Service revolvers prior to World War I.

The New Service was also popular outside the U.S. Numbers were purchased by British officers for use during the Boer War in South Africa. In 1904, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police adopted the New Service in .455 Webley, and beginning in 1919, they used .45 Colt New Service revolvers. The Cuban government purchased .45 Colt New Services before and after World War I for issue to their army and the Guardia Rurales.

With the outbreak of World War I, the British purchased .455 revolvers from Colt and S&W. As it became obvious that the United States would soon be drawn into the conflict, the Army approached S&W in 1916 about a substitute standard handgun and was offered the .45 Hand Ejector, Second Model revolver. But the Army insisted that any substitute standard handgun had to use the issue pistol cartridge, and the rimless .45 ACP would not function with the S&W revolver’s ejector system.

|

The rear sight consisted of a groove in the topstrap that was serrated to cut down on glare when sighting. |

In conjunction with the Springfield Armory, S&W developed the halfmoon clip–a semi-circular piece of flat steel with cutouts into which three rimless .45 ACP cartridges could be snapped. This allowed the rimless cases to be ejected by the extractor bearing on the clip and also facilitated very fast reloading.

When the U.S. declared war on April 2, 1917, S&W began production of the Smith & Wesson Revolver, Caliber .45, Model 1917. While the Colt factory gave priority to the production of Model 1911 pistols, it too received a contract for revolvers, and it proved to be a simple matter to modify the New Service to accept the halfmoon clips and the .45 ACP cartridge.

The result was the Colt Revolver, Caliber .45, Model 1917. Early Colt Model 1917s had their chambers bored straight through and could not fire the .45 ACP without benefit of the halfmoon clips, while later production guns had a neck in the chamber to allow them to be fired without clips in an emergency

The Colt 1917 soon appeared in hands of the Doughboys who found the big Colt a rugged, powerful handgun capable of standing up to the vile conditions of trench warfare. One notable personality who was so equipped was artillery Capt. (later President) Harry S. Truman, who in later years presented his Colt 1917 revolver and 1911 pistol to the NRA’s museum.

By 1918, Colt had delivered 151,700 Model 1917s to the government. After the war, except for a few that were retained for use by military police or distributed to National Guard units, most Colt and S&W Model 1917 revolvers were put into storage.

During the interwar years, Model 1917s were used by various federal agencies, including the Border Patrol, Post Office, Justice Department, and Treasury Department. The Army, which handled distribution, showed a definite preference for the Colt, and they accounted for the majority issued.

While the factory never used model numbers, today’s collectors recognize three versions of the New Service. The Old Model, or the first 21,000 New Services, featured a straight, untapered barrel and a rather unattractively shaped trigger guard.

After the Old Model, several thousand Transitional Models (Model of 1909) were produced with a number of mechanical improvements, including a hammer-block safety.

The Improved Model started with the Model 1917 and went to the end of production. Its slightly tapered barrel had a larger collar where it screwed into the frame and a larger, more ergonomic trigger guard.

The postwar years saw the .44 Russian, .450 Boxer, and .476 Enfield chamberings dropped and the .38 Special added. Colt’s 1933 catalog opined, “The New Service is essentially a holster revolver for the man in the open-mounted Motorcycle and State Police, the Hunter, Explorer and Pioneer. It is the Arm adopted as standard by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police and hundreds of city and state Police Organizations throughout the world.”

The year 1936 saw the New Service chambered for the powerhouse handgun cartridge of the day, the .357 Magnum. The New Service in .38 Special was popular with police and was used by the Texas Dept. of Public Safety, U.S. Border Patrol, Pennsylvania State Police, Kansas Highway Patrol, the Tennessee Valley Authority, and San Antonio and Richmond police departments. The New Hampshire State Police bought some in .357 Mag.

Colt’s 1940 catalog offered the New Service with barrel lengths of 4½ , 5½, and 7½ inches with blue or nickel finishes in .38-40, .44 Special, .44-40, .45 Colt, .45 ACP, and .455 Webley. Guns in .38 Special and .357 were offered with 4-, 5-, and 6-inch barrels. While checkered walnut grips were standard, late-production guns were fitted with plastic-like “Coltwood” grips.

|

The exposed ejector rod was a feature of most Colt revolvers until the 1970s. Photo by Nathan Reynolds.

|

With the American entry into World War II, Army warehouses were swept for weapons, and the government located 96,000 plus Model 1917 Colts that were reconditioned and issued to military police and training units. Despite wartime demands, Colt assembled a limited number of New Services from parts on hand, and according to factory figures, a total of approximately 357,000 New Service revolvers were produced by 1944.

Shooting A .38-40 Colt New Service

My brother Vincent arranged for me to borrow a New Service revolver from a friend’s collection. Chambered for the .38-40, it was in VG+ condition and featured a 4½-inch barrel and Coltwood grips. According to its serial number, it must have been one of the very last ones assembled in 1944. It had a smooth trigger pull, and unlike most handguns of that era, the sights were prominent, fast to acquire, and easy to line up.

While .38-40 ammo is hard to find nowadays, I obtained a supply of cowboy action loads from Black Hills and Ten-X. Reloading guru and fellow InterMedia Outdoors contributor Bob Shell provided me with one of his favorite loads consisting of a 170-grain JHP bullet backed by 8.5 grains of Unique.

After chronographing the three loads, I set up a D-1 target and ran the New Service through a series of offhand drills from 7 and 15 yards. Here, the big Colt came into its own, and keeping all my rounds in the center of the target was easy. The double-action trigger pull was a bit heavy, but this revolver was in NIB condition, and I believe it had been fired very little, if at all, before I ran it through its paces.

All in all, I was impressed with the New Service. While I am not a real fan of large-frame revolvers, it was reliable, comfortable to shoot, and put rounds where I wanted them to go. And when all the advertising hype is wiped away, what else do you need from a service-type handgun?

When fired from my MTM Predator rest at 50 feet, the Colt printed a bit low and to the left. Two out of the three loads put bullets close enough to where I was aiming for a fixed-sight, service-type revolver. The revolver showed a slight preference for faster bullets, and as projectile velocity increased, group sizes shrank.

After chronographing the three loads, I set up a D-1 target and ran the New Service through a series of offhand drills from 7 and 15 yards. Here, the big Colt came into its own, and keeping all my rounds in the center of the target was easy. The double-action trigger pull was a bit heavy, but this revolver was in NIB condition, and I believe it had been fired very little, if at all, before I ran it through its paces.

All in all, I was impressed with the New Service. While I am not a real fan of large-frame revolvers, it was reliable, comfortable to shoot, and put rounds where I wanted them to go. And when all the advertising hype is wiped away, what else do you need from a service-type handgun?