During the German “Spring Offensive” of 1918, the British Expeditionary Force took on part of the brunt of the German onslaught in fierce fighting that nearly pushed them back against the English Channel. The British desperately wanted U.S. troops of the American Expeditionary Force incorporated into their lines as reinforcements and met resistance from American General John Pershing.

At the beginning of the Spring Offensive, U.S. soldiers of the AEF were not available to help the allies against the German push, as they were still in training camps. This changed by summer 1918, when the first units of the AEF started trickling into France. General Pershing answered the British request for American reinforcements by sending elements of the 27th and 30th Infantry Regiments to join the British lines under British command.

The U.S. soldiers of the 27th and 30th Infantry Regiments trained with elements of the Australian and New Zealand ANZAC corps to prepare for combat in the trenches. On July 4, 1918, these American troops joined British and Commonwealth forces in the Battle of Hamel, under the command of the Australian General John Monash. During the fighting, the joined AEF and ANZAC forces contributed to a new form of combat in the Western Front, with a combined and coordinated effort of infantry pushes, air cover, artillery and intelligence that would ultimately change the nature of trench warfare.

Unlike other AEF troops on the Western Front, the men of the 27th and 30th Infantry Regiments did not use standard American arms like the M1903 Springfield and M1917 Enfield rifles. Instead, they were issued British arms and gear as they fought under British command. These arms included the Short Magazine Lee Enfield, Lewis Light Machine Gun and Vickers Heavy Machine Gun, all chambered for the rimmed .303 British cartridge.

The bolt-action Short Magazine Lee Enfield, or SMLE, rifle used by British and Commonwealth forces was one of the best service rifles used during World War I. While the standard-issue SMLE did not have the same long-range accuracy potential compared to the M1903, M1917 and German Gewehr 98, there were several features that made it better suited for the realities of fighting in trenches. The first of these notable features is its magazine capacity of 10 rounds, double the capacity of the other service rifles in use.

The SMLE was also slightly shorter than both the M1903 and M1917 rifles in use with other AEF troops, making it easier to maneuver within the tight confines of trench warfare. The cock-on-close action, in addition to the magazine capacity, of the SMLE also meant that trained soldiers could manipulate the action faster and put out a greater rate of fire compared to other bolt-action service rifles in use at the time. The SMLE uses a tangent rear sight and front sight post surrounded by large guard ears, protecting the sights from drops or falls.

Another British weapon system used by the soldiers of the 27th and 30th Infantry Regiments under British command was the Lewis Light Machine Gun, designed by a U.S. Ordnance Officer, Isaac Newton Lewis. Lewis based his design off of an earlier machine gun prototype, the McClean, which used a drum feed and gas-operated action. The Lewis Gun fed from a top-mounted rotating drum magazine containing 47 rounds, and was light enough that a single man could carry and operate it versus the more cumbersome and stationary Vickers Heavy Machine Gun.

One of the most notable features of the Lewis Gun was its finned barrel contained within a hollow shroud. Using a concept called the “Venturi” system, the barrel of the Lewis Gun ended before the opening of the shroud and the muzzle blast pushed air forward through the front while brining in cooler air through opening slits at the back of the shroud near the receiver. It was thought that this method of using flowing air and heat dissipating fins around the barrel would keep it cool during sustained fire while keeping the overall weight down in comparison to a water-cooled jacket.

The Lewis Gun also featured adjustments for the gas regulator and action spring, allowing it to be tuned as fouling built up within the system in order to keep the gun running. The demand for Lewis Guns was high throughout the war as its light weight, magazine capacity and ability to sustain fire made it a valuable asset for British soldiers fighting in the trenches. The number of Lewis Guns in use by British forces constantly grew throughout the war.

The Heavy Machine Gun Battalions of the 27th and 30th Infantry Regiments were issued the water-cooled, belt-fed British Vickers Heavy Machine Gun. The Vickers was essentially the same design as the American Maxim Gun, albeit a slightly lighter and improved version with the toggle lock turned upside-down. The Vickers uses a recoil-action operating system in which the barrel recoils backwards slightly within the water-jacket to unlock and operate the toggle action. The Vickers proved to be a reliable heavy machine gun on the Western Front, and a trained crew with plenty on ammunition, spare parts and water could fire it continuously.

By mid-1918, the tactics used by the British had improved since the disastrous first Battle of the Somme two years earlier, in which they suffered more than 60,000 casualties on the first day. The British has started off with one Vickers per battalion at the beginning of the war, which increased to several machine guns per company to support the infantry.

The number of Lewis Guns increased to two guns per platoon, or at least one per section. The British also incorporated the use of rifle grenades fired off the front of SMLE rifles as well as “bomber” troops, which were soldiers tasked with hurling multiple grenades at the enemy.

The combination of better arms and tactics being used by the British by 1918 allowed for an increased degree of fluidity to be brought back into the fighting which had previously been a near constant stalemate. This was the environment that the U.S. soldiers of the 27th and 30th Infantry Regiments under British command participated in on the old Somme battlefield in 1918. General Monash, who commanded the two American regiments, went on to say that there were “no finer troops” in regards to the U.S. soldiers fighting with the British and ANZAC forces.

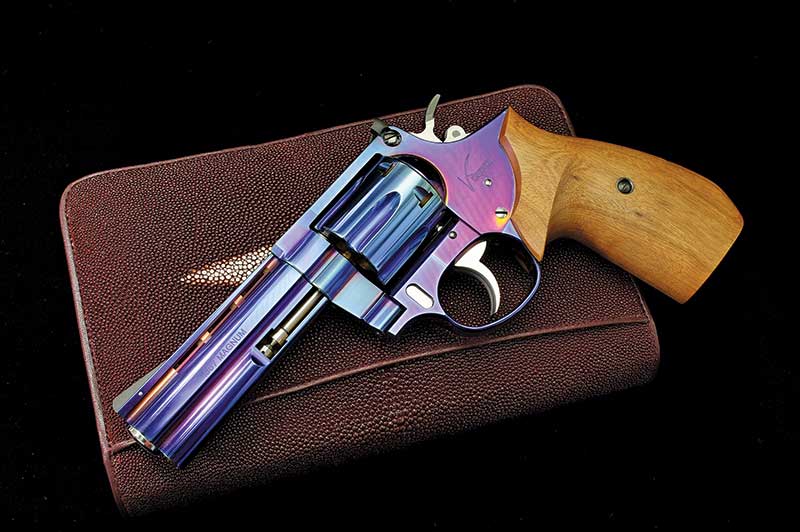

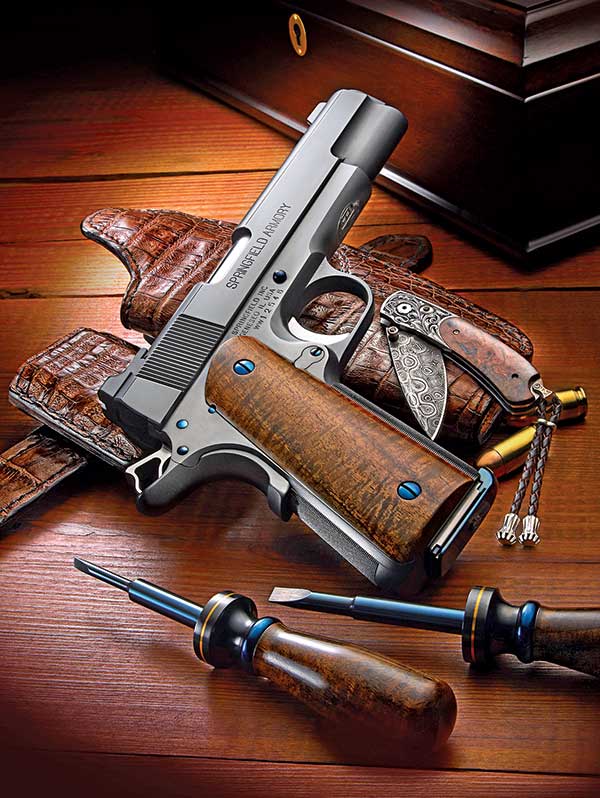

I am in lust and green with envy at the same time!

I am in lust and green with envy at the same time!.gif)

s.jpg)

.gif)

.png)

.gif)

.jpg)

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)