Month: July 2024

Holy snap! That is so not cool…

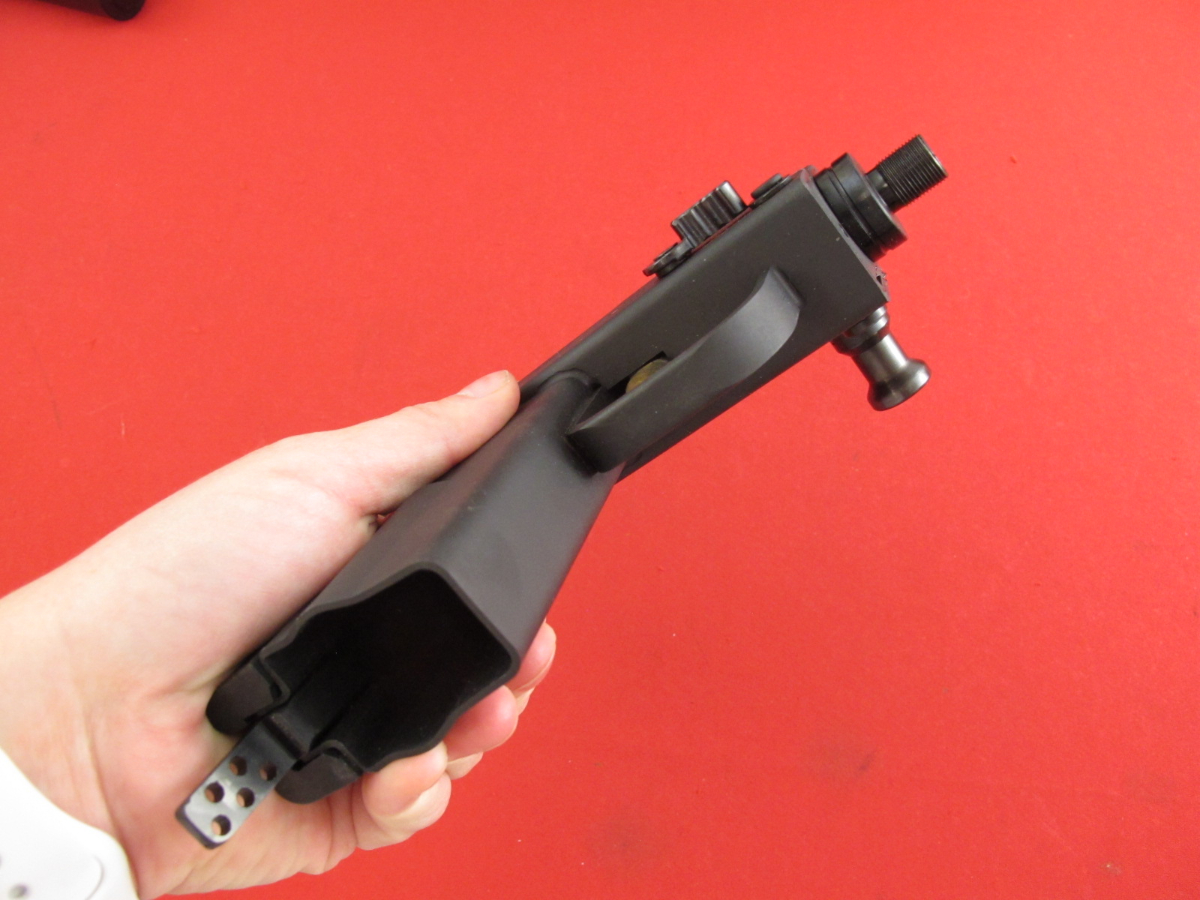

At 7:30 p.m. on 3 July 2023, North Carolina State Trooper Jeffrey Dunlap pulled to the side of Interstate 26 to assist what he assumed to be a stranded motorist. The driver, Wesley Scott Taylor, then inexplicably produced a .44 Magnum Desert Eagle handgun and shot Dunlap in the chest at near-contact range. The massive 240-grain jacketed hollow point flattened on Trooper Dunlap’s armored Kevlar vest.

Despite having been centerpunched by a .44 Magnum round, Dunlap drew his service weapon and killed Taylor in the subsequent exchange of fire. The only reason Jeffrey Dunlap, a distinguished 13-year veteran of the Highway Patrol, got to go home to his family that evening was that he was wearing superb state-of-the-art soft body armor.

- Origin Story

- Catching Attention

- A Visionary

- Kwolek Makes Kevlar

- But What Could You Actually Do With Kevlar?

- READ MORE: Biden’s Joint Speech to Congress: What do you think deer are wearing kevlar vests?

- A Vested Interest in Survival…

- READ MORE: Eberlestock Bulletproof Backpack

- The Rest of the Kevlar Story

- Things End Well For Kwolek

The National Institute of Justice (NIJ) reports that the lives of more than 3,000 Law Enforcement officers have been saved since the first issue of soft body armor began in the 1970s. That’s thousands of kids who got to keep their parents thanks to this extraordinary contrivance. Have you ever wondered where all that began?

Origin Story

Stephanie Louise Kwolek was born to Polish parents in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, in 1923. She was one of two children. Her father was a naturalist, and her mother was a seamstress. Though she was extremely close to her father, he tragically died when she was ten.

Young Stephanie and her dad spent countless hours roaming the Pennsylvania forests. Along the way, Stephanie developed a deep and abiding love for nature. Out of that grew a passion for science. Stephanie outpaced her classmates in school and resolved at a young age to become a physician.

Then, in 1946, Stephanie graduated from Carnegie Mellon University with a BS in Chemistry. This seemed a decent path to medical school. However, she took a temporary job in a chemistry lab to make money for her medical training. While there, she met Dr. William Charch who worked at DuPont Chemical. Charch is the guy who invented waterproof cellophane.

Catching Attention

Dr. Charch was impressed with the young woman’s drive and intellect and arranged for her to interview at DuPont for a position as a chemist. She got the job but never intended to stay. Throughout her early time at DuPont, Stephanie really just wanted to use her position as a springboard into medical school.

The late 1940’s was an interesting time in America. Sixteen million American men had recently served in World War 2. One in every thirty-eight died. Many large companies struggled to fill their vacancies amidst the massive economic boom that blossomed out of the war. Stephanie’s project at DuPont involved researching radical new chemical technologies. DuPont had introduced nylon recently, and their research in exotic polymers was cutting edge.

In short order, Stephanie discovered that she actually had a very real gift for chemistry and shelved her plans for medical school. WW2 had served as an engine to expand the body of scientific knowledge at an unprecedented rate. With technology exploding in the Space Age, Kwolek found herself uniquely positioned to lead that charge. Over the course of the next four decades working at DuPont, Stephanie Kwolek made some truly earth-shaking discoveries.

A Visionary

First off, the Nylon Rope Trick is a staple of modern academic chemistry research labs. I’ve done it myself a couple of times. Stephanie Kwolek first defined it. The experiment involves combining an aliphatic diamine with a solution containing aliphatic diacid chloride that is not miscible in water.

The result is a synthetic diamide that propagates as a soft film on the surface of the solution. This process is called interfacial polymerization.

By gently grasping the film and pulling it off of the solution, the resulting Nylon 66 will form a strand that can be wrapped around a stick or similar object. As the film is removed this allows the reaction between the two reagents to propagate further, creating yet more nylon. Lastly, by gently wrapping these fibers around a stick, raw nylon can be harvested.

Kwolek’s work in the 1950s and ’60s orbited around unconventional applications for exotic synthetic materials. Most of these were aramids, short for “aromatic polyamides.” The resulting fibers, in addition to being extremely tough, could be formed into a wide variety of exotic materials.

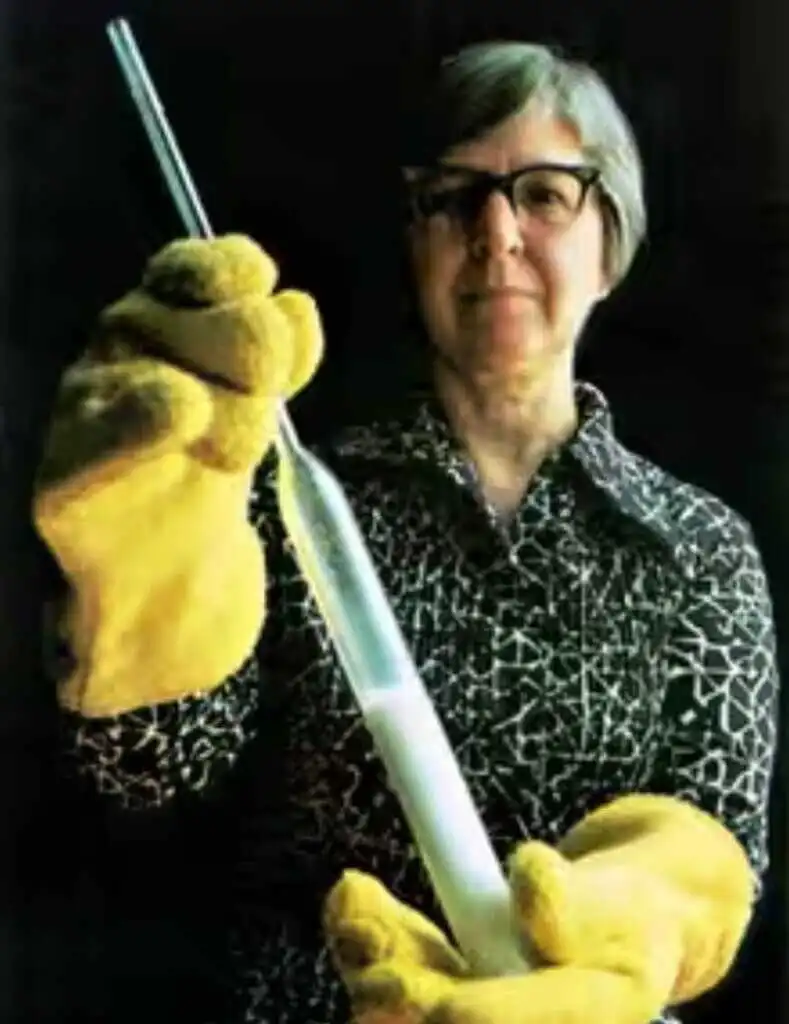

Kwolek Makes Kevlar

Kwolek’s mandate was to develop a new, tough, synthetic material that could be used in lieu of steel in reinforcing automobile tires. One of the materials she discovered was a low-viscosity, turbid, stir-opalescent liquid that looked very similar to buttermilk. This solution of poly-p-phenylene terephthalate and polybenzamide formed a liquid crystal and was typically considered a waste product.

On a whim, Kwolek persuaded Charles Smullen, the technician responsible for the spinneret machine in the DuPont lab where she worked, to let her try to extract uniform fibers from this literal garbage. Smullen, for his part, was concerned this new chemical compound would clog up his delicate machine.

Kwolek got her way and was thrilled to find that the resulting fibers were five times stronger than steel at a substantially lighter weight. She discovered that this radical new material could be made even stronger via heat treatment. Kwolek and her colleagues christened this amazing new material Kevlar.

But What Could You Actually Do With Kevlar?

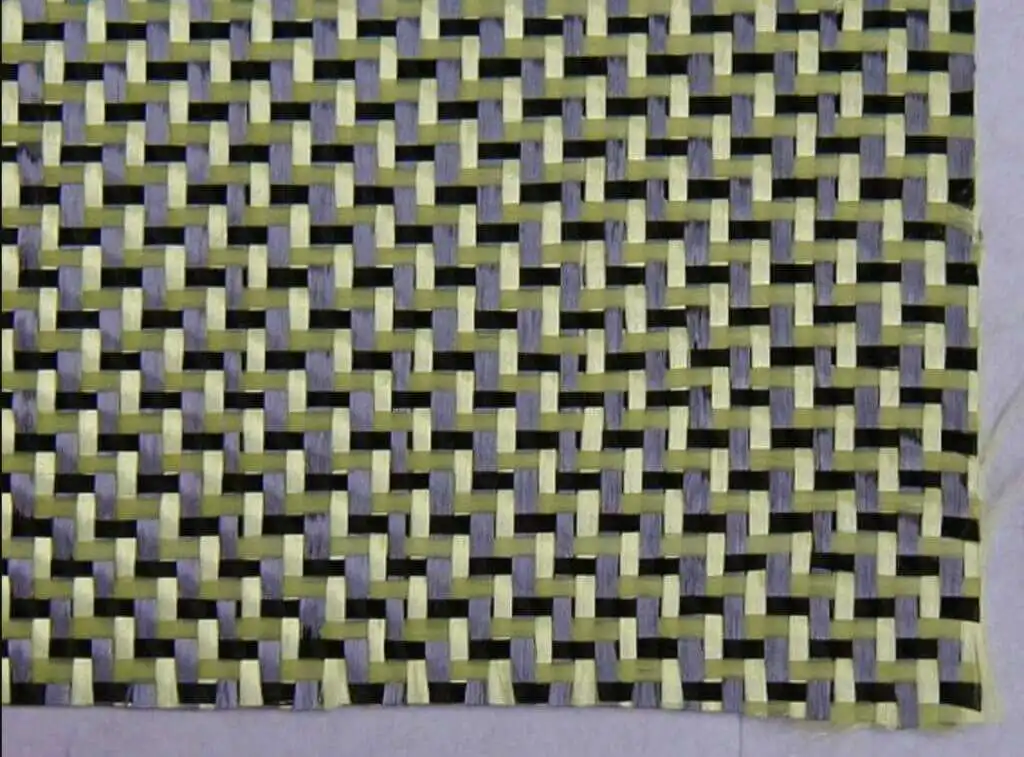

The astronomical casualty numbers that came out of World War 2 showed a desperate need for lightweight body armor that would still leave a soldier sufficiently mobile to accomplish his mission. By weaving Kevlar fibers into sheets, Kwolek found that the resulting material was durable in ways that bordered on the supernatural. Eventually, somebody tried shooting it, and the whole world moved just a little bit.

By weaving Kevlar fibers into tight sheets, engineers can produce amazingly tough materials.

The Kevlar sheets used in bullet-resistant vests are tightly woven and must be protected from the sun. Like most synthetic polymers, Kevlar degrades in direct sunlight. Stopping bullets is a function of efficient energy dissipation. In essence, when struck by a bullet Kevlar fibers will stretch without breaking.

So long as the projectile is not unduly powerful and the material is properly oriented, Kevlar did indeed reliably stop bullets, at least the handgun sort. That observation really got the juices flowing.

Ropes, cables, cell phone cases, race cars, parachute shroud lines, boats, aircraft, and space vehicles all incorporate Kevlar nowadays. The stuff is legit everywhere. By the time Kwolek died at age ninety in 2014, more than one million Kevlar vests had been produced for issue to Law Enforcement personnel.

A Vested Interest in Survival…

Modern soft body armor is divided into several frankly confusing categories. Level IIA and IIIA are expected to stop most handgun rounds such as 9mm Para, .357 Magnum, and .44 Magnum. In the case of the larger calibers, the bullet will not penetrate, but the violence implicit in surviving such a hit can still cause soft tissue injury.

All the cool kids go to war in body armor these days. Those codpieces, while critically important, always look just a wee bit comical.

Level III and IV body armor is rated to stop large-bore, high-velocity projectiles from long guns. As the degree of protection increases, however, the vests typically get heavier and bulkier. When the threat simply becomes too threatening, most soldiers in the Armies of advanced nations as well as tactical teams will use plate armor that is made from either alloyed steel or advanced ceramic materials. Plate armor will reliably stop all but the nastiest armor-piercing rifle rounds.

The Rest of the Kevlar Story

At the time of her death, Stephanie Kwolek held 28 patents. In addition to Kevlar, she was also instrumental in the development of both Nomex and Spandex.

In so doing, Kwolek likely did more to extinguish flaming aviators and support sagging body parts than any scientist before or since. Kwolek’s exotic new materials have become commonplace around the globe.

Because she worked for DuPont, Kwolek relinquished the rights to materials discovered on company time to her employer. As a result, despite the fact that the resulting monetization of her ideas brought in literally billions of dollars, Kwolek herself benefitted minimally from her groundbreaking discoveries. According to Google, her net worth was around $5 million at the time of her death.

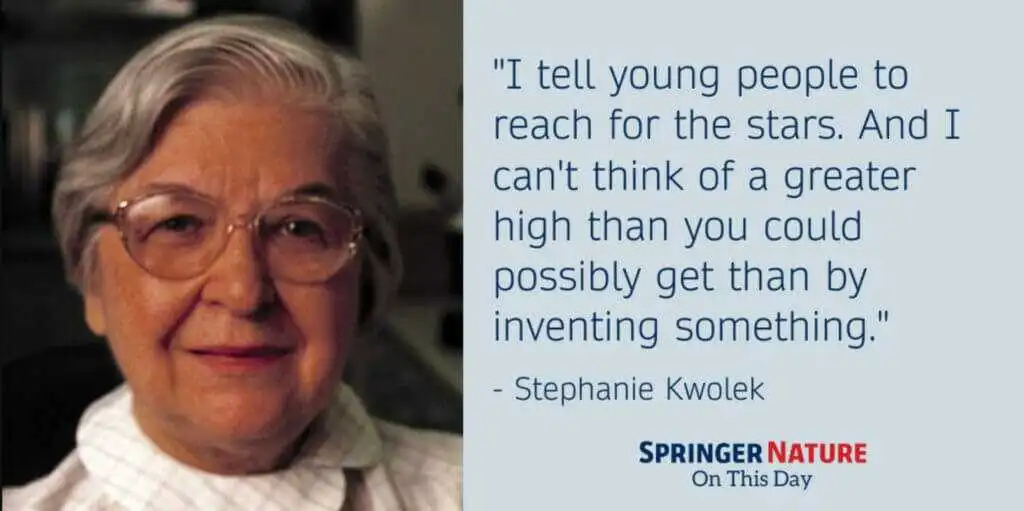

Things End Well For Kwolek

Despite her relatively modest financial success, Kwolek was honored with a wide variety of personal and professional awards. She was ultimately granted a further three honorary degrees as well. By all accounts, she led an exceptionally satisfying life. Here are a few quotes—

“I guess that’s just the life of an inventor: what people do with your ideas takes you totally by surprise.”

“I hope I’m saving lives. There are very few people in their careers that have the opportunity to do something to benefit mankind.”

“Not long ago, I got to meet some troopers whose lives had been saved. They came with their wives, their children, and their parents. It was a very moving occasion.”

The extraordinary female inventor Stephanie Kwolek clearly found ample satisfaction with her life’s work. Whether it was flame-retardant clothing for military aviators, bullet-resistant vests that have ultimately saved countless cops, or push-up brassieres and bikini swimsuits, Kwolek’s inventions have legitimately changed the world.

It was obviously a pretty great thing that she never followed through on her plans for medical school.

A decade after the Model 1851, Colt brought out a streamlined version.

Both were mostly just called Colt’s Navy revolvers.

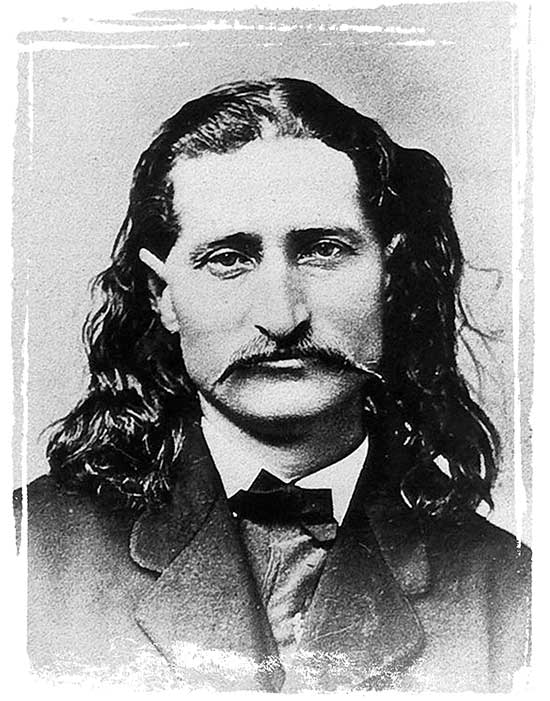

The most famous gunfighter who favored the Colt Navy (actually a brace of matched ones) was James Butler Hickok.

The era of The American gunfighter of fact and legend didn’t begin until 1850. That was when Samuel Colt introduced his first “Belt Pistol” meaning one practical for a man to actually wear on his person in a holster. Prior to that, Colt revolvers came in two types; the big military .44s weighing over four pounds and meant for packing in saddle holsters, or small .31-caliber “pocket pistols” intended for civilian self-defense and concealed carry. Consider this: before about 1850 one of the most famous Old West figures was Jim Bowie, the famous knife fighter. After that time most famous Old West personages were gunfighters.

Today, commonly called Model 1851 Navy, Sam Colt’s belt pistol actually appeared the year before. Its frame was a new medium-sized one. Its .36 caliber was between the .31 and .44 sizes, previously offered by Colt. Worthy of note is in the era of percussion revolvers caliber was denoted by the barrel’s bore size and not its groove diameter. Hence the new Colt was termed .36 caliber when the proper ball size for it was actually .375″.

The “Navy” term didn’t come because the US Navy adopted the model; it came because the roll-engraved scene on its cylinder depicted a naval battle. The scene showed a battle that took place in the Gulf of Mexico on May 16, 1843, between ships of the navies of the Republic of Texas and Mexico. The “Navy” term became so synonymous with the belt pistol it became commonly called “Colt’s Navy” and .36 was often simply referred to as “Navy caliber.”

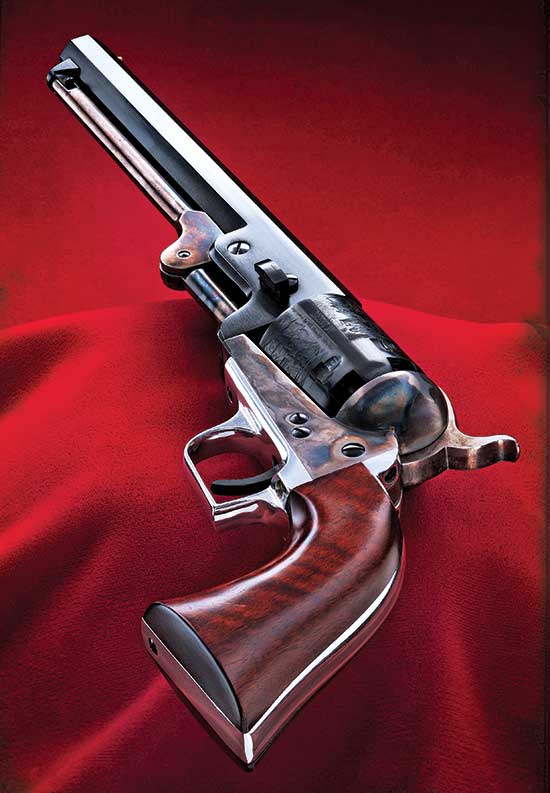

Sam Colt gladly accepted custom orders so original belt pistols can be found in a wide variety of finishes and barrel lengths. Yet the quintessential Navy Colt had a 7½” octagonal barrel, blued barrel and cylinder, color case-hardened frame, hammer and loading lever and a grip frame of nickel-plated brass. Grips were 1-piece wood, but many Navy Colts wore custom ivory grips.

Early ones had a square back triggerguard. Shortly into production, that was changed to a roomier oval type. Weight was only about 2½ pounds, making it perfectly feasible to wear on a belt and quickly accessible when needed. Of course, the mode of fire was single-action-only.

Modern manufacturers — like this Uberti — make very nice reproduction 1851s. Photo: Jonathan Armand

Pure lead round balls were the most common projectile used in Colt’s revolvers. From left to right they are .31 caliber, .36 caliber and .44 caliber. Pure lead balls for .36 caliber were .375″ in diameter and weighed about 80 grains.

The Colt Model 1851s didn’t get the Navy nickname because of an adoption by naval forces. It came from the naval scene roll-engraved on the cylinder.

This powder flask is marked for the Colt Navy and its spout is adjustable for the proper black powder charges for both conical bullets and round balls.

About the best Duke could do with his 2nd Generation Colt Model

1851 was 4″ to 5″ groups like this at 25 yards.

Stopping Power?

Until the advent of the Colt Navy, personal altercations were settled with knives. The victor was usually the strongest and largest antagonist. Sam Colt helped equal the odds because then quarrelers could stand apart and shoot it out. Large size only made for a bigger target. Reflexes and gun handling ability counted more, with of course eyesight being a factor too. Colt percussion revolvers of all types wore the most basic of sighting equipment though — a notch in the hammer with a bare nub of a front sight.

By today’s standards Navy Colts had rather puny “knock-down” power. Projectiles for them came in two forms, either a round ball or conical bullet, weighing about 80 and 140 grains respectively. From a 7½” barrel, black powder propelled them at about 1,000 fps for the ball and 750 for the bullet.

In terms of foot-pounds of energy (not that it matters) they landed roughly between modern .32 and .380 autos, which is about the right way to think of the .36. Think of firing an 85-grain .380 at around 900 to 1,000 fps and you’ll get an idea of what a Colt Navy had on-board.

However, only pure lead was used for bullet alloy so wounds were often severe, especially if bones were hit. Furthermore, balls often lodged in a victim’s bodies causing complications such as infection. It has been written that famous outlaw Jesse James took a .36-caliber ball to his body as a guerilla fighter during the Civil War and carried it until his death in 1882.

Although the Colt firm sold “cartridges” — paper ones holding a black powder charge and one of the two types of projectile — they also sold powder flasks and bullet moulds. Powder flasks wore spouts made to measure out the amount of black powder fitting into the 1851’s chambers, leaving enough room to seat the ball or bullet on top.

It was also a good idea to seal the top of the chamber with some sort of soft grease. That kept moisture out and also helped stop flashover, which was when flame from the shot being fired leaked into adjacent chambers so that all let go simultaneously. It happened in the old days, and still happens today with this sort of revolver if you’re not careful.

As a final step the percussion cap goes on the chambers’ nipples, making the revolver ready to fire. Back in the era when men carried percussion handguns into all sorts of weather they sometimes dripped candle wax over the percussion caps so they were sealed from moisture.

Speaking of weather, in the beginning of the pistol-packing era, the most common holster was the military flap type with a piece of leather covering the top of the handgun to protect it from rain, snow, mud, hard knocks and debris. When gunfighting became a factor, pistol-packers cut away the flap so as to make the revolver more accessible.

While all this was evolving, so was the California gold rush of the 1850s. Even today, “boom towns” are rough places so carrying revolvers in California mining camps became standard adornment. Those were mostly Navy Colts with 7½” barrels so their holsters were long and slender. Today those holsters are known as Slim Jim or California holsters.

Sold as a Colt accouterment, bullet moulds were brass and cut

for both round balls and conical bullets.

During the 1850s, especially in California during the great gold rush,

Colt Navy Model 1851s were holster-carried. Also needed for reloading

were a powder flask, caps and a pouch for lead balls and perhaps a

small screwdriver/nipple wrench.

Sam Colt felt a small notch in the hammer was sufficient for a rear sight on his early revolvers.

The front sight on the Model 1851 Navy was a tiny brass stud set into the barrel. This sight setup didn’t seem to faze gunfighters like Wild Bill Hickok.

There’s a common misconception that whenever a new development was introduced in handguns in the mid-1800s, gunfighter types jumped right on them. For example when Colt’s 1860 Army .44 appeared you might think gun-toters discarded their Navy Colts for the bigger caliber. Some may have, but the .36s stayed popular. They were lighter and didn’t have the exaggerated grip frame of the newer design.

The same reason people carry small autos or revolvers today — because they’re handy, not necessarily because they’re very effective. Besides, immediately after the Model 1860’s advent, Civil War demands took most of the Colt factory’s production. As late as the 1870s, some dedicated gunmen preferred their Colt Navy sixguns even after metallic cartridge handguns were for sale.

Perhaps the most famous of those was Wild Bill Hickok who used his brace of Colt Navy .36s when serving as city marshal for Hays, Kan. in the early 1870s. Wild Bill became the most famous “pistolero” of his era and will forever be identified with Colt’s Navy revolver because he was photographed with a brace of fancy, ivory-stocked ones.

During its 22 years of manufacture about a quarter million Colt Navy revolvers were made, both at the company’s Hartford factory and at a short-lived London plant. Today Model 1851s are either very valuable or in pitiful condition. I’m not going to shoot either type. However, in the 1970s and spilling over briefly into the 1980s, Colt Firearms once again offered Model 1851s made of new steels and usually exhibiting quite good workmanship. There are many rumors of exactly who made these guns but that doesn’t concern us here.

Colt Model 1851 was commonly sold as cased sets with accessories

such as powder flask and bullet moulds.

Original holsters for Colt Navy .36s were full flap military types.

Civilians often just whittled the flap away.

A Cased Set

I just happen to have a brand new unfired sample of that newer Colt series in a cased set, with powder flask and bullet mould, and it’s a wonderful looking kit. Originals were often sold in just such sets. To start with, bullets were cast in the little brass mould that came with the set.

It was cut for both round ball and conical bullet. Molten pure lead was ladled into it, and brothers and sisters I can assure you gloves will be needed with that thing. Only a few pours were made before it got hot, and by the time 60 projectiles were made (30 of each style) I couldn’t hold onto it any longer — even with heavy leatherwork gloves. I can’t imagine Wild Bill casting his own .36 Navy lead balls on some fair damsel’s cook stove.

The powder flask in my cased set is labeled “Colt Navy.” The spout has two settings: one for the longer conical bullets and one for round balls. That latter setting dropped 24 grains of Swiss FFFg black powder. Swiss brand was chosen because it’s the hottest on today’s market. That much powder just allowed the pure lead balls to seat below flush in the chambers. After all six were powdered and balled some lard was spread atop each. Then the percussion caps were seated and the revolver was ready for firing.

Let me add this, my 60-plus-year-old fingers are getting slightly arthritic; all the small motor skills needed to load that thing are far more difficult now than when I got my first cap-and-ball sixgun in 1967! Something else changed are my eyes. The sights on the Navy Colt were just a blur, so the 5-shot groups fired at 25 yards were all 4″ to 5″ in size. My 1851 was centered for windage but impacted about a foot above point-of-aim. That meant it was about “on” at 100 yards. In fact I did manage to hit an Action Target’s PT Torso steel plate twice out of a cylinder-full at that range. The chronograph said the 80-grain balls were going 974 fps on average.

Many handguns favored by fighting men came later: Colt SAAs and New Services, S&W N-frame .44s, the .357 Magnum and perhaps the top dog of all, the many 1911 .45s. But the gunfighter’s beginning was with Colt’s 1851 Navy .36.

In 1905, Smith & Wesson was riding high on its Hand Ejector Series of double-action revolvers featuring a swing-out cylinder, 10 years before the Hand Ejector had been perfected to the point of starting to manufacture these revolvers on the I- (.32 cal.) and K- (.38 cal.) frames. However, plans for a new large .44-cal. frame were coming along.

The first cartridge for this new frame would be an updated version of the .44 Russian round. Smith & Wesson’s engineers lengthened the case by .360″ and added 3 grains of black powder to a 246-gr. round-nose bullet yielding a muzzle velocity of 755 fps from a 6″ barrel. The new cartridge was christened the .44 Smith & Wesson Special. Smith’s new revolver would be called the .44 Hand Ejector First Model.

So concerned was S&W about holding the new revolver together to withstand the rigors of the new and powerful cartridge, that they added a third locking point to the cylinder. Heretofore, Hand Ejectors locked at the rear of the cylinder via an extension of the ejector rod into a hole in the recoil shield, and the other end locked into a spring-loaded pin mounted on a lug on the barrel.

The third locking point was a lug on the yoke that mated into a recess machined into the frame. This third lug was drilled with a hole to accommodate the ejector rod. Shooters would soon deem this model the Triple Lock. Production of the Hand Ejector First Model began in 1907. This was the first Smith & Wesson revolver with an under lug on the barrel shrouding and protecting ejector rod.

It wasn’t until the following year that the new revolver became available. The revolvers were available in either blue or nickel finish, and sights were either fixed or adjustable (target). Barrel lengths were 5″ or 6 1/2″, though a few were made with 4″ barrels. An extremely limited number of these revolvers were produced in .38-40, .44-40 and .45 Colt, as well. The price was $21. Oddly enough the Hand Ejector First Model did not set the world afire. Sales languished at about 2,000 per year.

In a cost-cutting move, S&W decided to jettison the ejector shroud and third locking lug and reduce the price from $21 to $19. This would be known as the .44 Hand Ejector Second Model and was produced from 1915 until October 1917, due to a demand for large-frame revolvers to support World War I efforts. The factory resumed production of the Hand Ejector Second Model in 1920 and ran until 1940 when the needs of war superseded the civilian market.

It was during this period that a group of aficionados calling themselves the 44 Associates developed. Led by a sawed-off cowboy from Montana, one Elmer Keith, this group learned that by handloading, the .44 Spl. could perform much better than the factory loads of the day. Keith, along with his friend Harold Croft, developed a semi-wadcutter design of cast bullets that performed better than anything of the day for self-defense, as well as hunting. Belding and Mull made the molds to Keith and Croft’s specifications, and they, along with their fellow 44 Associates turned a bunch of hobbyists into a near cult of handgun hunters. Their work would eventually lead to the .44 Rem. Mag. cartridge, but that’s getting ahead of us.

Early on during the production of the Hand Ejector Second Model, a number of customers called for S&W to bring back the shrouded ejector rod. The company at first resisted the change feeling that it wasn’t much of a seller the first time around, and it was expensive to produce. A company in Fort Worth, Texas, Wolf & Klar, placed an order for 3,500 Second Models with a shrouded extractor rod. Harold Wesson was leading the company co-founded by his grandfather in 1926, and he ordered that the shrouded extractor rod be produced.

This became known as the Hand Ejector Third Model or sometimes the Model 1926. The Third Model was a special-order-only revolver and was not cataloged until after 1940. Post-war civilian production found most of the Third Models being made from parts on hand. Sales were a little lackluster, so the company decided to pursue a modernization of its line.

Such features included an integral rib along the top of the barrel, a shorter throw on the hammer—a.k.a. short-action—and a new micrometer-style adjustable sight. This revolver was called the Hand Ejector Fourth Model or Model 1950 Target Model. Initial sales were dismal—a mere 244 copies were sold during its first three years of production. It recoiled too much for the target shooters of the day, and with a 6 1/2″ barrel it was quite a burden for most law enforcement officers.

The only thing that saved the Model 1950 was Elmer Keith and his incessant ranting about his heavy .44 field loads. The .44 Mag. was introduced in 1956, thus putting another nail into the Model 1950’s coffin. In 1957 the model number system took over Smith & Wesson’s product line and the Model 1950 became known as the Model 24. It limped along until 1966 when the Model 24 was dropped from the line.

During its sputtering run, the Model 1950 or 24 had some limited, special-order runs with 4″ and 5″ barrels. But the overshadowing of the .44 Mag. kept these versions checked in terms of sales. A few smart guys glommed onto them, and today a factory 4″ or 5″ .44 Spl. has a lofty premium to its already stratospheric price.

Along came the 1970s, and a gun writer out of New Mexico, along with a few other ne’er-do-well cohorts began touting the virtues of the .44 Spl. cartridge and the Model 24 revolver. Skeeter Skelton was one of those handgun enthusiasts who was smart enough to latch onto a 4-incher. Skelton touted the accuracy and controllability of handloaded .44 Spl. cartridges in a lighter, easier-to-pack revolver than the .44 Mag.

His articles were often spiced up with vignettes of adventure from his law enforcement background—Skeeter was a great storyteller—prompting a lot of handgun enthusiasts, including me, to scrounge about any purveyor of guns for a Model 24 Smith & Wesson. On those rare occasions when one surfaced, the price was usually about 50 percent more than the already outrageous scalper prices for .44 Magnums at that time.

So scarce was the Model 24 that a lot of us, again including me, resorted to getting another N-frame Smith converted to .44 Spl. by a cadre of pistolsmiths. In 1976 I bought a brand new Model 28 Highway Patrolman and with an original 6 1/2″ 1950 Target barrel had it re-chambered and fitted. While my pistolsmith was at it, I had him shorten the barrel to 5″, as I like the balance of that barrel length. It remains in my modest stash of guns and is one of my most accurate revolvers.

Smith & Wesson—like most gun makers—may be a bit slow to recognize a trend, but it again reintroduced the Model 24 in 1983 with a limited run of 2,625 revolvers with 4″ barrels and 4,875 with 6 1/2-inchers. These are designated as the Model 24-3. Lew Horton, the Massachusetts distributor commissioned a special run of Model 24s with 3″ barrels and a K-frame-sized round butt. I snagged one of them right away when I worked in a Wyoming gun shop.

Later I bought an unfired 4-incher from a collector. Today any of these Model 24-3 revolvers command a premium north of $1,100. Smith & Wesson has done some additional limited runs, deemed the Model 24 Classic, but they are all 6 1/2-inchers. A Model 624 has also been produced having all the features of the Model 24-3 revolvers, but made of stainless steel.

Smith & Wesson has been tortured with competing business parameters. During its revolver heydays of the 1950s, ’60s and ’70s, the .44 Mag.—renamed the Model 29 and later the stainless steel Model 629—easily outsold its little brother. The American “bigger is always better” mindset kept the production line full of the magnum revolvers. Nonetheless, a cadre of revolver sophisticates kept relentless pressure on the company to maintain the Model 24 in its line.

Yet nearly every time it produces a run of the Model 24 it just barely sells out, and the excitement wanes a while. Today, the company can’t seem to produce enough semi-automatic pistols, even while revolver zealots pine for their favorites. Decisions…decisions…