The attack on Bari harbor in Italy in 1943 was a debacle of epic proportions

for the Allies. However, great good was ultimately to come from this dark day.

December 2, 1943, was a Thursday. Allied troops worked feverishly in the freshly-liberated Italian port of Bari on the heel of Italy, offloading the ammunition and supplies required to support the ongoing fight against the Axis. Italy had capitulated three months before, but the Germans still fought like lions.

The port was fat with ships from America, England, Poland, Norway, and the Netherlands. On this very Thursday, British Air Marshal Sir Arthur Coningham, commander of the Allied Northwest African Tactical Air Force, stated, “I would consider it as a personal insult if the enemy should send so much as one plane over the city.” He would live to regret that.

The Germans attacked with 105 Ju-88 A-4 bombers from Luftflotte 2 and achieved complete surprise. The raid spanned about an hour. The attacking Luftwaffe raiders sank 27 cargo ships in the harbor. More than 1,000 allied troops, sailors, and merchant seamen perished alongside roughly the same number of civilians. The Germans lost but a single plane.

That would be bad enough, but survivors pulled from the oily water also began to manifest horrific skin burns. Massive blisters formed on their flesh. Six hundred twenty-eight military patients were hospitalized, suffering from these ghastly injuries. Eighty-three of them eventually died.

At first, there was a suspicion that the Germans had attacked the harbor with chemical weapons. However, the truth was something potentially far worse. The details were immediately suppressed, but we had just inadvertently exposed our own troops to mustard gas.

Among the 27 sunken vessels was a Liberty ship called the SS John Harvey. Its top secret cargo included 2,000 M47A1 mustard bombs to be used in the event Hitler first employed chemical warfare agents on the European battlefields.

During the Luftwaffe attack, these diabolical weapons had broken open, and the mustard agent had mixed with the fuel oil spilled into the harbor’s waters. The results were predictably horrifying.

Adolf Hitler was likely among the top five worst people who ever lived, and the experience he had with chemical agents during World War I kept him from using these dreadful things in World War II.

In the face of such an epic tragedy, Lieutenant Colonel Stewart Francis Alexander, a chemical warfare specialist on Eisenhower’s staff, was sent to Bari to investigate. He immediately identified mustard gas exposure. Alexander’s “Final Report of the Bari Mustard Casualties” was predictably classified.

Lt. Col. Alexander’s superior officer at the Chemical Warfare Service (CWS) was Colonel Cornelius P. “Dusty” Rhoads. This was a citizen Army drawn up for the global conflict, and these guys came from all walks. In his previous life, Dr. Rhoads had served as head of the Treatment of Cancer and Allied Diseases Department at New York’s Memorial Hospital.

Col. Rhoads had an unprecedented opportunity to study hundreds of victims of mustard poisoning. He observed that the mustard agent suppressed cell division. Using his experience in oncology as a basis, it occurred to him that mustard agent might be used to inhibit the rapidly reproducing malignant cells that drive cancer.

Every day the human body creates around 330 billion new cells. Almost all of these cells demand that the entire genome be reproduced. Each of these packets of genetic information includes around 3.2 billion base pairs. Given that astronomical volume, mistakes are inevitable.

God designed us with proofreading mechanisms that catch most of these mistakes and destroy the aberrant cells before they can do any damage via a process called apoptosis. However, if one of these cells is almost but not quite normal, it can slip through that net and morph into cancer. These cancer cells typically multiply faster than normal cells and in an uncontrolled fashion.

Col. Rhoads became convinced that the active ingredient in mustard gas could be used, in very small doses, to attack rapidly-metabolizing cancer cells.

After the war, he approached Alfred Sloane and Charles Kettering to fund the Sloan Kettering Institute for Cancer Research (SKI). These two men had made fortunes off of war production through General Motors. The resulting cutting-edge research facility was manned by scientists no longer needed for the advancement of war goals. They proceeded to synthesize mustard derivatives into the first effective medications for cancer. Nowadays, we call this chemotherapy.

In 1949, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved Mustargen (mechlorethamine) as the first experimental chemotherapy drug in America. It was used to successfully treat non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. This effort planted a seed that became the flourishing field of oncology today.

Thanks to this serendipitous discovery and a lot of hard work, cancer is no longer the death sentence it once was. Today, chemotherapy agents specifically target rapidly-metabolizing malignant cells while selectively sparing the healthy stuff, but there is still some overlap. That’s why many patients undergoing chemotherapy lose their hair because hair cells metabolize quickly as well.

The attack on the Bari harbor in 1942 cost some 2,000 lives. However, the American Cancer Society has since described the Bari attack as the beginning of “The Age of Cancer Chemotherapy.” Millions of people have had their lives saved or extended due to research that spawned from that terribly dark day.

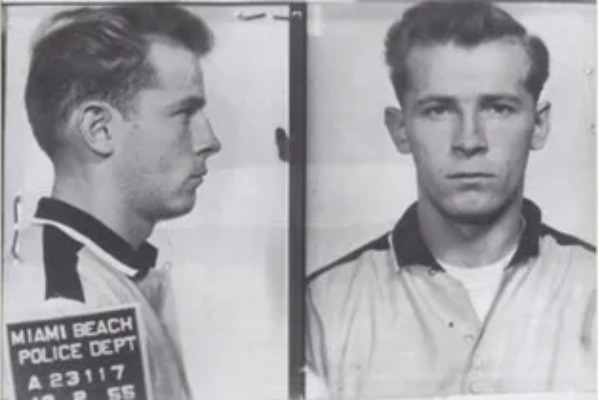

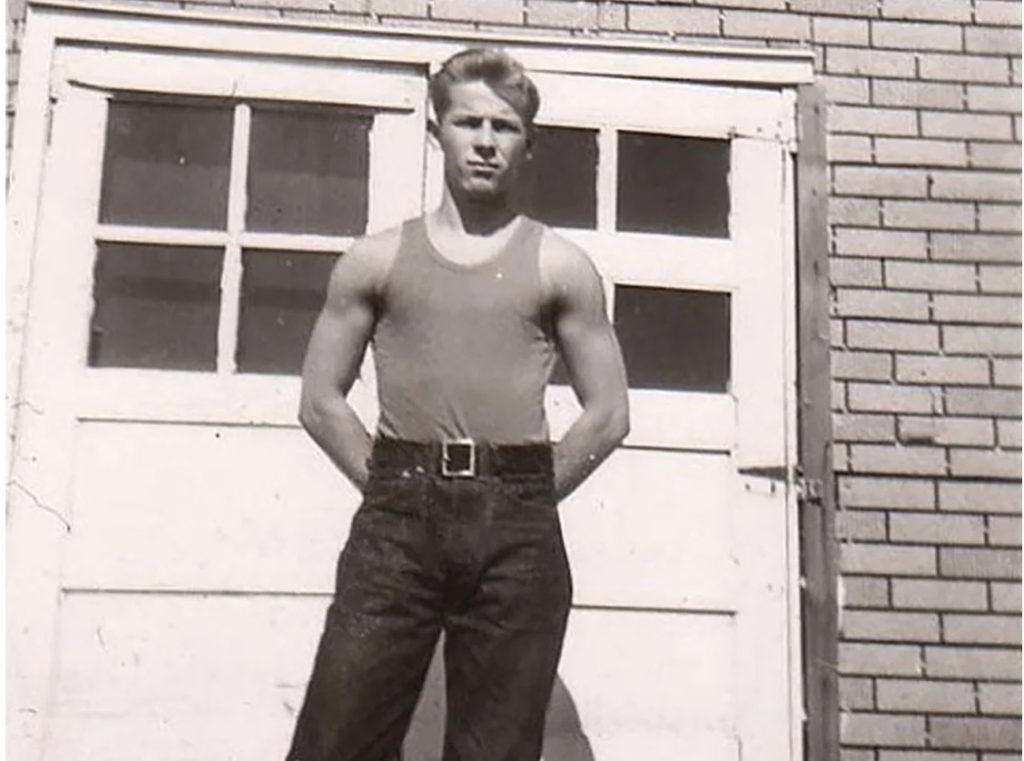

James Joseph Bulger, Jr was born September 3, 1929, to James Joseph and Jane Veronica “Jean” Bulger. He was their first of three children. His father hailed from Newfoundland. The senior Bulger’s parents had both been Irish. Jean was a first-generation Irish immigrant. The younger Bulger’s blood ran green.

James Senior worked as a longshoreman but lost his arm in an industrial accident. There were not quite so many lawyers back then as is the case today. Though the man survived, his family was left destitute. They moved into the Mary Ellen McCormack housing project in South Boston in 1938.

James had two younger brothers, both of whom did well in school. By contrast, James Bulger Jr seemed drawn to the streets at a young age. The kid was a born thug.

To his friends, James went by “Jim”, “Jimmy”, or “Boots.” The latter appellation stemmed from his tendency to wear cowboy boots in which he hid his switchblade knife. When he was young the kid’s hair was blonde to the point of being white. As a result, his chums took to calling him “Whitey.” Though the young man despised the nickname, it nonetheless stuck.

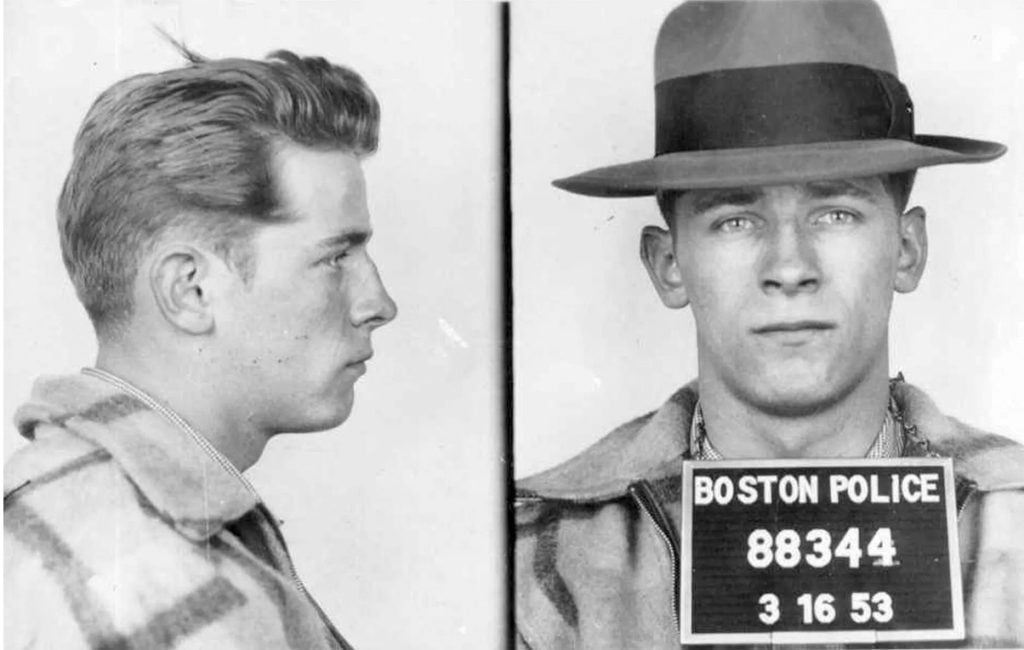

Whitey Bulger’s first arrest was at age 14 for larceny. He ran with a South Boston street gang called the Shamrocks. While with this crew Bulger was eventually arrested for assault, forgery, and armed robbery. He spent time in the juvenile reformatory, but everybody wants kids to succeed. Soon after his release in 1948, Whitey was allowed to join the US Air Force in hopes that a little time in uniform might straighten him out.

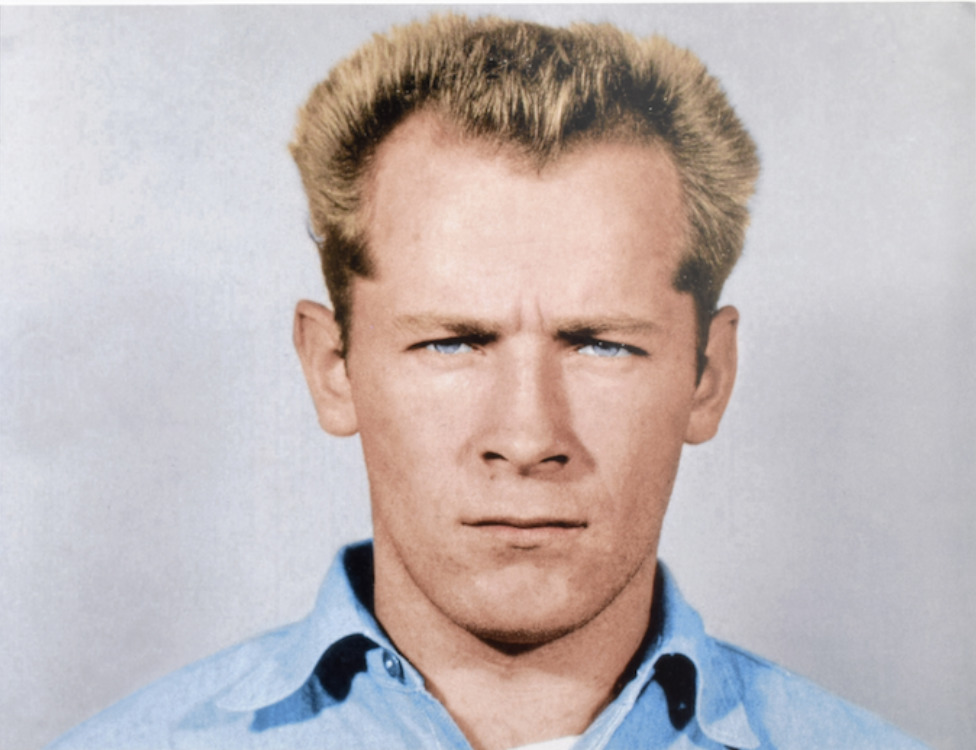

Airman Bulger did not thrive in the service. He spent time in a military prison for multiple assaults and also went AWOL. By 1952 Uncle Sam had given up on Whitey and sent him packing, albeit with an honorable discharge. Four years later Bulger was remanded to federal prison for armed robbery and hijacking. Apparently, the kid just couldn’t help it.

As we mentioned earlier, this was a different time with very different rules. While serving time in prison Bulger was used as a test subject for the CIA’s Project MK-ULTRA. This enterprise was pitched as an effort to cure schizophrenia. In reality, the CIA was trying to develop a mind control drug.

While Bulger and the eighteen other participants in the program had indeed volunteered in exchange for reduced sentences, they had no idea of the true nature of the program. They received heavy doses of LSD along with several other hallucinogens. Bulger later admitted that the experience was horrifying. He began hearing voices afterward as a result.

Bulger was later transferred from Atlanta to Alcatraz and then on to Leavenworth. In 1963 he was sent to Lewisburg Federal Penitentiary. On his third try, Whitey Bulger was paroled in 1965. He had served a total of nine years. The career criminal would not see the inside of a prison again for another nearly half-century. However, that wasn’t for lack of trying.

As an ex-con, solid work was tough to find. Bulger toiled as a janitor and construction worker before returning to the only thing he had ever been good at. Under a mob boss named Donald Killeen, Whitey Bulger began working as a loan shark and bookmaker. The Killeen Gang had been a fixture in South Boston for more than two decades.

The Killeen Gang was led by three brothers—Donnie, Eddie, and Kenny. Kenny Killeen purportedly shot and injured Michael “Mickey” Dwyer, a player in the rival Mullen Gang, during a fight at the café the Killeens used as a headquarters.

There resulted a sprawling gang war that swept across Boston stacking up quite the body count. The Killeens soon found themselves outgunned by the younger, more agile Mullens mob. As part of this fight, Whitey was dispatched to liquidate a Mullens Gang member named Paul McGonagle. In a tragic case of mistaken identity, Whitey accidentally killed Paul’s fraternal twin brother Donald. This was Whitey Bulger’s first proper murder. It would not be his last.

One of the players named Kevin Weeks later said, “Although [McGonagle] never did anything, he kept on stirring everything up with his mouth. So (Whitey) decided to kill him…(Whitey) shot him right between the eyes. Only…it wasn’t Paulie. It was Donald…(Whitey) drove straight to his mentor Billy O’Sullivan’s house (who was cooking at the stove top at the time)…and told O’Sullivan…’I shot the wrong one. I shot Donald.’ Billy…said, ‘Don’t worry about it. He wasn’t healthy anyway. He smoked. He would have gotten lung cancer. How do you want your pork chops?”

Sensing that time was running out on the Killeens, Bulger supposedly approached Howie Winter, another mob boss who led the Winter Hill Gang, and offered to end the war. In May of 1972, the eldest Killeen was gunned down outside his home. While there remains some controversy, Bulger was rumored to have been the triggerman. The remnants of both the Killeen and Mullens gangs were subsequently absorbed into the Winter Hill mob.

Bulger was a cold-hearted murderer, but he was also smart. In this chaotic world, his steady leadership and ruthless demeanor brought him great success. Kevin Weeks also had this to say, “As a criminal, he made a point of only preying upon criminals…And when things couldn’t be worked out to his satisfaction with these people, after all the other options had been explored, he wouldn’t hesitate to use violence…Tommy King, in 1975, was one example…Tommy, who was a Mullens, made a fist…(Whitey) saw it…A week later, Tommy was dead. Tommy’s second and last mistake had been getting into the car with (Whitey), Stevie, and Johnny Martorano…Later that same night, (Whitey) killed Buddy Leonard and left him in Tommy’s car on Pilsudski Way in the Old Colony projects to confuse the authorities.”

Whitey’s allegiances shifted with the winds to his maximum advantage. Along the way, he worked as an informant for the FBI while continuing his overt criminal enterprise. In September of 2006, federal judge Reginald Lindsey ruled that the FBI’s botched management of Bulger as an informant had contributed materially to the 1984 death of a government snitch named John McIntyre. The judge awarded McIntyre’s family $3.1 million in damages as a result.

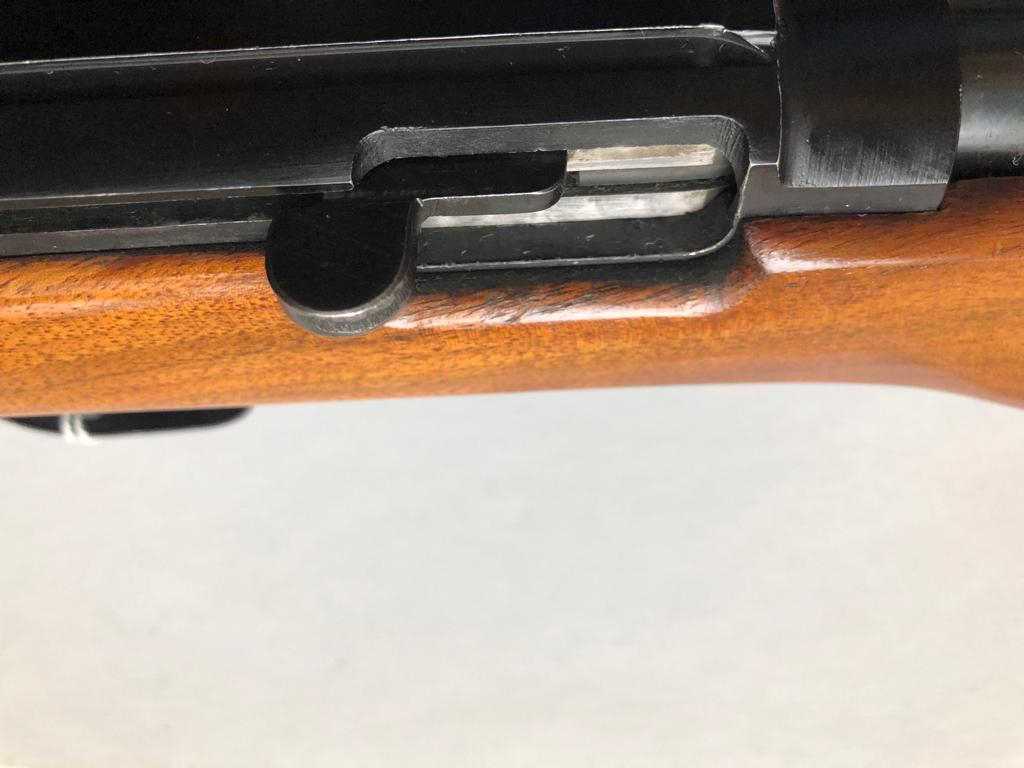

In 1982 Bulger and an associate approached a well-known local cocaine dealer with the street name of “Balloonhead” while he was traveling in a car with a friend. Bulger packed an M1 carbine, while his fellow hitter was armed with a full auto sound-suppressed MAC-10. The two men liberally sprayed the coke dealer’s vehicle at close range. Balloonhead and his buddy died on the spot.

Whitey thrived throughout by threatening and killing competitors and turned enormous profits through his sundry criminal enterprises. It was estimated that he made some $30 million solely by charging local drug dealers fees for operating on his turf. Bulger and his buddies also shipped, “91 rifles, 8 submachine guns, 13 shotguns, 51 handguns, 11 bullet-proof vests, 70,000 rounds of ammunition, plus an array of hand grenades and rocket heads,” along with substantial quantities of C4 plastic explosive to IRA terrorists in Northern Ireland.

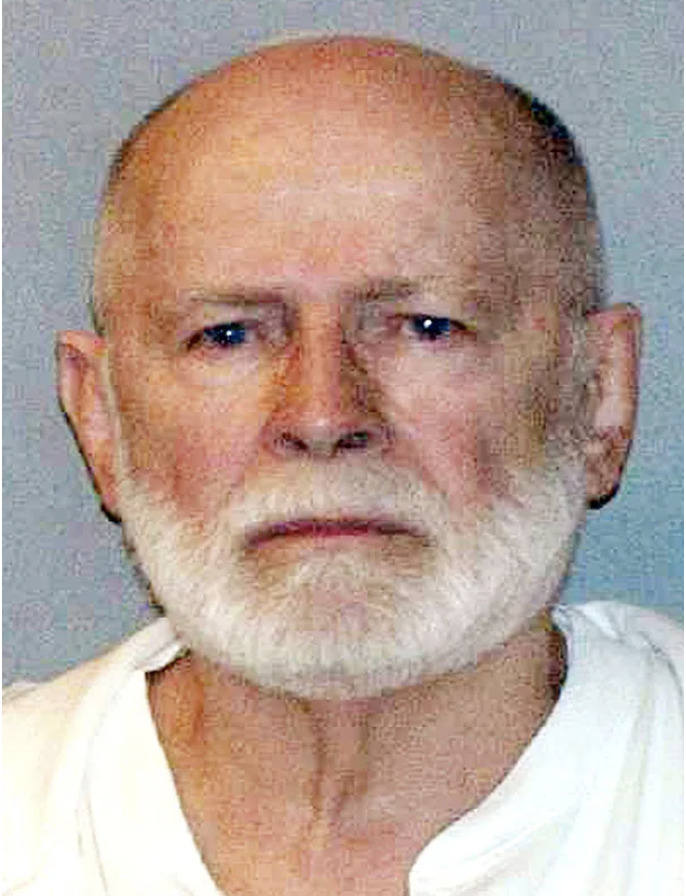

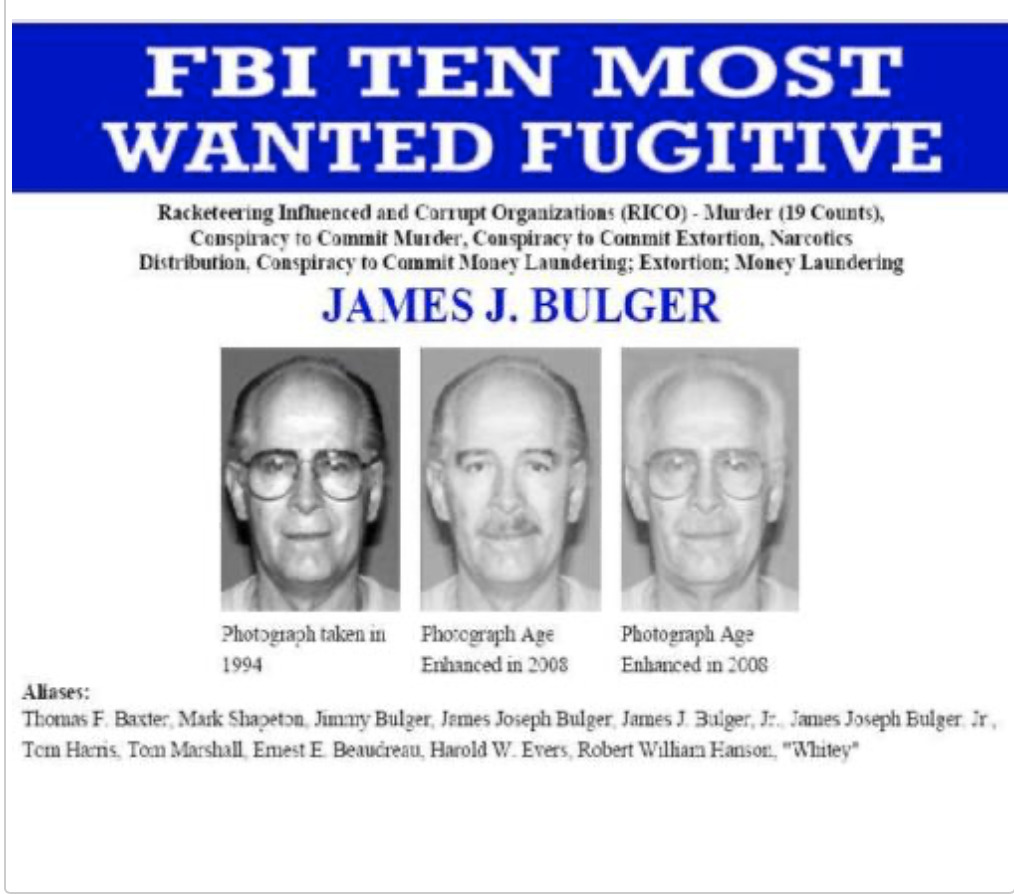

With the Law Enforcement heat becoming unbearable, Bulger fled Boston in 1995. He traveled widely in the US and Europe before finally being arrested in Santa Monica, California, in 2011 at age 81. He had been on the run for sixteen years and had been on the FBI’s Ten Most Wanted Fugitives list for twelve of those. The details of those years as a fugitive would require another couple of columns to fully explore. At the time of his arrest, Bulger had 30 firearms, several fake IDs, and $800,000 in cash in his apartment.

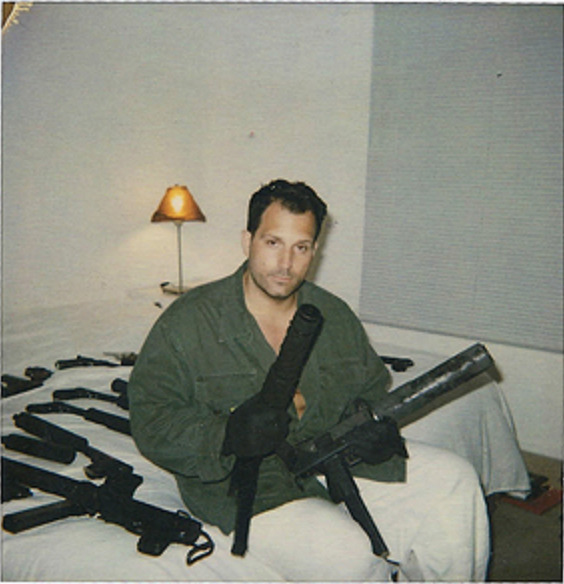

What spawned this project was a photograph of Bulger’s arsenal that was released after his capture. Bulger apparently had an affinity for 1911 pistols as there were several in attendance. He also had half a dozen fully automatic weapons. Dissecting his arsenal lends insight into the man and the brutal nature of his crimes.

Bulger’s handguns included a Walther P38, a Ruger .22 pistol, and a variety of revolvers. In addition to his weapons, police seized Law Enforcement badges and assorted carry gear along with fighting knives. However, it was the machine guns that were the most fascinating.

Bulger had a .45ACP MAC M-10 with an original WerBell-designed two-stage sound suppressor. There was also an M1 carbine with a civilian sliding “paratrooper” stock. His SP1-style AR15 included the original 20-inch rifle barrel and triangular handguards but had been fitted with a collapsible CAR-15 buttstock.

Whitey had a fascinating M3 Grease Gun that appeared to include an original GI OSS sound suppressor. These customized Grease Guns were some of the first operational sound-suppressed SMGs to see service alongside the Mk IIS suppressed Sten. We can only imagine where that particular weapon had been. The stash also included three well-worn 9mm German MP40 submachine guns.

Bulger was convicted in short order. He had been charged with a total of nineteen different murders. His first prison stop was the US Penitentiary in Tucson. Soon after his arrival a fellow prisoner nicknamed “Retro” stabbed the elderly criminal in the head and neck with a homemade knife, putting him in the prison infirmary for a month.

Bulger was subsequently moved to the US Penitentiary in Hazelton, West Virginia, on October 29, 2018. By this point, he was wheelchair-bound. The following day Whitey Bulger was beaten to death by multiple inmates armed with a padlock wrapped in a sock and a homemade blade. His eyes were all but gouged out and his tongue was nearly severed. In August of 2022 three inmates named Paul DeCologero, Sean McKinnon, and Fotios Geas were indicted for Bulger’s death. Their cases are winding through the legal system as I type these words.

Young American men will be taught the hard way that selflessness, courage, and their masculine instincts will get them 20 to life in prison.

This week, a brave Marine acted when no one else would to restrain a deranged homeless schizophrenic on a New York City F train who was, by all accounts, terrorizing people and shouting “I’ll hurt anyone on this train.”

“‘I don’t mind going to jail and getting life in prison,’ screamed the 30-year-old Jordan Neely, who had 44 arrests under his belt and an outstanding warrant for felony assault (he punched an old woman in the face), as he flailed around throwing items of his clothing. ‘I’m ready to die!’ In response, a 24-year-old Marine Corps veteran put Neely in a chokehold, incapacitating him and releasing him after he stopped struggling and passed out,” Inez Stepman wrote.

When Neely died at the hospital, all hell broke loose.

This is not the first time a courageous man minding his own business has put himself in danger to protect others. It’s happened many times, in fact. Toxic masculinity has saved more lives than penicillin.

But in this case, the erratic lunatic was black, the courageous restrainer was not just white but blond and handsome, and worst of all: the lunatic shuffled off this mortal coil when he arrived at the hospital.

Inevitably, the left’s muscle memory of how politically lucrative George Floyd’s 2020 death was for them kicked in. The Floyd Playbook could be run!

AOC fired up her Twitter and called his death a “murder.” Al Sharpton is polishing his diamond cufflinks before his press conference. Neely’s cousins are getting fitted for new suits before their Oval Office visit. Nancy Pelosi has already ordered the solid gold casket and white horse-drawn carriage for the funeral, which will be held after Neely lies in state in the Capitol. Kente cloth scarves are being passed out in the Old Executive Office Building. Kamala Harris’s speechwriter is ripping nitrous balloons as he crafts her eulogy. The whole band is getting back together!

In the aftermath, I tweeted this: “Strong men brave enough to intervene publicly when a deranged lunatic is terrifying people are going to be rounded up first; this is brilliant strategy for the Regime. Pick off the bravest and most selfless heroes first. Leave the cowards behind, who will fall in line fast.”

The worse the subway Viking’s fate is, the less likely any of us, the sane ones, will be tempted to lift a finger when they come for us, our friends, or our neighbors. If the Viking gets 20 years on Riker’s Island, plus some prison rapes and beatings for good measure as the guards look the other way — that’ll teach you boys a lesson.

Since literally the morning the first European settlers set foot in the new country, the ethos drilled into American men is to be strong, be brave, and be prepared to protect and defend your family, your homestead, and your fellow man. This is what men are for, after all. This is why God made them stronger than women. Those biceps are not just for deadlifting. Their main purpose is twofold: wielding a spear for the hunt, and wielding your fists or a sword for defense.

It feels like Good Samaritan laws have gone in and out of favor over time in America. For many years after 9/11, no able-bodied man boarded an airplane without first preparing himself to tackle a terrorist if he had to. Does that happen anymore? Or would the passengers laugh and whip out their phones as the terrorist slit a flight attendant’s throat? You will not go to jail for watching someone beat another person to death as you stream it live on social media. That’s perfectly acceptable now, even encouraged.

But every normal man I know would be unable to stand and watch a psycho assaulting an innocent stranger. My future husband once threw the first punch in a bloody fistfight against a much larger, much drunker man who was persistently harassing me and getting in my face late at night outside a bar in New York City. (My husband won, so I married him soon after.)

As an avid Twitter user, I probably see a dozen graphic videos a week of men doing the opposite: standing idly by, shouting approval and laughing, cameras out, as violent individuals assault, beat, rape, and shoot innocent strangers. This violence is almost exclusively black-on-white, or black-on-Asian.

In April, such a video made national news: a terrified young woman in downtown Chicago is knocked down and stomped on by a large mob during a “teen takeover” of the city. Where are all the videos showing the white-on-black and white-on-Asian stompings? I’m sure if they existed, AOC herself would be tweeting them out 24/7.

In this terrible, ugly, upside-down, zero-trust society I’ve been forced to raise a family in, I have developed new survival rules. I have instructed my husband and son to be cowards. That’s right: to do nothing if they are in a situation where a dangerous psycho is threatening violence to a stranger.

I have begged them to sit on their hands; to be one of the people who just watches, runs away, or calls 911. It goes against every chivalric instinct in their bodies, but I do not want them dead or in jail. Instead of being hailed as heroes for saving some old lady’s life, they would be tried as killers and put away for life.

My teenage son informed me he won’t go along with my surrender monkey ethos and is prepared to defend himself and others if he has to. This is a dangerous virtue for a boy to have in a blue city in 2023! Does he want his mother to get gray hair? Doesn’t he know how much good hair colorists cost these days?

I have failed as a mother because I forgot to teach my sons to be cowards.

This week’s watershed event on the New York City F train illustrates the blackpilling utility of my new rules. “Son, you see that damsel in distress over there getting her teeth kicked out by that filthy homeless man? You just sit tight and get off at the next stop and tell the nearest social worker. It’s not your problem.”

Podcaster Aimee Terese tweeted: “A man threatening the safety of everyone else in a tiny, highly populated, contained space, is a liability to himself and to others. The marine is a hero, and we need more men like him, which is why the left is wetting the bed about it. They don’t want that ethos to catch on.”

Neely was lynched by a racist and this racist will be made an example of. This is a teaching moment for Democrats — young American men will be taught the hard way that nobility, selflessness, courage, and their masculine instinct to defend the innocent are bad. Don’t be like this former Marine!

Mohammed Atta’s immortal words to the doomed passengers of American Airlines Flight 11 were “Just stay quiet and you’ll be okay.” Of course, it only applies to some of us. The raving maniacs on our subways, in our parks, and on our buses are free to live their best lives.

Democrat politicians have made forced passivity the new rule for normal people out in public. We are all cuckolds now. After all, what other sane choice do we have?

The U.S. Army’s latest multi-billion-dollar, high-tech small arms program is moving forward and, and it represents nothing less than an entirely new direction in U.S. military small arms development.

In April of last year, the Army announced that it had selected the winners of the Next Generation Squad Weapon (NGSW) competition: an infantry rifle and a light machine gun, along with a new cartridge and optical system that the pair would share. The news sent shock waves through the firearm and defense communities.

“We should know that this is the first time in our lifetime, the first time in 65 years, that the Army will field a new weapon system of this nature—a rifle, an automatic rifle, a fire-control system and a new caliber family of ammunition,” said Brig. Gen. Larry Burris, the Soldier Lethality Cross-Functional Team Director, at a press conference for the selection. Then, for emphasis, he added, “This is revolutionary.” For those of us in the civilian world, the announcement prompted questions about how and why our tax dollars are being spent.

The Problem

Two decades of constant combat usage of the U.S. military’s small arms have exposed some deficiencies in the current inventory. These include the effective range of the 5.56 NATO cartridge, the ability of M16-derived systems to deliver suppressive fire, the need for modularity to accommodate modern accessories and the weight that small arms systems add to an already-burdened soldier. The search for solutions to these problems are defined by a defense industry buzzword and a catchphrase: “overmatch” and “near-peer adversaries.” Overmatch is the ability to outperform the range, accuracy and lethality of the weapons used by the enemy of an advanced military with capabilities similar to those of the United States, such as Russia and China, and such militaries are seen as near-peer adversaries (see p. 26).

While the 5.56 NATO has a similar effective range to the Russian 5.45×39 mm and Chinese 5.8×42 mm cartridges (approximately 500 meters), that range would have to be extended for “overmatch.” Additionally, many arms that U.S. soldiers have often found themselves facing use the 7.62×54 mm R cartridge, as fired by PSL and SVD rifles and the PK series of medium machine guns, which have an effective range of approximately 800 meters.

Another factor determining the next cartridge’s performance is the fact that, during the past decade, ballistic body armor technology has improved and is less costly, making it possible for near-peer adversaries to equip their entire front-line forces with protection against conventional projectiles. Additionally, the U.S. military is increasingly encountering body armor in the hands of irregular forces and terrorists.

In 2017, retired Maj. Gen. Robert H. Scales stated the problem succinctly to the Senate Armed Services Committee: “Survival [on the modern battlefield] depends on the ability to deliver more killing power at longer ranges and with greater precision than the enemy.”

In response, the U.S. military has adopted limited numbers of extended-range specialty weapons, incrementally upgraded existing systems with “Product Improvement Programs” and improved ammunition with “Enhanced Performance Round” versions of both the 5.56 NATO and 7.62 NATO cartridges. But the limits of 75-year-old cartridge and arms designs have been reached. As Brig. Gen. William Boruff, Joint Program Executive Officer for Armaments and Ammunition, explained at the NGSW press conference, “the current 5.56 cartridge has been maxed out from the performance perspective.”

The History

From the conclusion of World War II, the U.S. military has sought solutions for increased lethality, greater hit probability and a lighter combat load in its small arms. When the Army announced the NGSW program in 2018, those who were skeptical that the effort would ever result in a finalized and adopted system were justified in their doubt. When the M16 was adopted in the early 1960s, the Army was already in the midst of a “future weapons” program—the Special Purpose Individual Weapon (SPIW). The SPIW program was an extension of Project SALVO, which itself was the result of the Army’s post-World War II analysis of how small arms were used by infantrymen in combat.

Its conclusion, which had already been reached by the Germans during the war, was that the most effective arm for an infantryman to carry was a fully-automatic rifle that fired an intermediate cartridge. The result was a compromise between the light weight and high volume of fire afforded by a submachine gun chambered in a pistol cartridge and the range, accuracy and ballistic payload of a full-size battle rifle. The groundbreaking “Sturmgewehr” design was quickly matched post-war by the Soviet Kalashnikov, and the rest of the world was left scrambling to update their arsenals.

Project SALVO worked on the idea that hit probability was increased by the greater number of projectiles you could throw at a target, essentially making a rifle into a long-range shotgun. The search for a lightweight “Small Caliber, High Velocity” rifle led to the adoption of the M16. The SPIW program sought to develop an arm that combined a grenade launcher with a rifle firing small, arrow-like “flechette” projectiles. It was abandoned in the early 1970s, and the M16 soldiered on.

By 1972, the Army was also looking for an arm that could cover the ground between the M16 and the M60 with the Squad Automatic Weapons (SAW) program. The program centered upon a new SAW-specific cartridge firing a 135-grain 6 mm bullet that gave a ballistic performance between the 5.56 mm and the 7.62 mm. While the Army eventually adopted the FN Minimi as the M249, it stuck with using the 5.56 NATO cartridge.

Soon after the M16A2 was adopted, in 1986, the Army began the Advanced Combat Rifle (ACR) program, the goal of which was once again to produce an arm that would increase hit probability on the battlefield. Many of the innovations developed during the SPIW program were examined again, including flechette rounds, duplex projectile loads and burst fire, along with new innovations such as polymer-case telescoping ammunition, caseless molded-propellant cartridges and the advantages provided by sound suppression and optical sighting systems. As no ACR candidate could provide “an enhancement in hit probability of at least 100 percent at combat ranges” over the M16, the program was canceled.

By the 1990s, the newest effort to replace the M16 was the Objective Individual Combat Weapon (OICW) program. The resulting arm combined a 5.56 NATO-firing rifle and a semi-automatic grenade launcher with a computer-assisted sighting system firing air-burst munitions, but it did not result in a practical design. An offshoot of this program was the further development of the Heckler & Koch G36-derived XM8, which was also eventually canceled.

The search for more effective small arms continued into the 21st century. In 2004, the Lightweight Small Arms Technologies (LSAT) program was formed to investigate polymer-case and caseless ammunition technologies. The program also developed a light machine gun prototype to replace the M249. An Individual Carbine competition seeking a replacement for the M4 ran from 2010 to 2014, but it ended without selecting a replacement. Ditto for the Interim Combat Service Rifle program. The M16 and its derivatives, it seemed, were here to stay.

The NGSW Competition

In many ways, the NGSW program was a ballistics-centric endeavor. Brigadier General Boruff summarized the purpose of the program when he stated it was, “all about energy on target and the longer ranges.” The Army knew the performance it wanted and sought an integrated system of a cartridge that provided those required ballistics, an arm to fire it and a sighting system that would give the average soldier the ability to utilize both to their maximum potential.

The Next Generation Squad Weapons program sought to select a new cartridge, a rifle (NGSW-R) and light machine gun or “automatic rifle” (NGSW-AR) to fire it and a “fire control” optical sighting system (NGSW-FC). Beginning in 2017, the requirements for the systems were announced. These stipulated the allowable size and weight of the new firearms and that they were to fire a cartridge of the submitting competitors’ own design that used a specific 6.8 mm bullet. The arm and cartridge combination were to be effective to 800+ meters. Initial competitors included Desert Tech, MARS/Cobalt Kinetic, FN America, General Dynamics, Textron and SIG Sauer.

The NGSW selection demonstrated a new process of developing, testing and adopting new technology with the Army’s use of “Cross-Functional Teams.” Each weapons system was given a “touch point” analysis by individual soldiers, with more than 1,000 soldiers providing 20,000 hours of feedback. In the Army’s estimation, the NGSW program condensed a process that would typically take eight to 10 years into 27 months.

In August 2019, the selection of three firearm finalists were announced. General Dynamics (its efforts were later taken over by Lonestar Future Weapons Systems) submitted a magazine-fed bullpup design for both the rifle and automatic rifle. The company partnered with Beretta for the design, which used the bullpup layout to incorporate a 20″ barrel in a firearm that would yield the ballistics the Army sought at a reasonable pressure, yet maintain an overall length less than the current M4. They partnered with True Velocity ammunition to develop a composite-case cartridge of conventional shape made of polymer and a steel base.

Textron, which had worked with the Army on its LSAT program, submitted a magazine-fed rifle and belt-fed automatic rifle of conventional layout. It partnered with H&K on the firearms’ designs, Winchester Ammunition on the ammunition and Lewis Machine & Tool for the suppressor. Its cartridge featured a “cased telescoped” design, meaning the entire bullet is contained inside a polymer case, which results in reduced weight and overall length.

The last candidates were submitted by SIG Sauer, which ultimately was awarded a 10-year, indefinite-delivery, indefinite-quantity contract capped at $4.7 billion. The initial phase is a $20.4 million dollar contract to provide 25 XM5s and 15 XM250s, along with ammunition, for further development. Eventually, the Army expects to procure 107,000 XM5 rifles and 13,000 XM250 automatic rifles. SIG’s submissions are described below; although note that the components of the NGSW program are still being developed, so the specifications and capabilities stated below are subject to change.

The 6.8×51 mm Common Cartridge

As a result of several ballistics studies, the U.S. Army determined that a 6.8 mm-diameter (0.277 cal.) bullet with a weight of approximately 135 grains would be optimal for what it believes will be the conditions of the future battlefield. For the NGSW program, the Army produced a “General Purpose Projectile” that uses a hardened-steel penetrator with a copper jacket and core similar to the M855A1. It was provided to the competing manufacturers who were tasked with developing their own cartridge that used the projectile, met the Army’s ballistic requirements and weighed less than a 7.62 NATO cartridge.

The cartridge SIG developed for its winning NGSW firearms has been designated as the 6.8×51 mm Common Cartridge (CC). As can be inferred from the “51 mm” part of its designation, the cartridge’s case is the same length as the 7.62 NATO, necessitating an “AR-10”-size firearm platform. The case is almost the identical diameter as well, meaning that capacity in a box magazine is the same as the 7.62 NATO cartridge. While the Army hasn’t revealed the exact ballistic performance of the new cartridge, the 6.8 mm CC delivers more velocity than the M855A1 with a bullet more than twice as heavy. The Army claims that the new chambering is superior to both the 6.5 mm Creedmoor and 7.62 NATO at ranges up to 800 meters and that it can defeat Level III body armor with non-armor-piercing ammunition out to 600 meters.

The new cartridge is not to be confused with the 6.8 Remington SPC, another cartridge developed at the behest of the U.S. military. Designed in the early 2000s, the SPC has the same overall length as the 5.56 NATO, meaning that existing M4 and AR-15-type firearms could be adapted to use it.

Since defeating body armor comes down, in large part, to velocity, every effort was made to get the maximum performance out of the new cartridge. The result was a chambering that operates at very high pressure. The Sporting Arms and Ammunition Manufacturers’ Institute (SAAMI) specification for the cartridge is 80,000 p.s.i., or about 30 percent higher than the operating pressure of similar cartridges such as 7.62 NATO or 6.5 mm Creedmoor.

When SAAMI certified the .277 Fury, the civilian version of the 6.8 mm CC cartridge, it included the warning that the cartridge, when loaded to pressures greater than 68,000 p.s.i., would “require cartridge case and/or firearms design that depart from traditional practices.” This is exactly what SIG did, developing a “hybrid” metal case for the cartridge. As the unsupported portion of a brass cartridge case that protrudes from the rear of the chamber and the primer pocket cannot handle these pressures, the SIG design uses a stainless-steel case head married to a brass case body. SIG claims the hybrid case design allows for an additional 350 f.p.s. in velocity over a conventional brass case.

In addition to its strength, steel is lighter than brass, so using it in what is the thickest part of the cartridge case keeps the overall weight of the loaded cartridge down. Though being nominally the same overall size, 6.8 mm CC weighs less than a 7.62 NATO cartridge.

The commercial .277 Fury launches a 150-grain bullet at 2,830 f.p.s. from a 16″ barrel—or approximately the performance you’d expect from a .270 Win. fired from a 24″ barrel. SIG also makes a reduced-power version of the .277 Fury cartridge that uses a conventional all-brass case and presumably operates at less than 68,000 p.s.i. The Army likewise plans to use a reduced-power version of the cartridge for training purposes and close-range combat scenarios where overpenetration is a risk.

SIG Sauer will be producing all of the Army’s 6.8 mm ammunition, using projectiles supplied by the Lake City Army Ammunition Plant, for the next few years. Lake City (a government-owned plant run by private contractor Winchester Ammunition) is building a new facility dedicated solely to producing the 6.8 mm CC ammunition that should be online by 2025 or 2026. By 2030, Lake City will take over as the lead producer of 6.8 ammunition. Lake City’s production of 5.56 NATO and 7.62 NATO will continue at current rates in the near future.

XM5 Rifle

In many ways, SIG’s winning firearms were the most conventional NGSW choices. Its rifle prototype, adopted as the XM5, is based on the commercially available MCX, which combines features of the M16 with a short-stroke piston and recoil-spring system that mimics the AR-18. SIG had already scaled up the 5.56 mm MCX to AR-10 size to accommodate a .308 Win.-class cartridge with its MCX-MR, which was a competitor in the Army’s Compact Semi-Automatic Sniper System program.

The XM5’s controls are M16-style rendered bilaterally for full ambidextrous use. The magazine release, bolt release and safety selector are present on both sides of the rifle, along with a bilateral, AR-type, charging handle. Additionally, there is a second non-reciprocating charging handle positioned on the left side of the receiver. The rifle utilizes an M4-style forward-assist device and case deflector. While having a general M4 familiarity, the exterior of the XM5 is also updated. The aluminum-alloy handguard features M-Lok slots, and there are built-in push-button sling swivel sockets on the handguard and receiver.

The XM5 mechanism uses a multi-lug rotating bolt. Function is provided by a short-stroke gas piston with an adjustable gas regulator. The upper and lower receivers are made of aluminum alloy with steel inserts in high-wear locations. Because of the gas-piston design and recoil springs contained within the receiver, the XM5’s stock not only telescopes like an M4 but also folds to the left side, and the rifle can be fired with the stock folded. The barrel has a tapered heavy profile and is held in place by a clamping system that uses two Torx-head screws that allow it to be removed in the field. The rifle is supplied with a two-stage match trigger, uses SR-25-pattern magazines and is capable of both semi- and full-automatic fire.

The XM5 is designed to be used in conjunction with a suppressor. In 2021, the Marine Corps announced that it would be supplying all of its front-line personnel with suppressor-equipped arms, to both make communication on the battlefield easier and to prevent the long-term health effects of loud noise exposure, and the Army seems to be following that lead. The XM5’s suppressor is also made by SIG and is based on its SLX series developed for U.S. Special Operations. The backpressure that a suppressor adds to a firearm can result in increased gases directed back at the shooter. The XM5’s suppressor is engineered to have a “flow-through” design that yields “low toxic fume blowback,” and SIG claims that using the suppressor results in no additional gas being expelled through the rifle’s ejection port. The suppressor is mounted by threading onto the XM5’s muzzle device and is held in place with a locking ring. Due to suppressor usage, the XM5’s 13″ barrel keeps the conventionally laid out rifle as compact as possible. With the suppressor installed, the XM5’s overall length is 36″, and it weighs 9 lbs., 14 ozs. There is no provision for mounting a bayonet.

XM250 Automatic Rifle

SIG’s winning automatic rifle design is based on the company’s MG 338, a belt-fed .338 Norma Mag.-chambered machine gun designed for U.S. Special Operations. The XM250 is an air-cooled, belt-fed design that fires from an open bolt. The action is gas-operated with a short-stroke gas piston system and is capable of both semi-automatic and fully-automatic fire. Its rate of fire is between 650 and 750 rounds per minute, depending on the ammunition used.

While SIG has been tight-lipped about the internal features of the XM250, some design features can be inferred from details found in the company’s machine gun patent applications. The XM250 uses the recoil-mitigation system of its .338 big brother, where the rotating bolt operates within a “barrel extension” that is fixed to the barrel and recoils within the outer receiver, with the bolt and barrel extension using separate recoil springs. SIG claims the XM250’s felt recoil is less than an M4. Although the XM250’s 16″ barrel is quick-change with the rotation of a collar, unlike the M249 it is not designed to be swapped under combat conditions. The XM250’s barrel-retaining system makes it field-adaptable for other cartridges in the 7.62 NATO class.

The XM250 is fed from 100-round disintegrating-link belts. The belts are housed in a polymer and canvas box that attaches below the gun with a “mag well” connection. Belts can be loaded into the gun whether the bolt is forward or back, in either safe or fire mode and with the feed tray open or closed. Unlike the M249, there is no provision that allows for the use of a detachable box magazine. The XM250 uses a left-side charging handle and has bilateral safety selector switches.

On the top of its receiver and handguard, the XM250 has a full-length Picatinny rail. It uses a feed tray cover that opens to the side to allow for mounting of optical systems without interference when the feed tray is open. Designed to be used with optics, the XM250 also has a set of offset back-up iron sights. The handguard features M-Lok slots, and the XM250’s bipod is made out of titanium to further save weight. The buttstock telescopes to multiple positions to adjust length of pull.

The XM250 is designed to use the same suppressor system as the XM5. Despite its visual bulk, the XM250 with bipod and suppressor weighs 3 lbs., 8 ozs., less than the M249 and is 13 lbs. lighter than the 7.62 NATO M240B. The size and weight of the XM250, along with its ability to fire semi-automatically, suggest that it could be used as a “rifle” in close-quarters engagements or, when combined with the new magnified optic, as a more precise “Designated Marksman Rifle” at longer ranges.

XM157 Fire Control System

The competition for an optical sight, or “Fire Control System,” included submissions from Vortex Optics and L3Harris (the former parent company of EOTech). The winner was Vortex’s offering, which was designated as the XM157.

The Fire Control System is the part of the NGSW program that represents the most radical leap forward in technology and capability. At the heart of the XM157 “Smart Optic” is a conventional 1-8X LPVO (low power variable optic) riflescope with a 30 mm objective lens and etched reticle that can operate without battery power. The “smart” side of the XM157 is information that can be projected as a digital Active Reticle onto a see-through display in the scope’s first focal plane. This allows for a customizable display that can include such information as ballistic drop or wind holds. The system has a built-in laser rangefinder and can compute other environmental factors, such as temperature, elevation, inclination and declination. This information is computed in real time by a unit that sits on top of the main scope’s body and adjusts the digital reticle accordingly. In addition to the rangefinder laser, the unit also contains visible and infrared aiming lasers. Again, some hints at the system’s possible capabilities can be gleaned from recent Vortex patents, such as a system that would allow the optic to display the number of rounds remaining in the magazine of the arm to which it is attached or the ability to display a virtual target for dry-fire practice.

While the XM157 sounds complicated, its function is simple and user-friendly, with all functionality displays seen through the scope. The system has passed all mil-standard optics tests of temperature, water immersion, dust, drops, shock, etc., so it’s as rugged as it is high-tech.

The system is powered by two CR123A batteries that will power the unit for “weeks” according to Vortex. While the actual weight of the system has not been revealed, according to Vortex, it is less than the combination of a conventional LPVO and ballistic computing system (presumably less than 30 ozs.). The entire unit is “modular and upgradeable,” meaning that newer capabilities can be added in the future, such as “augmented reality” modes that will allow soldiers to tag target points and share them wirelessly to other soldiers’ optics systems.

The XM157 will be made entirely in America of U.S.-made components, including the lenses. Vortex is scheduled to supply 250,000 systems over the next decade at the cost of up to $2.7 billion. As is apparent from that quantity, the XM157 is intended to be used not only on NGSW weapons but also on “legacy” platforms, such as the M4.

The Reaction

Expectedly, the announcement that the Army was replacing the rifle and cartridge combination that it has used for more than half a century was met with a swift reaction. One of the first criticisms involved weight. When it comes to physics, there’s no free lunch. The Army’s ballistic needs required a cartridge larger than the 5.56 NATO and a weapon larger than an M4 to fire it. A loaded XM5 with the XM157 optic will weigh about 3 lbs., 4 ozs., more than a loaded M4A1 with an M68 optic. With a full combat load, the XM250 outweighs the M249 by about 3 lbs., 8 ozs., while carrying 200 fewer rounds.

This brings up the second criticism of a decreased round count and increased weight for a combat load. The larger diameter of the 6.8 mm cartridge means fewer rounds can be stacked in a magazine of similar size to the current 30-round M4 magazine. According to the Army, the XM5 basic combat load is seven, 20-round magazines, which weighs 9 lbs., 13 ozs., in total. For the XM250, the basic combat load is four 100-round pouches at 27 lbs., 1 oz. For comparison, the M4 carbine combat load, which is seven 30-round magazines, weighs 7 lbs., 6 ozs., and the M249 combat load is three 200-round pouches weighing 20 lbs., 14 ozs., in total. This would result in a real-world total combat weight of 21 lbs. for the XM5 and 43 lbs., 6 ozs., for the XM250, versus 15 lbs., 10 ozs., for the M4 and 39 lbs., 14 ozs., for the M249.

Based on these two points, many critics bring up the specter of the M14, a large and powerful rifle designed for the plains of Germany that found itself in the jungles of Vietnam. But the counterpoint is that the Next Generation Squad Weapons signal a shift in the Army’s small arms doctrine. In a way, the NGSW program is the antithesis of the post-World War II Project SALVO. Increased weight and decreased round count suggests that the Army expects the NGSW weapons and optics system to allow soldiers to eliminate their targets at longer ranges with fewer rounds.

Trickle Down

Military innovation eventually trickles down to the civilian world, and, in the case of the NGSW, it has already arrived. The .277 Fury cartridge has been introduced commercially in the SIG Cross bolt-action rifle. A limited-edition, semi-automatic-only version of the XM5, marketed as the MCX-Spear, has also been offered by SIG. In September, the company announced the MCX-Spear LT, a mid-size platform based on the XM5 offered in 5.56 NATO, .300 Blackout and 7.62×39 mm in rifle, short-barreled rifle and pistol configurations.

Innovations that did not win the NGSW competition have also made their way to the civilian world. This spring, SAAMI certified its first composite-case ammunition manufactured by True Velocity. Currently available in .308 Win., there are plans for the company to commercially release 6.5 mm Creedmoor and 5.56 NATO composite-case cartridges in the near future.

Looking Forward

The NGSW weapons are scheduled to complete their operational test by the third quarter of 2023, with the first Army units equipped with the new firearms in the fourth quarter of that same year. The entire roll-out to the “Close Combat Force” (a classification that includes infantrymen, cavalry scouts, combat engineers and forward observers, in addition to special forces) will be dependent on when ammunition production can be ramped up to meet demand. Like the M17 handgun recently adopted, other branches of the U.S. military, such as the Marine Corps, may end up adopting the XM5 and XM250 as well. The M4 and M249 will continue to soldier on with second-line support troops.

The NGSW program marks a radical departure in U.S. small arms doctrine, pushing the envelope of conventional cartridge performance and pairing it with a state-of-the-art optical system that can help soldiers make hits to the limits of their weapons’ potential. In an age of UAVs and precision-guided munitions, the individual combat soldier is expected to become a more precise instrument, and the NGSW program is providing the tools for the job.

It demonstrates that, on an increasingly sophisticated battlefield, the infantryman isn’t being replaced by technology, but adapting to meet new challenges, as no amount of innovation will change the fact that wars are ultimately won by boots on the ground and with rifles that soldiers hold in their hands.

The ultimate judgement about whether the path taken by the NGSW program is correct will come on the battlefield.

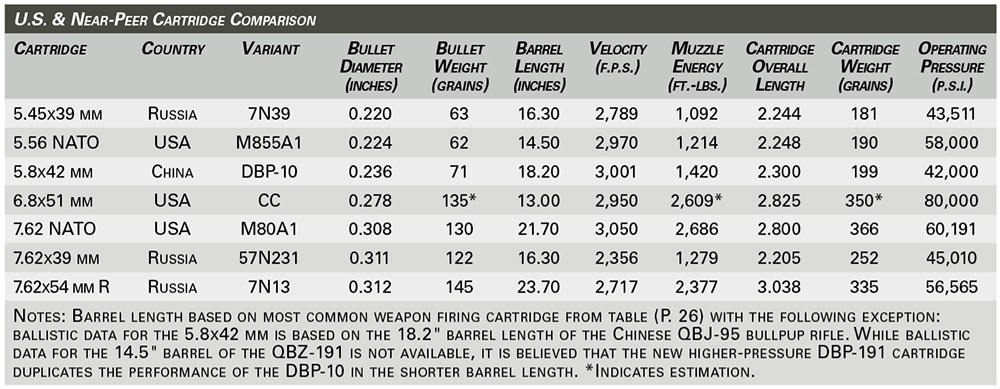

Conflicts in the early decades of the 21st century have highlighted deficiencies in U.S. small arms doctrine. To address these shortcomings, the military’s Next Generation Squad Weapons program settled on a new cartridge, rifle and machine gun. This table places current and future U.S. small arms in the larger context of firearms used by other nations.

Practically every soldier I have written about, I have made them airborne, and sent them to the 82nd Airborne Division. I have said that they are a cut above – elite, and they are. I will continue to recommend to anyone, man or woman, considering enlisting in the Army to take the “airborne option”. Some may say that the 82nd is simply a Light Infantry Division that jumps out of airplanes, once on the ground they work the same way as any other light infantry division.

The 82nd is just better trained because they are always on alert. No, once on the ground, they work differently. I have previously written about the trust and confidence the US Army has in individual soldiers. Nowhere is that more prominent than in the airborne units. The Airborne community has a sacred term – LGOPS (Little Groups of Paratroopers).

One the first things a Paratrooper is taught is the Rule of LGOPs. The story goes something like this: On the drop zone there is chaos; collections of around ten Paratroopers form. They are well trained, highly motivated 18-25 year-olds who are armed to the teeth, lack effective adult supervision, and remember the Commander’s intent as, “March towards the sound of the guns and kill anyone not dressed like you,” or something close to that. Happily they go about their work.

In July 1943, the first night mass parachute jump was conducted in Operation Husky, the invasion of Sicily. Then Colonel James M Gavin led the 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment, with the 3rd Battalion, 504th attached. Winds increased to 35 to 45 miles per hour just before the jump, but it was too late to cancel. They were already in the air approaching their drop zones. Planes were blown wildly off course and some gliders crashed.

Less than half of the paratroopers reached their rally points. The troops knew not only their unit mission, they knew the overall mission. When a small group of paratroopers got together they went into action. They cut every telephone line they found, they conducted ambushes and raids, and they accomplished every objective. That is where the 504th Parachute Infantry Regiment got their name “Devils in Baggy Pants”. The passage in a German Majors’ diary read; “American parachutists … devils in baggy pants … are less than 100 meters from my outpost line, I can’t sleep at night, they pop up from nowhere and we never know when or how they will strike next. Seems like the black hearted devils are everywhere …”.

In England, in 1944, training for the D-day invasion, the 18th Airborne Corps Commander, Major General Matthew Ridgeway, with the experience of the Italian operations, directed that the 82nd and the 101st Airborne Divisions conduct night jumps, which they did until injuries became too numerous.

Then they trucked the troops out into the training area, at night, and mixed them up. They also had intramural athletics, baseball, basketball, soccer, and flag football, but they couldn’t play unit against unit. They had to be mixed up, such as four players from B Company, 2nd Battalion, four from A Company, 1st Battalion, and four from D Company, 3rd Battalion. The idea was not only to get know troops from other units, but so they would learn to trust each other, because they knew there was a good possibility that the troops would be scattered in the jump.

The D-day invasion was led by the 82nd and the 101st Airborne Divisions, during the night of June 5th, 1944. Drop zones were missed; aircraft full of Troops were shot out of the sky; the fog of war that the US Army Air Corps faced over France directly contributed to creating LGOPs on the ground. These Paratroopers banded together, often creating teams of men from different companies, brigades, or even divisions.

In route to their rally points, these little groups of Paratroopers caused havoc behind the German lines by setting roadblocks and impromptu ambushes with the effect that many German commanders thought that they were facing a much larger force than what was actually there.

The mentality of a typical Airborne Soldier lends itself to an attitude of doing whatever it takes to accomplish the mission, facing any obstacle, and, most importantly, bravery because they have experience in overcoming a natural human fear: acrophobia, or the fear of heights.

For this reason, most paratroopers consider themselves better than others, because they have come face to face with their own mortality. The air is less forgiving than the sea, and if you find yourself in a situation where your main and reserve parachutes have failed, then you have the rest of your life to figure out how to deploy one of them.

They are a restless group who don’t take well to ambiguous direction or wasted time. This can be seen with the Operations tempo of airborne units. Often it feels as if the command is trying to force 36 hours of duties and responsibilities into a 24 hour day. And, as much as they complain and bitch, paratroopers love it. When they walk down the street, there is a swagger; that maroon beret looks better on their heads than a black beret looks on a leg’s because they have a sense that they earned it. In paratrooper language a “leg” is a sub-human soldier who is not Airborne. There is an intensity about how they carry out even simple tasks because, let’s face it, after you have jumped out of an aircraft while in flight, life is a little different and doing things half-assed just doesn’t make sense.

In training, with no enemy shooting at you, night jumps are, for some, less stressful than day jumps, because you can’t see anything, no ground or horizon. Inside the big jets you can hear, but in the C-130, which will forever be used to drop paratroopers, because it will carry 60 jumpers, and it will fly like a fighter, you can barely hear the person sitting next to you.

The C-130 is a four engine turbo prop – noisy. Jumpers are seated on red canvas seats along the wall of the fuselage and two rows, back to back, in the center. Parachute on your back, reserve on your chest, rucksack in a bag under your reserve, and your rifle in a canvas bag strapped to your side. Constant smell of exhausted jet fuel. Barf bags are issued. I never threw up on a plane, don’t know why, sat next to several who did.

The lights are on inside the airplane, because the jumpmasters must conduct their safety checks. The pilots have slowed the plane to 120 knots, and leveled off at 1,200 feet, if it was an actual combat jump it would be 800 feet, or less. When 10 minutes out, the jumpmaster gives the warning “TEN MINUTES”. OK, wake up get ready. The next command from the jumpmaster is; “GET READY”, then, “OUTBOARD PERSONNEL STAND UP’. That takes a minute or two, you’ve got 150 pounds plus of stuff strapped onto your body, you have to get up, turn around, unlatch your seat from the floor, fold it up and hook it. Then “INBOARD PERSONNEL STAND UP”. Next, “HOOK UP’. At that time outboard and inboard personnel form single lines on each side of the aircraft, and hook their static lines to a cable running along the wall of the fuselage. Then, “CHECK STATIC LINES”. Make sure your static line and the one on the jumper in front of you is straight and where it should be. Then, “CHECK EQUIPMENT”. Make sure everything is secure – adjust crotch. There are two jumpmasters, a primary and an assistant, plus two jumpmaster qualified safeties, who are at that time checking everybody. Then, ‘SOUND OFF FOR EQUIPMENT CHECK”. The last jumper, on each side, slaps the butt of the jumper in front of them and sound off with OK, which goes up the line until the two jumpers standing in front of the jumpmasters yell OK. The jumpmaster then commands “STAND BY”. Around that time the Air Force Loadmasters raise both doors and fold out a step plate at each door. Then you really hear the engines and rush of the blast. There is a light, about an inch and a half in diameter, beside each door, they have been red all the time. A jumpmaster is at each door, they have checked the surfaces of the doors for any irregularities. Each jumpmaster has a grip on the first jumper at his door, and he is watching the light. GREEN LIGHT!! Each jumpmaster commands “GO!”, and releases his jumper.

Everyone quickly shuffles to the door, there is no hesitation, just get out the door. I have been on full combat equipment jumps into unknown drop zones, when everybody couldn’t get out. The pilot ran out of drop zone and turned on the red light, had to circle around and make another pass over the crop zone, you’re standing, hooked up, with one hand holding your static line. As the plane banks and turns, your load gets heavier, the thought crosses your mind “just let me out”.

You step out, elbows tucked into your sides, hands on your reserve, feet and knees together, head down, chin on chest, a good tight body position. You count, one thousand one, one thousand two, one thousand three, one thousand four, you feel that great comforting tug of your main canopy opening. You reach up and grab the risers, and you look up into your canopy to make sure it is OK. You check for jumpers around you, if there is no moon, you won’t see them until you are really close.

Clean air, the planes move on, silence. In a few seconds, you drop the bag with your rucksack, it hangs on a line about 20 feet below you. At night, you can sense the ground, but you can’t tell for sure, you take up a good “prepare to land attitude”, feet and knees together, relax, face the parachute into the wind, don’t look for the ground. Landings are not soft, like sky divers. You try for a good parachute landing fall (PLF), balls of the feet, calf of your leg, thigh, buttocks, and push up muscle.

Down, WOW, good jump, don’t waste time, get out of that harness, get your weapon bag off, get your weapon out, and get your ruck sack. This is not combat, so you’ve got to turn in all that stuff. You “S-roll” your parachute, stuff it in the kit bag, attach your weapon bag, throw them on your back on top of your ruck and double time (trot) off the drop zone, and look for the turn in point.

Another good one in your jump log. GO AIRBORNE! ALL THE WAY!