Month: April 2023

S&W TRR8 two-piece barrel system is held in place by a special slotted nut. Image by TFB’s Rusty S from his TRR8 Review.

Welcome to another edition of TFB’s Wheelgun Wednesday, where we discuss all topics revolving around revolvers. Today’s topic comes from gunsmith Dave Lauck, of D&L Sports, in which he addresses one of the main detractors of the design of two-piece barrels for modern revolvers, which is that they can loosen under recoil over time.

The most prominent examples of two-piece barrels comes from the popular Smith & Wesson scandium framed Model 300 series, such as the 325, 327 (aka TRR8 and R8), and 329. While there’s no certainty that each revolver with a two-piece barrel will loosen, people have reported this problem, which can lead to less than optimal conditions for accuracy and safety, so let’s take a look at Mr. Lauck’s solution to loose two-piece barrels.

THE PROBLEM OF TWO-PIECE BARRELS, AND A SOLUTION

Another example of a two-piece revolver barrel, the Taurus Raging Hunter. Image from TFB’s Adam S’s review.

For those that are new to the concept of two-piece barrels, the steel, rifled barrel that interacts with the bullet is covered by a barrel shroud that incorporates the sights and rail systems for optics and weapon lights, if so endowed. The main advantage of this two-piece barrel system is weight savings, which is why Smith & Wesson utilize it on their lightweight scandium frames, thus a minimal amount of heavier steel is used for the overall design while keeping the aesthetics and features appealing.

As a side note, I’ve always loved the look of S&W’s 300 series revolvers. The second advantage of two-piece barrels is that the rifled barrel could be replaced if the owner shot it so much that the rifling begins to disappear, however, I’m guessing that aspect is rarely required with the exception of a few competition shooters.

Dave Lauck provided TFB his description of the two-piece barrel problem, and his resultant solution:

Multi piece revolver barrels can provide a weight savings by using various materials. Many shooters want to reduce weight on a carry gun. However, experience has shown that these barrel assemblies frequently come loose. Another problem is that it takes specialized tooling to correct the problem.

At DLS inc the goal is to solve problems with design improvements so they don’t occur in the field. The loose barrel problem can be solved with proper fitting and installing a barrel lock. While this custom work is being done, the barrel can also be given a precision, recessed and protected target crown, instead of the difficult to clean step crown. In addition, while the barrel is out of the frame the forcing cone can be properly cut and polished for best performance.

An image of the separated two-piece barrel system from the S&W 325. Image credit: DLSports.com

As you can see in the photo below, Mr. Lauck’s barrel lock is installed just aft of the barrel shroud on the top of the frame. The barrel lock is essentially a set screw that keeps the barrel from turning under recoil. The photo that follows is of TFB’s Rusty S’s S&W TRR8 in its factory condition without a barrel lock.

Image Credit: DLSports.com

Rusty’s S&W TRR8 without a barrel lock. Image credit: Rusty S.

Mr. Lauck also addressed another potential design issue with a feature also seen on the above-listed revolvers, as well as on some Ruger GP100 and Redhawk series of revolvers, the spring-loaded front sights. He describes the issue and his solution below:

Another problem that arises too often with spring loaded interchangeable front sights is they get caught on the top lip of the holster while re-holstering. When the revolver is pushed into the holster the front sight becomes unlatched from the retaining pin.

Then when the revolver is drawn again, the front sight falls out of the gun during the draw stroke, and is often lost under field conditions.

This is another concerning problem that should be prevented before it occurs. Once the correct front sight is selected to achieve proper zero on target, then the front sight should receive an additional cross pin to rigidly secure it in place, even during rough use. The sharp, fragile and shallow notch rear sight can be replaced with a DLS inc heavy duty rear sight to solve those problems.

Broad bodies shining white against the muted reds, greens and ochres of their adoptive home, you’d think that scimitar-horned oryx would be easy pickings for West Texas hunters, but that is very much not the case. On the sprawling, 295,000-acre 02 Ranch for the purpose of helping perform the initial field testing of a Ruger-made Marlin lever-action, I quickly learned just how incredibly wary these beasts can be and how surprisingly well their curved headgear blends into the thorny ocotillo and yucca plants that dominate that landscape.

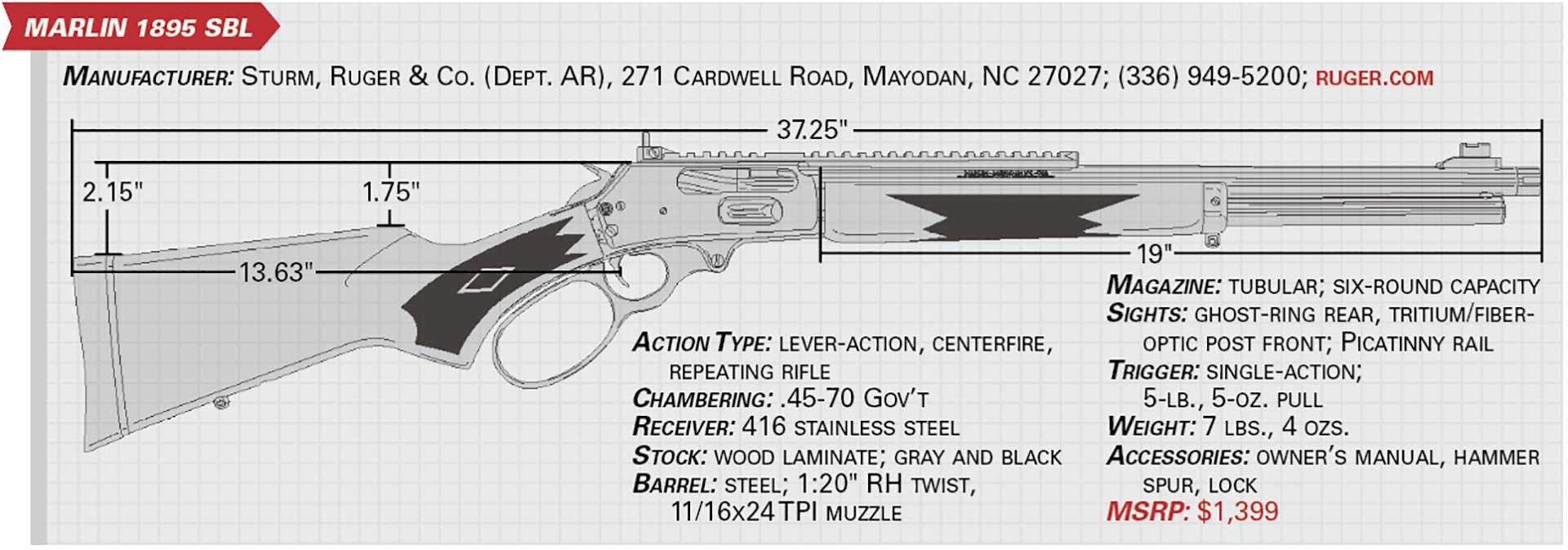

The specific Marlin in hand was the newly re-released Model 1895 SBL, chambered in .45-70 Gov’t, a hard-hitting but short-range cartridge, necessitating that I close the distance with an animal in order to take a clean shot—something that the free-ranging oryx seemed dead set against.

Adding 11/16×24 TPI threads to the end of the barrel allows for the installation of suppressors—such as the Silencer Central Banish 46 shown—or other muzzle devices, while an extended optics rail permits the use of either conventional or long-eye-relief scopes, or even a red-dot.

Numerous stalks had already failed, and the current one was on the verge. Guide Dave Callaway, with Backcountry Hunts, and I had been chasing a quartet of antelope for more than two hours when we noticed a single large male up on the hill about 900 yards ahead of us. As we continued following the group, it eventually became apparent that they were onto us and were heading full-steam to the next county, but the loner was still blissfully oblivious to our presence and was now only about 300 yards out.

We slowly scrambled to within about 150 yards and watched for a long while from the concealment of a tall Spanish dagger. Now agonizingly close but with only his head visible above the brush, we chanced moving in closer for a clearer shot at the bull, which finally came at right around 100 yards. Loaded up with Hornady’s 325-grain LEVERevolution ammunition, the first shot from the sticks knocked the bull to the ground, where he stayed for close to 30 seconds before surprising us by springing up and running for the hills, and a second hit grounded the hearty creature for good. The 1895’s action had been so smooth in readying that important follow-up shot that I hadn’t even been consciously aware of it until the excitement was over and the oryx was down.

We slowly scrambled to within about 150 yards and watched for a long while from the concealment of a tall Spanish dagger. Now agonizingly close but with only his head visible above the brush, we chanced moving in closer for a clearer shot at the bull, which finally came at right around 100 yards. Loaded up with Hornady’s 325-grain LEVERevolution ammunition, the first shot from the sticks knocked the bull to the ground, where he stayed for close to 30 seconds before surprising us by springing up and running for the hills, and a second hit grounded the hearty creature for good. The 1895’s action had been so smooth in readying that important follow-up shot that I hadn’t even been consciously aware of it until the excitement was over and the oryx was down.

While my successful hunt had already proven that Ruger’s Marlin was accurate enough for its intended application as a short-range hunting rifle, the process of dialing-in the Leupold scope had also hinted at an accuracy potential that was far more than just adequate. And, even at a glance, it was apparent that Ruger had made a few changes to the 1895 SBL that hadn’t been present on late-model Remington Marlins, so I was quite enthused to get a production gun sent in for a full evaluation.

While my successful hunt had already proven that Ruger’s Marlin was accurate enough for its intended application as a short-range hunting rifle, the process of dialing-in the Leupold scope had also hinted at an accuracy potential that was far more than just adequate. And, even at a glance, it was apparent that Ruger had made a few changes to the 1895 SBL that hadn’t been present on late-model Remington Marlins, so I was quite enthused to get a production gun sent in for a full evaluation.

Unlike Remington-era Marlins, Ruger is nickel-plating and spiral-fluting the 1895 SBL’s bolt—changes that both add functionality and a touch of flair.

On a foundational level, Ruger hasn’t done anything to alter the operation of the Marlin 1895; the company has merely sanded down a few rough edges—in some cases literally—and made a few tweaks. It is still a centerfire lever-action rifle with a solid-top receiver and an under-barrel tubular magazine, and cartridges are fed into the six-round magazine via a port on the right side of the receiver.

As SBLs in particular—models always intended to be the most garishly dressed guns at the otherwise stolid lever-action party—my test samples also featured polished stainless-steel receivers, extended optics rails, eye-catching black-and-gray laminate furniture and big-loop levers.

Instead of a separate grip cap, the new rifle bears a Marlin logo laser-etched directly into the wood.

Actuating the lever downward drops the locking block and pulls the bolt rearward, simultaneously extracting and ejecting the spent case, cocking the hammer and releasing a fresh round from the magazine onto the carrier. During the upstroke, the carrier levers upward, positioning the cartridge such that it can be guided into the chamber by the returning bolt.

Ruger has slimmed down the 1895 SBL’s wood-laminate fore-end (above) considerably, making it a better fit for most hand sizes. A new finish also gives the furniture’s checkered areas a much darker appearance.

The most obvious changes to the Ruger-made 1895 SBL are naturally the external ones. These include the addition of 11/16×24 TPI muzzle threads to the 19″ hammer-forged barrel and a noticeably slimmer fore-end. Also, rather than a discrete black pistol grip cap, the new gun instead bears Marlin’s horse-and-rider logo laser-etched directly into the wood, and the previous XS ghost-ring sights have been replaced by a HIVIZ set. Ruger is also nickel-plating the bolt, the rear 3.5″ of which now bears spiraling flutes; this is mostly for the sake of aesthetics, but it should help reduce drag a little bit as well.

But unseen inside the Ruger-made Marlin are also a host of small refinements that together add up to a far better fitted and finished final product than had been produced by Marlin in the past decade. Just a few of these include: improved thread timing of the barrel with the receiver, ensuring properly aligned front and rear sights; more precisely cut hammer notches, resulting in more consistent engagement with the sear and a cleaner trigger pull; and an improved chamber requiring fewer operations to machine.

But unseen inside the Ruger-made Marlin are also a host of small refinements that together add up to a far better fitted and finished final product than had been produced by Marlin in the past decade. Just a few of these include: improved thread timing of the barrel with the receiver, ensuring properly aligned front and rear sights; more precisely cut hammer notches, resulting in more consistent engagement with the sear and a cleaner trigger pull; and an improved chamber requiring fewer operations to machine.

Ruger has also placed particular emphasis on tight tolerances and effective part stack-ups: at each step in the process parts are gauged to ensure proper fitment—and, on stainless guns like the 1895 SBL, the metal is heat-treated prior to machining to avoid warping. All parts that interact with another part are tumbled to remove burrs, and edges throughout the gun, from the trigger to the lever to the loading port, have been softened for added comfort and a more refined presentation.

Ruger has also placed particular emphasis on tight tolerances and effective part stack-ups: at each step in the process parts are gauged to ensure proper fitment—and, on stainless guns like the 1895 SBL, the metal is heat-treated prior to machining to avoid warping. All parts that interact with another part are tumbled to remove burrs, and edges throughout the gun, from the trigger to the lever to the loading port, have been softened for added comfort and a more refined presentation.

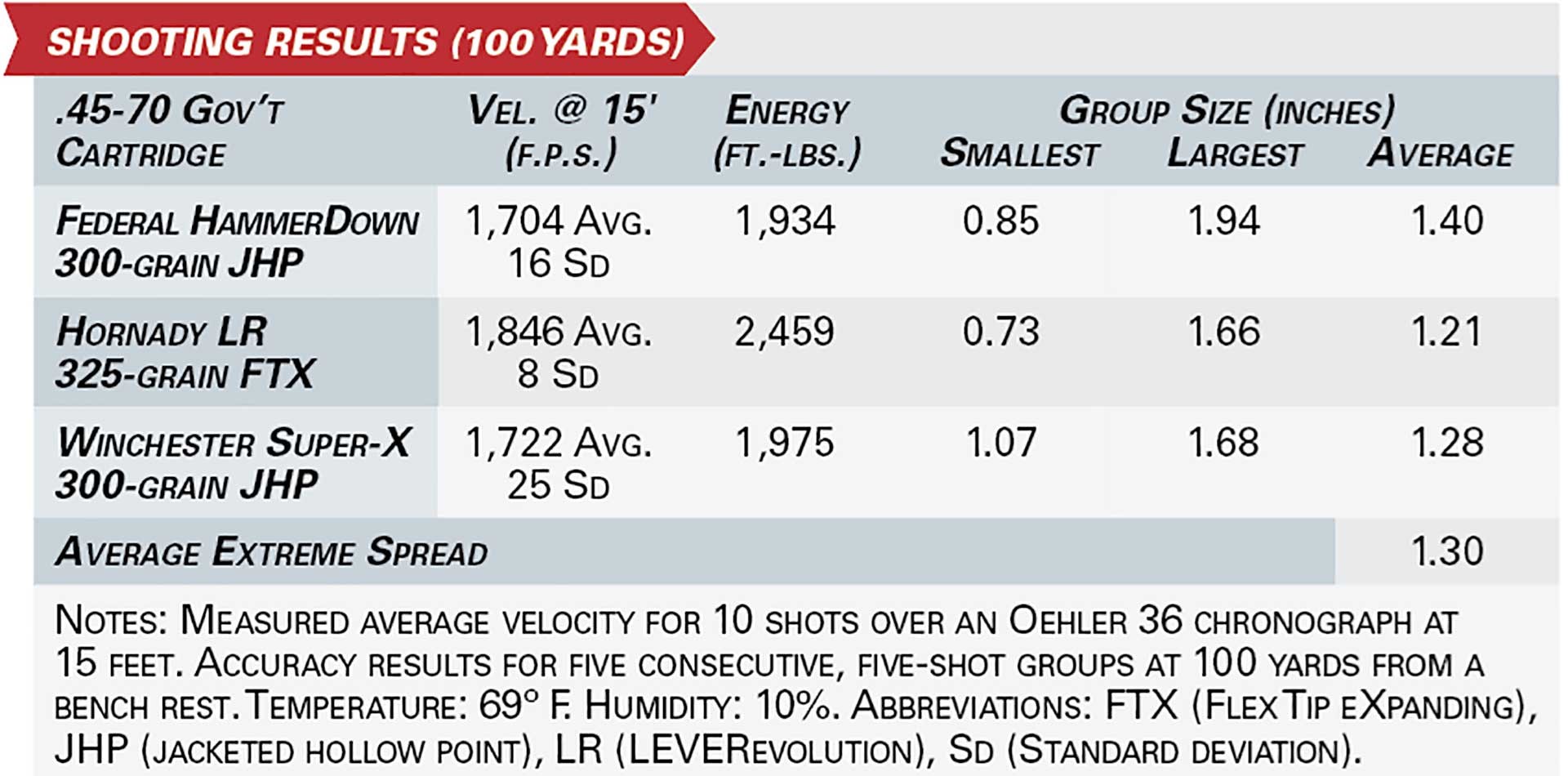

As can be seen in the nearby results table, the accuracy of the Ruger-made Marlin wasn’t just good for a lever-action—it shot well for a rifle of any kind—particularly given what a thumper the .45-70 is. The trigger’s single-action break had zero take-up, zero overtravel and was extraordinarily consistent; 10 trigger pulls averaged a 5-lb., 5-oz., release, with seven of those readings registering as either 5 lbs., 5 ozs., or

5 lbs., 6 ozs., on the gauge.

The Marlin name has taken something of a shellacking during the past 15 years or so, and yet, in spite of this, the brand remains much beloved among lever-gun fans.

As a result, if Ruger gets this re-launch right, it stands to win a lot of brownie points with a lot of shooters, and the two 1895 SBLs that I’ve handled extensively thus far certainly seem to indicate that a resuscitation of Marlin’s reputation is already well underway. Whereas “Remlin” became an unflattering pejorative over time, if these rifles are indicative of what the factory is producing in general—and I have no reason to doubt it—then “Mayodan, NC” on the side of a Marlin barrel may well come to be seen as a hallmark of quality.

Home-made Shooting Sticks