Month: November 2022

Milsurp Operator: M1 Carbine

FN M249 SAW

Enjoy! Grumpy

The myriad selection of rifle cartridges today has a metric ton of overlap, duplication, and some downright silly designs. Some of these designs boast wonderful claims, but not all of them measure up. In order to be overrated, you have to be rated at all, so that leaves some of the more obscure designs off the menu.

I’m well aware that I’m going to be taking a lot of flak for this article, no matter which cartridges I were to pick, so let me give you some details to start with. When you sit down to make your voodoo doll of me, you need to be as realistic as possible, I’m six feet tall, bald, blue eyes, and the goatee is graying. Accuracy counts in the voodoo-curse world as well.

That said, I have to pick five, and I know someone will come away with hurt feelings, but I’m going to throw caution to wind and do this anyway. “Overrated” is a tough term. It doesn’t mean that the cartridges I’m going to pick are bad, or even that they don’t work, it means that I feel that the glorification of them may not live up to the actual performance. Let’s roll.

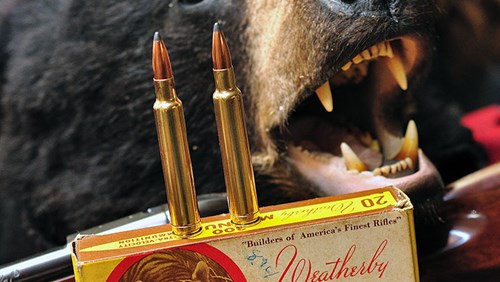

1. .300 Weatherby Magnum

I can feel the hot needles already. Roy Weatherby had a passion for the pursuit of velocity, and in some instances it made for a fantastic cartridge. However, the .300 Weatherby, based on a blown-out .300 H&H case, and featuring Roy’s signature double-radius shoulder, may have been the hottest on the market in the 1950’s, but it has been pushed off the stage. In my opinion, you can get field performance out of a .300 Winchester Magnum that is so close the game animals will never know the difference. Add in the costly ammunition and component brass, as well as the ramped-up recoil, and the scales lean even harder toward the Winchester case. If you want to really move .30 caliber bullets in a magnum length action, look to the .300 RUM or .30-378 Weatherby, just don’t shoot anything you intend to eat at close range.

2. .270 Winchester Short Magnum

Why do my feet feel like they’re on fire? When you have a cartridge that is as flat shooting and hard hitting as the venerable .270 Winchester, improving upon it isn’t easy. The Winchester Short Magnum series of cartridges have their own unique set of issues (they’re very finicky to reload for, not to mention the feeding issues), but to try and push the bullets even faster, out of a shorter and lighter rifle with more recoil, doesn’t make a ton of sense to me. The .270 Winchester is a fantastic long-range cartridge. The longer bullets start to eat up case capacity, and the caliber is generally limited to bullets that top out at 150 grains. The .270 WSM is too much of a good thing, in my opinion.

3. .220 Swift

Yes sir, that was a needle in my eyeball. Good thing I have a spare. How dare I insult the .22 centerfire velocity king? Well, here’s my thinking. The .22-250 Remington, which performs around 150 to 200 fps slower than the Swift, will hit distant targets very well, with less powder, a shorter action, and is every bit as accurate as the Swift cartridge is. Not to mention, the .22-250 doesn’t have that rim, which can make for feeding problems in a magazine rifle. I know, the Swift hits that illustrious 4,000 fps with 55 grain bullets, but the 3,800 fps generated by the .22-250 is more than enough for me.

4. .458 Winchester Magnum

The idea of replicating the ballistics of the .450 Nitro Express, in an easy-to-produce bolt action rifle, was a very sound one. However, Winchester’s claim has historically fallen short of the mark. The engineers shortened the blown out .375 H&H case to fit in a long-action receiver, and in the same stroke reduced case capacity to the point that it became a problem. If you’ve ever tried to handload for the .458, I’m sure the thought of compressing powder with a pogo stick (please DO NOT try this, it’s humor) has crossed your mind. Look to Jack Lott’s full-length design, as it’s much easier to achieve the velocities that Winchester intended when handloading, and there are more than enough factory loads available. Almost all of the African Professional Hunters I’ve met re-chamber their .458 Winchester into a a .458 Lott, or are saving up to do so.

5. .223 Remington

Yes, I said it. Look, the .223 works, and works well for most of its intended purposes. But, I truly believe if the U.S. Government hadn’t smiled upon it, the cartridge would have a small fraction of the followers it does today. I hear shooters tell me all the time about how it is a miracle-wrought-in-brass-and-lead, and proceed to boast of its heretofore unheard-of capabilities. I feel, for the hunters, that a .222 Remington is more accurate for close ranges, and the .22-250 Remington has a huge advantage in the velocity and accuracy department at all ranges. The .223, with the right twist rate, can use the heavier 69 and 77 grain bullets, where the slow twist of the .22-250 limits it to 55 or maybe 60 grains tops, but for me, the .223 isn’t the Holy Grail of cartridges that so many profess it to be.

There you have it, take it for what it’s worth, and let voodoo curses and author-bashing commence.

Georgia is becoming a popular destination for both new companies in the gun industry and those looking to escape the unfriendly confines of their historical homes in blue states like Massachusetts, Connecticut, and New York. In this case, though, it’s more that Georgia was the right choice for a brand looking to expand its reach in the U.S. market.

In July, Italian gun maker Beretta bought Norma Precision and other ammunition makers from RUAG International, a company owned by the Swiss government, for an undisclosed price. Norma Precision had already announced that it was moving its headquarters to Georgia, setting up a factory in the Savannah suburb of Garden City.

Norma said 88 current employees in Georgia would be offered transfers. Employees will make an average of $57,000 a year, said company spokesperson Rose de Vries.

Last year, Norma Precision said it imported more than 400 containers of ammunition from factories in Europe, while also delivering more than 30 million cartridges of ammunition made in the U.S. De Vries said Norma would also export ammunition from the Georgia plant.

… Beretta officials said they’re trying to expand the sales and brand of Norma in the United States. Pietro Gusalli Beretta, president and CEO of family-owned Beretta Holding, said Norma, which is rooted in Sweden, has been making ammunition in the United States for 12 years and has seen four years of “steady growth.”

Norma Precision has a interesting (and international) backstory. While it was sold to an Italian gun company by a firm owned by the Swiss government, Norma was actually founded in Sweden by a native of Oslo, Norway.

In 1902, a young man from Oslo, Norway, got off a train in the small Swedish community of Åmotfors. Ivar Enger had been sent on a mission by his brothers to find a suitable location for a bullet factory. Just before 1900, the Enger brothers obtained a few secret, French Balle D projectiles and, with the help of their ballistic engineer, Karl Wang, they developed a process whereby a boattail could be applied to a bullet in a very consistent manner. This gave the Enger brothers an edge.

Started in 1894, the brothers’ company was called Norma, and it’s likely the only company to ever come about as the result of a single rifle cartridge—the 6.5×55 mm Swedish Mauser. The adoption of that cartridge by the Swedish military created a demand for ammunition and jacketed bullets. Scandinavian target shooters and reloaders needed a tremendous amount of jacketed bullets because they could no longer create their own bullets from lead and compete with the modern, high-velocity, smokeless cartridges.

Norma erected its first factory in Åmotfors by 1911 and moved out of the two-room building originally acquired in 1902. In 1914, Norma started loading 6.5×55 mm Swedish ammunition using once-fired military brass. But not enough military brass was available to meet demand, so in 1917 Norma began making its own. Norma ammunition soon became world-class and was used to set two Olympic records in the ’20s and ’30s. During this period, the company had also begun to manufacture hunting ammunition.

World War II brought with it a demand from the Swedish government that Norma be put on a war footing. The factory grew from 150 to more than 600 employees, but Norma had to surrender its secret bullet-making process. During the war, Norma primarily made small arms ammunition but focused on hunting and target ammunition after the military contracts disappeared.

120 years of history in the books and now Norma Precision is writing a new chapter in the land of the free and the home of the brave (and Braves). How cool is that?

With Gov. Brian Kemp easily winning a second term, Georgia has cemented itself as one of the top environments for the firearms industry. The list of gun companies already operating in the state is fairly long and illustrious, but there’s still plenty of room to grow, and I suspect this isn’t the last announcement about new facilities and hundreds of jobs coming to the state thanks to gun and ammunition makers.

The intricacies of World War 1 small arms fill books due to the rapid advancement of technology and how warfare changed in a few short years. It’s easy to get wrapped up in calibers, firearm models, bayonets, and actions as you pour over the history of the world’s first Great War. As such, sometimes things get forgotten and the world finds itself in need of a reminder. If I asked you what rifle the American forces used in World War 1, for instance, you’d likely say the Springfield 1903. You’d be partially right, but only about 25% or so. The M1917 Enfield actually did most of the fighting.

The Springfield 1903 certainly served overseas, and if you asked video games and movies, then you’d be led to believe it was the only American service rifle fighting that war. The Springfield name is absolutely legendary, and at the time, the Springfield 1903 was the official service rifle of the United States. Yet, 75% of American troops carried the Enfield M1917, and only the paltry remainder actually carried the Springfield rifle.

This includes Medal of Honor recipient Alvin York who silenced machine gun after machine gun with his M1917 and M1911 pistol. However, if you watch the Gary Cooper rendition, he wields a Springfield M1903. If the Springfield 1903 was the American service rifle of the time, then you might be asking: why did the M1917 Enfield arm the whopping majority of American troops?

Well, my dear reader, it’s simple logistics.

The M1917 Enfield and A Tale of Victory

You see, Americans are typically a little late to World Wars. However, we often help our allies in some big ways once we show up. The Brits had recently changed rifles and calibers, and when World War 1 came around, they were in need of rifles… but they clung to an old caliber to simplify logistics. They couldn’t build their P14 rifles quick enough to meet their needs, so they contracted with American weapon manufacturers to produce more.

American factories were spitting out P14 rifles left and right, chambered in the old .303 British. This helped the British forces greatly, but by the time America got involved in the war, they had the exact same problems the Brits had. There weren’t enough rifles to go around. Specifically, not enough Springfield M1903 rifles.

So, they looked at the factories building Enfield rifles and planned to retool them to make America’s Springfields instead. Then someone had a much better idea. Let’s just make P14s for American forces.

It would be much faster to produce Enfields for America than to retool the factories for Springfield rifles. They would be chambered, however, in the American 30-06 U.S. Service cartridge and were modified as such to accommodate the round. Luckily since the original rifle was itself designed for a powerful new British round, it accommodated the American 30-06 just as easily. Thus the M1917 Enfield was born.

American forces eliminated the volley sights and added a 16.5-inch bayonet to the end. The Enfield M1917 would quickly deploy with American Expeditionary Forces and fight in the fiercest battles of World War One.

Inside the M1917 Enfield

M1917 Enfields were very robust guns. While many of us may think of bolt action rifles as light hunting rifles, these guns were from that. They weighed nearly 10 pounds, featured 26-inch barrels, and an overall length of 46.3 inches.

The M1917 Enfield held five rounds of .30-06 and could be loaded via individual rounds or through stripper clips. Stripper clips allow for rapid reloads via simple disposable clips that hold five rounds by their rim.

Soldiers aligned the stripper clip with the integral magazine of the weapon and pressed downward, loading the magazine rapidly and allowing the soldier to jump right back into the fight. It may sound slow by today’s standards, but it was pretty quick in its day.

The bolt throw and movement on the M1917 Enfield were rapid and smooth. Enough so that the Enfield rifles gained a reputation for having a faster firing rate than the Springfield rifles. At close range, a faster firing rate is quite valuable (as was the 16.5-inch long sword bayonet).

Accuracy In Combat

Americans and Western European forces placed a good amount of value on accuracy in their rifles, and that’s apparent in the M1917. It wore a peep sight that was suited for long-distance engagements. In that role, the sight allows a soldier to carefully aim and take a precise shot. That’s great on an open battlefield, but sucked for close-range fighting in the trenches.

The peep sight allowed the M1917 to be more accurate than the M1903 in the early days, but later models of M1903 incorporated them as well. However, the M1903 sights of World War 1 weren’t incredibly effective. They were too far from the eye, and the front sight was thin and hard to see. It also broke quite often.

Accuracy with the M1917 was top-notch, and with iron sights, an average shooter could produce three-inch groups at 100 yards. You take a skilled shooter like Alvin York, and you could be a real menace to the enemy with this rifle.

They were accurate enough that the military converted a number of them to sniper rifles with fixed power magnification optics. These rifles were equipped with Winchester A5 scopes which granted the user a fixed five-power magnification that greatly increased their ability to hit targets at long ranges.

The End of the Line

After World War 1 ended, the M1903 went back to being the bell of the ball, though the M1917 stuck around for a while. They were sent overseas and kept in reserves, and later when World War 2 broke out, they were distributed as Lend-Lease rifles. Soldiers in mortar and artillery units carried them into the next Great War until the M1 Garand shortage was over. The M1917 Enfield was a fantastic rifle, and it’s a shame it doesn’t get the respect it deserves.

Hopefully, we’ve helped spread the glory of the M1917 Enfield and the difference it made in the trenches, in Belleau Wood, in Cantigny, and beyond.