Month: November 2022

Hiram Maxim was good. John Moses Browning was better.

A friend once told Maxim, “If you want to make your fortune, invent something to help these fool Europeans kill each other more quickly!”

Maxim invented the single barrel machine gun in 1885. The Maxim gun could fire 600 rounds per minute and was put to good use in the Russo-Japanese War. It proved Maxim’s friend prophetic, providing a wall of lead from both sides in World War I. The British suffered the bloodiest day in their military history on the opening day of 1916’s Somme offensive, when 21,000 British soldiers were cut down by fire from the Spandau, the German version of Maxim’s machine gun.

John Moses Browning

In 1885, Browning was just getting started. He had already earned the first of his 128 firearms patents in 1879. By the end of the century he was perfecting the self-loading firearm, while also designing the Winchester 1894, the Browning Auto-5 shotgun, and Winchester 1897 pump action shotgun among numerous others.

As the 20th century began and inched toward war, Browning invented a number of semi-automatic pistols for Colt, including the M1911 that would be used in both world wars and remains a firearms mainstay to this day.

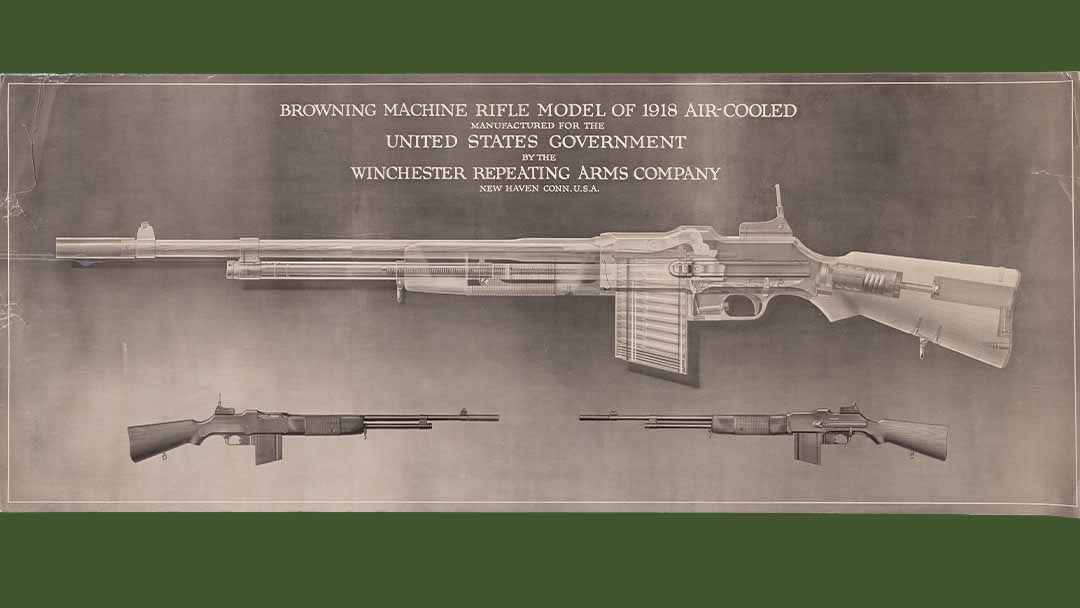

He also created machine guns, including the focus of this article: the M1918 Browning Automatic Rifle (BAR). Like the M1911, the BAR would be a key part of the U.S. military arsenal for both world wars and well into the second half of the 20th century.

A semi-automatic version of the BAR is available in Rock Island Auction Company’s June 22-24 Sporting and Collector Auction, and a full auto BAR will be on offer in the August Premier Auction.

The gun was Browning’s take on “walking fire,” the term given to a standard infantryman laying down covering fire as troops crossed “no man’s land.”

When the war started, the French’s lightweight automatic weapon was the Chauchat, also known by its more awkward name, the Machine Rifle Model 1915 CSRG. It weighed 20 lbs. and could fire in semi-automatic and full auto. French troops weren’t impressed with its flimsy metal parts and its tendency to jam, dubbing it “damned and jammed.”

BAR Time

As the United States felt the pull to war, Browning saw a need for a lighter machine gun that didn’t require several men to move, like the Maxim or British Vickers. He presented his prototype to Colt executives in February, 1917. A year later American military and Congressional leaders got to try out the Browning Automatic Rifle (BAR).

The gun was chambered in the plenty stout .30-06, like the Springfield M1903, the army’s standard issue rifle of the era. Colt, already burdened with a number of war contracts, passed off BAR production to the Winchester Repeating Arms Company and Marlin-Rockwell Corporation. More than 53,000 were made by the end of the war. Of those, Winchester produced 28,000, Marlin-Rockwell made 16,000, and Colt manufactured the rest.

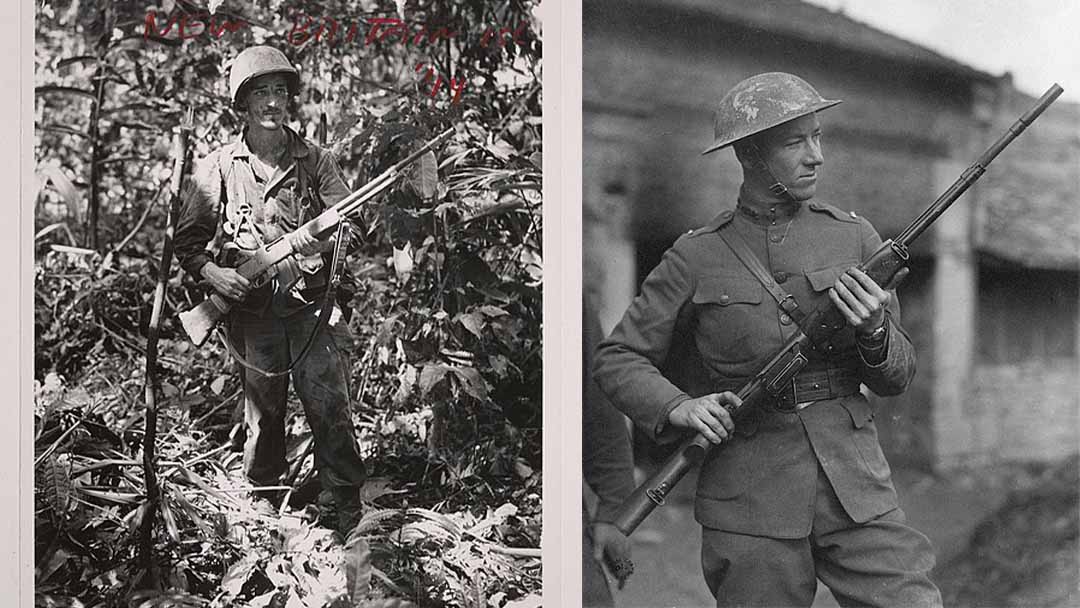

The U.S. entered World War I in April 1917. U.S. soldiers waiting on the BAR were issued the Chauchat and had the same problems as the French. The first BARs were delivered in France in June 1918 and the first combat use was recorded on Sept. 22, 1918 by the 79th Infantry Division. Lt. Val Browning, the son of John Browning, was one of the first to use the BAR.

Rather than a recoil-operated system like the Maxim, the Browning Automatic Rifle used a gas-operated long stroke piston rod with an open-bolt action for firing. It had a traditional rifle-style butt. Yes, the design was complex and machined, adding to the costs, but most importantly, it was reliable in terrible battlefield conditions. The initial BAR had select fire between semi-automatic and full auto.

A war department official wrote about the BAR, “The rifles were highly praised by our officers and men who had to use them. Although these guns received hard usage, being on the front for days at a time in the rain and when the gunners had little opportunity to clean them, they invariably functioned well.”

The 20-round magazine brought the BAR up short as a light machine gun because of frequent reloading and inadequate control when firing on full auto. It didn’t fit into the battle rifle category, either, because it was too heavy, and, again, lacked accuracy.

BAR Best Practices

Between wars, the Browning Automatic Rifle received some minor updates before getting its biggest redesign in 1938 when it became the M1918A2 with two rates of full auto fire, a flash suppressor, and iron sights. It also received a carrying handle and the buttstock was lengthened by an inch. Unfortunately, it added 4 lbs. to the gun.

Soldiers tended to shed some of what they felt were unnecessary accoutrements from the BAR to make it lighter.

The BAR was difficult to fire from the shoulder and because of its fixed barrel tended to overheat if fired too rapidly. Still, it was a staple in both theaters of World War II. Standard operating procedure was to issue one BAR per squad, but soldiers often worked to acquire more than one to give their unit more firepower. It also served as an anti-sniper weapon.

GIs learned the best use of the BAR was short three- or four-round bursts. Longer bursts lost accuracy and overheated the weapon.

More than 100,000 BARs were manufactured between 1917 and 1945. The BAR was also used by Argentina, Austria, Turkey, and Uruguay. It found its way into the second Sino-Japanese War (1937-1945), the Chinese Civil War (1927-1949), the Palestinian Civil War (1947-1949), the First Indochina War (1946-1954), the Bay of Pigs (1961), Cambodian Civil War (1967-1975), and the Turkish invasion of Cyprus (1974).

In the U.S. arsenal, the BAR fell from the spotlight when the M60 machine gun was introduced in 1957 though it still found use in Vietnam.

Colt Monitor

In 1931, Colt made 125 BARs for law enforcement, dubbed the Colt Monitor. The Monitor had the bipod removed, shortened the barrel and gas tube, added a Cutts Compensator, and a pistol grip. The compensator was to cut down on muzzle rise when firing off full auto bursts.

Militaries weren’t the only ones to use the BAR. Some infamous depression-era criminals got their hands on them, too — Bonnie and Clyde and Baby Face Nelson.

Bonnie and Clyde

Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow’s gang stole Browning Automatic Rifles from National Guard armories in Illinois and Oklahoma. Clyde shortened the barrel and gas tube, like the Monitor, and used custom magazines that welded two BAR mags together to increase the ammo load to 40.

The gang enjoyed success because of their use of high-powered autos and hard-punching weaponry, often outrunning and outgunning the law. It was a well-armed posse, including one deputy armed with a Colt Monitor that finally cut down Bonnie and Clyde.

Baby Face Nelson

Lester Gillis, better known as Baby Face Nelson because of his youthful countenance, was a ruthless criminal who wasn’t afraid of a gunfight, nor the law. He acquired a Colt Monitor through associates who had traveled to New York City.

Baby Face and his companion, John Paul Chase, were well-armed — with the BAR (Monitor), a Tommy Gun, and pistols — when they were confronted in Barrington, Ill., by federal agents. In an intense but brief shootout, one federal agent was killed and the second was mortally wounded, as was Baby Face who was believed by at least one author to be wielding the BAR at some point during the gun battle.

Despite the BAR’s brush with infamy, it is well remembered for being the full auto firearm that doughboys and GIs relied on to get the job done.

John Moses Browning’s legacy with repeating firearms is immense, whether it was shotguns, pistols, rifles, or machine guns. The Browning Automatic Rifle’s stopping power and reliability opened up warfare in the 20th century and provided a steady presence in the U.S. military’s arsenal for decades. A semi-automatic version made by Ohio Ordnance is in Rock Island Auction Company’s June 22-24 Sporting and Collector Auction and a full auto BAR is on offer in RIAC’s Aug. 26-28 Premier Auction.

Sources

A Battle at Barrington: The Men & the Guns, by Stephen Hunter

Browning Automatic Rifle: The Most Dangerous Machine Gun Ever?, by Paul Richard Huard

Walking Fire Concept: The 100 Year Legacy of the BAR, by Peter Suciu

“Rock in a Hard Place, The Browning Automatic Rifle,” by James L. Ballou

From the Taffin Dictionary of Sixgunning — “Perfect Packin’ Pistol is a title given to a sixgun or semi-automatic with a barrel not less than 4″, nor more than 5-1/2″, which can be carried easily all day in a well-designed holster, placed under a bed roll comfortably at night and can be expected to handle any situation which should arise.”

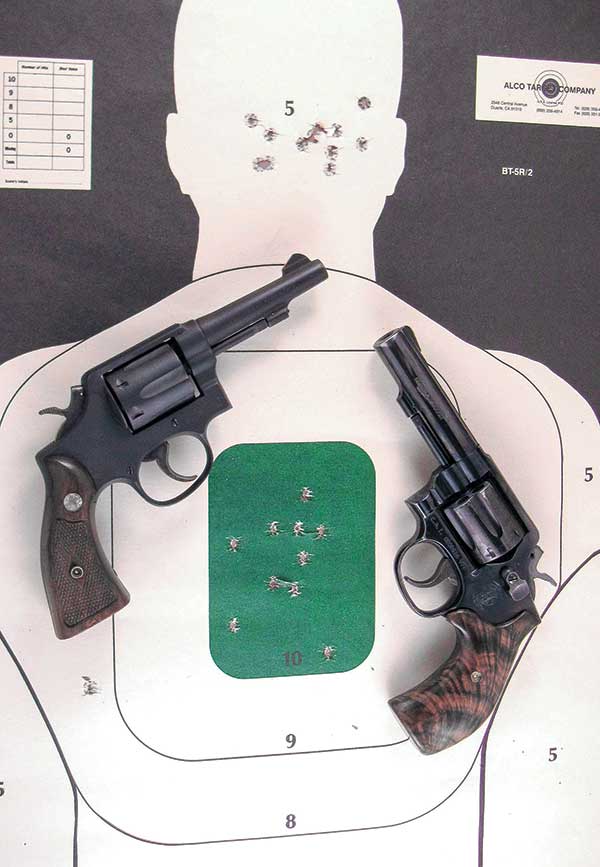

This definition takes in a lot of territory and obviously it depends where the bearer of such a PPP normally finds himself/herself. Whether daily travels take one on concrete, sagebrush, foothills, forests, or mountains, the encounters likely to occur have a great bearing on the caliber chosen have the duty. We will be taking a look at the epitome of Perfect Packin’ Pistols, namely the 4″ Double Action Smith & Wesson.

In The Beginning

To come up with the .38 Special, D.B. Wesson, along with his son, took a good look at the .38 Long Colt, the official U.S. Military Chambering at the time. The brass case was lengthened to accommodate 21-1/2 grains of black powder instead of the standard 18 and the bullet weight was increased from 150 grains to a round-nosed 158-grain bullet.

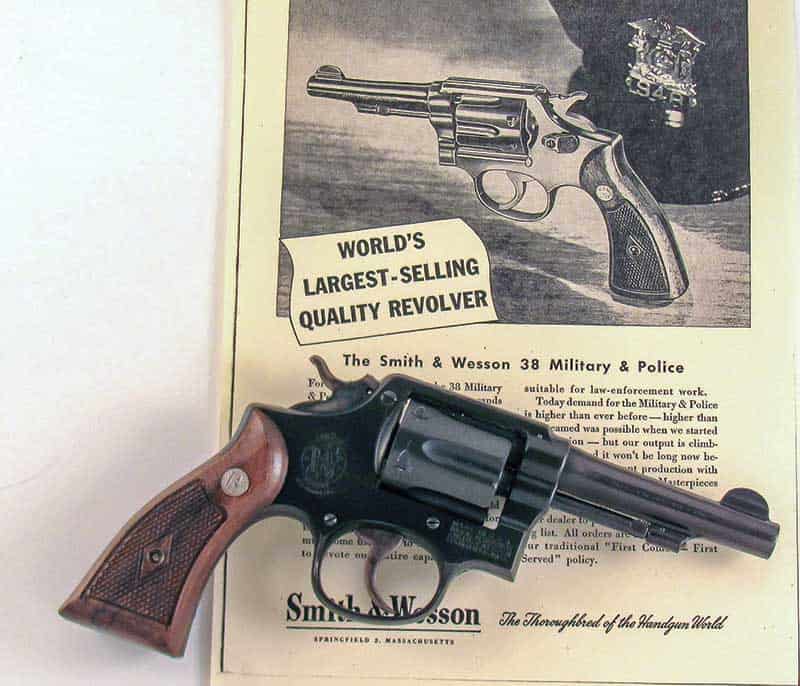

The new revolver was the first K-Frame and was given the name of Military & Police. For the next half-century plus, it would be found in the holsters of thousands upon thousands of police officers. Over the decades it would be made in the standard barrel configuration as well as a heavy barrel model in both blued and stainless finish. Bill Jordan especially liked the 4″ Heavy Barrel Military & Police in his exhibitions of fast double-action shooting.

With the coming of smokeless powder, the .38 Special was found to be especially accurate and from the very beginning the M&P was offered with target sights. Production of all civilian revolvers was shut down during WWII, however with the end of the war S&W began the development of what would become one of the finest target revolvers ever offered — the K-22.

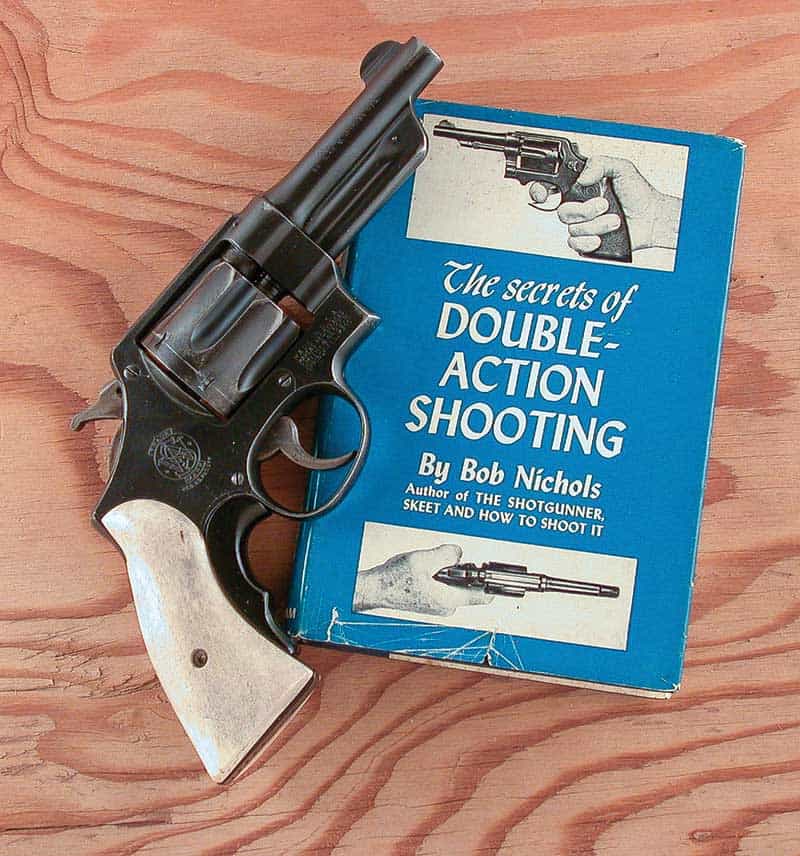

A Masterpiece

The K-22 was introduced in December 1946 and six months later the first K-38, followed almost immediately by the K-32, arrived. These were all given the title of Masterpiece, which was definitely fitting. I have examples of all three revolvers chambered in .22 Long Rifle, .32 Smith & Wesson Long and .38 Special. They were and are excellent target pistols but too long to be classified as a PPP. This matter was handled in 1950 with the arrival of the 4″ Combat Masterpiece. This magnificent revolver was available in both .22 and .38 with a few examples and .32 Long.

In 1957 the .38 Special Combat Masterpiece became the Model 15 with the .22 Long Rifle version known as the Model 18. For situations where either one of these chamberings will suffice, it would be pretty difficult to find a better choice than the Combat Masterpiece.

The .38 Special, although a great choice for target shooting or plinking, left a lot to be desired in its original round-nosed 158-grain version. After WWI ended, our society was rapidly changing from an agrarian one and many of those who had been content to stay on the farm were now gravitating to the large cities; couple this with Prohibition and the easy money to be made outside the law — as well as the arrival of a new breed of criminal robbing banks escaping in a super-fast V8 powered sedan — and peace officers certainly found themselves behind the times.

The standard .38 Special that had served law officers for nearly 30 years suddenly had to compete with criminals firing .45s and automatic weapons from an automobile. Those little slow moving .38s either bounced off car bodies and windshields or at the very best, offered shallow penetration. Something had to be done to help officers. Smith & Wesson decided a newer and, more powerful, .38 Special was needed and the result was the .38/44 Heavy Duty.

Smith & Wesson, in conjunction with Winchester, in 1930 changed the standard .38 Special using a round-nosed bullet at around 850 fps to a flat-nosed semi-wadcutter design traveling 300 fps faster, and also added a metal-penetrating version. To house this new round, S&W simply used their 1926 Model, or 3rd Model Hand Ejector .44 Special with a .38 Special barrel and cylinder. The result was a much heavier sixgun than the S&W Military & Police and it did an excellent job of dampening recoil even with the new load.

The Military & Police has always been a relatively easy gun to shoot, however this new .38/44 had such a slick action and heavy cylinder it almost seemed to shoot by itself once the trigger action is started. From my perspective it is the finest .38 ever produced; and I am certainly not alone in this assessment. The following came from Elmer Keith.

“About a year ago Smith & Wesson heeded the demand for a heavier .38 with their new .38/44. This weapon was designed primarily as a police weapon and brought out on their .44 Military frame, to my notion the best sized and shaped frame of any double action for my individual hand.”

A New Start

The introduction of the .38/44 sixgun and cartridge did get the .38 Special up off its knees. However, this was only the beginning. The fixed-sighted .38/44 Heavy Duty was offered in barrel lengths of 4″, 5″ and 6-1/2″. In 1931 this latter model was upgraded with the addition of adjustable sights and introduced as the .38/44 Outdoorsman. Just as its name suggests, it became very popular as a field and hunting sixgun. A few were made with the 5″ length and I am certain there were those who shortened the barrel to an easy packing 4″. I had planned to do this someday, however someday has not yet arrived. My itch has been scratched with the use of .38 Special loads in the 4″ S&W Highway Patrolman.

In the early 1930s Col. Doug Wesson and writer/ballistician Phil Sharpe began working together on a new project using the .38/44. Sharpe had the .38 Special lengthened and their work together resulted in one of the finest sixgun/cartridge combinations, the .357 Registered Magnum and the .357 Magnum itself. Smith & Wesson Historian Roy Jinks called it the greatest sixgunning development of the 20th century. I will not argue with the assessment!

I am always impressed by the Folks that can do stuff like this! Grumpy

I am always impressed by the Folks that can do stuff like this! Grumpy