Month: June 2022

SOVIET PPSH VS GERMAN MP40

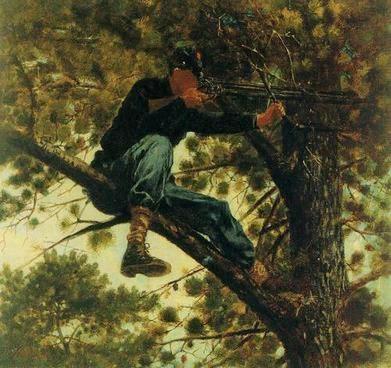

Sharpshooter on Picket Duty by Winslow Homer 1863.

To him, war becomes a game, but instead of the gamble of his skill at the target range, the rifleman is gambling his life on his ability to kill before he is killed.

~William B. Edwards, author, Civil War Guns~

A mechanical engineer, inventor, and expert marksman, Hiram Berdan was no novice when it came to firearms and ballistics. A champion sharpshooter, his development of improved musket balls, fuse timers, shrapnel shells, range finders, and patent for repeating rifles contributed significantly to the evolution of more efficient weapons.1 But his greatest design was the formation of an elite unit of expert sharpshooters for the Union Army during the Civil War. Though it has been speculated that it was not Berdan’s original idea but that of his good friend, Caspar Trepp, a former Swiss army officer and competitive marksman, it was through Berdan’s efforts that the 1st U.S. Sharpshooter Regiment was established.2

When the Civil War broke out in 1861, Berdan, a wealthy entrepreneur with influential political and industrial connections, presented his proposal for the organization of a topnotch sharpshooter regiment to President Abraham Lincoln and wrote letters to members of the War Department. Despite his lack of military experience, on June 15, 1861, he received permission to recruit from the loyal states.3 Though slow to start, a blitz of recruitment posters pitching the unique roles of sharpshooters, some offering bounties, resulted in an overflow of volunteers. These extras were sanctioned as the 2nd U.S. Sharpshooter Regiment under Colonel Henry A. Post.4

To ensure that only the finest marksmen were selected, Berdan set high criteria for acceptance. Only those men who could make ten consecutive shots within five inches of a bullseye at 600-feet distance would be allowed to join his elite regiment. Soon, newspapers featured stories about the sharpshooters’ exceptional skills. Large crowds began to attend their target practice sessions at Camp of Instruction in Washington, D.C., including President Lincoln and high-ranking military officers.5

Though committed and driven, Berdan’s lack of military leadership experience and arrogance created some animosity among his subordinates. Having to admit to himself that he had not a scintilla of experience in military tactical training and command, Berdan requested and received the assistance of Lieutenant Colonel Frederick Mears, a seasoned officer and drillmaster who provided the sharpshooters with basic training and skirmishing, scouting, and guard duty skills. He, too, eventually resigned.6

General Order 37 issued June 25, 1861, gave the recruits the option of securing their own rifles with the promise that they would be reimbursed $60 for each weapon, a promise that was never honored. Those who chose to use standard issue weapons were to receive breechloaders with “all the requisites for the most perfect shooting that the most skillful marksman could desire.”7 Acquiring proper arms for his sharpshooters turned out to be a drawn-out nightmare for Berdan, mostly due to the cantankerous, mulish head of army weapons.

General James W. Ripley, Chief of Ordnance, who has been widely criticized for his stubborn support of uniformity in standard weapons and his refusal to consider technologically advanced firearms, insisted on the continued use of Springfield rifled muskets.8 It soon became apparent to Berdan that the motley lot of target rifles the men had chosen for themselves created an ordnance nightmare: besides necessitating an assortment of ammunition, their heavy weight (14-30 pounds) required shooting from a rest and hindered a steady hand when shooting from the shoulder. Berdan caved in to Ripley’s “suggestion” and on July 19, 1861, ordered 750 Springfield rifles equipped with telescopic sights and lugs for angular bayonets.9 But the confusion regarding weapons for the elite unit didn’t stop there.

In September 1861, at Camp of Instruction in Washington D.C., representatives from several firearms companies demonstrated their respective breechloaders, hoping to cement contracts for large sales of weapons. Pvt. Truman Head of Company C, 1st Sharpshooter Regiment, had purchased his own Sharps 1859 model rifle, a .52 caliber, single-trigger weapon with a sabre bayonet. Introduced into service in 1850, the Sharps rifle had an effective range of 300 yards. Not only was the rifle renowned for its range and accuracy, its fast breech-loading design meant that a proficient rifleman could fire up to ten rounds per minute. Berdan requested a sample from the Sharps factory in September 1861 and subsequently placed a requisition for 1,000 rifles with modifications: the new Sharps would be equipped with angular bayonets, double-set triggers and rear sights adjusted to 900 yards. Ripley, offended that Berdan failed to collect the Springfields already allocated, refused to fill the order.10

By early December 1861, only companies C and E, 1st Regiment, were armed with target rifles. Concerned by the delay in acquiring the Sharps rifles and his men’s growing unrest, Berdan placed an order for 1,000 Colt 1855 breech-loading repeating rifles via General McClellan’s chief of staff, Col. Randolph B. Marcy, with President Lincoln’s endorsement. Ripley, enraged that Berdan had gone over his head, appealed to President Lincoln to cancel the order. Lincoln responded, “Understanding this to be substantially an order of Gen. McClellan, let it [the order] be executed.”11

The first 1,000 Colt rifles were issued in February 1862, with the understanding that these would be replaced by the superior Sharps weapons upon their delivery. Unfortunately, the Colts had two major defects: a tendency to fire some or all of its chambers at once and a propensity to spray lead shavings from between the cylinder and the barrel, causing slivers to become embedded in the skin.12 But when news came that the rebels had evacuated Manassas, signaling the start of the Peninsula Campaign, the men reluctantly took up their Colt and target rifles and forged ahead.13 The sharpshooters finally received the first shipment of 100 Sharps rifles on May 8, 1862.

On the battlefield, the sharpshooters wore distinctive hunter green, wool uniforms with green felt caps and leather leggings which served as camouflage. Gray overcoats and hats to blend in with winter’s backdrop were soon discarded lest the sharpshooters be confused for Confederates.14 Instead of forming traditional battle lines, they fought as skirmishers, spreading themselves out, making them tougher targets for the enemy. They also adopted guerrilla-style tactics that were both effective and deadly.

The sharpshooters saw their first action on April 5, 1862, during the Peninsula Campaign, when they picked off artillerymen manning Confederate batteries one by one during the Siege of Yorktown. Cpl. William L. Sankey wrote to his parents,

“The sharpshooters had the post of honor, the advance guard of Porter’s division … [at Big Bethel] we immediately deployed as skirmishers and closed in towards the fort…As fast as a head would appear over the earthworks, our boys would pick him off. The enemy must have thought there was a large body of us for we each had a five shooter. The rifle [Colt] did good execution that day.”15

Berdan’s Sharpshooters helped fight several rearguard actions during the Union’s retreat at the Battle of Malvern Hill. While the Peninsula Campaign ended in a humiliating Union withdrawal, the men in green quickly established themselves as the elite of the Union Army. They would continue to serve with distinction during the bloodiest battles of the war: Second Bull Run, Antietam, Fredericksburg, and Chancellorsville.16

In July 1863, they intercepted the rebels at the small farming town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania in one of history’s biggest and bloodiest battles ever fought on American soil. At Devil’s Den and the Peach Orchard, their actions significantly delayed the Confederate assault, giving vital time for Union troops to organize defenses on the high ground outside of town. At Seminary Ridge, the 1st Sharpshooter Regiment supported by 200 troops of the 3rd Maine Infantry held off an entire Confederate brigade.17

With Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant in command, the Army of the Potomac and the 1st and 2nd U.S. Sharpshooter Regiments took part in the most ruthless battles of the Overland Campaign: The Wilderness, Spotsylvania Court House, and Cold Harbor. On June 9, 1864, Union troops laid siege to the rebels at Petersburg. Virginia. Berdan’s Sharpshooters again distinguished themselves, but it would be their final engagement of the war.

One of the most famous of Berdan’s Sharpshooters was Private Truman “California Joe” Head, a fifty-two-year-old, mild-mannered hunter and fur trapper from Otsego County, New York. A lifelong bachelor, Joe had made out a will upon his enlistment leaving $50,000 in trust for the care of disabled Union soldiers should he be killed. He served with distinction as a scout and sharpshooter during the Peninsula Campaign, where his exploits in the Siege of Yorktown and the first Battle of Cold Harbor were published in newspapers across the North, making him somewhat of a folklore hero. One story described how Joe and his fellow comrades picked off several Confederate troops attempting to fire a large thirty-two-pound cannon which remained silent, thanks to their efforts18. California Joe was discharged from the Army in November 1862 due to the rapid deterioration of his eyesight.19

On March 11, 1893, the U.S. government awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor to Vermont native, William Y.W. Ripley, a former Lieutenant Colonel with the 1st U.S. Sharpshooter Regiment. During the Battle of Malvern Hill on July 1, 1862, Ripley led a relief force to aid his sharpshooters, who were under heavy fire. A bullet struck Ripley in the leg, forcing him off the field, but his actions helped save the lives of his men and ensured victory for the Union Army that day. He was the only one of Berdan’s Sharpshooters to earn the Medal of Honor.20

As for Hiram Berdan, he resigned from his commission on January 2, 1864, and went on to develop the Berdan Rifle, a popular firearm that was the primary weapon used by the Russian Army from 1870 to 1895. Of all his many great innovations, the U.S. Sharpshooter Regiments of the American Civil War may have been his greatest creation.21

NOTES

[1] Charles Augustus Stevens, Berdan’s United States Sharpshooters in the Army of the Potomac, 1861-1865 (St. Paul: Price McGill Co., 1892), 526-527.

[2] Roy M. Marcot, U.S. Sharpshooters: Berdan’s Civil War Elite (Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2007), 8-10. Frederick Phisterer, New York in the War of the Rebellion 1861-1865 (Albany: J.B. Lyon Co., 1912), 4313-4315.

[3] The 1st and 2nd U.S. Sharpshooter Regiments were recruited from the loyal states of New York, New Hampshire, Vermont, Michigan, Wisconsin, Minnesota, Pennsylvania, Maine. Massachusetts had two companies which trained with the 2nd Sharpshooters Regiment but were never a part of Berdan’s SS. An independent unit, they became known as Andrews Sharpshooters. Marcot, U.S. Sharpshooters, 22-23. Gerald L. Earley, The Second United States Sharpshooters in the Civil War: A History and Roster (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., 2009), 8.

[4] Stevens, Berdan’s United States Sharpshooters , 4.

[5] Ibid., 9-13. “Colonel Berdan and His Sharpshooters,” Harper’s Weekly, August 24, 1861.

[6] Marcot, U.S. Sharpshooters, 27-28.

[7] William Y.W. Ripley, Vermont Riflemen in the War for the Union 1861-1865 (Rutland: Tuttle & Co., 1883), 10.

[8] Stevens, Berdan’s United States Sharpshooters, 7. Peter Tsouras, “Civil War Firepower Denied!” HistoryNet. Last modified June 1, 2017.

[9] Marcot, U.S. Sharpshooters, 11-12.

[10] Martin Pegler, Sharpshooting Rifles of the American Civil War (London: Osprey Publishing, 2017), 25-31. Marcot, U.S. Sharpshooters, 48. Bob Carlson, “Sharpshooter Weapons in the American Civil War,” American Society of Arms Collectors, Spring 2013, 10-13.

[11] William B. Edwards, Civil War Guns (Harrisburg, PA: Stackpole Company, 1962), 212-215. John Plaster, History of Sniping and Sharpshooting (Boulder: Paladin Press, 2008), 153.

[12] Marcot, U.S. Sharpshooters, 55-57. Jack Coggins, Arms and Equipment of the Civil War (Mineola: Dover, 2004 reprint), 36-37.

[13] Stevens, Berdan’s United States Sharpshooters, 27. Ripley, Vermont Riflemen, 15-17.

[14] Marcot, U.S. Sharpshooters, 33-37, 40-43.

[15] “From the Army at Yorktown, A Letter from a Sharpshooter,” Albany Evening Journal, April 15, 1862.

[16] Stevens, Berdan’s United States Sharpshooters, 142-245. Rob Wilson, “Trial by Fire for the U.S. Sharpshooters at Yorktown” Parts 1-3, Emerging Civil War, June 26, 2018.

[17] New York State Monuments Commission for the Battlefields of Gettysburg and Chattanooga, Final Report on the Battlefield of Gettysburg Vol. III (Albany: J. B. Lyon Co., 1902), 1071-1078. From 1st U.S. Sharpshooters Regiment’s Capt. F. E. Marble’s diary, July 2, 1863, an ode to his regiment. Timothy J. Orr, “On Such Slender Threads does the Fate of Nations Depend,” NPR: Gettysburg Seminar Papers 2006, 124-.143.

[18] Stevens, Berdan’s United States Sharpshooters, 59. Edwards, Civil War Guns, 217.

[19] Stevens, Berdan’s United States Sharpshooters, 49-51., Marcot, U.S. Sharpshooters, 30-31. “California Joe,” Harper’s Weekly, August 2, 1862.

[20] William Y. W. Ripley MOH citation, Military Times Hall of Valor Project, March 11, 1893.

[21] Stevens, Berdan’s United States Sharpshooters, 513, 526-527.

The officer’s back had been to me, but when he turned to face me I was surprised to see the lieutenant’s bars on his uniform collar. “I guess I am,” he said.

Yes, he was the highest-ranking officer at the scene, but he was not in charge. No one was, that is, not until I and another sergeant from the neighboring division harnessed the energy of the amassed officers and put it to constructive use.

That lieutenant may have managed his officers efficiently on a daily basis, he may have turned out well-written watch commander’s logs, and in all other ordinary circumstances he may have performed every duty expected of a patrol lieutenant satisfactorily. But in that moment of crisis, with his wounded officer’s life on the line, he failed.

This is often what happens in police work, a field in which adherence to the chain of command is relentlessly emphasized. Such adherence serves the organization well under mundane conditions, but when a crisis occurs, as happened in Uvalde, Texas, on Tuesday, the chain of command does not always produce the leader the circumstances demand. When rapid, tactical decisions are called for, the highest-ranking officer at the scene may not be the most qualified to make them, and in most cases is guaranteed not to be.

If the current timeline of events is accurate (and bear in mind there have been several corrections since Tuesday), the first 911 call regarding trouble at Robb Elementary School came in at 11:30 a.m., and the gunman was not shot and killed until 12:50 p.m. As I write this, much of what occurred in the intervening 80 minutes is yet to be revealed, but it has been reported that for much of it, 19 police officers staged in the hallway outside the classroom but did not attempt to make entry, even as 911 calls from inside continued to come in to police dispatchers.

The incident commander at the time, we are told, was the school district’s police chief, whose qualifications for leadership under these circumstances will be the subject of much debate in the coming days. Steven McCraw, director of the Texas Department of Public Safety, addressed the issue with reporters on Friday. “The on-scene commander at that time believed it had transitioned from an active shooter to a barricaded subject,” McCraw said. “It was the wrong decision. Period.”

Of course the wrongfulness of the decision is apparent now, in retrospect. But in the U.S. Supreme Court decision of Graham v. Connor, we are admonished to evaluate police actions not with the benefit of hindsight, but rather “from the perspective of a reasonable officer on the scene.” Should it have been apparent that waiting in the hallway was unreasonable?

Yes. Indisputably yes.

Consider: The gunfire heard from inside the classroom was described as a “barrage” when the gunman first entered, but later became “sporadic” as officers assembled in the hallway. From this we may reasonably conclude, as the incident commander should have, that victims were being sporadically shot while he and his officers waited for a key to the door. The situation had not in fact transitioned from an active shooter to a barricaded suspect, but rather to one in which the shooter was merely less active than he had been. To wait outside under these circumstances in inexcusable.

I will grant that it is difficult to breach a door that opens outward, as most classroom doors do, but this means it was time for some creative thinking, which the school district police chief seems to have been incapable of. Judging from pictures of the school I’ve seen in news reports, there were windows that should have been considered as an alternate entryway. For that matter, in the time they waited, officers could have created an opening in the exterior wall with sledgehammers or cut a hole through the roof had they been directed to do so. Anything would have been preferable to waiting as long as they did.

Let the investigations unfold, and let the consequences fall where they may.

Some Classic Folding Blades

Mid size jack knives and stockman pattern, just right for opening mail, cutting string or slicing an apple for lunch. And no one worried or fretted when one was pulled out either. If one forgot their knife at home, another had theirs to lend out.

The Cost