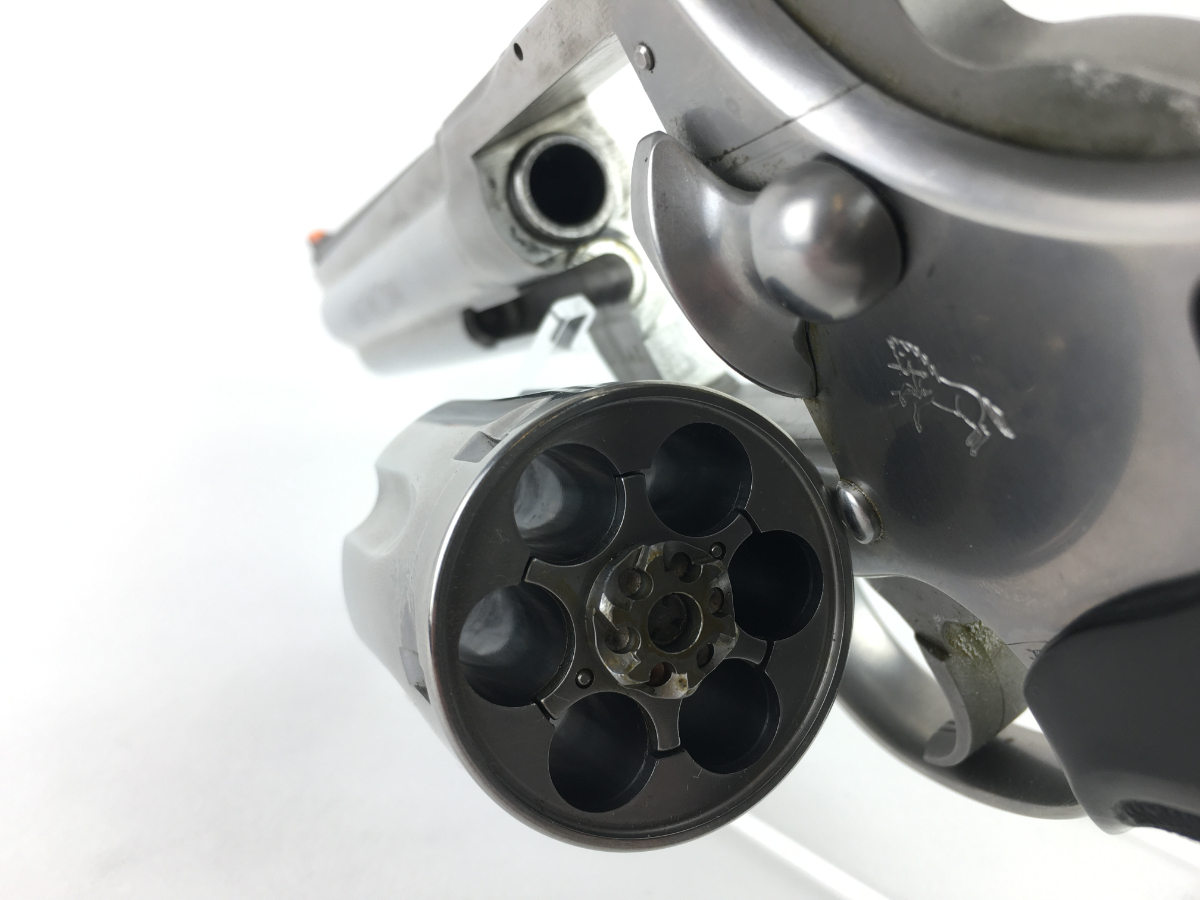

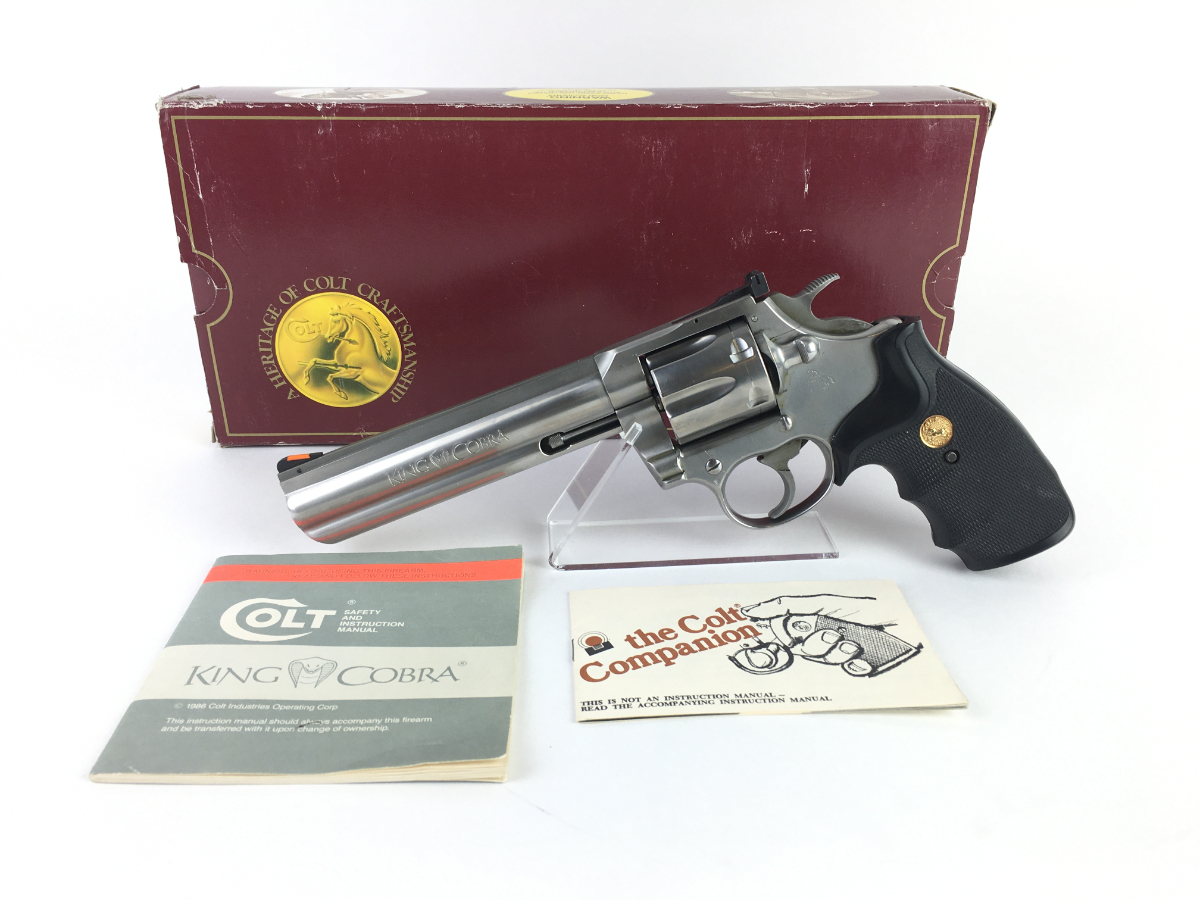

Gun: S&W .38/44 Heavy Duty Model of 1950

Caliber: .38 Spl./.38 Super Police/.38/44 High Velocity/.38/44 High Speed (Note: All Heavy Duty barrels were marked .38 Spl.)

Serial No: S897XX (Post War “S” prefix denotes hammer block safety)

Condition: 60 percent-NRA Good (Modern Gun Condition Standards)

Manufactured: 1953

Value: $450 to $570 (based on the recent auction price for the gun pictured)

Some guns particularly reflect the era in which they were made. That is certainly the case with the Smith & Wesson .38/44 Heavy Duty, a brawny handful of revolver based on the N-frame S&W 44 Spl. Hand Ejector Third Model (also known as the Model 1926), but fitted with a .38 Spl. cylinder and barrel.

This hard-shooting hybrid came about, indirectly, due to Prohibition, the resultant production of illicit whiskey, and the corresponding rise of organized crime. With the crash of the stock market in 1929 and the onset of the Great Depression, organized crime became even more rampant. As a result, law enforcement was finding its standard .38 Spl. revolvers, which fired a 158-grain, round-nose bullet with a muzzle velocity of 755 f.p.s., no match for mobsters or bandits wearing “bullet-proof” vests and driving steel-bodied cars. To answer the lawmen’s call for greater stopping power, S&W president Harold Wesson responded with what could be called the .38 Spl. +P of its day, a souped-up .38 Spl. that fired a 158-grain bullet with an increased muzzle velocity of 1175 f.p.s. and produced 460 feet-pounds. of energy at the muzzle, enough to punch through both sides of an automobile. Other .38/44 High Velocity bullet weights were soon commercially offered.

The .38/44 Heavy Duty was the only S&W revolver qualified to safely handle the new loads. It was introduced in 1930 with a fixed sight, 5-inch barrel, blued or nickeled finish, and walnut stocks, though 4- and 6½-inch barrel lengths were eventually offered. (A .38/44 Outdoorsman, sporting target sights and a 6½-inch barrel, was brought out in 1931.) Production of the .38/44 Heavy Duty was temporarily halted in 1941 and resumed in 1946. It became the Model of 1950 four years later, the Model 20 in 1957 and was finally discontinued in 1966, with a total post-war production of 20,604 revolvers.

The Heavy Duty Model of 1950 shown here was made in 1953 and features the post-war  “S” prefix serial number. It sports a proper, tapered barrel in the less-frequently encountered 4-inch length. Although mechanically sound, the “plum”-colored cylinder is an indication of either a refinish or an imperfection in bluing the chrome-nickel cylinder. Nonetheless, in NRA Good condition, this gun sold for $570 at on-line auction house Lock, Stock & Barrel a few months ago. By comparison, a .38/44 Heavy Duty, circa 1935, with 5-inch barrel in NRA Very Good condition, sold for $711 in that same auction.

“S” prefix serial number. It sports a proper, tapered barrel in the less-frequently encountered 4-inch length. Although mechanically sound, the “plum”-colored cylinder is an indication of either a refinish or an imperfection in bluing the chrome-nickel cylinder. Nonetheless, in NRA Good condition, this gun sold for $570 at on-line auction house Lock, Stock & Barrel a few months ago. By comparison, a .38/44 Heavy Duty, circa 1935, with 5-inch barrel in NRA Very Good condition, sold for $711 in that same auction.

(I am so sorry to have traded mine away for a M1a. As it was the better gun)

Politicians refer to themselves as public servants. Swamp creatures like Joe Biden will extol their many decades of employment in Washington DC as though they had been some kind of galley slave toiling away on an Athenian man o’ war. I have actually met a couple of those guys. Their idea of selfless service does not quite match my own.

American legislators spend money like drunken sailors. Actually, that’s not true. Drunken sailors couldn’t even begin to burn cash in as profligate a manner as might your typical freshman congressman. They’ve raised wasting money to an art form.

You think I’m kidding. Back when I was a soldier I spent a week as a local liaison officer for a group of congressmen on a fact-finding mission after the First Gulf War. It was amazing just watching them eat. They’d go to the nicest restaurant in town and order one of anything they might be curious about. Then they swapped plates around so everybody got a taste. One of my several duties was to scurry back and forth to the Officers’ Club cashing $500 government traveler’s checks to pay for it all. It was surreal.

Everybody in DC has sold their soul to somebody. I’ll champion the folks on my side of the aisle in the vain hope that they might someday just leave me the heck alone, but they are all irredeemably corrupt. The system perpetuates itself. It will never get better.

On May 31, 2002, Pat Tillman and his brother Kevin walked into a local recruiting office and enlisted in the US Army. Pat walked away from a $3.6 million professional football contract and Lord knows what else so he could serve his country in the immediate aftermath of 911. Pat Tillman’s story is that of a conflicted man and a horribly flawed system. However, his is a tale of epic sacrifice and genuine selfless service.

Pat Tillman was the eldest of three sons born to Patrick and Mary Tillman in Fremont, California. By NFL standards, Tillman was not a terribly big man. He stood 5’11” and weighed 202 pounds when dressed out as a safety for the Arizona Cardinals. Pat personified the axiom, “It’s not the size of the dog in the fight, it’s the size of the fight in the dog.”

In high school Tillman preferred baseball, but he failed to make the team as a freshman. At that point, he turned his attention to the gridiron. Throughout his childhood and adolescence, Pat was powerfully close to his friends and family. He married his childhood sweetheart just before he enlisted in the Army. He and his brother Kevin enlisted together, trained together, and were eventually both assigned to the 2d Ranger Battalion based at Fort Lewis, Washington.

Pat Tillman attended Arizona State University on a football scholarship and excelled as a linebacker. An exceptionally deep young man, Tillman was well read and made good grades. He maintained a 3.85 GPA in marketing and graduated in 3.5 years despite the rigors of starting on his college football team.

Pat thrived in the NFL. Sports Illustrated writer Paul Zimmerman named Tillman to the 2000 NFL All-Pro team based upon his stellar performance as a defensive player. He turned down a $9 million offer to move to the St. Louis Rams out of loyalty to his Arizona team.

Eight months after the 911 attacks and with the remainder of his 15 games completed from his 2001 contract, Pat Tillman left $3.6 million on the table to go to Army basic training alongside his brother. Pat’s brother Kevin gave up a burgeoning career in minor league baseball for the same path. These two men put their love of country ahead of the sorts of things the rest of us would just about kill for.

Appreciate the details here. I’m a happily married hetero man, and even I admit that Pat Tillman was an exceptionally good-looking guy. Intelligent, articulate, and well-educated, Tillman had the world by the tail. Once his time in the NFL was complete Pat Tillman could have easily parlayed his gifts and experiences into a career on television or in Hollywood. Instead, he opted for the Ranger Regiment.

I was an Army aviator, but I worked with those guys on occasion. Theirs was an absolutely miserable life. Junior enlisted soldiers don’t get paid beans, and the optempo in the Ranger Battalions is utterly grueling. In less than two years on active duty, Pat Tillman completed basic training and AIT as well as the Ranger Assessment and Selection Program. He was deployed to Iraq as part of Operation Iraqi Freedom in September of 2003 after which he attended Ranger School at Fort Benning. Once a fully tabbed Ranger, he returned to Second Bat at Lewis and deployed to Afghanistan where he was based at FOB Salerno.

Up until this point, Pat Tillman was the US Army’s poster child. An American superhero with a face right out of central casting, Tillman’s story could not have been any more compelling had it been drafted by an action novelist. Then Something Truly Horrible happened.

Combat is an ugly, filthy, chaotic thing. It is seldom as tidy or predictable as the movies and sand table exercises depict it to be. On April 22, 2004, the fog of war claimed a genuine American hero.

On a forgotten road leading from the Afghan village of Sperah about 40 klicks outside of Khost, Pat Tillman’s small HUMVEE-mounted patrol ran into trouble. Their mission that day was to retrieve a disabled HUMVEE. This tale is made all the more tragic in that we abandoned tens of thousands of these vehicles when we fled Afghanistan recently. The details are fiercely debated to this day, but here is the official description.

Tillman was in the lead vehicle designated Serial 1. Serial 1 passed through a mountainous pass and was roughly one kilometer ahead of Serial 2, the following HUMVEE. At that point, Serial 2 was purportedly engaged by hostile forces.

Upon hearing of the ambush, the Rangers in Serial 1 dismounted and made their way on foot back toward an overwatch position where they could provide supporting fires for Serial 2. In the resulting chaos, the Rangers of Serial 2 lost touch with the specific location of the lead Rangers. In the violent exchange of fire that followed Tillman’s Platoon Leader and his RTO (Radio Telephone Operator) were wounded. An allied member of the Afghan Militia Force was killed. Pat Tillman caught three 5.56mm rounds from an M249 SAW to the face from a range of 10 meters and died instantly.

First introduced in 1984, the Belgian-designed M249 Squad Automatic Weapon was an Americanized version of the FN Minimi. An open-bolt, gas-operated design, the M249 was conceived to provide the Infantry squad with a portable source of high-volume, belt-fed automatic fire. The M249 has seen action in every major military engagement since the US invasion of Panama in 1989.

The M249 weighs 17 pounds empty and 22 pounds with a basic load of 200 linked rounds. The weapon fires from an open bolt and features a quick-change barrel system. The gun will feed on either disintegrating linked belts or standard STANAG M4 magazines. In my experience, the magazine feed system was never terribly reliable.

USSOCOM adopted a lighter, more streamlined version of the M249 titled the Mk46 for use with special operations forces. The M4 magazine well, vehicle mounting lugs, and barrel change handle were all removed on the Mk 46 to save weight. The USMC has aggressively supplemented their rifle squads with the HK M27 Infantry Automatic Rifle in lieu of many of their SAWs. These weapons are currently issued at a ratio of 27 IARs and 6 SAWs per rifle company. The Next Generation Squad Weapon-Automatic Rifle program is tasked with finding a suitable replacement for the aging M249’s in the Army inventory.

What happened next was a blight on the US Army. To have Pat Tillman, the real live Captain America killed due to friendly fire in a botched combat operation was not the story the Army wanted pushed. As a result, several senior Army officers moved to massage the narrative and outright suppress the story to both the media and the Tillman family. The end result was an absolutely ghastly mess.

There were allegations that Tillman, by now disillusioned with the war in Iraq, was about to offer an interview with controversial activist Noam Chomsky upon his return from his Afghanistan deployment that would be critical of the Bush Administration. As Tillman’s death occurred in a crucial time leading up to the 2004 Presidential elections conspiracy theorists even proposed that he had been intentionally murdered. However, interviews with his fellow Rangers verified that Tillman was a popular and selfless member of the team. In the final analysis, it all seems to have been a truly horrible mistake. After several investigations undertaken by the military, three mid-level Army leaders purportedly received administrative punishment as a result.

A word on the conspiracies. Soldiers don’t fight for mom, apple pie, and America. They fight for each other. There’s just no way you could get a Ranger to intentionally shoot another Ranger to protect the reputation of a sitting President. This was simply a horrible accident.

The sordid circumstances surrounding the death of Pat Tillman in no way diminish the truly breathtaking scope of the man’s patriotism and sacrifice. Tillman was an avowed atheist throughout his life. After his funeral, his youngest brother Richard asserted, “Just make no mistake, he’d want me to say this: He’s not with God, he’s f&%ing dead, he’s not religious.” Richard added, “Thanks for your thoughts, but he’s f&%in’ dead.” It was an undeniably strange end for a genuine American hero.

Soldiers in combat will often pen a “just in case” letter to be opened in the event of their death. Pat’s note to his wife Marie said, “Through the years I’ve asked a great deal of you, therefore it should surprise you little that I have another favor to ask. I ask that you live.”

And live she did. Marie Tillman today is Chairman and Co-Founder of The Pat Tillman Foundation. This non-profit works to “unite and empower remarkable military service members, veterans, and spouses as the next generation of public and private sector leaders committed to service beyond self.” The Foundation has sponsored 635 Tillman Scholars and invested some $18 million in philanthropy. Marie has since remarried and is the mother of five children.

Even to the most disinterested, the Winchester lever-action’s very profile is recognizable, making it a true icon of the American West. What is not generally known is that Winchester lever-actions were, in their day, cutting-edge military rifles. And they proved effective combat arms from the American Civil War through World War I, despite the fact that they were never awarded a large U.S. military contract.

Even to the most disinterested, the Winchester lever-action’s very profile is recognizable, making it a true icon of the American West. What is not generally known is that Winchester lever-actions were, in their day, cutting-edge military rifles. And they proved effective combat arms from the American Civil War through World War I, despite the fact that they were never awarded a large U.S. military contract.

The earlier Winchester lever-actions (the Models 1866, 1873 and 1876) shared the Henry rifle’s toggle bolt system but offered Nelson King’s patented loading gate on the receiver’s right. Although durable and dependable, the toggle bolt could not handle loads more powerful than handgun cartridges. That became a limiting factor as cartridges, particularly military rifle cartridges, became more powerful during the 1870s. Ultimately, Winchester would turn to arms designer John M. Browning to overcome that shortcoming.

The first lever-action to bear the Winchester name, the Model 1866, was an improved version of the Henry rifle. The Model 1860 Henry was state-of-the-art technology—possessing rapid fire capability and generous magazine capacity—when used by Union soldiers during the American Civil War.

Often, warfare was observed and evaluated by officers from non-combatant nations who would then take note of the strategies and equipment used. The Civil War was observed by most European nations, but France and the Ottoman Empire took particular note of the Henry, and its successor, the Winchester Model 1866.

France was so impressed that its navy considered adopting the Winchester Model 1866. Rifle trials were conducted on the French frigate Semiramis in 1868. A report praised the Model 1866’s ability to fire quickly. The French navy planned to take advantage of the guns’ capabilities by placing them with sailors in crow’s nests (Babies dans les hunes) so as to lay rapid fire down on the decks of enemy ships. In February 1870, recommendations were made to adopt the Model 1866, designated by the French as the “Carabine Henry – Winchester.” The Franco-Prussian War (July 1870 to May 1871) interrupted its possible adoption, but the need for rifles created an opportunity for Winchester.

Although France did not officially adopt the Winchester Model 1866, several thousand were purchased during the Franco-Prussian War in a mad scramble to gather arms. France purchased 3,000 Model 1866 rifles with 16-round-capacity magazines and 3,000 with 13-round magazines; included with the purchase were 4.5 million rounds of .44 Henry ammunition. These were distributed to various units, including combat troops, and were the only foreign rifles to be retained for an extended period of time after the war. The Model 1866 became the standard rifle for the 630 gendarmes of the Corsican 17th Legion.

The Model 1866 was also purchased by the Ottoman Empire and used against the Imperial Russian Army in the Russo-Turkish War (1877 to 1878). The Ottomans purchased 45,000 muskets and 5,000 carbines in 1870 and 1871. A portion of those was used in 1877, during the Siege of Plevna. The Russian army suffered tremendous losses when it attacked the Ottomans, in part due to the use of the Winchester rifles.

Imperial Russia took note and began a search for a repeating rifle, which resulted in the development and adoption of the Mosin-Nagant years later. Still, the repeating firepower of the Winchester lever-action did not spur large military purchases, as Winchester lever-actions were more costly than single-shot and bolt-action rifles.

During the 1870s, single-shot breechloaders firing powerful cartridges dominated the military rifle market. That was demonstrated by the large quantity of single-shot Rolling Block rifles sold by the Remington Arms Co. around the world. The concept of a medium-powered cartridge being fired rapidly from a rifle with a large magazine was not embraced by most military leaders. Their belief was that common soldiers would waste ammunition if given repeating rifles and that Winchester repeating rifles were not robust enough and too complicated for military service. Even so, Winchester continued to develop the lever-action repeater with the designs of John Browning.

In keeping with the function of Winchester’s lever-actions, Browning designed a new action that was much stronger but retained the under-receiver lever and handling qualities that were hallmarks of earlier Winchesters. The new approach used vertical bolts that gave the new models the ability to fire more powerful cartridges.

The first Browning-designed lever-action was the Model 1886, followed by a smaller, lighter version, the Model 1892. The Model 1886 could handle the .45-70 Gov’t cartridge adopted by the U.S. Army, as well as similarly powerful chamberings. The Model 1892 was better-suited for revolver and lighter rifle cartridges. Even so, the introduction of smokeless powder in the 1880s made these blackpowder models virtually obsolete. Again, John Browning provided a solution.

With the advent of smokeless powder, Winchester offered the Browning-designed Models 1894 and 1895. The stronger receivers could handle the higher chamber pressures of smokeless powder. The Model 1895 was specifically designed with martial applications in mind. The receiver was made to handle military cartridges, and a box magazine was incorporated instead of the traditional tubular magazine. The gun was evaluated in 1895 at the New York National Guard rifle trials. Although the trials did not result in adoption, a number of rifles chambered in .30-40 Krag were purchased a few years later by the U.S. War Dept. for use in the Spanish-American War. Still, military acceptance and large orders of lever-action rifles would elude Winchester until the advent of the First World War.

The realities of World War I brought about a change of heart toward Winchester’s lever-actions.The Allies’ extreme shortages encouraged the purchase of large quantities of rifles from American manufacturers. Great Britain, France and Imperial Russia purchased Winchester lever-actions for frontline and secondary use. Many were “off the shelf” models, which included the Models 1886, 1892 and 1894. Some were ordered with specialized requirements. Contracts were signed for modified Model 1894 and Model 1895 rifles. The size of the purchases varied; the Model 1886 was the least-procured, while the Model 1895 accounted for the greatest numbers sold.

Great Britain

Great Britain purchased three different Winchester lever-action models: the Model 1886, Model 1892 and Model 1894. The first wartime purchase, by the Royal Flying Corps, was for fewer than 50 Model 1886 Winchesters chambered in .45-90 Win. Special cartridges were developed with incendiary bullets designed to ignite the hydrogen gas in German airships and balloons. The rifles allowed the Royal Flying Corps to counter this airborne threat while they were developing more effective arms.

To allow all standard-issue Lee-Enfield rifles to be available for the front, Winchester repeaters were also purchased by the Royal Navy, and they were used shipboard for guard duty and mine clearing, the details of which are unknown. The Royal Navy acquired 20,000 Model 1892 rifles in .44-40 Win. and approximately 5,000 Model 1894 carbines in .30 WCF (.30-30 Win.). Those Winchesters, along with some Remington Rolling Block rifles, were replaced in 1915.

France

In order to prioritize issue of the standard infantry rifle—the Model 1886 Lebel—to frontline troops, France turned to obsolete Gras Model 1874 rifles for service and support soldiers. Almost immediately, the French embarked on a program to convert blackpowder Gras rifles to the smokeless 8 mm Lebel cartridge. The conversion proved difficult, and progress was slow. Unable to produce enough standard-issue Lebel rifles or convert enough Gras rifles, France contracted with Winchester and Remington to arm rear-echelon soldiers. Remington was contracted for a modified version of its Rolling Block rifle, while Winchester received a contract for 15,100 Model 1894 carbines.

The contract required the addition of metric graduations to Winchester’s No.44A rear sight and the addition of sling swivels on the left side of the buttstock and barrel band. The sling swivels were specifically required so that the carbine could be carried en bandoulière (the French term for carrying a carbine across the back). These added features were unique to the French contract. The carbines were issued to motorcycle couriers, artillery troops and transport units. Model 1894s also found their way to balloon units, and some may have been used by airmen in their aircraft.

After the war, the French Winchester Model 1894s were sold by the French government to unknown buyers. Some bear Belgian proofmarks, as they were transferred through Belgium. The Belgian proofs have led many to incorrectly assume that those guns were purchased by the Belgian Congo.

Imperial Russia

Imperial Russia helped Winchester realize its largest military sales since the introduction of the lever-action rifle. A total of 300,000 Model 1895 rifles were ordered in two contracts, one in 1914 and another in 1915.

Known as the “Russian Musket,” this Model 1895 variant was adapted to fire the Russian rimmed 7.62×54 mm Model 1908 cartridge. The contracts required the addition of a bayonet lug and stripper-clip guides mounted on the receiver. The rifle had to accept the standard Russian Mosin-Nagant stripper clip and the rear sight needed to be graduated in Russian arshins. Those features made the Model 1895 the equal of any rifle on the battlefield. It saw the most use with frontline fighting units, and was issued to units formed in Russia’s western provinces of Finland, Poland and Latvia. Period photographs show large military formations of Imperial soldiers holding Model 1895 Russian Muskets. The surviving Model 1895 rifles were put in storage after the Russian Civil War.

The Spanish Civil War (1936-1939) and consequent arms embargo gave Joseph Stalin the opportunity to sell tons of arms, including obsolete rifles, in exchange for Spanish gold. The Model 1895 rifles were sold for many times over their original purchase price. The Russians shipped 9,000 Model 1895 rifles in 7.62×54 mm R on Oct. 25, 1936, to the Spanish Republicans. Another shipment of 9,000 Winchester rifles (various models and calibers) had been shipped days earlier.

Comparatively few Model 1895 Russian Muskets are found today. The few in collections typically exhibit heavy usage and often bear Spanish arsenal markings and signs of arsenal refinish.

The lever-action proved itself a worthy combat rifle from its first use in the American Civil War through to World War I. In every instance the results were more than satisfactory.

Period photographs courtesy of Commandant Philippe François, John Adams-Graf and Christophe Larribère