The Constitution contains a powerful set of ideals and a wise system of governance, based on a deep reading of classical and medieval history as well as Renaissance philosophy. However, none of this matters if no system of force is in place to keep and defend the Constitution.

Ultimately, this what the 2nd Amendment is about: A distributed capacity for violence guaranteed to private citizens so that they may serve as a check and balance on the power of the state.

America’s Founding Fathers understood an uncomfortable truth: Behind every law is the implicit threat of force, and behind every vote is the implicit threat of rebellion. Such a bargain is what holds a free society together. And no society with a wide power imbalance remains free for very long.

This truth was predicated upon the Founders classical education and their deep understanding of the power dynamics underpinning the systems of governance during the Roman Republic and Ancient Athens. The Roman Republic in particular influenced their views. Why? Because it provided not simply a template for government, but a historical warning about what can happen to a republic if precautions are not taken to ensure its survival.

Thus the Constitution intentionally contained concepts like separation of powers and a system of checks and balances. These concepts were predicated upon a core truth, as eloquently stated by Thomas Jefferson in the Declaration of Independence: ‘Governments are instituted among men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.’”

If you picture political power as a pyramid, the intention of the Founders was clear: The individual was paramount, having natural rights, and the individual would then delegate a portion of his or her political power to the state – hence, the state governed with the individual’s consent.

This delegation took place in stages in order to maintain as much decentralization as possible: First, the individual would delegate a portion of their political power to the municipality level. Then the municipal government would delegate a portion of its power to the county level. Then the counties would delegate a portion of their power to the state level. And ultimately the states would delegate a portion of their power to the federal level.

This delegation is best reflected in the Bill of Rights’ 10th Amendment to the Constitution: “The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.”

Underpinning all of this tiered, sequential delegation was an uncomfortable, yet necessary, truth: That the individual must retain an implied threat of force against the state, and that this threat must be credible, in order to stop the state from deviating beyond the consent given to it or otherwise overrun the individual’s natural rights – what we’d refer to nowadays as a “power grab.”

But what happens when the state’s power grows so vast that individuals cannot resist it whatsoever? That they cannot provide a credible, implied threat of force to counterbalance state power because the state’s weapons have become so devastating? When the state no longer has the consent of the governed, and instead has intimidated the governed into submission?

This is a look at political power and how it has changed as weapons technology has advanced, from Ancient Athens and their virtuous citizen-hopline-freeholder, through the Middle Ages and armored knights, up to our modern weapons of war such as drones and atomic weapons. The concurrent centralization of power, finance, and the capacity to commit meaningful violence is no accident.

But how and why did this happen? And is there any way that we can play the tape backward to regain what we have lost?

A Centralized Capacity for Violence

When people talk about the atom bomb as a trump card for home-grown revolution, they’re really talking about the centralized capacity for violence.

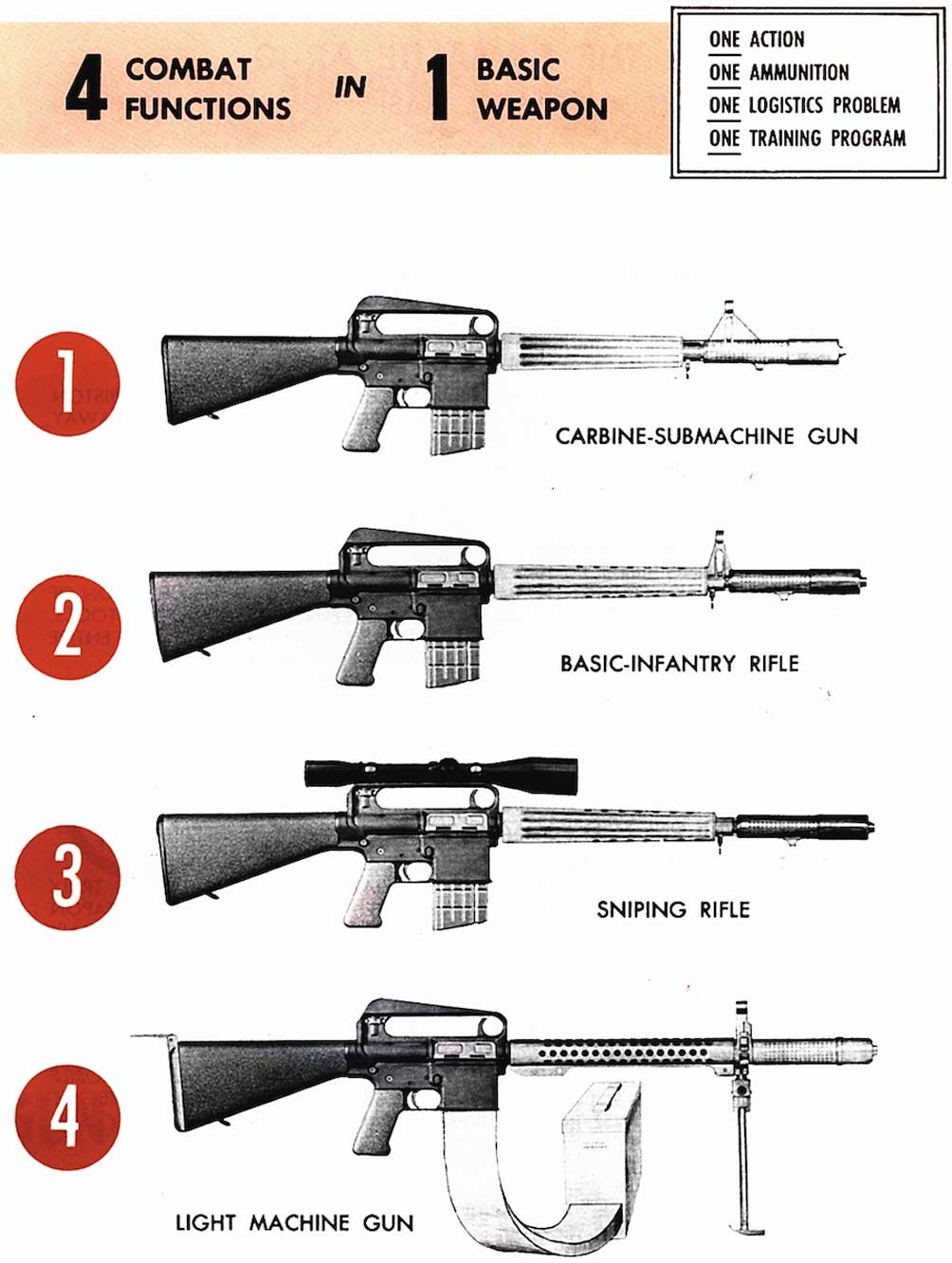

The bomb could be anything as it is simply a stand-in for the average man’s recognition of the American military’s phenomenally powerful weapons; weapons in a totally different class than even a fully automatic battle rifle or rudimentary ballistics like TNT.

Atomic weapons are measured in kilotons of TNT – the best our brains can capture the awe and might of the bomb.

It’s a small example, but cuts to the heart of centralized capacity for violence: The increased ability of smaller and smaller groups of men to do greater and greater amounts of damage. In the case of the atomic bomb, the ability of a single man to wipe out millions with the push of a button. This capacity is not limited to just the bomb.

The military is smaller and thus relies on a lighter, more agile, and efficient infantry than it once did. Only one or two men are needed to wipe a city from a map. Compare with an infantry platoon of 27 men. As bombs became bigger, military technology became much more accurate and capable of hitting one specific thing (say, a Sudanese aspirin factory versus a small, neutral village).

America’s nuclear arsenal is the apotheosis of centralized force, giving a single man the ability to kill everyone on earth many times over.

But it is not hyperbole to say our current military technologies are Godlike, even disregarding the bomb. Entire regions can be wiped from the map at the push of a button, and it only takes one man to push that button. Compare with the mounted cavalry of old.

Not to belabor the point, but the term “bomb” fails to capture the magnitude of what a bomb can do. The atomic bomb is like dropping a small sun onto a city. It is ghastly and terrifying, and may mark man’s first true foray into “secrets man was not meant to know.”

In addition to being more precise, violence is much easier to distribute from afar. For context, during the Second World War, carpet bombing was developed because it was so hard to get a single bomb to hit anything, even when you were just a few thousand feet from the target. Now someone on the other side of the planet can send a missile into a cave and navigate the tunnels inside.

This happens at the micro-level as well. Think about the small-town sheriff who, for some reason, has a battle-ready tank. On one level, it’s laughable, the militarization of the police reduced to its most ridiculous cliche. But on another, perhaps more important level, it’s a demonstration of the centralization of capacity to commit force at the local level. The average police department is equipped like a small infantry squad with light tank support.

A well-armed home has a handful of long arms and pistols, with precious little training in things like small squad tactics. Our personal fortresses are anything but secure against the state.

Distributed Violence and Power in Ancient Greece

We think of Ancient Greece as a democracy, and indeed, it was, but its democratic polities were far from egalitarian. Its democratic society was made possible by the hoplite system.

The hoplite was the basic infantry soldier of ancient Athens and other Greek city states. To be a hoplite meant to supply one’s own arms. To supply one’s own arms was only possible for free landholders. Full citizenship was accorded only to men with a full set of gear. Men with only partially complete sets held lower rank, in the military and in society in general.

Hoplites made ancient Greek democracy possible.

Indeed, there is great wisdom to how the Greeks granted citizenship: the benefits of citizenry imply a responsibility to defend the polity. Those incapable of putting up a meaningful fight against invaders (or in the case of Sparta, constant helot rebellions) did not enjoy the full fruits of Greek citizenship.

Ancient Greece was a far more equitable society than its contemporaries because the citizenry were landed men with skin in the game. They couldn’t simply take off for the nearest convenient city. They defended their democratic society — and their land — with their lives.

Decision-making included everyone who was going to fight. No one man held much power relative to others except for his ability to command larger groups of men through legitimately earned leadership and authority.

This isn’t an endorsement of turning America into Starship Troopers, but we should contrast the capacity of the Greek hoplites to commit meaningful violence against the rulers and their neighbors against the feudal system of serfs, lords and mounted cavalry emerged in the fallout after the collapse of the Roman Empire.

We tend to think of medieval lords as holding power due to accidents of birth, but they held civilization together while Rome fell. Their titles, such as duke and marquis, were military titles, implying a duty of military service to their lord and the king. The difference between these medieval lords and the free hoplites of classical antiquity is that the medieval world allowed much smaller groups of men to commit far greater levels of violence. This centralized capacity for violence.

Serfs were drafted, oftentimes reluctantly, when additional forces were needed, mostly for the pure weight of the meat. The medieval world had many peasant rebellions but peasants were, to put it bluntly, useless against men in armor on horseback with crossbows, lances, and strong martial culture.

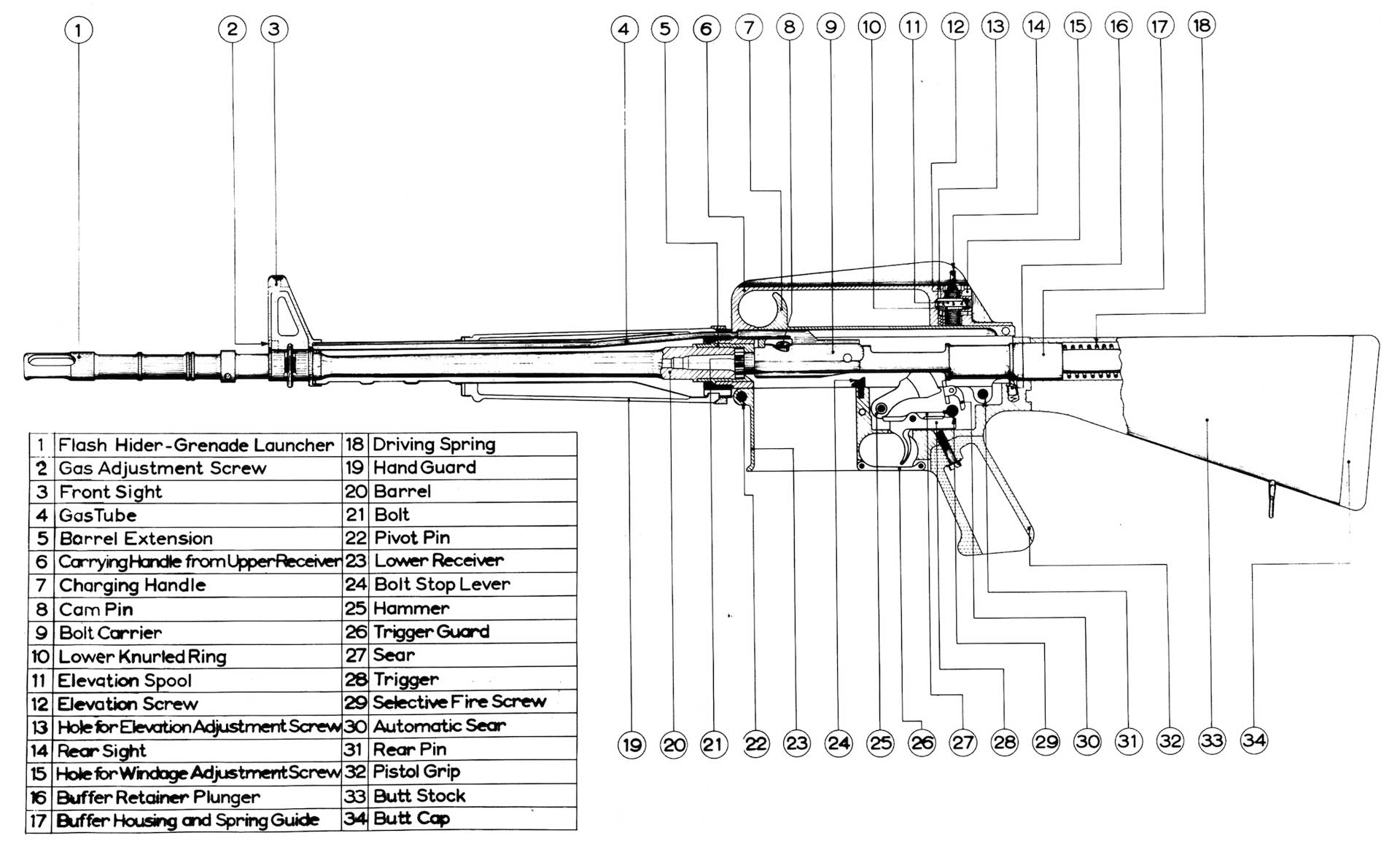

The average Athenian didn’t have the means for a full hoplite spread, and thus full military service and citizenship. Still, men with only partial kit could do quite a lot, militarily. Thus their input was needed for democratic consensus. But the middle ages saw a greater contraction of the martial caste, due to revolutionary developments in weapons technology.

It took only the humble stirrup to radically alter the distribution of military power in Europe. Previously, men on horseback were simply mounted infantry, not true cavalry. They dismounted to fight. Now they no longer had to. They could attack at speed on horseback, allowing for heavier armor to be worn and heavier weapons to be used.

Fewer men could do more with less. A partial suit of armor and a short sword was worthless against true cavalry armed with broadswords, lances, and crossbows – the Sherman tanks of their day. This revolution in military technology meant that the more democratic society of ancient Greece and the Roman Republic were now impossible.

Far more wealth was needed to obtain a meaningful capacity to commit violence. The smaller group of men with the means to purchase such were also able to commit far greater levels of violence with far fewer numbers.

You are here.

Modern Revolutions in Distributed Violence

It’s important to note that the centralization of capacity for violence is predicated on the accuracy of weapons. Old school ballistics weren’t the most accurate thing in the world. Two armies could stand on either side of a field, shooting all day. Any kill shots they got were entirely coincidental because muskets weren’t that accurate, hence the need for large formations of men.

Then something changed: Rifling. Gunsmiths learned that by putting grooves inside of a barrel, the accuracy of a weapon dramatically increased. The American Civil War was a bloodbath in part due to the development of the Springfield Model 1861. While wildly inaccurate by modern standards, it was revolutionary at the time in terms of converting the implied threat of violence into a very real promise of death.

The nobility hated firearms because one didn’t need to learn how to use a broadsword to knock off a king. All one had to do was get close enough, point, and shoot. The ability to commit meaningful violence moved from the exclusive province of the military caste to anyone who could get their hands on a gun.

When bombs were developed, they followed a similar trajectory in terms of destructive power. Even as late as World War II, bombs were so inaccurate that German intelligence couldn’t figure out what the British were trying to blow up. Carpet bombing was developed as a way to offset this inaccuracy, an aerial counterpart to the mass formations of pre-rifling musketeer troop formations.

The Springfield 1861 wasn’t the end of firearms development. Nor were the first rudimentary aerial bombs the end of heavy ballistic development. Everyone knows about the arms race with regard to atomic weaponry. Less known is the development of conventional bombs that can actually hit their targets with reliable accuracy. Guided-missile systems were to heavy ballistics what rifling was to long arms.

Between 1967 and 1973, guided-missile systems were developed and proved to be orders of magnitude more accurate in hitting their targets. The clunky, inaccurate bombs requiring a score of men to deploy were replaced with precise systems requiring only one or two men.

It’s often said that during the Great War it took 10,000 rounds to kill a single man. Now one or two missiles could obliterate entire sections of a city. Ten thousand to one are some pretty long odds, but two to one or one to one odds are a virtual certainty. Guided-missile systems don’t kill a single man like the apocryphal 10,000 rounds, they can flatten a military compound, city block, or an entire city. While significantly more expensive, their efficacy makes them a cost-effective investment for the military-industrial complex.

One simple example demonstrates the dramatic increase in the ability of the state to commit violence. Remember how we said British bombs were so useless that the Germans couldn’t even identify the intended target? 50 years later during Desert Storm in 1991, a cruise missile fired from a ship could enter a building through a specific window on a specific floor and hit a specific target inside that building, changing direction at the will of the operator.

This is important because the state is violence.

At the end of the day, the state is a means of coercion. Coercion relies upon the meaningful threat of violence. With the advent of advanced weapons systems, this threat of violence has been transformed from a mostly idle threat requiring a massive investment of human capital to a near certainty of death.

Conversely, the democratic process provides a means for the populace to express their dissatisfaction with the state. This is an implied threat of revolution, however, now the state has weaponry that can hit you where you live in a single shot while leaving every last building around you standing. The masses have, at best, only long arms at their disposal.

This is a power imbalance that cannot be ignored.

The promise of real violence trumps the empty threat of revolution. It’s certainly true that the United States military has been defeated by much smaller and more poorly equipped forces.

However, none of these small, primarily guerrilla forces – the Vietcong, the Taliban, or similar – presented the threat to American hegemony that a restive domestic population would if roused to rebellion.

This massive power imbalance is not the end of the story, as such situations have arisen in the past.

Consider the citizen-soldier of ancient Greece, whose broad forms endured until the end of Rome. This gave way to the aforementioned mounted knight, who had armor, lances, crossbows, and longswords – the advanced weapons systems of the time. They could run roughshod over peasant populations armed with little more than farm tools. In turn, the mounted knight was dethroned by the development of gunpowder, which dramatically leveled the playing field.

It is no coincidence that the development of gunpowder and effective firearms coincided, roughly speaking, with the rise of the democratic republic. No longer could the nobility simply say “let them eat cake.” Ignoring popular sentiment came with serious consequences.

What technology will mankind develop that will level the playing field today?

It’s hard to say, but futuristic developments like powered armor, cyberwarfare, and fourth generational warfare provide a glimpse as to how technology can be leveraged to put a thumb on the scale and bring the capacity to commit meaningful violence back into balance.

Until the pendulum swings back, however, the disparity in the ability to commit meaningful violence is a problem for human freedom that cannot be ignored. Guerrilla insurrections against the American empire in far-flung Third World provinces simply are not comparable to an uprising in the imperial core — the American homeland.

Will America Strike Its Own Citizens?

America has a long history of not using the atomic bomb so we often forget that America is the only country to have actually used them. So why hasn’t America used them in so long and would they use them again?

America has never had a “no first strike” policy and remains ambiguous about what situations would cause it to use nuclear weapons. It’s difficult, but not impossible, to imagine an American first strike during the Cold War, but it is far more difficult to imagine today. Who would America nuke?

How about Des Moines? Or Morgantown? Or Dallas? Americans are in a precarious position with regard to their own government. America has an empire, but the empire hates the Americans – largely using them as tax serfs to fund failed social programs at home and failed wars of choice overseas. If anything, the American people are an obstacle to the aims of the American Empire.

The American citizenry is one thing most of the rest of the world isn’t: A threat to the American empire. The massive reaction by globalist elites to Donald Trump shows just how particularly thin-skinned they are about peasant rebellions at home. And constant attacks on Second Amendment have failed to disarm the American middle class.

It is instructive to compare the United States to Australia and Canada in the time of COVID: The latter two are among the most repressive medical regimes in the world. America remains relatively free. The capacity for meaningful force, ownership of the reigns of power, and ownership of capital remains more distributed here – and our rulers know it. They know there is only so far they can go.

But maybe the global elites don’t need such stern measures against American citizens. The story of 2020 was largely that of concentrated attacks on the American middle class in the form of COVID lockdowns and riots aimed at immiserating and terrorizing them. COVID lockdowns attacked small businesses and “non-essential” workers in one of the biggest wealth transfers in human history. The riots likewise terrorized average Americans into a state of shock and silence.

The foot soldiers of the elites can do anything they want to you. Raising your hand against them, however, comes with extreme consequences. This is another example of the centralization of force, not using the military or armaments, but economic leverage and an asymmetrical application of the courts — anarchy for them, tyranny for you.

And who needs nukes when you’re ruling over a nation of renter-class serfs? The elites wouldn’t need anything approaching nuclear weapons to keep in line a population who own nothing and are totally reliant upon government handouts. This is the aim of the attacks on small businesses and the War on the Suburbs.

Perhaps the model for the future is not the totalitarian regimes of the 20th Century, but the feudal estates of the middle ages – now armed with intrusive surveillance technologies and Godlike military hardware.

Remember: The Constitution means nothing without the means to protect and defend it.

Regardless, until the scales are rebalanced, America will look less and less like the democratic republic we were all raised in over the years. The Founders simply did not design their system for a mass of effectively unarmed debt peons. The system is ripe for the taking by anyone with enough political will.

The problem of a highly centralized capacity to commit meaningful violence is structural. There are no clear solutions. A revolution in military technology is needed to rebalance the scales. In the meantime, however, each man can do his part to carve out a small fortress in defense of liberty, keeping the flame of liberty alive in our homes and our communities.

There are alternatives to this kind of serfdom, however, that don’t require waiting for the development of power armor or another leveling development in military technology. Above all, it is important to make oneself as antifragile as possible which means accumulating valuable skills, having multiple revenue streams, and, above all, hoping for the best while preparing for the worst.

Such moves towards greater resiliency in the face of overwhelming state military power and centralized force do not just protect you and yours. They provide a small, but important bulwark against tyranny, reasserting the implied threat of rebellion.

Unfortunately, an American Renaissance is reliant upon a dramatic shift in military technology rendering all current advanced weapons technology moot. No single man or even group of men can simply will such a situation into being.

The price of liberty, as is often said, is eternal vigilance. We need this kind of vigilance more than ever. Objective forces of economic reality and military innovation mean freedom in America and the West is hanging off the precipice. While we can never simply “play the tape backward,” we can move through our current state of centralization to a new decentralization, appropriate for our own time and place.