British Land Pattern Musket

a.k.a. Brown Bess |

A Short Land Pattern Musket

|

| Type |

Musket |

| Place of origin |

Kingdom of Great Britain |

| Service history |

| In service |

British Army 1722–1838 |

| Used by |

British Empire, Various Native American tribes, United States, Sweden, Mexico, Empire of Brazil, Zulu Kingdom |

| Wars |

Indian Wars, Maroon Wars, Dummer’s War, War of the Austrian Succession, Jacobite rising of 1745, Carnatic Wars, Seven Years’ War, Anglo-Mysore Wars, Anglo-Maratha Wars, American Revolutionary War, Xhosa Wars, British Colonisation of Australia, Haitian Revolution, French Revolutionary Wars, Kandyan Wars, Irish Rebellion of 1798, Napoleonic Wars, Temne War, Emmet’s Insurrection, British Expedition to Ceylon, Ashanti-Fante War, Musket Wars, Ga-Fante War, War of 1812, Greek War of Independence, Anglo-Ashanti Wars, Anglo-Burmese Wars, Baptist war, Texas Revolution(limited), Rebellions of 1837, Mexican-American War, Indian Rebellion of 1857, American Civil War (limited), Paraguayan War, Anglo-Zulu War |

| Production history |

| Designed |

1722 |

| Produced |

1722–1860s (all variants) |

| Variants |

Long Land Pattern, Short Land Pattern, Sea Service Pattern, India Pattern, New Land Pattern, New Light Infantry Land Pattern Cavalry Carbine |

| Specifications |

| Weight |

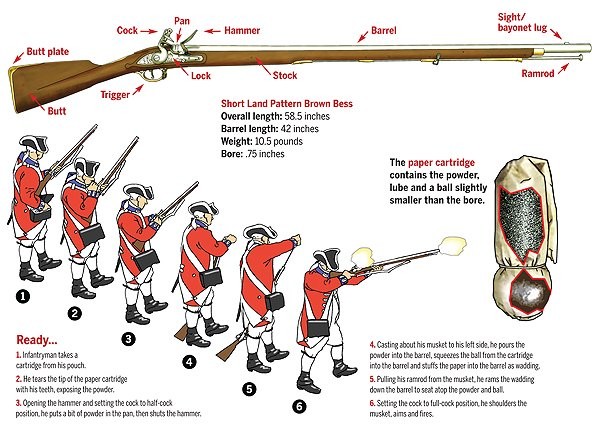

10.5 pounds (4.8 kg) |

| Length |

58.5 inches (149 cm) |

| Barrel length |

42 inches (110 cm) – 46 inches (120 cm) |

|

| Cartridge |

0.69 inches (18 mm) musket ball, undersized to reduce the effects of powder fouling |

| Action |

Flintlock |

| Rate of fire |

User dependent; usually 3 to 4 rounds every 1 minute. |

| Muzzle velocity |

Variable |

| Effective firing range |

Variable (50–100 yards) |

| Feed system |

Muzzle-loaded |

“Brown Bess” is a nickname of uncertain origin for the British Army‘s muzzle-loading smoothbore Land Pattern Musket and its derivatives.

This musket was used in the era of the expansion of the British Empire and acquired symbolic importance at least as significant as its physical importance.

It was in use for over a hundred years with many incremental changes in its design. These versions include the Long Land Pattern, the Short Land Pattern, the India Pattern, the New Land Pattern Musket and the Sea Service Musket.

The Long Land Pattern musket and its derivatives, all .75 caliberflintlock muskets, were the standard long guns of the British Empire‘s land forces from 1722 until 1838, when they were superseded by a percussion cap smoothbore musket.

The British Ordnance System converted many flintlocks into the new percussion system known as the Pattern 1839 Musket. A fire in 1841 at the Tower of London destroyed many muskets before they could be converted. Still, the Brown Bess saw service until the middle of the nineteenth century.

Most male citizens of the American Colonies were required by law to own arms and ammunition for militia duty.[1] The Long Land Pattern was a common firearm in use by both sides in the American War of Independence.[2]

In 1808 during the age of Napoleon, the United Kingdom subsidised Sweden in various ways as the British anxiously wanted to keep an ally in the Baltic Sea area, among other things deliverances of war material and with those, significant numbers of Brown Bess muskets for use in the Finnish War.[3]

During the Musket Wars (1820s–30s), Māori warriors used Brown Besses, having purchased them from European traders at the time.

Some muskets were sold to the Mexican Army, which used them during the Texas Revolution of 1836 and the Mexican-American Warof 1846 to 1848.

Brown Besses saw service in the First Opium War and during the Indian rebellion of 1857. Zulu warriors, who had also purchased them from European traders, used them during the Anglo-Zulu War in 1879.

One was even used in the Battle of Shiloh in 1862.[4]

Origins of the name

One hypothesis is that the “Brown Bess” was named after Elizabeth I of England, but this lacks support.

It is not believed that this name was used contemporaneously with the early Long Pattern Land musket but that the name arose in late years of the 18th century when the Short Pattern and India Pattern were in wide use.

Early uses of the term include the newspaper, the Connecticut Courant in April 1771, which said “… but if you are afraid of the sea, take Brown Bess on your shoulder and march.”

This familiar use indicates widespread use of the term by that time. The 1785 Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue, a contemporary work that defined vernacular and slang terms, contained this entry: “Brown Bess:

A soldier’s firelock. To hug Brown Bess; to carry a firelock, or serve as a private soldier.” Military and government records of the time do not use this poetical name but refer to firelocks, flintlock, muskets or by the weapon’s model designations.

Popular explanations of the use of the word “Brown” include that it was a reference to either the colour of the walnut stocks, or to the characteristic brown colour that was produced by russeting, an early form of metal treatment.

Others argue that mass-produced weapons of the time were coated in brown varnish on metal parts as a rust preventative and on wood as a sealer (or in the case of unscrupulous contractors, to disguise inferior or non-regulation types of wood).

However, the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) notes that “browning” was only introduced in the early 19th century, well after the term had come into general use.[citation needed] [here the author confuses simple varnishing with the browning of metal, two entirely different things]

Similarly, the word “Bess” is commonly held to either derive from the word arquebus or blunderbuss (predecessors of the musket) or to be a reference to Elizabeth I, possibly given to commemorate her death.

The OED has citations for “brown musket” dating back to the early 18th century that refer to the same weapon. Another suggestion is that the name is simply the counterpart to the earlier Brown Bill.

However, the origin of the name may be much simpler, if vulgar.

In the days of lace-ruffles, perukes, and brocade

Brown Bess was a partner whom none could despise –

An out-spoken, flinty-lipped, brazen-faced jade,

With a habit of looking men straight in the eyes –

At Blenheim and Ramillies, fops would confess

They were pierced to the heart by the charms of Brown Bess.

Kipling’s poem most possibly “hits the mark” although he may have based his poem on an earlier but similar “Brown Bess” poem published “Flights of Fancy (No. 16) in 1792.

Of course, the name could have been initially inspired by the older term of the “Brown Bill” and perhaps the barrels were originally varnished brown.

But it is well known in literary circles that the name “Brown Bess” during the period in question in the 17th to early 19th centuries is not a reference to a color or a weapon but to simply refer to a wanton prostitute [or harlot].[5]

Such a nickname would have been a delight to the soldiers of the era who were from the lower classes of English and then British society.

So far, the earliest use noted so far of the term “Brown Bess” was in a 1631 publication, John Done’s “POLYDORON: OR A Mescellania of Mo∣rall, Philosophicall, and Theologicall Sen∣tences.” at Page 152:

Things profferd and easie to come by, diminish them∣selves in reputation & price: for how full of pangs and dotage is a wayling lover, for it may bee some browne bes∣sie? But let a beautie fall a weeping, overpressed with the sicke passion; she favours in our thoughts, something Turnbull.

The Land Pattern Muskets

The Long Land Pattern “Brown Bess” musket was the British infantryman’s basic arm from about 1740 until the 1830s.

From the 17th century to the early years of the 18th century, most nations did not specify standards for military firearms. Firearms were individually procured by officers or regiments as late as 1745, and were often custom-made to the tastes of the purchaser.

As the firearm gained ascendancy on the battlefield, this lack of standardisation led to increasing difficulties in the supply of ammunition and repair materials.

To address these difficulties, armies began to adopt standardised “patterns”.

A military service selected a “pattern musket” to be stored in a “pattern room”. There it served as a reference for arms makers, who could make comparisons and take measurements to ensure that their products matched the standard.

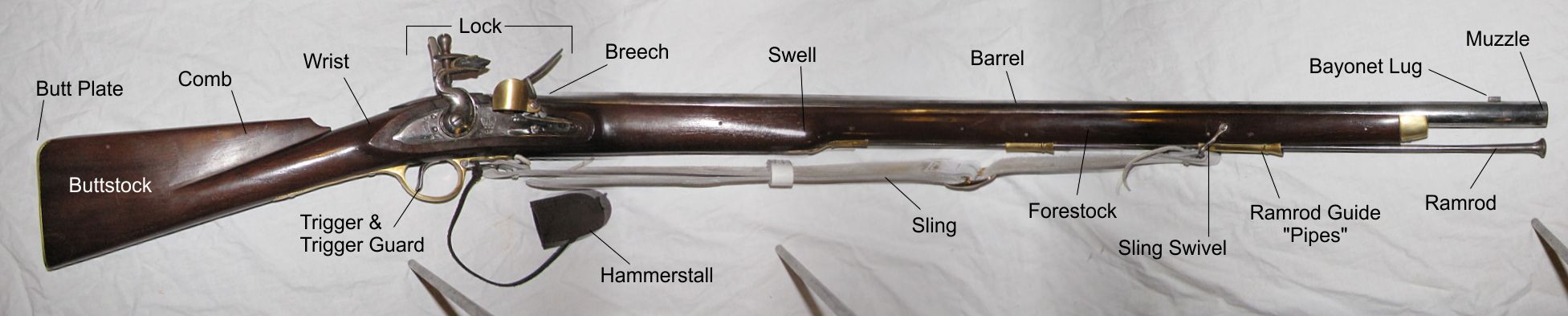

Stress-bearing parts of the Brown Bess, such as the barrel, lockwork, and sling-swivels, were customarily made of iron, while other furniture pieces such as the butt plate, trigger guard and ramrod pipe were found in both iron and brass.

It weighed around 10 pounds (4.5 kg) and it could be fitted with a 17 inches (430 mm) triangular cross-section bayonet. The weapon did not have sights, though it could be aimed using the bayonet lug as a crude sight.

The earliest models had iron fittings, but these were replaced by brass in models built after 1736.

Wooden ramrods were used with the first guns but were replaced by iron ones, although guns with wooden ramrods were still issued to troops on American service until 1765 and later to loyalist units in the American Revolution.

Wooden ramrods were also used in the Dragoon version produced from 1744–71 for Navy and Marine use.

The accuracy of the Brown Bess was fair, as with most other muskets.

The effective range is often quoted as 175 yards (160 m), but the Brown Bess was often fired en masse at 50 yards (46 m) to inflict the greatest damage upon the enemy.

Military tactics of the period stressed mass volleys and massed bayonet charges, instead of individual marksmanship.

The large soft projectile could inflict a great deal of damage when it hit and the great length of the weapon allowed longer reach in bayonet engagements.

As with all similar smooth bore muskets, it is possible to improve the accuracy of the weapon by using musket balls that fit more tightly into the barrel.

The black powder would quickly foul the barrel, making it more and more difficult to reload a tighter-fitting round after each shot and increasing the risk of the round jamming in the barrel during loading.

Since tactics at the time favoured close range battles and speed over accuracy, smaller and more loosely fitting musket balls were much more commonly used. The Brown Bess had a barrel bore of .75 caliber, and the typical round used was around .69 caliber.

While the looser-fitting musket ball reduced the effective range of a single musketeer firing at a single man-sized target to around 50 yards (46 m) to 75 yards (69 m), the Brown Bess was rarely used in single combat.

Since individual soldiers are not aimed for en masse volleys, the effective range of the Brown Bess when fired en masse was easily 100 yards (91 m) or more.

Standard European targets included strips of cloth 50 yards long to represent an opposing line of infantry, with the target height being six feet for infantry and eight feet, three inches for cavalry.

Estimations of hit probability at 175 yards could be as high as 75 percent in volley fire. This, however, was without allowances for the gaps between the soldiers in an opposing line, for overly tall targets or the confusing and distracting realities of the battlefield.

Modern testers shooting from rigid rests, using optimum loads and fast priming powder, report groups of circa five inches at fifty yards.[6]

Variations

X-ray of a Brown Bess musket recovered by LAMP archaeologists from an American Revolutionary War era shipwreck lost in December 1782.

It is believed to be a 1769 Short Land Pattern, and is loaded with

buck and ball.

Many variations and modifications of the standard pattern musket were created over its long history. The earliest version was the Long Land Pattern of 1722, a 62-inch (160 cm) long (without bayonet) and with a 46-inch (120 cm) barrel.

It was later found that shortening the barrel did not detract from accuracy but made handling easier, giving rise to the Militia (or Marine) Pattern of 1756 and the Short Land Pattern of 1768, which both had a 42-inch (110 cm) barrel.

Another version with a 39-inch (99 cm) barrel was first manufactured for the British East India Company, and was eventually adopted by the British Army in 1790 as the India Pattern.

Towards the end of the life of the weapon, there was a change in the system of ignition.

The flintlock mechanism, which was prone to misfiring, especially in wet weather, was replaced by the more reliable percussion cap.

The last flintlock pattern manufactured was selected for conversion to the new system as the Pattern 1839.

A fire at the Tower of London destroyed large stocks of these in 1841, so a new Pattern 1842 musket was manufactured.

These remained in service until the outbreak of the Crimean War when they were replaced by the Minie and the P53 Enfield rifled musket.

| Pattern |

Picture |

In service |

Barrel Length |

Overall Length |

Weight |

| Long Land Pattern |

|

1722–93

standard Infantry Musket 1722–68

(supplemented by Short Land Pattern from 1768) |

46-inch (120 cm) |

62.5-inch (159 cm) |

10.4 pounds (4.7 kg) |

| Short Land Pattern |

|

1740–97

1740 (Dragoons)

1768 (Infantry)

standard Infantry Musket 1793–97 |

42-inch (110 cm) |

58.5-inch (149 cm) |

10.5 pounds (4.8 kg) |

| India Pattern |

|

1797–1854

standard Infantry Musket 1797–1854

(Some in use pre-1797 purchased from the East India Company for use in Egypt) |

39-inch (99 cm) |

55.25-inch (140.3 cm) |

9.68 pounds (4.39 kg) |

| New Land Pattern |

|

1802–54

Issued only to the Foot Guards and 4th Regiment of Foot |

39-inch (99 cm) |

55.5-inch (141 cm) |

10.06 pounds (4.56 kg) |

| New Light Infantry Land Pattern |

The detail differences between this musket and the standard New Land Pattern were a scrolled trigger guard similar to that of the Baker Rifleexcept more rounded, a browned barrel and a notch back-sight, the bayonet lug being used as the fore-sight. |

1811–54

Issued only to the 43rd, 51st, 52nd, 68th, 71st and 85th Light Infantry and the Battalions of the 60th Foot not armed with rifles |

39-inch (99 cm) |

55.5-inch (141 cm) |

10.06 pounds (4.56 kg) |

| Cavalry Carbine |

|

1796–1838

Issued to cavalry units |

26-inch (66 cm) |

42.5-inch (108 cm) |

7.37 pounds (3.34 kg) |

| Sea Service Pattern |

|

1778–1854

Issued to Royal Navy ships, drawn by men as required, Marines used Sea Service weapons when deployed as part of a ship’s company but were issued India Pattern weapons when serving ashore |

37-inch (94 cm) |

53.5-inch (136 cm) |

9.00 pounds (4.08 kg) |

British Land Pattern Musket

a.k.a. Brown Bess |

A Short Land Pattern Musket

|

| Type |

Musket |

| Place of origin |

Kingdom of Great Britain |

| Service history |

| In service |

British Army 1722–1838 |

| Used by |

British Empire, Various Native American tribes, United States, Sweden, Mexico, Empire of Brazil, Zulu Kingdom |

| Wars |

Indian Wars, Maroon Wars, Dummer’s War, War of the Austrian Succession, Jacobite rising of 1745, Carnatic Wars, Seven Years’ War, Anglo-Mysore Wars, Anglo-Maratha Wars, American Revolutionary War, Xhosa Wars, British Colonisation of Australia, Haitian Revolution, French Revolutionary Wars, Kandyan Wars, Irish Rebellion of 1798, Napoleonic Wars, Temne War, Emmet’s Insurrection, British Expedition to Ceylon, Ashanti-Fante War, Musket Wars, Ga-Fante War, War of 1812, Greek War of Independence, Anglo-Ashanti Wars, Anglo-Burmese Wars, Baptist war, Texas Revolution(limited), Rebellions of 1837, Mexican-American War, Indian Rebellion of 1857, American Civil War (limited), Paraguayan War, Anglo-Zulu War |

| Production history |

| Designed |

1722 |

| Produced |

1722–1860s (all variants) |

| Variants |

Long Land Pattern, Short Land Pattern, Sea Service Pattern, India Pattern, New Land Pattern, New Light Infantry Land Pattern Cavalry Carbine |

| Specifications |

| Weight |

10.5 pounds (4.8 kg) |

| Length |

58.5 inches (149 cm) |

| Barrel length |

42 inches (110 cm) – 46 inches (120 cm) |

|

| Cartridge |

0.69 inches (18 mm) musket ball, undersized to reduce the effects of powder fouling |

| Action |

Flintlock |

| Rate of fire |

User dependent; usually 3 to 4 rounds every 1 minute. |

| Muzzle velocity |

Variable |

| Effective firing range |

Variable (50–100 yards) |

| Feed system |

Muzzle-loaded |

“Brown Bess” is a nickname of uncertain origin for the British Army‘s muzzle-loading smoothbore Land Pattern Musket and its derivatives. This musket was used in the era of the expansion of the British Empire and acquired symbolic importance at least as significant as its physical importance. It was in use for over a hundred years with many incremental changes in its design. These versions include the Long Land Pattern, the Short Land Pattern, the India Pattern, the New Land Pattern Musket and the Sea Service Musket.

The Long Land Pattern musket and its derivatives, all .75 caliberflintlock muskets, were the standard long guns of the British Empire‘s land forces from 1722 until 1838, when they were superseded by a percussion cap smoothbore musket. The British Ordnance System converted many flintlocks into the new percussion system known as the Pattern 1839 Musket. A fire in 1841 at the Tower of Londondestroyed many muskets before they could be converted. Still, the Brown Bess saw service until the middle of the nineteenth century.

Most male citizens of the American Colonies were required by law to own arms and ammunition for militia duty.[1] The Long Land Pattern was a common firearm in use by both sides in the American War of Independence.[2]

In 1808 during the age of Napoleon, the United Kingdom subsidised Sweden in various ways as the British anxiously wanted to keep an ally in the Baltic Sea area, among other things deliverances of war material and with those, significant numbers of Brown Bess muskets for use in the Finnish War.[3]

During the Musket Wars (1820s–30s), Māori warriors used Brown Besses, having purchased them from European traders at the time. Some muskets were sold to the Mexican Army, which used them during the Texas Revolution of 1836 and the Mexican-American Warof 1846 to 1848. Brown Besses saw service in the First Opium Warand during the Indian rebellion of 1857. Zulu warriors, who had also purchased them from European traders, used them during the Anglo-Zulu War in 1879. One was even used in the Battle of Shiloh in 1862.[4]

Origins of the name[edit]

One hypothesis is that the “Brown Bess” was named after Elizabeth I of England, but this lacks support. It is not believed that this name was used contemporaneously with the early Long Pattern Land musket but that the name arose in late years of the 18th century when the Short Pattern and India Pattern were in wide use.

Early uses of the term include the newspaper, the Connecticut Courant in April 1771, which said “… but if you are afraid of the sea, take Brown Bess on your shoulder and march.” This familiar use indicates widespread use of the term by that time. The 1785 Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue, a contemporary work that defined vernacular and slang terms, contained this entry: “Brown Bess: A soldier’s firelock. To hug Brown Bess; to carry a fire-lock, or serve as a private soldier.” Military and government records of the time do not use this poetical name but refer to firelocks, flintlock, muskets or by the weapon’s model designations.

However, the origin of the name may be much simpler, if vulgar.

In the days of lace-ruffles, perukes, and brocade

Brown Bess was a partner whom none could despise –

An out-spoken, flinty-lipped, brazen-faced jade,

With a habit of looking men straight in the eyes –

At Blenheim and Ramillies, fops would confess

They were pierced to the heart by the charms of Brown Bess.

Kipling’s poem most possibly “hits the mark” although he may have based his poem on an earlier but similar “Brown Bess” poem published “Flights of Fancy (No. 16) in 1792. Of course, the name could have been initially inspired by the older term of the “Brown Bill” and perhaps the barrels were originally varnished brown, but it is well known in literary circles that the name “Brown Bess” during the period in question in the 17th to early 19th centuries is not a reference to a color or a weapon but to simply refer to a wanton prostitute [or harlot].[5] Such a nickname would have been a delight to the soldiers of the era who were from the lower classes of English and then British society. So far, the earliest use noted so far of the term “Brown Bess” was in a 1631 publication, John Done’s “POLYDORON: OR A Mescellania of Mo∣rall, Philosophicall, and Theologicall Sen∣tences.” at Page 152:

Things profferd and easie to come by, diminish them∣selves in reputation & price: for how full of pangs and dotage is a wayling lover, for it may bee some browne bes∣sie? But let a beautie fall a weeping, overpressed with the sicke passion; she favours in our thoughts, something Turnbull.

The Land Pattern Muskets

The Long Land Pattern “Brown Bess” musket was the British infantryman’s basic arm from about 1740 until the 1830s.

From the 17th century to the early years of the 18th century, most nations did not specify standards for military firearms. Firearms were individually procured by officers or regiments as late as 1745, and were often custom-made to the tastes of the purchaser. As the firearm gained ascendancy on the battlefield, this lack of standardisation led to increasing difficulties in the supply of ammunition and repair materials. To address these difficulties, armies began to adopt standardised “patterns”. A military service selected a “pattern musket” to be stored in a “pattern room”. There it served as a reference for arms makers, who could make comparisons and take measurements to ensure that their products matched the standard.

Stress-bearing parts of the Brown Bess, such as the barrel, lockwork, and sling-swivels, were customarily made of iron, while other furniture pieces such as the butt plate, trigger guard and ramrod pipe were found in both iron and brass. It weighed around 10 pounds (4.5 kg) and it could be fitted with a 17 inches (430 mm) triangular cross-section bayonet. The weapon did not have sights, though it could be aimed using the bayonet lug as a crude sight.

The earliest models had iron fittings, but these were replaced by brass in models built after 1736. Wooden ramrods were used with the first guns but were replaced by iron ones, although guns with wooden ramrods were still issued to troops on American service until 1765 and later to loyalist units in the American Revolution. Wooden ramrods were also used in the Dragoon version produced from 1744–71 for Navy and Marine use.

The accuracy of the Brown Bess was fair, as with most other muskets. The effective range is often quoted as 175 yards (160 m), but the Brown Bess was often fired en masse at 50 yards (46 m) to inflict the greatest damage upon the enemy. Military tactics of the period stressed mass volleys and massed bayonet charges, instead of individual marksmanship. The large soft projectile could inflict a great deal of damage when it hit and the great length of the weapon allowed longer reach in bayonet engagements.

As with all similar smooth bore muskets, it is possible to improve the accuracy of the weapon by using musket balls that fit more tightly into the barrel. The black powder would quickly foul the barrel, making it more and more difficult to reload a tighter-fitting round after each shot and increasing the risk of the round jamming in the barrel during loading. Since tactics at the time favoured close range battles and speed over accuracy, smaller and more loosely fitting musket balls were much more commonly used. The Brown Bess had a barrel bore of .75 caliber, and the typical round used was around .69 caliber.

While the looser-fitting musket ball reduced the effective range of a single musketeer firing at a single man-sized target to around 50 yards (46 m) to 75 yards (69 m), the Brown Bess was rarely used in single combat. Since individual soldiers are not aimed for en masse volleys, the effective range of the Brown Bess when fired en masse was easily 100 yards (91 m) or more.

Standard European targets included strips of cloth 50 yards long to represent an opposing line of infantry, with the target height being six feet for infantry and eight feet, three inches for cavalry. Estimations of hit probability at 175 yards could be as high as 75 percent in volley fire. This, however, was without allowances for the gaps between the soldiers in an opposing line, for overly tall targets or the confusing and distracting realities of the battlefield. Modern testers shooting from rigid rests, using optimum loads and fast priming powder, report groups of circa five inches at fifty yards.[6]

Variations

To address these difficulties, armies began to adopt standardised “patterns”. A military service selected a “pattern musket” to be stored in a “pattern room”.

There it served as a reference for arms makers, who could make comparisons and take measurements to ensure that their products matched the standard.

Stress-bearing parts of the Brown Bess, such as the barrel, lockwork, and sling-swivels, were customarily made of iron, while other furniture pieces such as the butt plate, trigger guard and ramrod pipe were found in both iron and brass.

It weighed around 10 pounds (4.5 kg) and it could be fitted with a 17 inches (430 mm) triangular cross-section bayonet. The weapon did not have sights, though it could be aimed using the bayonet lug as a crude sight.

The earliest models had iron fittings, but these were replaced by brass in models built after 1736. Wooden ramrods were used with the first guns.

But were replaced by iron ones, although guns with wooden ramrods were still issued to troops on American service until 1765 and later to loyalist units in the American Revolution. Wooden ramrods were also used in the Dragoon version produced from 1744–71 for Navy and Marine use.

The accuracy of the Brown Bess was fair, as with most other muskets. The effective range is often quoted as 175 yards (160 m), but the Brown Bess was often fired en masse at 50 yards (46 m) to inflict the greatest damage upon the enemy.

Military tactics of the period stressed mass volleys and massed bayonet charges, instead of individual marksmanship.

The large soft projectile could inflict a great deal of damage when it hit and the great length of the weapon allowed longer reach in bayonet engagements.

As with all similar smooth bore muskets, it is possible to improve the accuracy of the weapon by using musket balls that fit more tightly into the barrel.

The black powder would quickly foul the barrel, making it more and more difficult to reload a tighter-fitting round after each shot and increasing the risk of the round jamming in the barrel during loading.

Since tactics at the time favoured close range battles and speed over accuracy, smaller and more loosely fitting musket balls were much more commonly used.

The Brown Bess had a barrel bore of .75 caliber, and the typical round used was around .69 caliber.

While the looser-fitting musket ball reduced the effective range of a single musketeer firing at a single man-sized target to around 50 yards (46 m) to 75 yards (69 m), the Brown Bess was rarely used in single combat.

Since individual soldiers are not aimed for en masse volleys, the effective range of the Brown Bess when fired en masse was easily 100 yards (91 m) or more.

Standard European targets included strips of cloth 50 yards long to represent an opposing line of infantry, with the target height being six feet for infantry and eight feet, three inches for cavalry. Estimations of hit probability at 175 yards could be as high as 75 percent in volley fire.

This, however, was without allowances for the gaps between the soldiers in an opposing line, for overly tall targets or the confusing and distracting realities of the battlefield.

Modern testers shooting from rigid rests, using optimum loads and fast priming powder, report groups of circa five inches at fifty yards.[6]

Variations

X-ray of a Brown Bess musket recovered by LAMP archaeologists from an American Revolutionary War era shipwreck lost in December 1782.

It is believed to be a 1769 Short Land Pattern, and is loaded with

buck and ball.

Many variations and modifications of the standard pattern musket were created over its long history. The earliest version was the Long Land Pattern of 1722, a 62-inch (160 cm) long (without bayonet) and with a 46-inch (120 cm) barrel.

It was later found that shortening the barrel did not detract from accuracy but made handling easier, giving rise to the Militia (or Marine) Pattern of 1756 and the Short Land Pattern of 1768, which both had a 42-inch (110 cm) barrel.

Another version with a 39-inch (99 cm) barrel was first manufactured for the British East India Company, and was eventually adopted by the British Army in 1790 as the India Pattern.

Towards the end of the life of the weapon, there was a change in the system of ignition. The flintlock mechanism, which was prone to misfiring, especially in wet weather, was replaced by the more reliable percussion cap.

The last flintlock pattern manufactured was selected for conversion to the new system as the Pattern 1839. A fire at the Tower of London destroyed large stocks of these in 1841, so a new Pattern 1842 musket was manufactured.

These remained in service until the outbreak of the Crimean War when they were replaced by the Minie and the P53 Enfield rifled musket.

| Pattern |

Picture |

In service |

Barrel Length |

Overall Length |

Weight |

| Long Land Pattern |

|

1722–93

standard Infantry Musket 1722–68

(supplemented by Short Land Pattern from 1768) |

46-inch (120 cm) |

62.5-inch (159 cm) |

10.4 pounds (4.7 kg) |

| Short Land Pattern |

|

1740–97

1740 (Dragoons)

1768 (Infantry)

standard Infantry Musket 1793–97 |

42-inch (110 cm) |

58.5-inch (149 cm) |

10.5 pounds (4.8 kg) |

| India Pattern |

|

1797–1854

standard Infantry Musket 1797–1854

(Some in use pre-1797 purchased from the East India Company for use in Egypt) |

39-inch (99 cm) |

55.25-inch (140.3 cm) |

9.68 pounds (4.39 kg) |

| New Land Pattern |

|

1802–54

Issued only to the Foot Guards and 4th Regiment of Foot |

39-inch (99 cm) |

55.5-inch (141 cm) |

10.06 pounds (4.56 kg) |

| New Light Infantry Land Pattern |

The detail differences between this musket and the standard New Land Pattern were a scrolled trigger guard similar to that of the Baker Rifleexcept more rounded, a browned barrel and a notch back-sight, the bayonet lug being used as the fore-sight. |

1811–54

Issued only to the 43rd, 51st, 52nd, 68th, 71st and 85th Light Infantry and the Battalions of the 60th Foot not armed with rifles |

39-inch (99 cm) |

55.5-inch (141 cm) |

10.06 pounds (4.56 kg) |

| Cavalry Carbine |

|

1796–1838

Issued to cavalry units |

26-inch (66 cm) |

42.5-inch (108 cm) |

7.37 pounds (3.34 kg) |

| Sea Service Pattern |

|

1778–1854

Issued to Royal Navy ships, drawn by men as required, Marines used Sea Service weapons when deployed as part of a ship’s company but were issued India Pattern weapons when serving ashore |

37-inch |