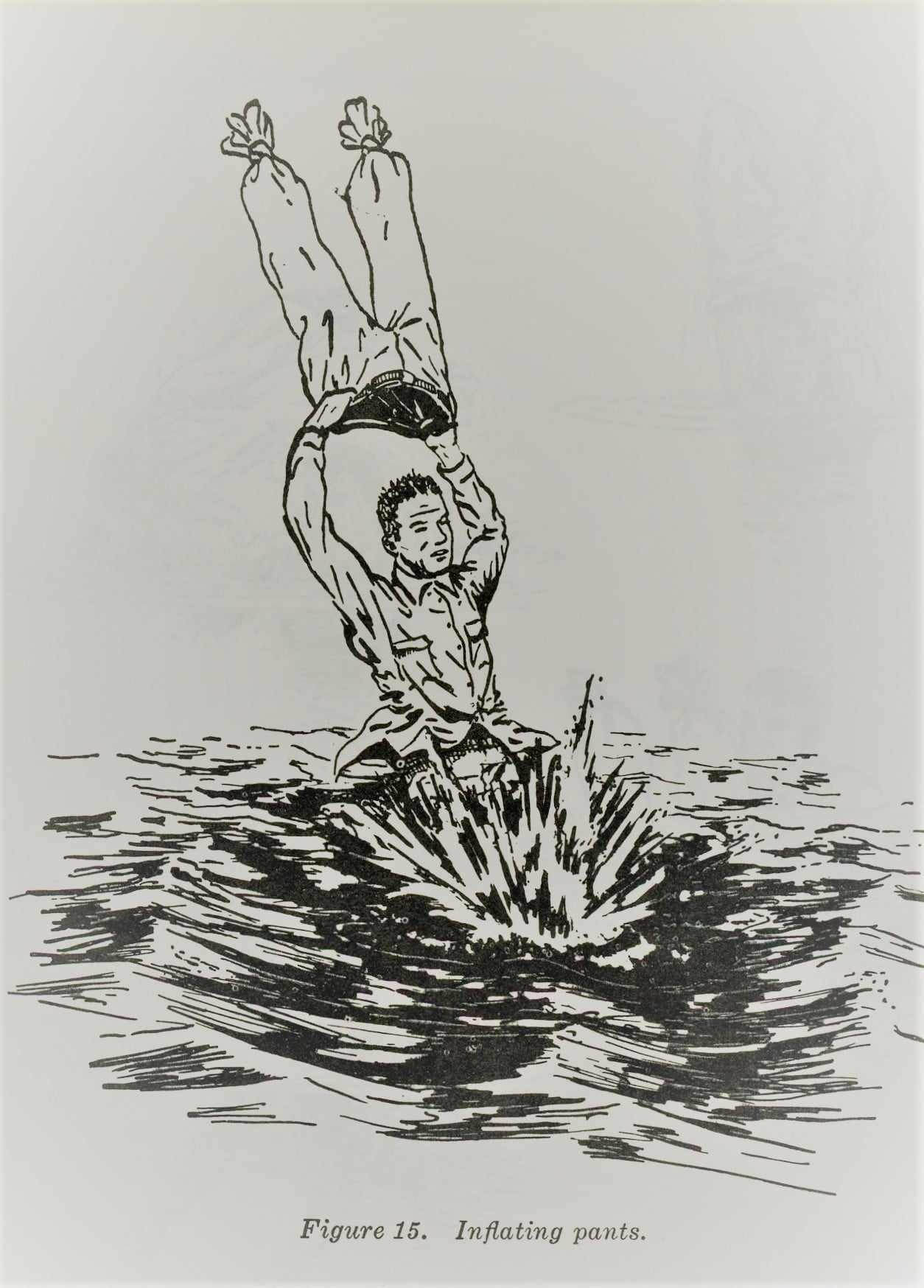

The author’s favorite Kit Guns are the stainless-steel, 4-inch-barreled S&W Model 63 (top) and the blued, alloy-frame, 3.5-inch-barreled S&W Model 43 (bottom). One of these guns rides on his hip every day as he rides the ranch doing chores in the off-season.

|

For the last month or so I’ve been running axis deer hunts on our Hill Country lease. The days are long, so there are lots of chores to do between the morning and evening hunts. One of my favorites is running my raccoon traps. Few of my clients have ever trapped before, so they often ask to ride along as I check my trapline and dispatch as many of the protein-feeder-raiding thieves as possible. I am astounded at how many of those clients ask about the classic Smith & Wesson Kit Gun that generally resides on my hip.

The Kit Gun made its debut in the mid-1930s as the .22/32 Kit Gun. It was marketed to the outdoorsmen of the day who often carried their necessities in kit bags. The revolvers often rode in the bags for which they were named, but just as many rode on the hips of hikers and ranchers and in the tackle boxes of fishermen.

The Kit Gun was light, compact, accurate, and capable of dealing with the various nuisances outdoorsmen most commonly encountered. Not surprisingly, it was wildly successful.

The first Kit Guns were built on the old S&W I-Frame until about 1960, when S&W began building the guns on the slightly larger J-Frame.

In addition to the standard .22 LR Kit Gun, Airweight and .22 Magnum variants were also available. When Smith & Wesson began numbering all its guns, the blued Kit Gun became the Model 34, the stainless variant was the Model 63, the Airweight became the Model 43, and the Magnum version was called the Model 51.

All came standard with adjustable sights, wood grips, and the old-world craftsmanship for which those old S&W revolvers were known.

I rarely wear a .22 during deer season, but one of my .22 LR Kit Guns gets the nod in the off-season when snakes and coons are the varmints I’m most likely to encounter. My favorite Kit Gun variants are the Models 43 and 63.

The Model 43 has an alloy frame and a round butt. Its barrel is an odd but handy 3.5 inches long with a relatively trim taper. It has the standard S&W adjustable rear sight with a black serrated front. All the examples I’ve seen have a rich, lustrous blue finish that’s darn hard to find these days, and all are beautifully built. As far as carry guns go, the trim, featherweight beauty is tough to beat.

The Model 63 is a stainless-steel gun. Mine has a 4-inch barrel, though 2- and 6-inch barrels were also available. The 63’s barrel is relatively trim, as are its stocks. S&W’s classic adjustable rear sight and a ramp front sight with an orange insert are standard. The combination carries easily and shoots great out to as far as most folks are likely to shoot a rimfire revolver.

The author carries this S&W Airweight Model 43 Kit Gun a great deal, and it’s so lightweight, he often forgets he has it on.

|

I go back and forth between the two Kit Gun variants. The stainless gun holds up better to the day-in, day-out wear and tear a ranch gun must endure, and I wear it quite often in a pancake-style holster from Tucker Gun Leather (www.tuckergunleather.com). But as much as I like my 63, the 43’s alloy frame and trim tube make it such a joy to carry that I find myself wearing it more often than not.

Worn high on my hip in a belt scabbard from Andy Langlois (www.andysleather.com), the diminutive sixgun is hardly noticeable, but when it’s time to dispatch a trapped raccoon, fox, or bobcat, my Airweight Kit Gun is instantly at hand.

The Kit Gun is not just a short-range plinker, though. I use mine to dispatch wounded big game without excessive damage to the meat, hide, or head. [Editor’s note: In some states it is illegal to even finish wounded big game with a .22. Be aware of local laws.]

In fact, I finished an axis deer and a Corsican sheep with mine just last week. Both were shot well, but I don’t like them to suffer, and the clients don’t seem to mind when I hasten their demise with my little .22. Federal’s 40-grain solid drives deep enough to get the job done without damaging the meat or the hide.

I use them on hogs, too. When a big boar hog runs afoul of a snare, my Kit Guns are accurate enough to put some 40-grain sedatives into their vitals from a distance. I don’t mind getting closer, but a big hog can do a tremendous amount of damage if you get it worked up.

I’ve found that it’s better to shoot them before they see me. Those 40-grain solids drive deep enough to get the job done surprisingly fast when I place my shots accurately.

When I’m not using my Kit Gun to dispatch varmints, it gets a heck of a workout on dirt clumps and cow patties.

Serious plinking is, in my opinion, the very best way to sharpen your shooting and keep it that way, so I do lots of it. I may not hit every egg-sized object I take aim at from long range, but I hit enough, and I don’t miss the lucky ones by much.

When you’re good enough to hit even a cantaloupe-sized object at 100 yards, you’re well on your way to becoming a serious pistolero. The sight alignment and trigger control those long-range sessions build will improve every other aspect of your shooting, too.

Though the classic Kit Guns have come and gone, S&W has introduced several new variants over the years, including .32, .38 Special, and .44 Special guns. Perhaps my favorite recent Kit Gun is the little 2-inch-barreled, flyweight Model 317 that came out in the 1990s.

I sold mine long ago to buy something stupid (like food or gas), but that tiny gun spent a lot of time hanging on a lanyard around my neck as I paddled my canoe up and down water moccasin-infested Oyster Creek near my home.

Today’s Smith & Wesson line is rich with Kit Guns. The same 1.875-inch barreled, 10.8-ounce Model 317 I used to carry is back in the line, as is a 3-inch, fiber-optic-sighted 317. A Model 63 with a 3-inch barrel and fiber-optic sights and a hammerless, DAO Model 43 C round out the .22 LR Kit Gun line. All have eight-shot cylinders.

For anyone who needs a little more horsepower, the Kit Gun line also includes a pair of seven-shot .22 Magnums. The 10.8-ounce Model 351 PD has fiber-optic sights, a 1.875-inch barrel, a blued finish, and Rosewood grips.

The other offering is the hammerless, snub nosed Model 351 C. Both are perhaps better suited to self-defense than trail use, but they would be handy on the trapline.

It’s easy to get wrapped up in selecting the ultimate big-bore hunting revolver or finding the perfect carry gun, but the truth is few folks shoot those big boomers much.

A good rimfire, on the other hand, will get shot a lot. Smith & Wesson’s fine Kit Gun in any of it numerous variations is a great choice. You’ll shoot it lots because .22 ammo is cheap, and you’ll become a better shooter in the process.