Category: War

M60: Cold War Guardian

The M42 — known as the “Duster” — was a light armored air defense system that arguably became better known for its capabilities against the communist ground forces in the Vietnam War. Originally built for the U.S. Army between 1952 and 1960, a total of 3,700 M42s were built. The weapon system first saw use in the Korean War and served through the 1980s.

The M42 Duster was a spinoff of the M41 series light tank, the Walker Bulldog, which replaced the M24 Chaffee light tank. A 500 horsepower, air-cooled, Continental six-cylinder gas engine powered the M42 to a max speed of 45 mph and a range of 100 miles.

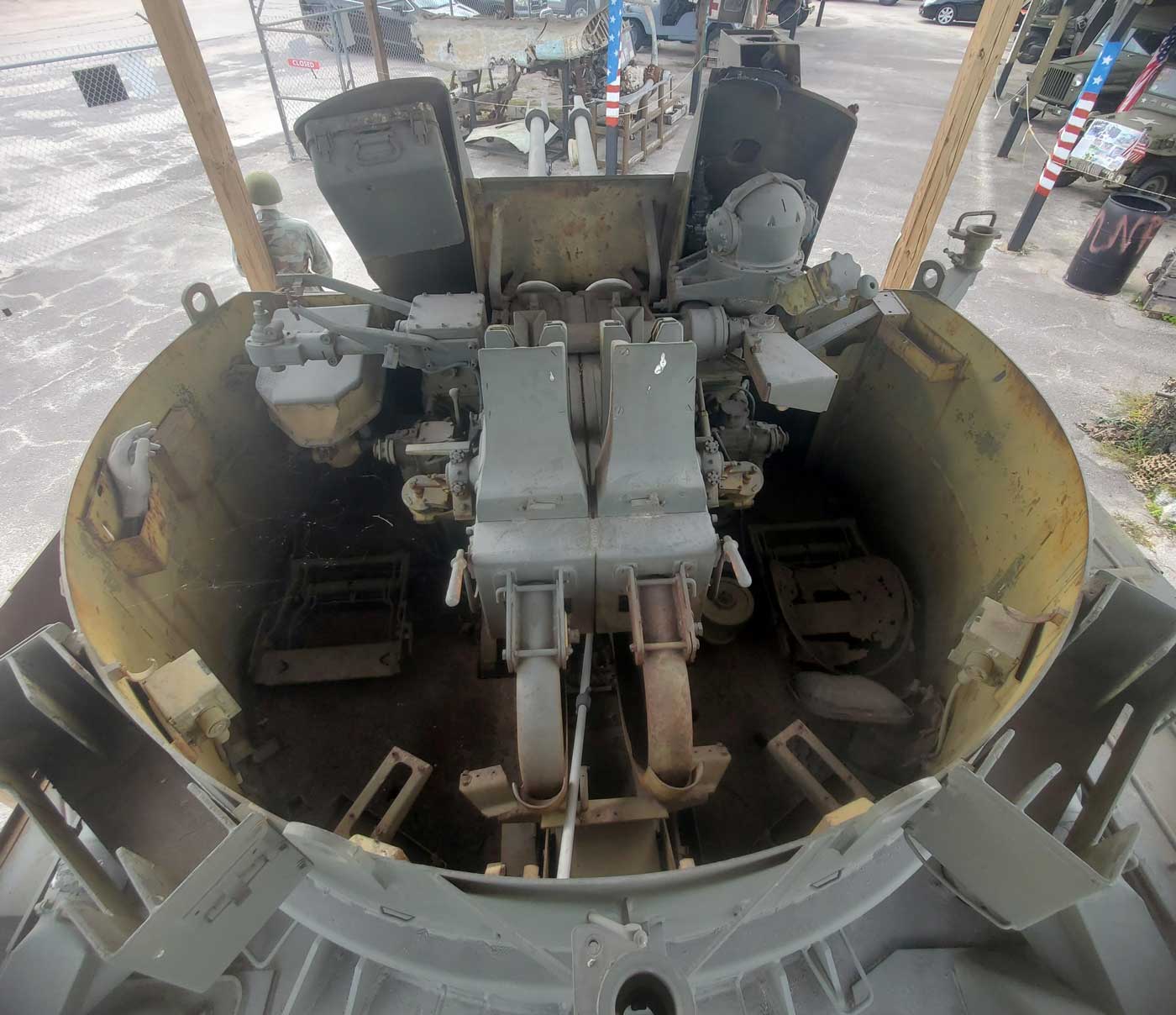

The Duster’s hull was divided into three sections:

- the forward section was for the driver and commander/radio operator,

- the center section was the base for the dual Bofors 40mm L/60 guns and ammunition, and

- the rear section held the engine, fuel and generator.

Designed for a six-man crew consisting of a driver, commander, gunner, sight setter and two ammo loaders, the Duster was usually manned by only four men. There was also an externally mounted .30 caliber M1919 Browning machine gun for vehicle defense.

Twin Bofors 40mm L/60 Guns

The twin 40mm Bofors guns had a combined rate of fire of 240 rounds per minute, and each fed from a four-round clip with either armor piercing or high explosive warhead. With an ammo capacity of 336 rounds, the Duster had about 85 seconds of fire, with a maximum ground-to-ground range of 9,475 meters. The flash suppressors were changed from the standard conical design to a three-prong model for use with the Duster.

The turret of the M42 was designed to fit the M41 hull without modification and was capable of 360-degree rotation, either mechanically or hydraulically. The Bofors guns could be adjusted from -3 degrees to +85 degrees and could also be powered mechanically or hydraulically.

In Effect

The Duster fire control system was controlled by the commander, who located the target. He would estimate the speed, direction, and angle, entering it into the sighting system. Then, the driver would position the turret and elevate the guns to center the target into the reflex sight, which computed the lead distance and tracked the target. Once a steady lock was on, the firing system was engaged, and the guns would fire until the target was destroyed or the commander ordered a cease-fire.

The Duster could also perform fire missions using data from artillery fire data centers and be on target faster than the artillery pieces. The Duster was also a great asset for nighttime missions using the infrared mode on the searchlight. With this search mode, the Dusters could search for the enemy without giving away their position. Once a target was found, the searchlight was switched over to light mode, and the target was engaged.

The Bofors is an anti-aircraft gun designed in the mid-30s to fill the gap between small-caliber rapid-fire machine guns and large slow-firing cannons. The Bofors entered service in 1932, and by 1939, it was in service with 18 countries.

During WWII, the 40mm Bofors was used by a majority of military units. It was used heavily aboard U.S. Navy ships, such as the Iowa-class battleships, for anti-aircraft duties as a dual- or quad-mount alongside the 20mm Oerlikon.

The Bofors also found a home in the air aboard the AC-130 Spectre gunship. Since its inception, twin Bofors guns have been mounted on the Spectre, beginning in the early seventies until its final retirement in 2020.

A New Leave

In the early 1960s, the U.S. Army began transferring the M42 to National Guard units as the system was deemed unsatisfactory for air defense in the jet age with its old-fashioned pom-pom guns. In place of the aging Duster, the Army began deploying HAWK surface-to-air missile batteries.

Around 1966, the Army began recalling the M42 Duster from National Guard units for service in Vietnam. It was here that the Duster made a name for itself, making a notable impact during the war. Upon arriving in Vietnam, the Dusters were commonly deployed in pairs in a ground support role. The enemy feared the Duster, with the Viet Cong calling them “Fire Dragons.”

While the Duster excelled in many areas, it had its limitations. The gasoline-powered engine was prone to catching on fire when overheated, and the terrain of Vietnam was hard on the transmission and suspension. The ammunition for the Bofors gun had a highly sensitive fuse, which caused issues with premature detonation when fired through the dense jungle foliage.

The Duster was deployed as a convoy escort, perimeter defense, and infantry support. Also, it took to the water, being mounted on an M8 landing craft for riverine fire support with the 9th Infantry Mobile Riverine Force.

In 1968, Dusters from the U.S. Army 1st battalion attached to the 3rd Marine Division engaged the enemy during the 77-day siege at the Battle of Khe Sanh. Dusters expended more than 20,000 40mm shells.

Duster Battalions

The Army deployed three Duster battalions to the Republic of Vietnam, with crews trained at Fort Bliss, Texas. Each Battalion consisted of a headquarters battalion and four line batteries with two platoons, each with eight Dusters.

The first battalion arrived in South Vietnam during the second half of 1966 and supported U.S. Marine units in Khe Sanh and Army divisions in the I Corps region. The second battalion arrived later in 1966 and was deployed around Bien Hoa Airbase along with vehicle-mounted M45 Quadmount .50-cal. guns and searchlight jeeps. The 3rd battalion arrived in mid-1967, deployed to the central highlands at An Khe, and supported regional fire bases.

When the battalions were fully deployed, there were over 200 Dusters in-country.

Depending on which legend you believe, the Duster moniker came from either the cloud of dust while blazing down the dirt trails of Vietnam, or because of its 50-meter bursting-radius 40mm rounds that turned the enemy to dust.

Going Home

By 1971, the Army began moving Duster units out of Vietnam after firing more than 4 million rounds and recording over 200 kills in support of infantry units. Overall, the Duster was a devastating tool that excelled at convoy escorts and base perimeter defense.

Most Dusters were turned over to units in the Army of the Republic of Vietnam, while the remaining units at Fort Bliss were returned to the National Guard until the last unit retired in 1988, marking the end of an era.

Naked Commandos: Burma, 1945

“The bulwark of this Volkssturm in Japan proper is the Second National Army, which in peacetime consists of a large group of untrained males of military age. With the small amount of training now being given this group and with the formal registering on its rolls of all 17- and-18-year-olds since November 1944, the use of civilians in the defense of the Japanese homeland begins to assume increasing military importance.”

—Secret U.S. Military Intelligence document from the Pacific Theater of Operations, March 1945

While the Allied concept of “unconditional surrender” of Axis forces in Europe was sound, the prospects of a national Japanese surrender seemed unlikely. Before anyone knew anything about the war-ending potential of the atomic bomb, American military planners had to prepare to overcome a fanatical defense of the Japanese home islands—a battle during which the Japanese military appeared ready to sacrifice their entire population to protect their homeland.

But while the Japanese spirit was willing, their physical resources were growing weak. The emperor’s forces struggled to provide enough firearms and ammunition to their combat troops. To train and supply a large civilian militia with effective modern small arms would require extreme ingenuity to match the traditional Japanese willingness to sacrifice. Consequently, the Japanese would develop some of the crudest firearms of World War II.

Setting The Stage For Operation Downfall

Allied leaders concluded that they could not wait for a blockade and intensive bombings to bring about a Japanese surrender—a massive invasion of the home islands was necessary. Meanwhile, a timeline was set for the defeat of Japan within one year of the surrender of Germany. The larger plan, dubbed “Operation Downfall,” was divided into two parts: Operation Olympic and Operation Coronet.

Olympic was to be the invasion of Kyūshū, scheduled for Nov. 1, 1945. Coronet was the second phase, with a massive force planned to invade Honshu in March 1946. All the main preparations were made without any knowledge of atomic bombs, and until the successful A-bomb test (July 16, 1945), it would have been folly to plan for the intervention of any secret weapon. A massive amount of brute force was the Allied recipe for success.

As American forces progressed in the island-hopping campaign, reaching islands closer to Japan proper, they encountered more Japanese civilians in the combat zone. These encounters provided a clearer picture of what Allied forces could expect when they invaded the Japanese home islands. American intelligence began to understand the scope of the Japanese militia, and the militarists plans for “The Glorious Death of One Hundred Million.”

In a March 28, 1945, Military Research bulletin, American intel resources reported on the “employment of Japanese civilians in local defense:”

“It has long been the policy of the Japanese Army, even in peacetime, to keep close check upon all Japanese males of military age, not only as to whereabouts and amount of military training received but also as to education and occupational skills. This policy has been facilitated by assigning every fit male to a reserve component of the Army at the time of his conscription examination. In peacetime, those picked for conscript training, released after two years of active service, became members of the First Reserve. Those picked for a short term of replacement training formed the Conscript Reserve.

Both trained groups automatically entered the First National Army on reaching the age of 37. All other males 17-40 (now 17-44) who were not declared “unfit” became members of the Second National Army, a large body of untrained militia subject to call in emergency.

Japan has declared her intention to employ this reservoir of civilian manpower in local defense of the homeland and overseas areas, While It is true that Japanese civilians have not been used too effectively in the areas already attacked (see Bulletin 10), the following factors indicate that the employment of this Japanese “people’s army” will become more important as the war nears Japan Proper:

-

- Greater numbers of Japanese nationals will be encountered

- The Army has had greater experience in handling civilians

- The individual’s determination to fight will increase as the threat to the homeland becomes more imminent

The available numbers, the past employment, and preparations made by the Japanese for the use of these civilian fighters, and the general methods of employment are discussed below.

It must be remembered that the Japanese Army will also continue to use natives as far as possible for military labor and as auxiliary forces, but this study is concerned only with the less variable use of Japanese nationals residing in operational areas.”

The report concluded that 17,450,000 men aged 15-59 were available as militia troops in the Japanese home islands.

“The proportion of the above numbers actually available as effective fighting men will be limited by several factors, including local administrative problems and the ability of the Japanese to arm and equip the personnel present in areas under attack.”

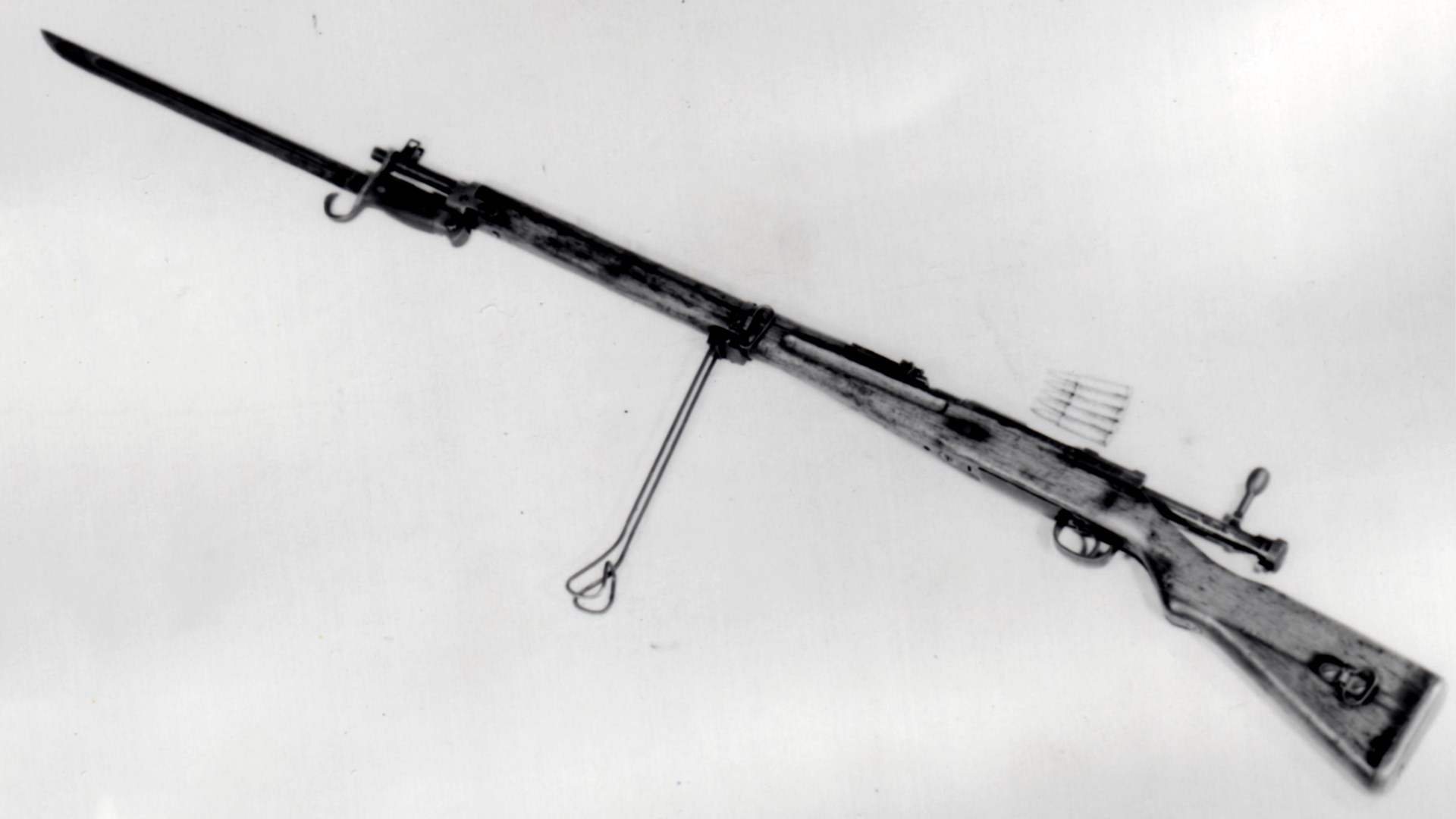

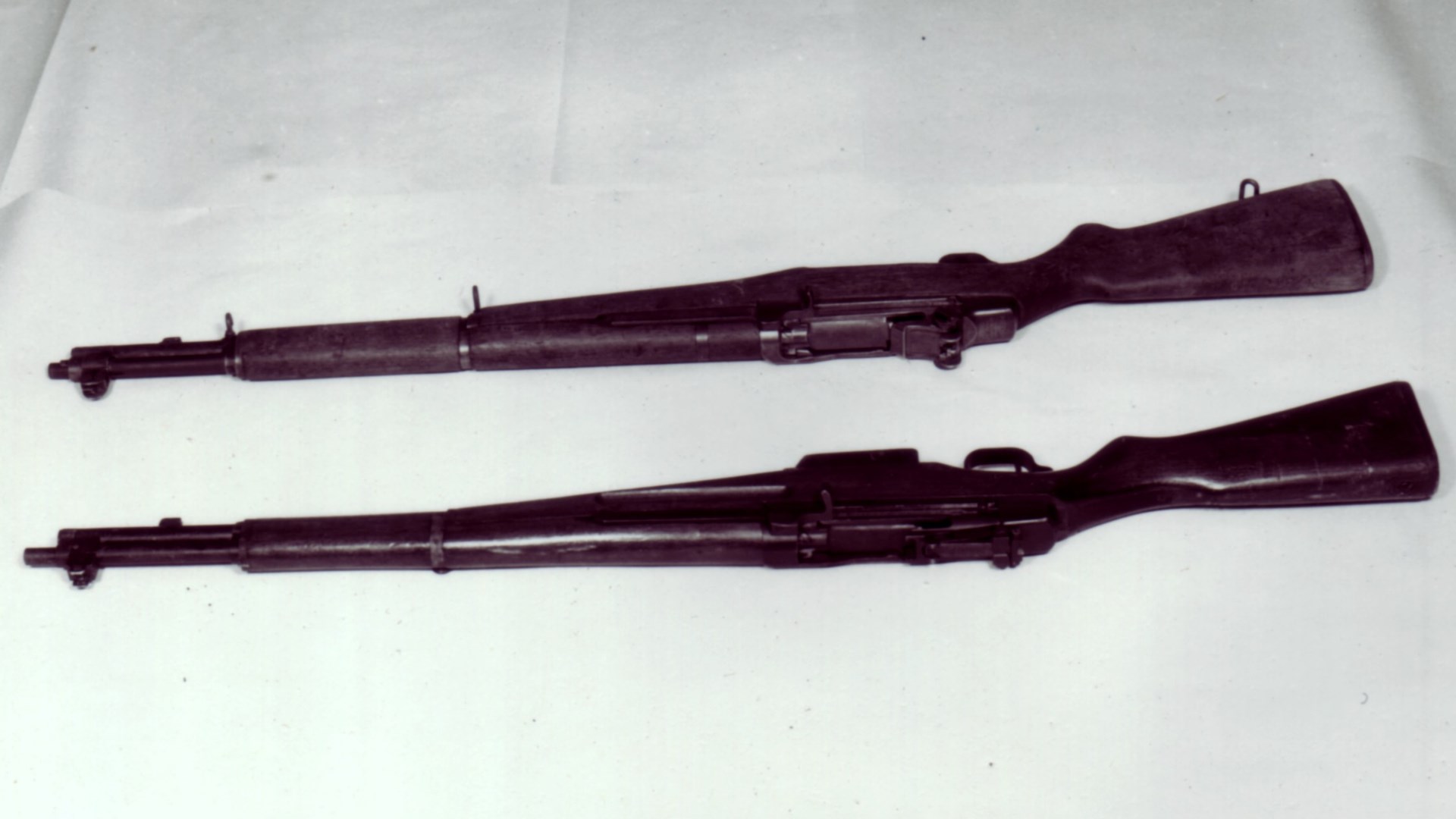

U.S. troops in the field captured various new and modified Japanese wfirearms. Of particular interest were the modifications to the Japanese Model 99 (1939) Pattern 7.7 mm Rifle. These were detailed in an Ordnance intelligence report, produced in late 1944:

“A Japanese 7.7mm rifle of the Model 99 (1939) pattern, recovered in the Ormoc area, is of extreme interest as it Indicates a possible relaxation in the standard of manufacture. The points of variance between this and other rifles of the same model previously recovered are as follows:

-

- The wire monopod has been omitted.

- The anti-aircraft lead arms on the back sight have been removed. Also, instead of the sight being machined in one piece, the sight base is now welded to the mount.

- The bolt knob is smaller and cylindrical in shape, instead of the usual oval ball.

- The safety knob is no longer knurled on its rear face, but is left square, just as it was when it was cut off the lathe.

- The wooden stock is much inferior in quality to that usually fitted.

According to a recently captured document, Japanese ordnance chiefs have expressed grave concern at the lack of essential ordnance supplies. With a view to remedying this condition, it was decided that the manufacture of certain items was to cease, while others were to be modified so that an intensified effort could be made to speed up production.”

The Type 99 7.7 mm Substitute Rifle

In 1943, the Japanese decided to simplify the standard Type 99 rifle and make a “substitute standard” small arm. These modifications included eliminating the sling, cleaning bar and bolt cover, while substituting inferior steel for parts like the bolt and barrel. The simplification eliminated the chromium plate in the barrel, used an inferior grade of wood for the stock, and revised the sight to a range of only 300 meters. This was called a Substitute Type 99 Rifle.

Japanese rifle collectors have uncovered a tremendous amount of information about the nuances of late-war Japanese arms production. Type 99 rifle collectors have described wide variations in the “Substitute Rifle,” including no serial or series number, unnumbered parts, mismatched parts, front sights missing guards, rear sights missing wings, alternate shapes to the bolt handle and varying types of butt plates.

During April 1945, Japan made a significant change in its civil defense forces, designating them as civilian militia, and by June, conscription laws had been enacted even while the militia was renamed the Volunteer Fighting Corps (Kokumin Giyū Sentōtai). By the end of June, more than 25 million Japanese men were deemed “combat capable” by their hopeful government, but very few of them could be equipped with firearms of any kind. The Volunteer Fighting Corps did not see action during the war, but an early precursor, the local home guard on Okinawa, was equipped with obsolete rifles, most notably the Type 22 Murata rifles (11 mm). In the home islands, all that was available in the short term were spears, swords, axes, clubs and crossbows. Hand grenades were the most plentiful of modern weapons.

The Japanese “Simple Rifle:” Crude Weapons For The Massed Militia

Preparing for the invasion they knew would come, the Japanese embarked on a quick program of simple weapons development to equip their mostly untrained militia. The resulting firearms are some of the rarest guns of the entire war. The following descriptions (and photos) come from a series of U.S. Ordnance Technical Intelligence reports compiled during the first few months of 1946.

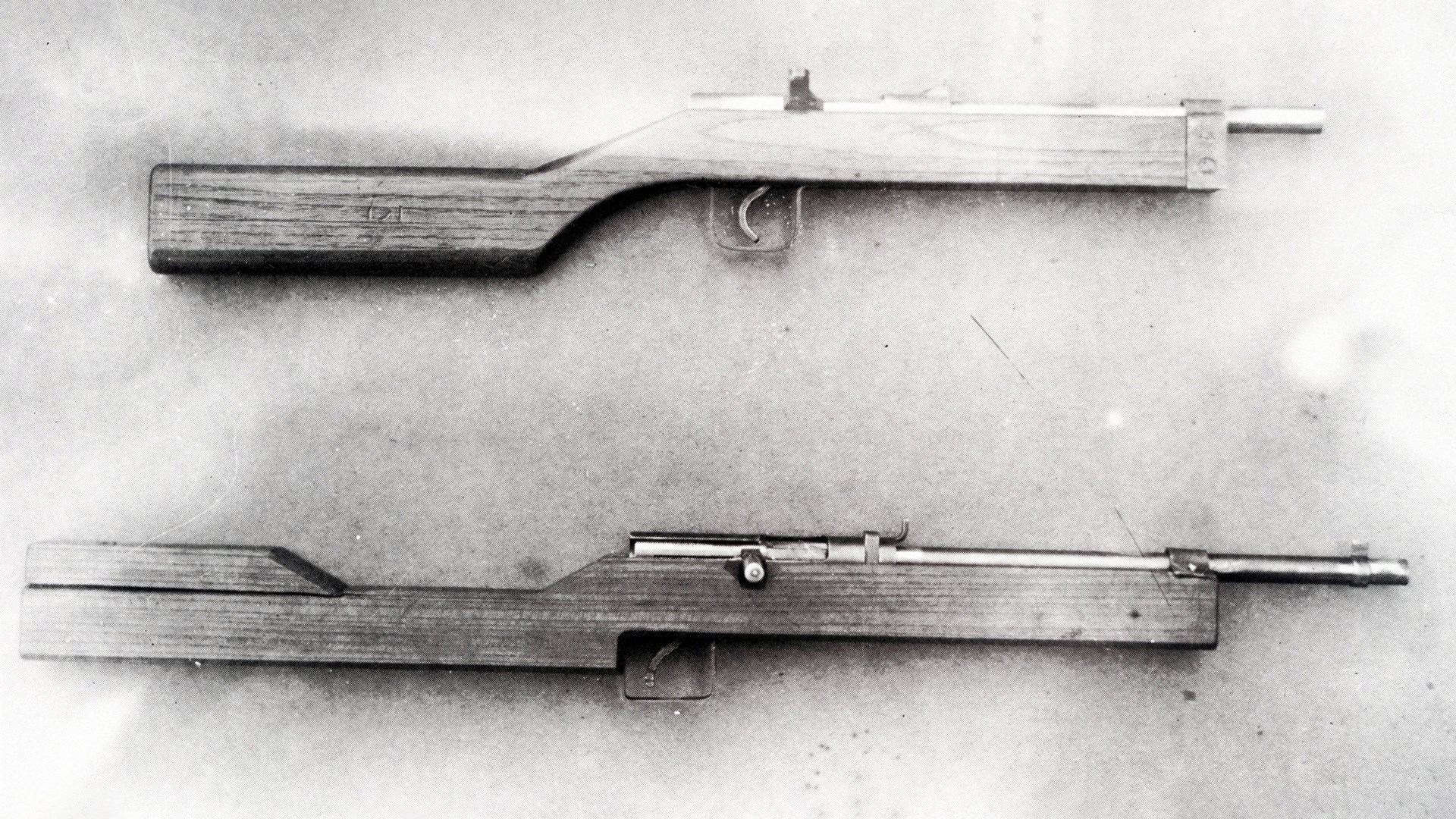

Simple 7.7 mm & 8 mm Rifles

A very simple rifle that would fire the standard 7.7 mm ammunition was attempted. The length of the barrel was 50 cm, and it was so simple in construction that it, as well as the other parts, could be made on an ordinary lathe. It was a bolt-action, single-shot piece that was intended to equip front-line defense troops in an invasion. However, as the ammunition proved too powerful, it was decided to make the rifle shorter and to use standard 8 mm 14th Year Type pistol ammunition, which proved much more satisfactory.

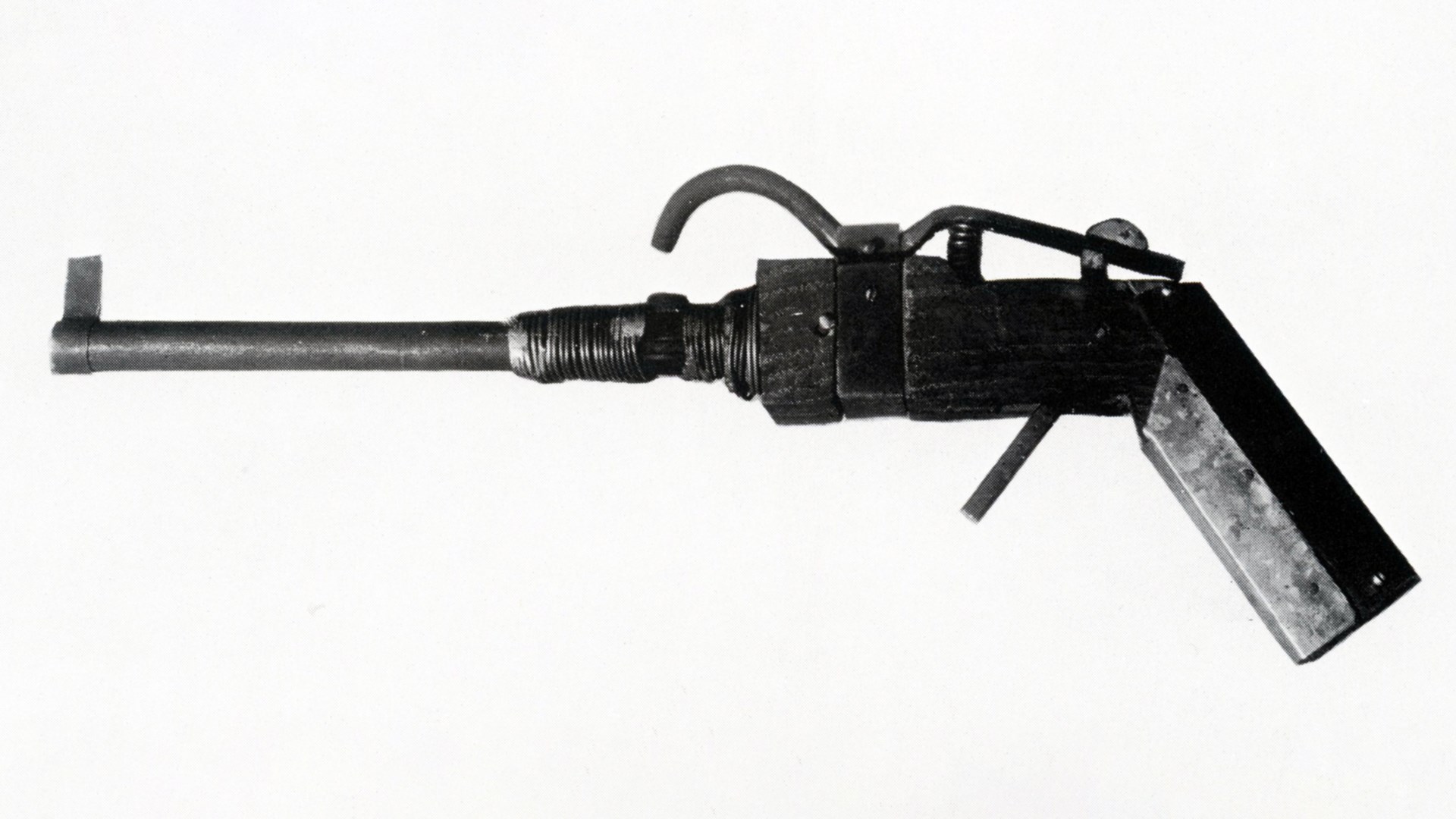

National Rifle & Pistol For Civilian Defense

This rifle was developed for the purpose of equipping volunteer defense troops and was a type that could be made by any small factory or smithy shop. The construction was simple as an ordinary piece of pipe (13 mm diameter) formed the barrel. It was loaded with 3 to 5 grams of blackpowder, and the projectile was made from ordinary bar stock cut in sections about 15 mm in length. It was fired by the hammer striking a primer-igniter cap that was placed over a small flash hole on top of the barrel. A pistol version of this firearm was also produced.

Type 5 Semi-Automatic Rifle (Garand copy)

The need for a semi-automatic rifle for the Japanese army was recognized in 1922, but the development of such a firearm was not begun until 1931 when several models were made; all proved unsatisfactory. This study lasted until 1937, at which time research was temporarily discontinued.

In March 1941, the inquiry was again started because of the progress on semi-automatic rifles in foreign countries. At this time, the 1st Section and the Kokura Army Arsenal designed several types of recoil and gas-operated rifles. The results of tests showed that none of the models were entirely satisfactory in operation, and because of the unforeseen difficulty in manufacturing such a rifle, research was again stopped.

About March 1944, there was a strong demand to develop a semi-automatic rifle, especially from the paratroop command. At that time, the Navy introduced a semi-automatic rifle copied from the U.S. M1 (Garand) Rifle that used the standard Japanese 7.7 mm ammunition. In April 1945, models were finished and tested. Although the test results were not entirely satisfactory due to breakage of parts, loading and feeding difficulties, they were considered good enough to adopt the gun. The rifle was standardized as the Type 5.

World War II finally ended after the atomic bomb attacks on Hiroshima (August 6) and Nagasaki (August 9). While the casualties from the two nuclear blasts were horrific, they pale in comparison to projected number of deaths if dozens of Allied infantry divisions assaulted Japan and Japanese militarist plans to sacrifice the entirety of their population to stop them came to fruition. Armed with bamboo spears and an odd assortment of crude firearms, the Japanese Volunteer Fighting Corps would have inflicted their share of casualties on the invaders, but the utter and tragic destruction of Japan and its people would certainly have followed.