One of the better pictures of what an Infantry Assault looks like.

The Battle of Germantown was a major engagement in the Philadelphia campaign of the American Revolutionary War. It was fought on October 4, 1777, at Germantown, Pennsylvania, between the British Army led by Sir William Howe, and the American Continental Army, with the 2nd Canadian Regiment, under George Washington.

After defeating the Continental Army at the Battle of Brandywine on September 11, and the Battle of Paoli on September 20.

Howe outmanoeuvred Washington, seizing Philadelphia, the capital of the United States, on September 26. Howe left a garrison of some 3,000 troops in Philadelphia, while moving the bulk of his force to Germantown, then an outlying community to the city.

Learning of the division, Washington determined to engage the British.

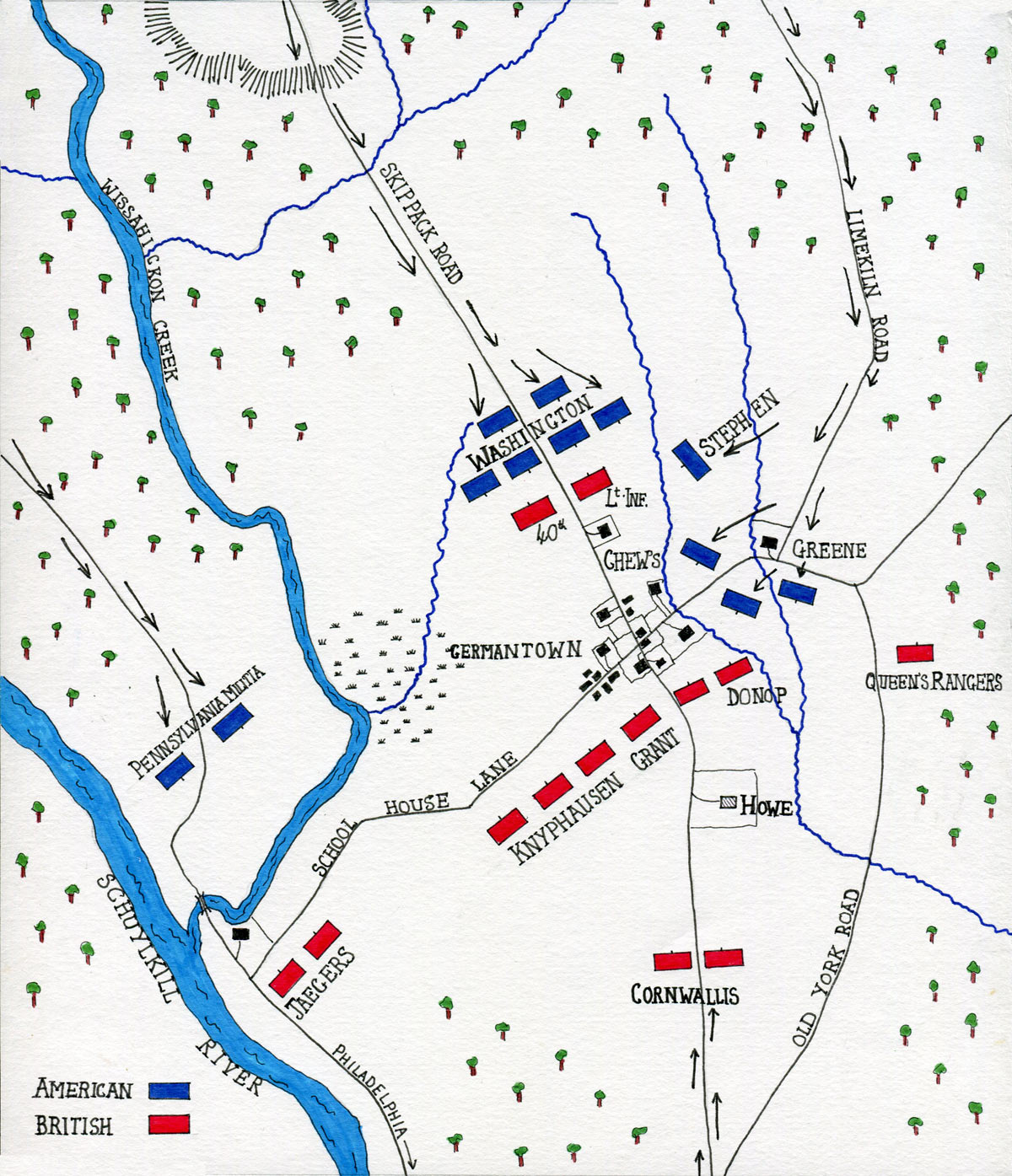

His plan called for four separate columns to converge on the British position at Germantown. The two flanking columns were composed of 3,000 militia, while the centre-left, under Nathanael Greene, the centre-right under John Sullivan, and the reserve under Lord Stirling were made up of regular troops.

The ambition behind the plan was to surprise and destroy the British force, much in the same way as Washington had surprised and decisively defeated the Hessians at Trenton. In Germantown, Howe had his light infantry and the 40th Foot spread across his front as pickets.

In the main camp, Wilhelm von Knyphausen commanded the British left, while Howe himself personally led the British right.

A heavy fog caused a great deal of confusion among the approaching Americans. After a sharp contest, Sullivan’s column routed the British pickets.

Unseen in the fog, around 120 men of the British 40th Foot barricaded the Chew Mansion. When the American reserve moved forward, Washington made the erroneous decision to launch repeated assaults on the position, all of which failed with heavy casualties.

Penetrating several hundred yards beyond the mansion, Sullivan’s wing became dispirited, running low on ammunition and hearing cannon fire behind them. As they withdrew, Anthony Wayne‘s division collided with part of Greene’s late-arriving wing in the fog.

Mistaking each other for the enemy, they opened fire, and both units retreated. Meanwhile, Greene’s left-centre column threw back the British right. With Sullivan’s column repulsed, the British left outflanked Greene’s column.

The two militia columns had only succeeded in diverting the attention of the British, and had made no progress before they withdrew.

Despite the defeat, France, already impressed by the American success at Saratoga, decided to lend greater aid to the Americans.

Howe did not vigorously pursue the defeated Americans, instead turning his attention to clearing the Delaware River of obstacles at Red Bank and Fort Mifflin.

After unsuccessfully attempting to draw Washington into combat at White Marsh, Howe withdrew to Philadelphia. Washington, his army intact, withdrew to Valley Forge, where he wintered and re-trained his forces.

Contents

[hide]

Background[edit]

The Philadelphia campaign had begun badly for the Americans. The Continental Army had suffered a string of defeats at Brandywine, and at Paoli, leaving the city of Philadelphia defenseless.

Charles Cornwallis subsequently seized Philadelphia for the British on September 26, 1777, dealing a blow to the revolutionary cause. Howe left a garrison of 3,462 men to defend the city, moving the bulk of his force north, some 9,728 men, to the outlying community of Germantown.[3]

With the campaigning season drawing to a close, Howe determined to locate and destroy the main American army. Howe established his headquarters at the Stenton Mansion, the former country home of James Logan.

Despite having suffered successive defeats, Washington saw an opportunity to entrap and decisively defeat the divided British army.

He resolved to attack the Germantown garrison, as the last effort of the year before entering winter quarters. His plan called for a complex, ambitious assault; four columns of troops were to assail the British garrison from different directions, at night, with the goal of creating a double-envelopment.

Washington’s hope was that the British would be surprised and overwhelmed much how the Hessians were at Trenton.

British positions[edit]

Germantown was a hamlet of stone houses, spreading from what is now known as Mount Airy on the north, to what is now Market Square in the south.[6]

Extending southwest from Market Square was Schoolhouse Lane, running 1.5 miles (2.4 km) to the point where Wissahickon Creek emptied from a steep gorge, into the Schuylkill River.

Howe had established his main camp along the high ground of Schoolhouse and Church lanes.

The western wing of the camp, under the command of Hessian general Wilhelm von Knyphausen, had a picket of two Jäger battalions, positioned on the high ground above the mouth of the Wissahickon to the far left.

A brigade of Hessians, and two brigades of British regulars camped along Market Square. East of the Square, two British brigades under the command of General James Grant had encamped, with two squadrons of dragoons, and the 1st battalion of Light Infantry.

The Queen’s Rangers, a unit of loyalist Americans recruited from New York, covered the right flank.

American advance

After dusk on October 3, the American force began the 16 miles (26 km) march southward toward Germantown in complete darkness.

To differentiate friend from foe in the darkness, the troops were instructed to put a piece of white paper in their hats to mark them out.[7]

The Americans remained undetected by the Jäger pickets, and the main British camp was, subsequently, unaware of the American advance.

For the Americans, it seemed their attempt to repeat their victory at Trenton was on the road to success. However, the darkness made communications between the American columns extremely difficult, and progress was far slower than expected.

At dawn, most of the American forces had fallen too short of their intended positions, losing the element of surprise they otherwise enjoyed.

The Pennsylvania Militia, led by Brigadier General John Armstrong Sr., advanced down the Manatawny Road(Ridge Avenue) to the confluence of the Wissahickon Creek and Schuylkill River.

There on the cliffs opposite General Knyphausen‘s Hessian encampment, the militia set up their artillery and began a desultory fire until withdrawing back up the Manatawny road.

Armstrong’s Brigade played no further part in the battle. The three remaining American columns continued their advance.

One column, under the command of General John Sullivan moved down Germantown Road. A column of New Jersey militia under Brigadier General William Smallwood moved down Skippack Road to Whitemarsh Church Road, and from there to Old York Road to attack the British right.

General Nathanael Greene‘s column, consisting of Greene’s, General Adam Stephen‘s divisions and General Alexander McDougall‘s brigade, moved down Limekiln Road.

Battle

A thick fog[8] clouded the battlefield throughout the day, greatly hampering coordination. The vanguard of Sullivan’s column, upon Germantown Road, opened fire upon the British pickets on Mount Airy, just after sunrise at 05:00.

The British pickets fired their cannon in alarm, and resisted the American advance. Howe rode forward, thinking they were being attacked by foraging or skirmishing parties, and ordered his men to hold their ground.

It took a substantial part of Sullivan’s division to finally overwhelm the British pickets, and drive them back into Germantown.

Howe, still believing his men were facing only light opposition, called out; “For shame, Light Infantry! I never saw you retreat before! Form! Form! It is only a scouting party!”

Just then, three American guns came into action, opening fire with grapeshot. Howe and his staff quickly withdrew out of range.

Several British officers were shocked to see their own soldiers rapidly falling back before the enemy attack. One British officer later described the number of attacking Americans as “overwhelming”.[9]

Cut off from the main force, Colonel Musgrave, of the British 40th Regiment of Foot, ordered his six companies of troops, around 120 men, to barricade and fortify the stone house of Chief Justice Chew, called Cliveden.

The American troops launched a determined assault against Cliveden, however, the outnumbered defenders repulsed their attempts, inflicting heavy casualties.

Washington called a council of war to decide how to deal with the fortification. Some of his subordinates favoured bypassing Clivden entirely, leaving a regiment behind to besiege it. However, Washington’s artillery commander, Brigadier General Henry Knox, advised it was unwise to allow a fortified garrison to remain under enemy control in the rear of a forward advance. Washington concurred.

General William Maxwell’s brigade, which had been held in reserve, was brought forward to storm Cliveden. Knox positioned four 3-pound cannon out of musket range to bombard the mansion.

However, the thick walls of Cliveden withstood the bombardment from the light field guns. The Americans launched a second wave of infantry assaults, all of which were repulsed with heavy losses.

The few Americans who managed to get inside the mansion were shot or bayoneted. It was becoming clear to the Americans that Cliveden was not going to be taken easily. Among this assault was Lieutenant John Marshall of the Virginia Line, the future Chief Justice of the United States, who was wounded during the attack.

Prior to Maxwell’s futile attack against Cliveden, Sullivan’s division advanced beyond in the fog. Sullivan deployed Brigadier General Thomas Conway‘s brigade to the right, and Brigadier General Anthony Wayne‘s brigade to the left before advancing on the British centre-left.[10]

The 1st and 2nd Maryland Brigades of Sullivan’s column paused frequently to fire volleys into the fog. While the tactic was effective in suppressing enemy opposition, his troops rapidly ran low on ammunition.

Wayne’s brigade to the left of the road moved ahead, and became precariously separated from Sullivan’s main line. As the Americans launched their attack on Cliveden, Wayne’s brigade heard the disquieting racket from Knox’s artillery pieces to their rear.

To their right, the firing from Sullivan’s men died down as the Marylanders ran low on ammunition. Wayne’s men began to panic in their apparent isolation, and so he ordered them to fall back.

Sullivan was subsequently forced back, although the regiments fought a stubborn rearguard action. Since the British units pursuing them were redirected to fight Greene’s column, Sullivan’s men fell back in good order.[11]

Meanwhile, Nathanael Greene’s column on Limekiln Road had finally caught up with the bulk of the Americans at Germantown.

Greene’s vanguard engaged the British pickets at Luken’s Mill, driving them back after a savage skirmish. The fog that clung to the field was compounded by palls of smoke from the cannon and musket fire, throwing Greene’s column into disarray and confusion.

One of Greene’s brigades, under Brigadier General Adam Stephen, veered off-course and began following Meetinghouse Road, instead of rendezvousing at Market Square with the rest of Greene’s troops. The wayward brigade collided with Wayne’s brigade, and mistook them for redcoats.

The two American brigades opened fire on each other in the fog, causing both to flee. The withdrawal of Wayne’s New Jersey Brigade, having suffered heavy losses attacking Cliveden, left Conway’s right flank exposed.

To the north, an American column led by McDougall came under attack by the Loyalist troops of the Queen’s Rangers, and the Guards of the British reserve.

After a brutal contest, McDougall’s brigade was forced to retreat, having suffered heavy losses. Despite the reversal in fortune, the Continentals were still convinced of a possible victory.

The 9th Virginia Regiment of Greene’s column launched a determined attack on the British lines as planned, managing to break through and capturing a number of prisoners. However, they were soon surrounded by two arriving British brigades under Cornwallis.

Cornwallis then launched a counter-charge, cutting off the Virginians completely, forcing them to surrender. Greene, upon learning of the main army’s defeat and withdrawal, realised he stood alone against Howe’s entire army, and so withdrew.

The primary attacks on the British and Hessian camp had all been repulsed with heavy casualties. Washington ordered Armstrong and Smallwood’s men to withdraw. Maxwell’s brigade, still having failed to capture Cliveden, was forced to fall back.

Howe ordered a pursuit, harrying the retreating Americans for some 9 miles (14 km), though he did not follow up on his victory.

The pursuing British forces were finally forced to retire in the face of resistance from Greene’s infantry, Wayne’s artillery, and a detachment of dragoons, as well as the coming of the night.

Casualties

Grave stone in upper burrying ground.[12]

Of the 11,000 men Washington led into battle, 30 officers and 122 men were killed, and 117 officers and 404 men were wounded.[13]

According to a Hessian staff officer, some 438 had been taken prisoner by the British, including Colonel George Mathews and the entire 9th Virginia Regiment.[13][14]

Brigadier General Francis Nash, whose North Carolina brigade covered the American retreat, had his left leg taken off by a cannonball, and died on October 8 at the home of Adam Gotwals.

His body was interred with military honours on October 9 at the Mennomite Meetinghouse in Towamencin.[15] Major John White, who was shot at Cliveden, died on October 10.[16]

Lieutenant-Colonel William Smith, who was wounded carrying the flag of truce to Cliveden, also died from his wounds.[16] In total, 57 Americans, over one-third of all those killed in the battle, died in the attack on Cliveden.[17]

British casualties in the battle were 71 killed, 448 wounded and 14 missing, only 24 of whom were Hessians.[5]

British officers killed in action include Brigadier General James Agnew and Lieutenant-Colonel John Bird. Lieutenant-Colonel William Walcott of the 5th Regiment of Foot was mortally wounded, and later died.[18]

Wyck House served as a hospital during the battle.

Analysis[edit]

Washington’s ambitious plan failed for several factors:

- Washington mistakenly believed his troops were sufficiently trained and experienced to launch such a complicated, coordinated assault.[19]

- Success of the plan required constant communication between the many columns of his army and precise timing. Communication was lacklustre because of the night march, and it was further handicapped by the fog.

- When the British 40th Foot put up stubborn resistance, Stephen disobeyed orders and attempted to assail the Chew House. All attempts were repulsed. Stephen was later court-martialed and cashiered from military service after evidence surfaced that he was intoxicated during the battle.[20]

Washington had intended for his attack to be a second Trenton. Had everything gone according to plan, Washington may have trapped and destroyed a second major British force. Coupled with Burgoyne’s defeat at Saratoga, the defeat of Howe at Germantown could have compelled Lord North and the British government to sue for peace.[21]

Aftermath[edit]

The battle was a limited strategic success for the British, but the long-term strategic consequences favoured the Americans. Howe had, once again, failed to follow up on his success and allowed Washington to escape with his army, leading to their encampment at Valley Forge.

The battle in particular made a strong impression upon the French court that the Americans would prove worthy allies. Sir George Otto Trevelyan, in Volume IV of his History of the American Revolution, concluded that although the battle had unquestionably been a defeat for the Americans, it was of “great and enduring service to the American cause”. In particular, the engagement persuaded the Comte de Vergennes to vouch for the United States against Britain.[22] He continues:

| “ | That the battle had been fought unsuccessfully was of small importance when weighed against the fact that it been fought at all. Eminent generals, and statesmen of sagacity, in every European Court were profoundly impressed by learning that a new army, raised within the year, and undaunted by a series of recent disasters, had assailed a victorious enemy in his own quarters, and had only been repulsed after a sharp and dubious conflict. | ” |

John Fiske, in The American Revolution (1891), wrote:[21]

| “ | …The genius and audacity shown by Washington, in thus planning and so nearly accomplishing the ruin of the British army only three weeks after the defeat at the Brandywine, produced a profound impression upon military critics in Europe. Frederick of Prussia saw that presently, when American soldiers should come to be disciplined veterans, they would become a very formidable instrument in the hands of their great commander; and the French court, in making up its mind that the Americans would prove efficient allies, is said to have been influenced almost as much by the battle of Germantown as by the surrender of Burgoyne. | ” |

Trivia[edit]

Eight Army National Guard units (103rd Eng Bn,[23] A/1-104th Cav,[24] 109th FA,[25] 111th Inf,[26] 113th Inf,[27] 116th Inf,[28]175th Inf[29] and 198th Sig Bn[30]) and one active Regular Army Field Artillery battalion (1-5th FA)[31] are derived from American units that participated in the Battle of Germantown. There are only thirty currently existing units in the U.S. Army with lineages that go back to the colonial era.

On October 6, there was a brief cease-fire. A little terrier that was identified from its collar as belonging to General Howe was formally transferred from Washington’s camp to Howe’s under a flag of truce. The little terrier that had been found wandering on the battlefield was brought to Washington, who had the dog fed, cleaned and brushed before being returned to Howe.[32][33]