Category: Uncategorized

WWII Trench Shotgun

He came from a line of Philadelphia aristocrats and started life as a spindly, gawky, withdrawn kid who lacked any kind of ambition. by rights, the young blue blood should have been a banker or a doctor or a minister, but there was a renegade gene in his makeup that caused him to love the outdoors: “in very early life i seem to have formed a desire to wander off by myself into unfrequented country.” it was a desire that would give form to a remarkable life.

He became a career soldier and, as a young officer, was fond of vanishing for months into unmapped wilderness, living off what he could shoot or catch. He became an expert outdoorsman and a superb marksman. He wrote about all of it; his first article was published in 1901 and he remained a prolific writer until his death in 1961. His name was Townsend Whelen. His friends called him “Townie,” and there has never been anyone else like him. If there ever was an “ideal” outdoorsman and hunter, that person breathed in the form of Townsend Whelen.

A Boy of Retiring Disposition

Whelen was born on March 6, 1877, and grew into a shy youngster who was happiest by himself. He might have remained so, but in 1891, at the age of 13, his life changed. His father gave him a Remington rolling block .22, and the gawky kid taught himself to shoot. He was soon beating grown men and won his first rifle match two years later. It was to be the first of many. Whelen lived in the outdoors, but at the center of his life was always the rifle.

A second change came in 1895 when he went to see an “exhibition of strength” put on by Eugene Sandow, the Arnold Schwarzenegger of his time. Whelen was inspired and began exercising fanatically. Within a year he gained 30 pounds of muscle. And then he did something very odd for a young man of his refined background: He enlisted as a private in the Pennsylvania National Guard.

Gone for a Solider

After three years, Whelen was a sergeant. In 1898, the Spanish-American War began and his unit was federalized. Within months he was promoted to regimental sergeant major, a post normally reserved for noncoms of at least 15 years’ experience. A few months after that, Whelen was commissioned a second lieutenant.

Though his unit never saw action, he now knew what he wanted to do with his life and applied for a commission in the Regular Army. But it would take a year until the next competitive exams would be given, and so he quit his job, resigned his reserve commission, and headed for the wilds of British Columbia, which at that time offered the best big-game hunting in North America.

“I gathered a little outfit which consisted of my .40/72 Winchester rifle, a .30/30 Winchester Model 94, the necessary ammunition, a light tarp 8×11 feet which I made, a pair of Army blankets and a poncho, a set of nested camp kettles, and practically nothing else.

“At Ashcroft (British Columbia) I bought a saddle horse for $25, two pack horses for $15 each, a stock saddle for $25, two sawbuck saddles for $5, and $25 worth of grub. An old prospector showed me how to pack the horses and throw the diamond hitch…. The next morning I started out over the Telegraph Trail, bound for northern British Columbia.”

In the town of Lillooet he met a stroke of luck in the form of “Bones” Andrews, an experienced wilderness hand and a prospector who took a shine to Whelen and offered to guide him into game country. On Andrews’ advice, Whelen bought a Free Miner’s Certificate, which permitted him to kill as much game as he needed for food.

Andrews was not only a good guide but a good teacher. In particular, he taught Whelen how to cook over an open campfire, using a cross stick held by two forked sticks with a hooked stick as a potholder. A pit under a forelog served as a baking oven.

Whelen lived in the wilderness for several months, taking game of all typ and recording what he did. He even managed to conduct some business on the return trip, buying two groundhog robes from Chiloctin Indians he met on the trail and selling them at a profit in New York City.

Photographs of Whelen taken around this time show a barrel-chested, ramrod-straight young man of over 6 feet, a curved-stem pipe dangling from his lips, dressed in a campaign hat (we call it a Smokey Bear hat), fringed buckskin shirt (later replaced by Army-issue flannel), jodhpurs, and calf-high moccasins. He carried a rifle and a rucksack always, and sometimes a handgun.

Whelen was a frugal man who traveled light. He made his own gear when he could and did not carry an ounce more than he needed (his complete backpacking outfit weighed only 12 pounds). His camps always looked the same: a blanket roll beneath a lean-to tarp (which he preferred to a tent) and a pot suspended above a cooking fire built just as Bones Andrews had taught him.

The Regular

He came from a line of Philadelphia aristocrats and started life as a spindly, gawky, withdrawn kid who lacked any kind of ambition. by rights, the young blue blood should have been a banker or a doctor or a minister, but there was a renegade gene in his makeup that caused him to love the outdoors: “in very early life i seem to have formed a desire to wander off by myself into unfrequented country.” it was a desire that would give form to a remarkable life.

He became a career soldier and, as a young officer, was fond of vanishing for months into unmapped wilderness, living off what he could shoot or catch. He became an expert outdoorsman and a superb marksman. He wrote about all of it; his first article was published in 1901 and he remained a prolific writer until his death in 1961. His name was Townsend Whelen. His friends called him “Townie,” and there has never been anyone else like him. If there ever was an “ideal” outdoorsman and hunter, that person breathed in the form of Townsend Whelen.

A Boy of Retiring Disposition

Whelen was born on March 6, 1877, and grew into a shy youngster who was happiest by himself. He might have remained so, but in 1891, at the age of 13, his life changed. His father gave him a Remington rolling block .22, and the gawky kid taught himself to shoot. He was soon beating grown men and won his first rifle match two years later. It was to be the first of many. Whelen lived in the outdoors, but at the center of his life was always the rifle.

A second change came in 1895 when he went to see an “exhibition of strength” put on by Eugene Sandow, the Arnold Schwarzenegger of his time. Whelen was inspired and began exercising fanatically. Within a year he gained 30 pounds of muscle. And then he did something very odd for a young man of his refined background: He enlisted as a private in the Pennsylvania National Guard.

Gone for a Solider

After three years, Whelen was a sergeant. In 1898, the Spanish-American War began and his unit was federalized. Within months he was promoted to regimental sergeant major, a post normally reserved for noncoms of at least 15 years’ experience. A few months after that, Whelen was commissioned a second lieutenant.

Though his unit never saw action, he now knew what he wanted to do with his life and applied for a commission in the Regular Army. But it would take a year until the next competitive exams would be given, and so he quit his job, resigned his reserve commission, and headed for the wilds of British Columbia, which at that time offered the best big-game hunting in North America.

“I gathered a little outfit which consisted of my .40/72 Winchester rifle, a .30/30 Winchester Model 94, the necessary ammunition, a light tarp 8×11 feet which I made, a pair of Army blankets and a poncho, a set of nested camp kettles, and practically nothing else.

“At Ashcroft (British Columbia) I bought a saddle horse for $25, two pack horses for $15 each, a stock saddle for $25, two sawbuck saddles for $5, and $25 worth of grub. An old prospector showed me how to pack the horses and throw the diamond hitch…. The next morning I started out over the Telegraph Trail, bound for northern British Columbia.”

In the town of Lillooet he met a stroke of luck in the form of “Bones” Andrews, an experienced wilderness hand and a prospector who took a shine to Whelen and offered to guide him into game country. On Andrews’ advice, Whelen bought a Free Miner’s Certificate, which permitted him to kill as much game as he needed for food.

Andrews was not only a good guide but a good teacher. In particular, he taught Whelen how to cook over an open campfire, using a cross stick held by two forked sticks with a hooked stick as a potholder. A pit under a forelog served as a baking oven.

Whelen lived in the wilderness for several months, taking game of all typ and recording what he did. He even managed to conduct some business on the return trip, buying two groundhog robes from Chiloctin Indians he met on the trail and selling them at a profit in New York City.

Photographs of Whelen taken around this time show a barrel-chested, ramrod-straight young man of over 6 feet, a curved-stem pipe dangling from his lips, dressed in a campaign hat (we call it a Smokey Bear hat), fringed buckskin shirt (later replaced by Army-issue flannel), jodhpurs, and calf-high moccasins. He carried a rifle and a rucksack always, and sometimes a handgun.

Whelen was a frugal man who traveled light. He made his own gear when he could and did not carry an ounce more than he needed (his complete backpacking outfit weighed only 12 pounds). His camps always looked the same: a blanket roll beneath a lean-to tarp (which he preferred to a tent) and a pot suspended above a cooking fire built just as Bones Andrews had taught him.

The Regular

In May of 1902, Whelen returned to Philadelphia and was informed that no more than 50 candidates would be allowed to take the exam for a Regular Army commission. His father, through a friend, got Whelen an interview with President Theodore Roosevelt who pronounced him “the type of young man I want to see in the Army.” Whelen made the list.

At Governor’s Island, New York, he underwent an exhaustive weeklong series of physical and written exams and finished second. But two weeks later he was informed that he had failed the physical test because of “insufficient chest development.” Whelen, who at the time had a 44-inch chest and a 29-inch waist, was frantic. He went to Washington to plead his case directly with Elihu Root, the secretary of war. When Whelen asked (essentially) “What the hell?” Root told him not to worry, that he would come out all right. And he did. Whelen was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the U.S. Army.

In 1915, as the Panama Canal neared completion, the Army was given the job of defending it, and Whelen, now a captain, was assigned to the 29th Infantry Regiment, which became part of the Canal Zone garrison.

(At this point, a word about the Panama jungle is in order. After World War II, when the Army was looking for a truly loathsome, horrible rain forest to serve as its jungle survival school, it picked Panama’s. I have spoken with Vietnam vets who claim they never saw anything in Southeast Asia that was half as bad.)

The 29th Infantry was assigned to defend a chunk of unmapped real estate that was, as far as anyone knew, uninhabitable, and how you would defend such country, no one had a clue.

Capt. Whelen took it upon himself to find out. On weekends he set out to explore, taking only a rifle and a rucksack, always alone because: “I knew of no one who would not be more of a hindrance than a help. I had no fear of getting lost, for I knew that my faculty of keeping a mind map would serve me as well here as it always had in other unfamiliar country I had been penetrating all my life. And I discredited all the stories of snakes, reptiles, insects, and wild beasts.

“I soon found that the only way to keep located was to make a continuous map, and¿¿¿that it was necessary to keep the map up to date every 200 yards. I made the map on a little sheet of celluloid which I carried in my shirt pocket-celluloid because paper would not stand the sweat. Every hour I would copy the sketch off the celluloid on to the big sheet in my rucksack.” For Whelen, hardship and danger were too trivial to mention. Given his rifle and rucksack and pipe, a lean-to and a bedroll, he was as at ease in the Panama rain forest as he was in the wilds of Alberta. Everything he saw fascinated him.

When he felt himself to be at home in the jungle, Whelen trained his company to live in it, and they set the pattern for the rest of the 29th Regiment and, most likely, the U.S. Army itself.

In 1917, when the United States entered World War I, Whelen had compiled a distinguished record and had attracted the attention of senior officers. He was assigned to the Army General Staff and spent the war inspecting camps and developing training programs.

After the war, lacking combat experience and having developed an intense interest in small-arms development, he transferred from the Infantry to Ordnance, where he would serve until his retirement in 1936. But his heart remained with the doughboys. Long after he took off the uniform for the last time, he wrote: “I would chuck all the work I have done, all the small success I have made, if I could go back tomorrow as Captain in command of Company F, 29th Infantry.”

Whelen became commanding officer at the Frankford Arsenal (where, in 1804, his great-great-grandfather, Commissary General of the Army Israel Whelen, had outfitted the Lewis and Clark Corps of Discovery) and director of research and development at the Springfield Armory. These two assignments put him in daily contact with not just his own highly skilled gunsmiths but with their civilian counterparts. Whelen learned from all of them.

He hunted all his life, taking his first deer in 1892 and his last 66 years later. Whelen’s lifetime big-game bag totaled 110 head. Everything he learned went on paper. He wrote at least half a dozen books and over the years was a regular columnist for Field & Stream, Sports Afield, Outdoor Life, The American Rifleman, and Guns & Ammo.

Confused Moose, Plummeting Goat

Whelen hunted all over Canada, throughout the Rocky Mountains, and in the Adirondacks-wherever there was real wilderness and deep forests. He left no records of what he considered close calls, but others might view the stories differently. On one occasion in the Canadian Rockies, he had come down off a sheep mountain. Lying down at a stream to get a drink, he heard a sound like someone hitting a tree with a baseball bat, then the sound of thundering hooves, then an ominous silence. It was a bull moose in the throes of whatever afflicts bull moose, standing over him. One more step and he would have trod on Whelen’s feet.

Whelen rolled over and aimed his rifle at the moose, just in case. They remained that way for perhaps 10 seconds until finally Whelen inquired in his best Army terminology what the moose thought he was doing there. The moose almost fell over backward and cleared 50 feet in three jumps. Then he stood, horning the bushes, grunting nonstop, with Whelen grunting back at him. Finally Whelen got his drink and went back to camp, leaving the moose to amuse himself as best he could.

(There is a photograph taken on this trip that shows Whelen packing out the head and cape of a different bull moose-roughly 150 pounds. He does not looly, the U.S. Army itself.

In 1917, when the United States entered World War I, Whelen had compiled a distinguished record and had attracted the attention of senior officers. He was assigned to the Army General Staff and spent the war inspecting camps and developing training programs.

After the war, lacking combat experience and having developed an intense interest in small-arms development, he transferred from the Infantry to Ordnance, where he would serve until his retirement in 1936. But his heart remained with the doughboys. Long after he took off the uniform for the last time, he wrote: “I would chuck all the work I have done, all the small success I have made, if I could go back tomorrow as Captain in command of Company F, 29th Infantry.”

Whelen became commanding officer at the Frankford Arsenal (where, in 1804, his great-great-grandfather, Commissary General of the Army Israel Whelen, had outfitted the Lewis and Clark Corps of Discovery) and director of research and development at the Springfield Armory. These two assignments put him in daily contact with not just his own highly skilled gunsmiths but with their civilian counterparts. Whelen learned from all of them.

He hunted all his life, taking his first deer in 1892 and his last 66 years later. Whelen’s lifetime big-game bag totaled 110 head. Everything he learned went on paper. He wrote at least half a dozen books and over the years was a regular columnist for Field & Stream, Sports Afield, Outdoor Life, The American Rifleman, and Guns & Ammo.

Confused Moose, Plummeting Goat

Whelen hunted all over Canada, throughout the Rocky Mountains, and in the Adirondacks-wherever there was real wilderness and deep forests. He left no records of what he considered close calls, but others might view the stories differently. On one occasion in the Canadian Rockies, he had come down off a sheep mountain. Lying down at a stream to get a drink, he heard a sound like someone hitting a tree with a baseball bat, then the sound of thundering hooves, then an ominous silence. It was a bull moose in the throes of whatever afflicts bull moose, standing over him. One more step and he would have trod on Whelen’s feet.

Whelen rolled over and aimed his rifle at the moose, just in case. They remained that way for perhaps 10 seconds until finally Whelen inquired in his best Army terminology what the moose thought he was doing there. The moose almost fell over backward and cleared 50 feet in three jumps. Then he stood, horning the bushes, grunting nonstop, with Whelen grunting back at him. Finally Whelen got his drink and went back to camp, leaving the moose to amuse himself as best he could.

Yes sir!

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)

He’s a national icon and hero to many a politician, but much of what people know about Winston Churchill’s life concerns his later years in politics.

In contrast, what follows is a look at Churchill’s earlier military service by historian and writer Jacob F Field, whose book ‘D-Day in Numbers’ featured in our coverage of D-Day 75.

This coincides with the publication of his new book, ‘The Eccentric Mr Churchill’, which you can get here.

Article by Jacob F Field

Winston Churchill’s long involvement with the British Army did not begin well.

His father had pushed him towards a military career because he believed he was not bright enough to study law. It took Winston three attempts to pass the entrance exam for Sandhurst and when he did pass, in August 1893, he did not get enough marks to qualify for training as an infantry officer, so was placed into the cavalry.

This irritated his father because cavalry cadets required an additional £200 of kit per year.

Luckily, as a result of other candidates dropping out, Winston was offered an infantry training place after all and he passed out with honours in December 1894, finishing eighth out of 150 classmates.

He was supposed to serve in the prestigious 60 Rifles but Winston was more attracted to the glamour of the cavalry, where promotions tended to be quicker and his small status would not be an issue. As such, Winston switched to 4 (Queen’s Own) Hussars, a socially elite regiment based in Aldershot.

However, Winston’s first taste of combat came not as a soldier, but as an observer, during the Cuban War of Independence.

In November, 1895, Winston travelled across the Atlantic, arriving in Havana via New York and Florida. He was given permission to join the Spanish forces. Officially a ‘guest’, he could only use his weapons in self-defence.

Winston spent seven weeks in Cuba, and experienced being under enemy fire for the first time, as well as witnessing a pitched battle.

(In fact, the US and Britain had a brief dispute over the Venezuelan border that year, before the US went to war with Spain in 1898, invading Cuba in the process).

The next trip abroad would be to India; in October 1896 Winston arrived at Bangalore, the new base for 4 Hussars.

He was largely restless and unhappy there; his official duties were undemanding, taking only three hours per day and usually completed by 10.30am. His main priorities appeared to be playing polo (he was part of the victorious team in the Inter-Regimental Polo Tournament in Hyderabad), reading, rose-gardening and collecting butterflies (sadly his terrier ate the sixty-five species he had gathered).

Winston was also unhappy about the officers’ mess, complaining it needed new carpet, cleaner tablecloths and better-quality cigarettes. His attitude annoyed many of his fellow officers, and culminated in him being squashed under a sofa in the mess (he escaped.)

Winston would experience some combat, but once again it was not as a soldier. This time it was in the North West Frontier Province, on the border between British India and Afghanistan.

The region was inhabited by Pashtun tribes who often rebelled against British forces. In July 1897 they attacked the British garrison in Malakand. A field force was dispatched to stamp out the uprising.

Winston managed to join the Bengal Infantry, which was part of the field force, but he was attached as a journalist. He spent six weeks with them, filing fifteen dispatches for the Daily Telegraph.

He came under fire ten times, and was mentioned in dispatches for bravery.

During this time Winston developed a taste for whisky; at the time it was out of fashion in England and on the few occasions he had tried it he had not enjoyed the smoky taste. However, it was the only drink available in Malakand so Winston learned to appreciate it by the end of the campaign, and it became his habitual beverage of choice.

In March, 1898, an Anglo-Egyptian army was sent out to defeat the Sudanese Mahdists, followers of the religious leader Muhammad Ahmad, who proclaimed himself the ‘Mahdi’, a messianic figure who would redeem Islam.

As Britain had not fought a major war in over decade, every soldier in the Empire wanted to join the expedition.

Winston was no different. From India, he requested a transfer to a regiment bound for Sudan, 21 Lancers.

This was approved by the War Office but rejected by Herbert Kitchener, the leader of the expedition.

Winston took leave to return home to lobby for the transfer, arriving in London in June. Friends and family spoke up for him, and even the prime minister supported his appeal.

Kitchener, the son of an Irish army officer, still refused, possibly because he resented the young aristocrat’s entitlement and social connections.

Winston finally forced his way into 21 Lancers when Sir Evelyn Wood, a high-ranking general in England who had authority over appointments to the regiment, named him as the replacement for an officer who died in Sudan that July. Winston was with his new regiment by August.

He had arranged to write reports for the Morning Post to finance the trip, as the War Office would not pay his expenses (as well as declining any liability if he was wounded or killed.)

On 2 September Winston took part in the decisive engagement of the war, the Battle of Omdurman.

Kitchener’s forces, though outnumbered two-to-one, were armed with modern artillery, rifles and machine guns. These new weapons cut through the Mahdist lines, killing thousands.

When they retreated, Kitchener sent 21 Lancers, including Winston, to pursue.

After the battle, wounded Mahdists were left to die or shot and bayoneted where they lay. This was approved by Kitchener, shocking Winston, who criticised the decision in print.

He returned to London in October before travelling back to India that December.

Shortly afterwards the British Army instituted a regulation forbidding serving officers from simultaneously working as war correspondents. This contributed to Winston resigning his commission so he could pursue writing, as well as politics.

Winston left India for the final time in March 1899; that July he stood as a Conservative candidate in the Oldham by-election but was unsuccessful.

In October, 1899, war erupted in South Africa between Britain and the independent Boer Republics of Orange Free State and Transvaal.

Winston would cover the conflict for the Morning Post but his journalistic enterprises were interrupted on 15 November, when his train was ambushed and derailed by the Boers. Winston was captured and held at a POW camp in Pretoria, the capital of Transvaal.

On 12 December, he scaled the walls and escaped, stowing away on a freight train.

Without any supplies, he disembarked at the mining town of Witbank to look for food. By this time he was wanted dead or alive and there was a £25 bounty on his head.

Fortunately, Winston came across the home of an English mine manager who agreed to feed and shelter him.

He was hidden first down a mine, then in an office, and, after six days, was placed aboard a train hidden in a consignment of wool bound for Portuguese East Africa (modern Mozambique), where he arrived on 21 December.

Winston then sailed to Durban and joined the South African Light Horse regiment as a lieutenant. He took part in the Relief of Ladysmith before joining in the capture of Pretoria.

After the fall of Pretoria, the war transitioned to a guerrilla conflict between Boer commandos and British and Commonwealth forces that went on until May 1902.

Meanwhile, Winston had left South Africa and on 20 July 1900 arrived home.

Reports of his escape had made him a national celebrity, helping him to be elected MP for Oldham that October.

Whilst pursuing his career as a politician and writer, Churchill decided to volunteer for a yeomanry regiment, and in January, 1902, Winston joined the Queen’s Own Oxfordshire Hussars (QOOH), as a captain. In 1905 Winston became a major in the regiment, and until 1913 commanded its Henley-on-Thames squadron.

In September, 1906, whilst still a junior minister, Winston travelled to Silesia (a region now mostly in Poland, but then part of Germany) and spent a week observing the manoeuvres of the German Imperial Army.

He stayed in Breslau (now Wrocław) and with other guests and officials and was taken by train out to the countryside to view the assembled ranks of 50,000 soldiers going through their exercises.

The evenings were spent at official banquets. Winston would even meet Kaiser Wilhelm II.

He reported that the Germans were very well-organised and disciplined, although he noted that Wilhelm had little conception of the power of modern weaponry.

The next year, Winston attended the manoeuvres of the French Army; he adored their bright uniforms and the pageantry of the occasion.

It made him a firm believer in the recently-established Entente Cordiale, an alliance that would hold steady throughout World War I, which broke out in 1914. By this time, Winston was First Lord of the Admiralty.

He still played close attention to his reserve regiment, the QOOH. Shortly after the war started he intervened to ensure they would be sent to serve on the Western Front.

The regular army did not hold them in high regard, nicknaming them the ‘Queer Objects On Horseback’ or ‘Agricultural Cavalry’.

Winston fell from power following the disaster of the Gallipoli Campaign, which he had been a major supporter of, he was forced out of the position in May 1915, and was demoted to being Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster, a post with no real power or influence.

That November, Winston resigned from government and returned to the Army, hoping to play a role in the fighting.

In December, Winston went to the Western Front for one month of training with the Grenadier Guards infantry regiment.

By the new year he was a (temporary) lieutenant-colonel commanding 6 Royal Scots Fusiliers, an infantry regiment posted at Ploegsteert (known as ‘Plug Street’ by the British) in Flanders, a fairly quiet sector at the time.

He made sure he was well-provisioned, taking with him food boxes from Fortnum & Mason, corned beef, stilton, cream, ham, sardines, dried fruit, steak pie, peach brandy and other liqueurs. He also brought a gramophone to put in the officers’ mess, as well as a portable bath.

Winston’s first major initiative was a campaign of delousing, as well as encouraging sports days and singing while marching. He then focused on building and repairing the trenches his battalion was stationed at. He proved to be popular with his men; attentive to wounded soldiers but perhaps over-lenient on disciplinary matters.

In total, Winston made thirty-six forays into No Man’s Land, often placing himself at some risk. However, with little chance of a promotion or a transfer to a more active sector Winston returned home in March.

He eventually returned to government in July 1917, serving as Minister of Munitions (a post formerly held by then PM David Lloyd George) and playing an important role in securing victory for the Allies.

Winston would carry on serving as a reserve officer until 1924, when he resigned from the Territorial Army.

By this time, the QOOH had converted into an artillery force. For much of World War II they served in England and Northern Ireland, until in October 1944 Winston, by now Prime Minister, personally requested they be sent to fight in France.

He was the regiment’s Honorary Colonel until his death, and left instructions they be given a place of distinction in the procession at his state funeral, immediately in front of his coffin.

That procession would take place on January 30, 1965, six days after Winston’s death.

For more on ‘The Eccentric Mr Churchill’, including his time in the military, read Jacob F Field’s book.

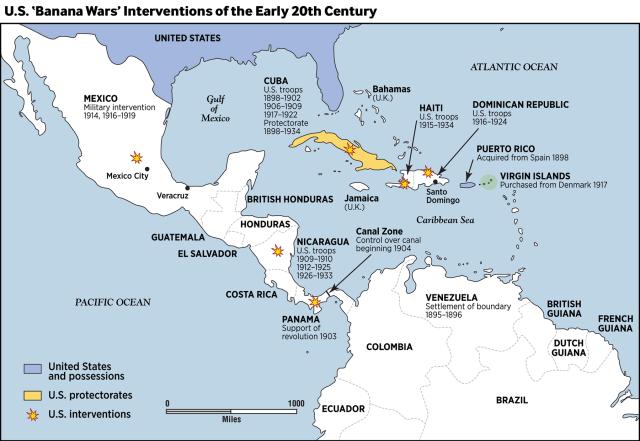

The United States’ early 20th-century military interventions in Asia and the Caribbean are important because they have us reckon with questions about the use of military/naval power abroad. These questions pertain to U.S. motivations to intervene as well as the effectiveness, cost, and consequences of intervention on the peoples and military institutions involved.

This historical drama played out in the Philippines, China, Cuba, Hispaniola, and Central America between 1898 and 1934. Although the U.S. Army played the leading role throughout much of the early interventions, it was the U.S. Marines who effectively took over these tasks in the early 1910s through the early 1930s. Doing so led them to develop their own “small wars” doctrine that ultimately enhanced the service’s flexibility. These interventions also imbued the Corps with a robust history of counterinsurgency operations that informs much of its institutional identity.

New Wars for an Expansionist Century

After the Spanish-American War, the United States became an empire in all but name. Americans’ history of westward expansion across North America culminated with the closing of the frontier in 1890. That expansionist impulse then spilled overseas to places such as Hawaii and the Philippines. Missionaries and politicians wanted to spread civilization, build roads and schools, and uplift the lives of natives in these exotic locales. U.S. produce and energy companies, however, wanted access to the natural resources of these places and native labor to extract and process them. American banks funded these ventures, even going so far as to become creditors to foreign treasuries.1

Security was a major concern, too. During the 1890s and 1910s, the empires of Great Britain, Germany, France, and Russia seized lands in Africa and Asia without much consideration to the sovereignty or wishes of native peoples. The U.S. defeat of Spain created a political vacuum in its former possessions that many Americans believed would be filled by some other power if those territories were granted full autonomy. Therefore, the McKinley administration chose to stay on in such places as the Philippines, Cuba, and Puerto Rico after the war.2

Once the United States became a power with global interests, the Navy and Marine Corps expanded. Newly acquired Pacific islands such as Hawaii, Samoa, Guam, and Wake could serve as advanced bases for coaling stations and ports that allowed the U.S. Navy to project power globally and protect maritime communications and commerce.

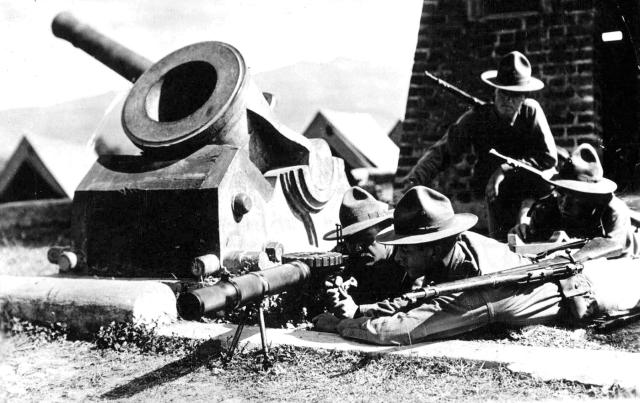

The Marine Corps began down a path with two lanes. One was advanced base seizure and defense, the operational and conceptual antecedent for the 1934 Tentative Manual for Landing Operations. Small wars, contingency operations, and counterinsurgencies comprised the other. Although early 20th-century Marines’ intellectual predilections shifted toward the former lane, they mostly operated in the latter.

Manifest Pacific Destiny?

Soon after the McKinley administration annexed the Philippines, the U.S. Army found itself embroiled in a deadly counterinsurgency. Filipino revolutionaries fought too long against Spain to trade one colonial overlord for another. Led by Emilio Aguinaldo, the resistance first waged a conventional war in early 1899 against the Army VIII Corps operating out of Manila.3

A regiment of Marines soon arrived on Luzon to aid the Army in putting down the revolt. The most notable action for the Marines involved a battalion assault of the fortified garrison at Novaleta, southwest of Cavite, in October. Soldiers and Marines soon defeated Aguinaldo’s forces in conventional operations, and the conflict morphed into a guerrilla war.

The Marines learned from the Army’s senior leaders, who had counterinsurgency experience dating back to the Civil War and Indian wars of the frontier. By 1900, the Army had developed de facto counter-guerrilla methods that balanced violent coercion with peaceful encouragement, a “carrot and stick” approach.

By 1902, it had become evident that although waging counterinsurgencies proved a great learning experience for Marines, it certainly was not a rewarding one. Marines had learned from the Army that attraction and chastisement measures needed to be wielded in proportions dictated by the situation; the situation in the Philippines was terrible.

Harsh U.S. treatment of Filipinos drew condemnation from the American press. “Forgery, deception, the violation of the laws of hospitality . . . the wanton slaughter of troops drawn up under false representations of peaceful intention, all these things, we are assured, are manly in the eyes of a soldier,” wrote one critic.4 This would not be the last time U.S. troops, Marines included, would get lambasted in the press while waging small wars overseas.

TR’s Beefed-Up Monroe Doctrine

President Theodore Roosevelt considered the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea vital to U.S. security for several reasons. Many Caribbean countries held substantial debts to European creditors. The Roosevelt administration believed that civil unrest, often fueled by political and economic strain caused by those debts, invited European intervention. This was unacceptable to TR because it violated the Monroe Doctrine that proclaimed unilaterally an end to European colonization of the Western Hemisphere.

European naval and military presence in the Caribbean threatened the isthmian canal under construction in Panama. Once completed, the canal would give maritime and naval vessels the ability to bypass the Magellan Strait. Any threat to the canal equated to a threat to trade and the U.S. Navy’s ability to concentrate its fleets in either hemisphere. Therefore, TR promulgated a “corollary” to the Monroe Doctrine that asserted the right of the United States to intervene in Latin American countries to preclude powers such as Germany from establishing bases in the region.

Under these auspices, the Navy landed Marines all over the region to protect American business and quell civil/political strife. Before U.S. entry into World War I, Marines deployed to Cuba in 1906, 1912, and 1917; the Dominican Republic in 1903, 1904, and 1916; Panama in 1903 and 1904; Nicaragua in 1912; Mexico in 1914; and Haiti in 1914 and 1915.

By 1910, the Army wanted nothing more to do with chasing insurgents in insalubrious climes. Guerrilla wars and nation-building in places such as Cuba and the Philippines had been lackluster affairs despite some successes. The Army tried to get out of intervening in Cuba in 1906 and argued against sending soldiers to China in 1911 and later to Nicaragua in 1912. Generals and chiefs of staff such as General Leonard Wood argued that sending smaller units of Marines was a more appropriate response to troubled areas in the Caribbean than sending large Army formations.5

The success the Army had in getting away from small wars stemmed from an institutional strength the Marines lacked. The Corps’ place in the defense establishment was tenuous in the early 1900s. Despite being assigned the advanced base mission in 1900 and growing from 3,000 to nearly 10,000 men between 1899 and 1912, the Marines experienced several attempts to legislate them out of existence.

The Navy attempted to remove them from its ships in 1906, and General Wood suggested the Corps be handed over to the Army. Marines regained their places on board naval vessels by 1909, but institutional vigilance remained high. Eager to prove their worth in the face of seemingly continuous threats to their existence, Marines took over the constabulary mission without any objections from the Army.

In a way, this made sense, because the Marine Corps’ size and fluid force structure made it ideal for small-scale interventions on short notice. Its organization stemmed from the Navy and U.S. government tasking Marines to guard naval yards, serve as ships’ detachments, and form a mobile force for advanced base operation and expeditionary duty while only allotting funding for 341 officers and 9,988 enlisted personnel.6

Up to 1912, Marine regiments and battalions were provisional, organized hastily when necessary and disbanded quickly afterward. Marine Corps headquarters did this by pulling Marines from various barracks and ship detachments, appointing a command staff, and designating them a temporary unit number.7

This amorphous structure confused many outsiders, but it created a fluidity that allowed the Marines to respond to their varied missions quickly. It came in handy when Marines deployed hastily to Nicaragua in 1912 and Vera Cruz, Mexico, in 1914. These were high-profile interventions, especially Vera Cruz, for which Congress awarded nine Medals of Honor to Marines, including Smedley Butler, and 47 to the Army and Navy. Except for a small force of Marines that remained in Managua, Nicaragua, to guard the legation, neither intervention necessitated long occupations.

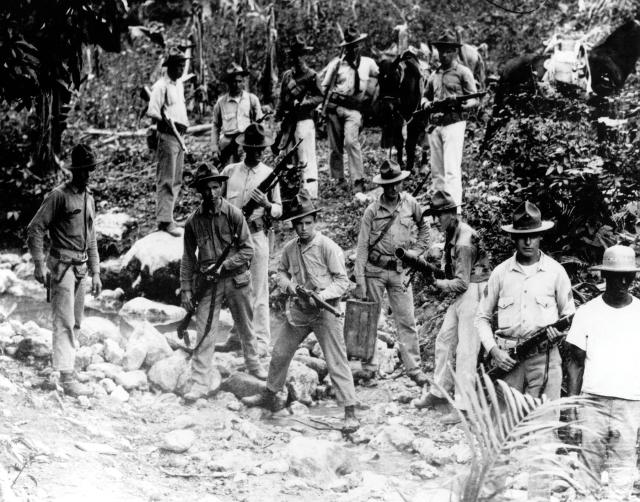

Guns to Hispaniola

Marines landed at Port-au-Prince in July 1915 after armed rebels assassinated the Haitian president and took over the government. By August, the First Provisional Brigade arrived, commanded by Colonel L. W. T. Waller along with Major Smedley Butler. Marines then went about pursuing insurgents (known colloquially as Cacos) and pacifying as much of the country as they could. Butler’s assault on Fort Rivière in November was the most dramatic combat action, ending with more than 50 insurgents killed. Marine companies soon occupied 16 Haitian towns and settled in for a long occupation.8

Marines then landed in the Dominican Republic in May 1916 after rival political factions wrested government control from President Juan Isidro Jimenes. Colonel Joseph Pendleton organized Marine units from Haiti, Cuba, and Admiral William Caperton’s warships into an expeditionary force that defeated armed Dominicans at Las Trencheras and Guayacanas and eventually took the city of Santiago. Rear Admiral Harry S. Knapp became the military governor of the country, while Pendleton and his Marines set about pacifying the countryside.

Although Haiti and the Dominican Republic were separate campaigns, Marines in both occupations drew upon what they had learned in Cuba and Panama and from working with the Army in the Philippines.9 They established native constabularies, the Gendarmerie d’Haiti and the Guardia Nacional Dominicana, with enlisted Marines serving as temporary officers. Marines used civil programs such as improving sanitation, providing basic security and medical care, and building roads as methods of attraction. Chastisement measures often took the form of combat patrols, early morning raids, the confiscation of property, and the killing of livestock.

Soon after the United States entered the Great War, Marines began using more coercive measures on Hispaniola. By the summer of 1918, insurgent activity had intensified in both Haiti and the Dominican Republic. To send as many experienced troops to France as possible, Commandant George Barnett pulled Marine companies out of Hispaniola and replaced only some of them with brand new volunteers who had joined to fight the Germans, not Haitians or Dominicans.

One commander in Haiti reported in April 1917 that the “reduction of the number of Marines in Haiti by two companies is, in my opinion, a serious mistake . . . it is necessary in my mind that we increase our influence in this Island and not weaken it.”10

In Haiti, Marines revived the old corvée labor system whereby Haitians who could not afford to pay taxes for road construction paid with their own labor. While overseeing road construction in northern Haiti in January 1919, Major Clarke H. Wells allegedly ordered illegal executions of 19 Haitian prisoners.11 This event fanned the flames of an insurgency led by Charlemagne Péralte, whom the Marines assassinated nine months later.

In the Dominican Republic, cuadillos in the eastern provinces led a grassroots resistance against foreign invasion and economic exploitation.12 Bending under the pressure, the Marines brought back the odious concentration tactics they learned from the Army by relocating Dominicans from the countryside into urban centers to separate them from insurgents.

One Dominican witness to the camps described them as people being “locked up like pigs in stockades.”13 In August and September 1918, Captain Charles F. Merkel tortured and killed Dominicans found outside the concentration areas in Seibo Province. After being arrested, Merkel, to protect the Corps’ reputation, committed suicide in his cell with a smuggled pistol.14

Marines then experienced several years of acrimony after American journalists got wind of “indiscriminate killings” in the fall of 1919. Accusations in the newspapers prompted several investigations conducted by the Navy, the Marine Corps, and the U.S. Senate, all of which found only a few substantiated instances of wrongdoing. But journals such as The Nation and papers such as the Cleveland Gazette painted the Corps as a racist institution motivated by white supremacy.15 Indeed, many Marines held overt racist attitudes against Haitians and Dominicans, which caused them to underestimate their enemy and misunderstand the causes of both insurgencies.16

Hunting the Sandinistas

Amid shifting U.S. opinions on interventions, Nicaragua would be the last of the Corps’ pre-World War II counterinsurgency operations. A Marine legation had stayed in Managua since 1912 but left in 1925. Soon after its departure, conservative-leaning General Emiliano Chamarro Vargas led a revolt against the government and precipitated a civil war. The United States supported an interim government led by Adolfo Diaz, but Mexico and Honduras supported the former liberal Vice President Juan Sacasa. An army led by liberal José Maria Moncado wreaked havoc down Nicaragua’s east coast, attacking and seizing U.S. commercial property as it went.

Marines reactivated the 2nd Marine Brigade and sent it to Nicaragua under the command of Logan Feland. While the U.S. State Department brokered a peace deal between the two factions, Marines went to work again providing security for new elections and building a Nicaraguan national guard (See “A U.S. Marine in the Guardia Nacional,” pp. 20–25.).17

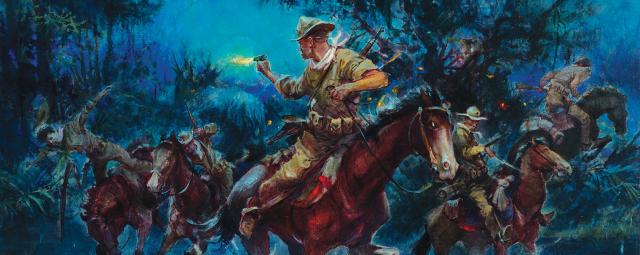

Liberal political and military leader Augusto César Sandino fought the Marines for five years. Soon-to-be-famous Marines such as Majors Samuel M. Harrington and Harold H. Utley, Captain Merritt A. Edson, First Lieutenant Hermann Hanneken (the Marine who had killed Charlemagne Péralte in Haiti), and First Lieutenant Lewis B. “Chesty” Puller pursued “Sandinistas” through the countryside with Thompson submachine guns and close-air support.

They garrisoned numerous posts around the country to pacify the surrounding areas, guarded U.S. commercial property, and continued to train and develop the Guardia Nacional. Air support, first introduced on Hispaniola, played a crucial role in reconnaissance, resupply, and direct combat support, an important precursor to the eventual Marine air-ground task force. Marine pilots used dive-bombing tactics on the Sandinistas, a methodology that would come in handy in major U.S. wars to come.

Like the Hispaniola occupations, the Nicaraguan campaign became unpopular in the United States. After the Great War, American public opinion shifted decidedly against military interventions. The Republican administrations of Warren G. Harding (1921–23), Calvin Coolidge (1923–29) and Herbert Hoover (1929–33) tended to favor restraint over further entanglements in Latin America.18 The Coolidge administration pulled Marines out of the Dominican Republic in 1924. They continued to pacify Haiti and Nicaragua until 1933 and were effectively pulled out by 1934. The Marines never caught Sandino.

‘A Perilous and Thankless Job’

The early to mid-1930s was an intellectual crossroads for the Corps. A fervent debate took place within the halls of Marine Corps schools as to the identity and future of the institution: Would it continue as a constabulary force or as an advanced base force? It became a mixture of the two—although the intellectual effort and force structuring that took place during this time reflected a clear predilection for the latter.

Many Marines wanted to get away from contingency operations. They learned all too well that waging small wars was a perilous and thankless job. In addition, with the occupations of Nicaragua and Haiti concluded, the Corps had manpower and brain power free to focus on what many wanted to be their future raison d’etre: advanced base seizure and defense. Even acting Commandant Lieutenant General John H. Russell, who commanded Marines in Haiti and the Dominican Republic, wanted to sideline the small wars mission in favor of the advanced base one.

The Navy accepted Russell’s proposal to restructure the Corps as an arm of the fleet by issuing General Order 241 in December 1933; the Fleet Marine Force was born. Russell then canceled the 1933–34 academic term at Marine Corps schools in Quantico so the faculty and students could write the Tentative Manual for Landing Operations.19

Enough proponents of small wars doctrine existed, however, to complete a draft of the Small Wars Manual in 1935. The text reflected the entire corpus of Marine knowledge on counterinsurgency and contingency operations. It long stood as the single most comprehensive text devoted solely to small wars in the U.S. military.

But courses on the subject never took up more than 15 percent of students’ instruction at Quantico.20 While the Fleet Marine Force conducted fleet landing exercises throughout the late 1930s, a small group of Marines, including Utley and Harrington, worked on and published a revised version in 1940—on the eve of U.S. entry into another world war.

Small Wars Then, Small Wars Again

The United States’ fortunes spent nation-building and fighting insurgencies in the early 20th century had mixed results.21 Soldiers and Marines oversaw the construction of thousands of miles of roads and telephone lines and many airfields, hospitals, clinics, and schools. They organized and trained indigenous security forces and provided security for elections. More than 4,000 U.S. troops died fighting in the Philippines, while 47 Marines died in Nicaragua and 26 were killed in Hispaniola.22 Many thousands more Filipinos, Haitians, Dominicans, and Nicaraguans died as a direct result of the occupations.

Although the Caribbean interventions succeeded in keeping European competitors out of the region (a major strategic goal), they also left a troubled legacy for the United States. Haiti would fall victim once again to internal political strife and suffer through a series of brutal dictatorships.

In the Dominican Republic, Marine-trained Rafael Trujillo used the Guardia Nacional in 1930 to seize and keep power until 1961. One historian has argued that the U.S. occupation of Cuba, in which Marines played a significant role, helped push Cubans toward communism and an alliance with the Soviet Union that precipitated the Bay of Pigs fiasco in 1961 and the Cuban Missile Crisis the following year.23

These wars’ immediate impact on the Corps was ambiguous as well. Most Marines embraced amphibious operations as the Corps’ future over counterinsurgencies and contingency missions. Promotion boards in the 1920s favored officers who fought in France over those who had not.24 Officers most associated with the “Banana Wars”—Waller, Butler, Pendleton—never became commandants. After retirement, Butler became a staunch antiwar advocate and authored War Is a Racket, a dark critique of U.S. foreign policy.25

On the other hand, the valuable experience in jungle fighting and close air support Marines gained would prove invaluable in many Pacific campaigns. Despite the Corps’ penchant for amphibious assault missions and training, once the transports left the beach the Tentative Manual for Landing Operations was of little use. Marines relied on small war veterans like Merritt Edson, “Chesty” Puller, and Hermann Hanneken, all of whom drew on their experiences in Nicaragua and Hispaniola to lead them successfully in vicious jungle fighting in the Pacific.26

For the past 70 years, counterinsurgency and contingency missions have dominated the Corps’ history.27 The Vietnam War, the numerous contingency operations of the 1980s and ’90s, and the two decades–long war on terrorism bear this out. Marines and soldiers have relearned over and over how difficult and unpopular these wars are. Once again, the services are moving away from counterinsurgency operations. But if the United States remains a world power, Marines will have to be ready for small wars missions in the future.

1. Jackson Lears, Rebirth of a Nation: The Making of Modern America, 1877–1920 (New York: Harper Collins, 2009), 279; Lester D. Langley, The Banana Wars: United States Intervention in the Caribbean, 1898–1934 (Wilmington, DE: Scholarly Resources Inc, 2002), xv.

2. Allan R. Millett, Peter Maslowski, and William B. Feis, For the Common Defense: A Military History of the United States from 1607 to 2012, 3d ed., (New York: Free Press, 2012), 282–83.

3. Andrew J. Birtle, U.S. Army Counterinsurgency and Contingency Operations Doctrine, 1860–1941 (Washington, DC: Center of Military History, 2009), 108.

4. Edward H. Crosby, “The Military Idea of Manliness,” The Independent, April 1901, 833.

5. Birtle, Counterinsurgency Doctrine, 181–82.

6. Annual Report of the Secretary of the Navy, 1914 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1915), 462.

7. Gordon L. Rottman, U.S. Marine Corps World War II Order of Battle: Ground and Air Units in the Pacific War, 1939–1945 (West Port CT: Greenwood Press, 2002), 15.

8. Hans Schmidt, The United States Occupation of Haiti, 1915–1934 (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1995), 64–65; Mary A. Renda, Taking Haiti: Military Occupation and the Culture of U.S. Imperialism, 1915–1940 (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2001), 29–31.

9. Allan R. Millett, Semper Fidelis: The History of the United States Marine Corps (New York: Free Press, 1991), 192. Bruce J. Calder, The Impact of Intervention: The Dominican Republic During the U.S. Occupation of 1916–1924 (Princeton, NJ: Markus Wiener Publishers, 2006), 8–10; Keith B. Bickel, Mars Learning: The Marine Corps Development of Small Wars Doctrine, 1915–1940 (Boulder CO: Westview Press, 2001), 58–59.

10. Quoted report from an unnamed brigade commander in Brigadier-General George Barnett to the Secretary of Navy, Report on Affair in the Republic of Haiti, June 1915 to June 30, 1920, U.S. Marine Corps History Division (USMC HD), Quantico, VA.

11. Major Thomas C. Turner, “Report of investigation of certain irregularities alleged to have been committed by officers and enlisted men in the Republic of Haiti,” 3 November 1919, Haitian Geographic Files, USMC HD.

12. Bruce Calder, “Caudillos and Gavilleros versus the United States Marines: Guerrilla Insurgency During the Dominican Intervention, 1916–1924,” The Hispanic American Historical Review 58, no. 4 (November 1978): 656; see also Millett, Semper Fidelis, 196.

13. Calder, The Impact of Intervention, 149; Hearings before a Select Committee of Haiti and Santo Domingo, 2 vols., 67th Cong., 1st and 2d sess., 1922, 1119; Langley, The Banana Wars, 146.

14. Charles F. Merkel to Russell W. Duck, 2 October 1918, Charles Merkel Personnel File, National Personnel Records Center, St. Louis, MO; Mark R. Folse, “The Tiger of Seibo: Charles Merkel, George C. Thorpe, and the Dark Side of Marine Corps History,” Marine Corps History 1, no. 2 (Winter 2016): 4–18.

15. Breanne Robertson, “Rebellion, Repression, and Reform: U.S. Marines in the Dominican Republic,” Marine Corps History 2, no. 1 (Summer 2016): 47–50.

16. Col L. W. T. Waller to Col S. D. Butler, 13 July 1916, Butler Papers, Marine Corps Archives (MCA), Quantico, VA; Millett, Semper Fidelis, 187.

17. BGen Edwin Howard Simmons, USMC (Ret.), The United States Marines: A History (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2002), 112–14.

18. Jeffrey W. Meiser, Power and Restraint: The Rise of the United States 1898–1941 (Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, 2015), 195.

19. Bickel, Mars Learning, 211–13; Millett, Semper Fidelis, 330–32.

20. Bickel, Mars Learning, 222.

21. Alan McPherson, The Invaded: How Latin Americans and Their Allies Fought and Ended U.S. Occupations (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014), 262.

22. For Philippine numbers, see Timothy K. Deady, “Lessons from a Successful Counterinsurgency: The Philippines, 1899–1902,” Parameters 35, no. 1 (June 2005): 53–68. For Hispaniola and Nicaragua, see Simmons, The United States Marines, 117; Max Boot, Savage Wars of Peace: Small Wars and the Rise of American Power (New York: Basic Books, 2003), 180.

23. Aaron O’Connell, “Defending Imperial Interests in Asia and the Caribbean, 1898–1941,” in America, Sea Power, and the World, James Bradford, ed. (Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell and Sons, 2016), 161.

24. Oral history transcript, Brigadier General Victor F. Bleasdale, interviewed by Benis M. Frank, 4 December 1979 (Washington, DC: History and Museums Division, Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps, 1984), 160; Millett, Semper Fidelis, 323.

25. Smedley D. Butler, War Is a Racket, Adam Parfrey, ed. (Los Angeles: Feral House, 2003), 24.

26. Bickel, Mars Learning, 250.

27. Jeannie L. Johnson, The Marines Counterinsurgency and Strategic Culture: Lessons Learned and Lost in America’s Wars (Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, 2018) 6–7.