The anatomy of a gunstock on a Ruger 10/22 semi-automatic rifle with Fajen thumbhole silhouette stock. 1) butt, 2) forend, 3) comb, 4) heel, 5) toe, 6) grip, 7) thumbhole

A gunstock or often simply stock, the back portion of which is also known as a shoulder stock, a buttstock or simply a butt, is a part of a long gun that provides structural support, to which the barrel, action, and firing mechanism are attached. The stock also provides a means for the shooter to firmly brace the gun and easily aim with stability by being held against the user’s shoulder when shooting the gun, and helps to counter muzzle rise by transmitting recoil straight into the shooter’s body.[1]

The tiller of a crossbow is functionally the equivalent of the stock on a gun.[2]

History and etymology[edit]

An early hand cannon, or gonne, supported by a simple stock

The term stock in reference to firearms dates to 1571 is derived from the Germanic word Stock, meaning tree trunk, referring to the wooden nature of the gunstock.[3]

Early hand cannons used a simple stick fitted into a socket in the breech end to provide a handle. The modern gunstock shape began to evolve with the introduction of the arquebus, a matchlock with a longer barrel and an actual lock mechanism, unlike the hand-applied match of the hand cannon. Firing a hand cannon requires careful application of the match while simultaneously aiming; the use of a matchlock handles the application of the slow match, freeing up a hand for support. With both hands available to aim, the arquebus could be braced with the shoulder, giving rise to the basic gunstock shape that has survived for over 500 years.[4] This greatly improved the accuracy of the arquebus, to a level that would not be surpassed until the advent of rifled barrels.[5]

Ironically, the stocks of muskets introduced during the European colonization of the Americas were repurposed as hand-to-hand war clubs[6][7] by Native Americans and First Nations when fragile accessories were damaged or scarce ammunition exhausted. Techniques for gunstock hand weapons are being revived by martial arts such as Okichitaw.

Anatomy of a gunstock[edit]

A gunstock is broadly divided into two parts (see above), with the boundary roughly at where the trigger is. The rear portion is the butt (1), and front portion is the fore-end (2). The fore-end (or forestock, forearm) affixes and supports the receiver, and relays the recoil impulse from the barrel via a recoil lug. The butt (or buttstock) is braced against the shooter’s shoulder for stability and also interacts with the trigger hand, and is further divided into the comb (3), heel (4), toe (5), and grip (6). The stock pictured above has a thumbhole (7) style grip,[8] which allows a more ergonomic vertical hold for the user’s hand.

In some modern firearm designs, the lower receiver and handguard replace the fore-end stock, leaving only the butt portion as the recognizable “stock”, even though they serve the same function as the traditional fore-end.

Styles and features of stocks[edit]

The most basic categorization of stock types is into one-piece and two-piece stocks. In a one-piece stock, the butt and fore-end are a continuous monolithic piece, such as that commonly found on conventional bolt-action rifles. Two-piece stocks use separate pieces for the butt and fore-end, such as that commonly found on break-action and lever-action firearms. Traditionally, two-piece stocks were easier to make, since finding a quality wood blank suitable for a long one-piece stock is harder than finding short blanks for a two-piece stock.[8]

In one-piece rifle stocks, the butt also varies in styles between the “European” type, which has a drop at the heel to favor quick shooting using iron sights; and “American” type, which the heel remains horizontal from the grip to favor more precision-oriented shooting using telescopic sights. There are also in-between designs (such as the Weatherby Mark V) with a “halfway” heel drop where the front half of the buttstock stays leveled.

Collapsable or folding stocks are often seen on military carbines, SMG/PDWs, their civilian-derived versions and some machine pistols. A collapsible (or telescoping) stock makes the weapon shorter and more compact for storage, carrying and concealment, and can be deployed just before shooting for better control. A butt hook, which is an attachment to the butt of the gun that is put under the shooter’s arm to prevent the rifle from pivoting forward from the weight of the barrel is sometimes used in competitive rifle shooting.[9] These stocks are also used on combat shotguns like the Franchi SPAS-12 to allow the stock to collapse when not in use.[10]

Different styles of gunstock grips

The grip is at the front portion of the butt that connects with the fore-end, and is held by the shooter’s trigger hand during firing. The back surface of butt front near the grip is called the tang. Many grips have roughened textures or even finger grooves engraved into the sides to increase the firmness of the shooter’s hold. Some grips have a thumb rest (or groove) carved near the tang to give a more ergonomic hold for the trigger finger.

The grip varies widely in styles. A straight grip stock (A) proceeds smoothly from toe to the trigger, giving a nearly horizontal holding angle for the trigger hand, while a full pistol grip stock (E) contains a separate stand-out grip piece, providing a nearly vertical angle for the trigger hand for maximal ergonomics, and is commonly found on modern military rifles such as the ubiquitous AK-47 and M16/M4 families of assault rifles. In between the two extremes, the semi-grip stock (B) is perhaps the most common sporting rifle stock, with a steeper angle cut into the stock to provide a more diagonal angle for the trigger hand. Modern target-style stocks have generally moved towards a fuller, more vertical grip, though built into the stock rather than made as a separate piece. Anschütz grip stocks (C), for example, use a nearly vertical grip, and many thumbhole grip stocks (D) are similar to pistol grips in shape.

Variations in gunstock combs

The comb is another area of wide variation. Since the comb must support the shooter’s cheek at a height that steadily aligns the aiming eye with the weapon’s sights, higher sights such as telescopic sights require higher combs.

The simplest form is a straight comb (A), which is the default form seen in all traditional rifles with iron sights. The Monte Carlo comb (B) is commonly found on stocks designed for use with scopes, and features an elevated comb to lift the cheek higher, while keeping the heel of the stock low. If the elevated comb is of a rounded dome shape, it is often called a hogback comb. A cheekpiece (C) is a raised section protruding from the side of the stock, which provides a more conformed support for the shooter’s cheek. There is some confusion between these terms, as the features are often combined, with the raised rollover cheekpiece (D) extending across the top of the stock to form essentially an exaggeratedly wide and high Monte Carlo comb.[8][11][12]

Some modern buttstocks have a movable comb piece called a cheek rest or cheek rise, which offers adjustable comb height that tailors to the shooter’s ergonomic preference.

Fore-end[edit]

The fore-ends tend to vary both in thickness, from the splinter fore-ends common on British side-by-side shotguns to the wide, flat bottomed beavertail fore-ends found on benchrest shooting guns, and in length, from the short AK-47 style to the long Mannlicher stock that runs all the way to the muzzle. Most common on sporting firearms is the half-stock, which extends roughly half the length of the barrel.[8][13]

Stock measurements[edit]

Stock measurements are important regarding target rifle stocks if competing in IBS or NBRSA registered matches. The target rifle stocks must meet certain dimensional and configuration criteria according to the class of competition engaged in. Stock dimensioning is especially important with shotguns, where the typical front-bead-only sight requires a consistent positioning of the shooter’s eye over the center of the barrel for good accuracy. When having a stock custom built or bent to fit, there are a number of measurements that are important.[8][14]

- Sight line, a datum line along the line of visual aim, extending axially to all points necessary for shotgun stock reference measurements.

- Length of pull, the length measured from the back end of the butt to the trigger. Many newer stock designs have an adjustable length of pull. Other relevant length measurements affected by the length of pull include length to sight (LTS) and length to handstop (LTH).[15]

- Drop at heel, the distance from the sightline to the heel of the butt. Sometimes also called the height of the buttpad or buttplate height.

- Drop at comb, the distance from the sightline to the comb. Sometimes also called the height of the cheek rest or cheekpiece height.

- Cast is sometimes also called offset.[15]

- Cast off, the distance from the center of the butt to the Sight line, to the right side as seen from the rear. Often used by those shooting from the right shoulder.

- Cast on, the distance from the center of the butt to the Sight line, to the left side as seen from the rear. Often used by those shooting from the left shoulder.

- Pitch, the vertical angle of the butt of the stock, determined by a straight line from heel to toe, referenced perpendicular to the Sight line.

- Cant, the angle of the butt of the stock, rotated around an axis parallel to the bore line, referenced to zero degrees if pointing vertical to the ground.[15]

- Bore line, A datum line concentric with the barrel bore and extending axially to all points necessary for rifle stock reference measurements.

- Recoil arm, the vertical distance between the bore axis and the contact point of the stock against the shoulder where the recoil acts. If the recoil line corresponds to the bore line, the firearm can recoil straight backwards and minimize muzzle rise.[16]

- Corporal line, the bottom edge of the butt of the stock, or as determined by a straight line from grip to toe.

- Corporal angle, the angle of the corporal line referenced to the bore line at the corporal intercept point.

- Corporal intercept point, the point on the bore line forward of the bolt face where (if) the corporal line intercepts the bore line.

- Handguard rotation, only found on firearms where the handguard can be rotated.[15]

Accuracy considerations[edit]

M16A1 cutaway rifle (top) and M16A2 (below) with a “straight-line” stock configuration

In addition to ergonomic issues, the stock can also have a significant impact on the accuracy of the rifle. The key factors are:

- A secure fit between the stock and action, so that the rifle does not shift under recoil

- A stable material, that does not suffer from changes in shape with temperature, humidity, or other environmental conditions to a degree that could adversely impact accuracy

A well designed and well built wooden stock can provide the secure, stable base needed for an accurate rifle, but the properties of wood make it more difficult than more stable synthetic materials. Wood is still a top choice for aesthetic reasons, however, and solutions such as bedding provide the stability of a synthetic with the aesthetics of wood.[17][18]

Burst or automatic shoulder fired small arms can incorporate the “straight-line” recoil configuration. This layout places both the center of gravity and the position of the shoulder stock nearly in line with the longitudinal axis of the barrel bore, a feature increasing controllability during burst or automatic fire.[16]

Adjustability[edit]

Traditional gunstocks have a permanently-shaped buttstock that is fixed in length of pull and comb height, and cannot tailor to the anatomical variation between different users. If the user wants a more comfortable head position to achieve better natural point of aim, then an additional cheek pad (which add to the comb height) or buttplate (which add to the length of pull) need to be installed. These improvisations might not be ideal as they might still not achieve optimal fitting to a person’s ergonomics.

Modern manufacturing and gunsmithing techniques can produce gunstocks with variable comb heights and buttplate positions. This can be achieved either by having interchangeable modules or using spacer blocks, which can increase the vertical and horizontal thickness. Alternatively, the buttstock can be built with a movable comb (known as a cheek riser) and/or buttplate, which use one or more guide rails to control position changes. These moveable parts can be adjusted using a leadscrew (usually turned with a thumb wheel), or have them slide freely along the guide rails and then fastened to desirable positions with set screws or thumbscrews. Some more complex designs also allow horizontal shifting and tilting of the cheek riser, as well as vertical shifting and slanting of the buttplate.

Construction[edit]

Traditionally, stocks are made from wood, generally a durable hardwood such as walnut. A growing option is the laminated wood stock, consisting of many thin layers of wood bonded together at high pressures with epoxy, resulting in a dense, stable composite.[18][17]

Regardless of the material actually employed, the general term “furniture” is often applied to gunstocks by curators, researchers and other firearm experts.

Folding, collapsible, or removable stocks tend to be made from a mix of steel or alloy for strength and locking mechanisms, and wood or plastics for shape. Stocks for bullpup rifles must take into account the dimensions of the rifle’s action, as well as ergonomic issues such as ejection.

Wood stocks[edit]

Gun stock construction on a lathe from the 1850s (photo circa 2015)

While walnut is the favored gunstock wood, many other woods are used, including maple, myrtle, birch, and mesquite. In making stocks from solid wood, one must take into account the natural properties and variability of woods. The grain of the wood determines the strength, and the grain should flow through the wrist of the stock and out the toe; having the grain perpendicular to these areas weakens the stock considerably.[17]

In addition to the type of wood, how it is treated can have a significant impact on its properties. Wood for gunstocks should be slowly dried, to prevent grain collapse and splitting, and also to preserve the natural color of the wood; custom stockmakers will buy blanks that have been dried two to three years and then dry it for several additional years before working it into a stock. Careful selection can yield distinctive and attractive features, such as crotch figure, feathering, fiddleback, and burl, which can significantly add to the desirability of a stock. While a basic, straight grained blank suitable for a utilitarian stock might sell for US$20, an exhibition grade blank with superb figure could price in the range of US$2000. Blanks for one piece stocks are more expensive than blanks for two piece stocks, due to the greater difficulty in finding the longer blanks with desirable figure. Two piece stocks are ideally made from a single blank, so that the wood in both parts shows similar color and figure.[19]

Laminated wood[edit]

Laminated wood consists of two or more layers of wood, impregnated with glue and attached permanently to each other. The combination of the two pieces of wood, if laid out correctly, results in the separate pieces moderating the effects of changes in temperature and humidity. Modern laminates consist of 1/16 inch (1.6 mm) thick sheets of wood, usually birch, which are impregnated with epoxy, laid with alternating grain directions, and cured at high temperatures and pressures. The resulting composite material is far stronger than the original wood, free from internal defects, and nearly immune to warping from heat or moisture. Typically, each layer of the laminate is dyed before laminating, often with alternating colors, which provides a pattern similar to wood grain when cut into shape, and with bright, contrasting colors, the results can be very striking. The disadvantage of laminate stocks is density, with laminates weighing about 4 to 5 ounces (110 to 140 g) more than walnut for a typical stock.[18]

While wood laminates have been available for many years on the custom market (and, in subdued form, in some military rifles), in 1987 Rutland Plywood, a maker of wood laminates, convinced Sturm, Ruger, Savage Arms, and U.S. Repeating Arms Company (Winchester) to display some laminate stocks on their rifles in a green, brown and black pattern (often called camo). The response was overwhelming, and that marked the beginning of laminated stocks on production rifles.[18]

Injection molded synthetic[edit]

While setup costs are high, once ready to produce, injection molding produces stocks for less than the cost of the cheapest wood stocks. Every stock is virtually identical in dimension, and requires no bedding, inletting, or finishing. The downsides are a lack of rigidity and thermal stability, which are side effects of the thermoplastic materials used for injection molding.[18]

Hand-laid composite stocks[edit]

A hand-laid composite stock is composed out of materials such as fiberglass, Kevlar, graphite cloth, or some combination, saturated in an appropriate binder, placed into a mold to set, or solidify. The resulting stock is stronger and more stable than an injection-molded stock. It can also be as little as half the weight of an injection-molded stock. Inletting and bedding can be accomplished by molding in as part of the manufacturing process, machining in the inletting after the stock is finished, molding directly to the action as a separate process, or molding a machined metal component in place during manufacture. Finish is provided by a layer of gel coat applied to the mold before the cloth is laid up.[18]

Metallic[edit]

Some high production firearms (such as the PPS-43, MP-40, and the Zastava M70B) make use of metal frames in order to have a thin but strong stock that can be folded away to make the weapon more compact. However, even a skeletonized steel stock is often heavier than the equivalent solid wooden stock. Consequentially, less cost-sensitive designs like the FN Minimi make use of lighter-than-steel materials such as aluminium alloy or titanium. A few designs, like the Accuracy International Arctic Warfare, use a metallic chassis which securely beds the functional components of the firearm, with non-structural polymer panels attached externally like a shell for ergonomics and aesthetics.

Non-fixed stock[edit]

Telescoping stock[edit]

M4 carbine with a telescoping stock

A telescoping stock, also known as a collapsible or retractable stock, is a buttstock that can shorten by telescoping into itself, usually by sliding along guide rails or an M4-style buffer tube. They are useful in allowing a rifle, submachine gun, shotgun or even light machine gun to be stored or maneuvered in tight spaces where it would otherwise have trouble fitting. The user can either slide in (“collapse”) the buttstock to make the weapon more portable and concealable, or extend (“deploy”) it for bracing. Some telescoping stocks can shorten to more than one length of pull settings, allowing the stock to have some ergonomic customization for different users.

Folding stock[edit]

An AK-103 with its stock folded

Some buttstocks can have a hinged attachment to the receiver and can be folded forward to shorten the overall length of the gun. The hinge usually has a locking mechanism to prevent accidental or unwanted movements of the buttstock. When stability is not needed, the gun can be folded down to save space, be concealed, or held with one hand or nearer to the core; when stable aim is needed, the buttstock can be quickly extended and held to the shoulder.

Most folding stocks bend left or right depending on factory design or user preferences. Some are however designed to bend up and down, and usually made of a minimalistic “skeletonized” frame to fit over and envelop the receiver. Some compact weapons (e.g. machine pistols) have foldable buttstocks with more than one articulations to allow even more shortening.

Bump stock[edit]

A bump stock allows semi-automatic firearms to shoot at a faster rate of fire that somewhat mimics fully automatic fire.

A bump fire stock or bump stock utilizes the recoil of a semi-automatic rifle to facilitate a faster rate of fire without requiring any modification of internal mechanisms to convert the firearm to an automatic firearm.

The term “bump fire” was originally an improvised technique to shoot an AR-15 faster by having the shooter applying a non-rigid forward push on the receiver (by gripping the handguard or via a foregrip) and having a loose hold on the pistol grip. When the gun shoots, the recoil shifts the receiver backwards, moving the trigger conversely forward (from the receiver’s frame of reference) and relaxes the pulling force on the trigger, allowing it to reset. When the shooter’s forward push overcomes the recoil momentum and shifts the receiver back towards the front, the trigger is “bumped” against the shooter’s finger and get depressed again, firing off another round, which produces another recoil that repeats the above process. This allows a cycling rate of firing much faster than what the shooter’s own finger can typically achieve, but is usually inaccurate due to the shooter often have to fire from the hip to still hold the gun firmly.

A bump stock replaces the manual forward push with a spring mechanism at the interface between the receiver and the pistol grip/buttstock. The user only have to simply hold the trigger back against the grip, and the spring-assisted forward push will itself work against the recoil to cycle the shooting. This allows an increased rate of fire that can reach several hundred rounds per minute, and is far more consistent in performance compared to the manual bump fire.

For handguns[edit]

The Luger Artillery Pistol with its wooden holster attached

The CZ Škorpion with its folding wire stock extended.

Many handguns also support the use of shoulder stocks to handle recoil. An example is the Luger P08 “Artillery Pistol”, which has a wooden factory holster that can be attached to the pistol grip and used as a buttstock. Some aftermarket manufacturers also make accessories for popular semi-automatic pistols such as Glocks, including grip modules that has built-on folding stocks, or even “conversion kit” that allows the pistol to be mounted into a carbine-shaped enclosure with a shoulder stock.

Machine pistols such as the MAC-10, Micro-Uzi and Škorpion vz. 61 often use a folding skeleton stock, that can be extended and braced during engagements to provide auto-fire stability.

Pistol brace[edit]

A pistol stabilizing brace (PSB) or arm brace is a device similar in shape to a buttstock, but is meant to be in contact with or wrap around the shooter’s forearm like a wrist brace or splint, instead of being pressed against the shoulder. It is mainly designed for pistols with carbine-style receivers (e.g. “AR pistols” and PC Charger), which are stockless out-of-factory to avoid being legally classified as short-barreled rifles, as an alternative measure of countering recoil and muzzle rise with one-handed shooting. The brace can be mounted to the pistol via an M4-style buffer tube, or via a Picatinny rail interface.

Even though the bulkier end of a brace can still be leaned against the shoulder like a shoulder stock, doing so would invite the same legal complications as shoulder stocks do.[20] On December 18, 2020, the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives filed a notice to the Federal Register titled Objective Factors for Classifying Weapons with “Braces”, proposing a series of criteria used to evaluate whether pistols with attached stabilizing braces are firearms that should be regulated by the National Firearms Act,[21] but withdrew the notice five days later.[22]

Legal issues[edit]

In some jurisdictions, the nature of the stock may change the legal status of the firearm. Examples of this are:

- Adding a shoulder stock on a firearm with a barrel shorter than 16 inches (41 cm) changes it into a short-barreled rifle (SBR) under the United States National Firearms Act.

- Folding stocks, or stocks with separate pistol grips, are regarded as assault weapon features and banned in some U.S. states and municipalities.

- In the United States, fitting a bump stock to a semi-automatic firearm causes it to be classified as a machine gun by the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives, meaning they are effectively banned on the federal level. They are also banned in Canada and the United Kingdom.

Gallery[edit]

-

-

-

-

AK-47 with a three piece stock consisting of butt, grip and fore-end

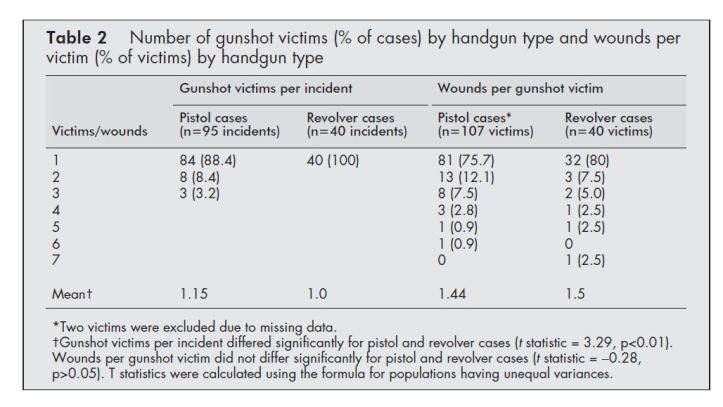

So, basically one more shot per incident on average for semi-auto pistols than revolvers. Not exactly a hail of gunfire in either case, and certainly not a major difference between the two gun action types.

So, basically one more shot per incident on average for semi-auto pistols than revolvers. Not exactly a hail of gunfire in either case, and certainly not a major difference between the two gun action types.